Advances in Spectral Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution, Mass Loss and Variability of Low and Intermediate-Mass Stars What Are Low and Intermediate Mass Stars?

Evolution, Mass Loss and Variability of Low and Intermediate-Mass Stars What are low and intermediate mass stars? Defined by properties of late stellar evolutionary stages Intermediate mass stars: ~1.9 < M/Msun < ~7 Develop electron-degenerate cores after core helium burning and ascending the red giant branch for the second time i.e. on the Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB). AGB Low mass stars: M/Msun < ~1.9 Develop electron-degenerate cores on leaving RGB the main-sequence and ascending the red giant branch for the first time i.e. on the Red Giant Branch (RGB). Maeder & Meynet 1989 Stages in the evolution of low and intermediate-mass stars These spikes are real The AGB Surface enrichment Pulsation Mass loss The RGB Surface enrichment RGB Pulsation Mass loss About 108 years spent here Most time spent on the main-sequence burning H in the core (~1010 years) Low mass stars: M < ~1.9 Msun Intermediate mass stars: Wood, P. R.,2007, ASP Conference Series, 374, 47 ~1.9 < M/Msun < ~7 Stellar evolution and surface enrichment The Red giant Branch (RGB) zHydrogen burns in a shell around an electron-degenerate He core, star evolves to higher luminosity. zFirst dredge-up occurs: The convection in the envelope moves in when the stars is near the bottom of the RGB and "dredges up" material that has been through partial hydrogen burning by the CNO cycle and pp chains. From John Lattanzio But there's more: extra-mixing What's the evidence? Various abundances and isotopic ratios vary continuously up the RGB. This is not predicted by a single first dredge-up alone. -

Spectroscopic Orbits of Three Dwarf Barium Stars

SPECTROSCOPIC ORBITS OF THREE DWARF BARIUM STARS By P. L. North1, A. Jorissen2, A. Escorza2;3, B. Miszalski4;5, and J. Mikoajewska6 1Institute of Physics, Laboratory of Astrophysics, Ecole Polytechnique F´ed´erale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland 2Institut d'Astronomie et d'Astrophysique, Universit´eLibre de Bruxelles, Belgium 3Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, KU Leuven, Belgium 4South African Astronomical Observatory 5Southern African Large Telescope Foundation 6N. Copernicus Astronomical Center, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Barium stars are thought to result from binary evolution in systems wide enough to allow the more massive component to reach the asymptotic giant branch and eventually become a CO white dwarf. While Ba stars were initially known only among giant or subgiant stars, some were subsequently discovered also on the main sequence (and known as dwarf Ba stars). We provide here the orbital parameters of three dwarf Ba stars, completing the sample of 27 orbits published recently by Escorza et al. with these three southern targets. We show that these new orbital parameters are consistent with those of other dwarf Ba stars. Introduction Barium stars are not evolved enough to synthesize in their interiors and dredge up to their surface the s-process elements (including Ba) that are very abundant in their atmospheres. On the other hand, we have convincing statistical indications that they all belong to SB1-type binary systems [1] [2], and UV arXiv:2001.11319v1 [astro-ph.SR] 30 Jan 2020 observations have revealed the white -

The Deaths of Stars

The Deaths of Stars 1 Guiding Questions 1. What kinds of nuclear reactions occur within a star like the Sun as it ages? 2. Where did the carbon atoms in our bodies come from? 3. What is a planetary nebula, and what does it have to do with planets? 4. What is a white dwarf star? 5. Why do high-mass stars go through more evolutionary stages than low-mass stars? 6. What happens within a high-mass star to turn it into a supernova? 7. Why was SN 1987A an unusual supernova? 8. What was learned by detecting neutrinos from SN 1987A? 9. How can a white dwarf star give rise to a type of supernova? 10.What remains after a supernova explosion? 2 Pathways of Stellar Evolution GOOD TO KNOW 3 Low-mass stars go through two distinct red-giant stages • A low-mass star becomes – a red giant when shell hydrogen fusion begins – a horizontal-branch star when core helium fusion begins – an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star when the helium in the core is exhausted and shell helium fusion begins 4 5 6 7 Bringing the products of nuclear fusion to a giant star’s surface • As a low-mass star ages, convection occurs over a larger portion of its volume • This takes heavy elements formed in the star’s interior and distributes them throughout the star 8 9 Low-mass stars die by gently ejecting their outer layers, creating planetary nebulae • Helium shell flashes in an old, low-mass star produce thermal pulses during which more than half the star’s mass may be ejected into space • This exposes the hot carbon-oxygen core of the star • Ultraviolet radiation from the exposed -

A Nn U a L Re P O

2008 A NORDIC OPTICAL NN TELESCOPE U Galaxy clusters acting as gravitational lenses. A L RE P O R T NORDIC OPTICAL TELESCOPE The Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) is a modern 2.5-m telescope located at the Spanish Observa- torio del Roque de los Muchachos on the island of La Palma, Canarias, Spain. It is operated for the benefit of Nordic astronomy by theN ordic Optical Telescope Scientific Asso ciation (NOTSA), estab- lished by the national Research Councils of Den- mark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, and the Uni- versity of Iceland. The chief governing body of NOTSA is the Council, which sets overall policy, approves the annual bud- gets and accounts, and appoints the Director and Astronomer-in-Charge. A Scienti fic and Technical Committee (STC) advises the Council on scientific and technical policy. An Observing Programmes Committee (OPC) of independent experts, appointed by the Council, performs peer review and scientific ranking of the observing proposals submitted. Based on the rank- Front cover: A mosaic of galaxy clusters ing by the OPC, the Director prepares the actual showing strong gravitational lensing and observing schedule. giant arcs discovered with the NOT (see p. 5). Composite images in blue and red light from the NOT, Gemini, and Subaru The Director has overall responsibility for the telescopes. Photo: H. Dahle, Oslo. operation of NOTSA, including staffing, financial matters, external relations, and long-term plan- ning. The staff on La Palma is led by the Astrono- mer-in-Charge, who has authority to deal with all matters related to the daily operation of NOT. -

U Antliae — a Dying Carbon Star

THE BIGGEST, BADDEST, COOLEST STARS ASP Conference Series, Vol. 412, c 2009 Donald G. Luttermoser, Beverly J. Smith, and Robert E. Stencel, eds. U Antliae — A Dying Carbon Star William P. Bidelman,1 Charles R. Cowley,2 and Donald G. Luttermoser3 Abstract. U Antliae is one of the brightest carbon stars in the southern sky. It is classified as an N0 carbon star and an Lb irregular variable. This star has a very unique spectrum and is thought to be in a transition stage from an asymptotic giant branch star to a planetary nebula. This paper discusses possi- ble atomic and molecular line identifications for features seen in high-dispersion spectra of this star at wavelengths from 4975 A˚ through 8780 A.˚ 1. Introduction U Antliae (U Ant = HR 4153 = HD 91793) is classified as an N0 carbon star with a visual magnitude of 5.38 and B−V of +2.88 (Hoffleit 1982). It also is classified as an Lb irregular variable with small scale light variations. Scattered light optical images for U Ant have been made and these observations are consistent the existence of a geometrically thin (∼3 arcsec) spherically symmetric shell of radius ∼43 arcsec. The size of this shell agrees very well with that of the detached shell seen in CO radio line emission. These observations also show the presence of at least one, possibly two, shells inside the 43 arcsec shell (Gonz´alez Delgado et al. 2001). In this paper, absorption lines in the optical spectrum of U Ant are tentatively identified for this bright cool carbon star. -

Stellar Spectral Classification of Previously Unclassified Stars Gsc 4461-698 and Gsc 4466-870" (2012)

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2012 Stellar Spectral Classification Of Previously Unclassified tS ars Gsc 4461-698 And Gsc 4466-870 Darren Moser Grau Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Grau, Darren Moser, "Stellar Spectral Classification Of Previously Unclassified Stars Gsc 4461-698 And Gsc 4466-870" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 1350. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STELLAR SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION OF PREVIOUSLY UNCLASSIFIED STARS GSC 4461-698 AND GSC 4466-870 By Darren Moser Grau Bachelor of Arts, Eastern University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2012 Copyright 2012 Darren M. Grau ii This thesis, submitted by Darren M. Grau in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done and is hereby approved. _____________________________________ Dr. Paul Hardersen _____________________________________ Dr. Ronald Fevig _____________________________________ Dr. Timothy Young This thesis is being submitted by the appointed advisory committee as having met all of the requirements of the Graduate School at the University of North Dakota and is hereby approved. -

Carbon Stars T. Lloyd Evans

J. Astrophys. Astr. (2010) 31, 177–211 Carbon Stars T. Lloyd Evans SUPA, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St. Andrews, North Haugh, St. Andrews, Fife KY16 9SS, UK. e-mail: [email protected] Received 2010 July 19; accepted 2010 October 18 Abstract. In this paper, the present state of knowledge of the carbon stars is discussed. Particular attention is given to issues of classification, evolution, variability, populations in our own and other galaxies, and circumstellar material. Key words. Stars: carbon—stars: evolution—stars: circumstellar matter —galaxies: magellanic clouds. 1. Introduction Carbon stars have been reviewed on several previous occasions, most recently by Wallerstein & Knapp (1998). A conference devoted to this topic was held in 1996 (Wing 2000) and two meetings on AGB stars (Le Bertre et al. 1999; Kerschbaum et al. 2007) also contain much on carbon stars. This review emphasizes develop- ments since 1997, while paying particular attention to connections with earlier work and to some of the important sources of concepts. Recent and ongoing develop- ments include surveys for carbon stars in more of the galaxies of the local group and detailed spectroscopy and infrared photometry for many of them, as well as general surveys such as 2MASS, AKARI and the Sirius near infrared survey of the Magel- lanic Clouds and several dwarf galaxies, the Spitzer-SAGE mid-infrared survey of the Magellanic Clouds and the current Herschel infrared satellite project. Detailed studies of relatively bright galactic examples continue to be made by high-resolution spectroscopy, concentrating on abundance determinations using the red spectral region, and infrared and radio observations which give information on the history of mass loss. -

Stellar Evolution

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 19 www.accessscience.com Stellar evolution Contributed by: James B. Kaler Publication year: 2014 The large-scale, systematic, and irreversible changes over time of the structure and composition of a star. Types of stars Dozens of different types of stars populate the Milky Way Galaxy. The most common are main-sequence dwarfs like the Sun that fuse hydrogen into helium within their cores (the core of the Sun occupies about half its mass). Dwarfs run the full gamut of stellar masses, from perhaps as much as 200 solar masses (200 M,⊙) down to the minimum of 0.075 solar mass (beneath which the full proton-proton chain does not operate). They occupy the spectral sequence from class O (maximum effective temperature nearly 50,000 K or 90,000◦F, maximum luminosity 5 × 10,6 solar), through classes B, A, F, G, K, and M, to the new class L (2400 K or 3860◦F and under, typical luminosity below 10,−4 solar). Within the main sequence, they break into two broad groups, those under 1.3 solar masses (class F5), whose luminosities derive from the proton-proton chain, and higher-mass stars that are supported principally by the carbon cycle. Below the end of the main sequence (masses less than 0.075 M,⊙) lie the brown dwarfs that occupy half of class L and all of class T (the latter under 1400 K or 2060◦F). These shine both from gravitational energy and from fusion of their natural deuterium. Their low-mass limit is unknown. -

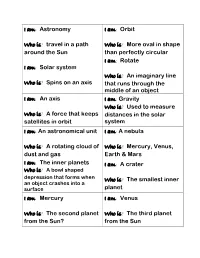

I Am: Astronomy Who Is? Travel in a Path Around

I am: Astronomy I am: Orbit Who is? travel in a path Who is? More oval in shape around the Sun than perfectly circular I am: Rotate I am: Solar system Who is? An imaginary line Who is? Spins on an axis that runs through the middle of an object I am: An axis I am: Gravity Who is? Used to measure Who is? A force that keeps distances in the solar satellites in orbit system I am: An astronomical unit I am: A nebula Who is? A rotating cloud of Who is? Mercury, Venus, dust and gas Earth & Mars I am: The inner planets I am: A crater Who is? A bowl shaped depression that forms when The smallest inner an object crashes into a Who is? surface planet I am: Mercury I am: Venus Who is? The second planet Who is? The third planet from the Sun? from the Sun I am: Earth I am: Revolve Who is? The fourth planet Who is? The path made from the Sun? during a revolution around the Sun I am: Mars I am: Asteroids Who is? Small, rocky Who is? Beyond the objects that orbit the Sun asteroid belt I am: Elliptical I am: The outer planets Who is? The Sun and all it’s Who is? So large that all satellites other planets could fit in it I am: Jupiter I am: Saturn Who is? The second largest Who is? 4 times larger than planet in the solar system Earth? I am: Uranus I am: Comets Who is? Frozen chunks of Who is? Pieces of rock or ice, gas and dust metal in space, smaller than a few hundred meters I am: Meteoroids I am: Meteor Who is? Streak of light from Who is? Meteor that hits a burning meteoroid the Earth’s surface I am: Meteorite I am: Nuclear fusion Who is? A reaction -

198 4Apj. . .211 . .7 91N the Astrophysical Journal, 277:791-805

91N .7 . The Astrophysical Journal, 277:791-805, 1984 February 15 © 1984. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. .211 . 4ApJ. 198 EVOLUTION OF 8-10 M0 STARS TOWARD ELECTRON CAPTURE SUPERNOVAE. I. FORMATION OF ELECTRON-DEGENERATE O + Ne + Mg CORES Ken’ichi Nomoto1 Laboratory for Astronomy and Solar Physics, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Received 1983 March 4; accepted 1983 July 12 ABSTRACT Helium cores in stars with masses near 10 M0 are evolved from the helium burning phase; the outer edge of the core is fitted to the boundary conditions at the bottom of the hydrogen-rich envelope. Two {0) cases with initial helium core mass of MH = 2.6MG (case 2.6) and 2.4 M0 (case 2.4) are studied. Both cores spend the carbon burning phase under nondegenerate condition and leave O + Ne + Mg cores. Further evolution depends on the mass of the O + Ne + Mg core, Mc. For case 2.6, Mc exceeds a critical mass for neon ignition (1.37 M0) so that a strong off-center neon flash is ignited. The neon and oxygen flashing layer moves inward. For case 2.4, on the other hand, neon is not ignited because Mc is smaller than 1.37 M0. Then the O + Ne + Mg core becomes strongly degenerate and a dredge-up of a helium layer by the penetrating surface convection zone starts. Further evolution up through the core collapse which is triggered by electron 24 20 (0) captures on Mg and Ne must be common to cases with Mh = 2.0-2.5 M0 (i.e., stellar mass of 8-10 M0). -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study. -

Optical Counterparts of ROSAT X-Ray Sources in Two Selected Fields at Low

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. sbg˙comsge˙ed c ESO 2018 October 16, 2018 Optical counterparts of ROSAT X-ray sources in two selected fields at low vs. high Galactic latitudes J. Greiner1, G.A. Richter2 1 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur extraterrestrische Physik, 85740 Garching, Germany 2 Sternwarte Sonneberg, 96515 Sonneberg, Germany Received 14 October 2013 / Accepted 12 August 2014 ABSTRACT Context. The optical identification of large number of X-ray sources such as those from the ROSAT All-Sky Survey is challenging with conventional spectroscopic follow-up observations. Aims. We investigate two ROSAT All-Sky Survey fields of size 10◦× 10◦ each, one at galactic latitude b = 83◦ (26 Com), the other at b = –5◦ (γ Sge), in order to optically identify the majority of sources. Methods. We used optical variability, among other more standard methods, as a means of identifying a large number of ROSAT All- Sky Survey sources. All objects fainter than about 12 mag and brighter than about 17 mag, in or near the error circle of the ROSAT positions, were tested for optical variability on hundreds of archival plates of the Sonneberg field patrol. Results. The present paper contains probable optical identifications of altogether 256 of the 370 ROSAT sources analysed. In partic- ular, we found 126 AGN (some of them may be misclassified CVs), 17 likely clusters of galaxies, 16 eruptive double stars (mostly CVs), 43 chromospherically active stars, 65 stars brighter than about 13 mag, 7 UV Cet stars, 3 semiregular resp. slow irregular variable stars of late spectral type, 2 DA white dwarfs, 1 Am star, 1 supernova remnant and 1 planetary nebula.