EUI RSCAS Working Paper 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiopodlasie.Pl Wygenerowano W Dniu 2021-09-25 10:49:22

Radiopodlasie.pl Wygenerowano w dniu 2021-09-25 10:49:22 Kto wejdzie do PE? Karol Karski, Krzysztof Jurgiel, Adam Bielan, Zbigniew Kuźmiuk, Elżbieta Kruk i Beata Mazurek(PiS), Tomasz Frankowski, Jarosław Kalinowski i Krzysztof Hetman (KE)- najprawdopodobniej wejdą do Parlamentu Europejskiego. Wszyscy kandydowali w okręgach obejmujących nasz region. Prognozy są oparte na sondażu exit-poll, co oznacza, że nazwiska kandydatów, którzy obejmą mandaty, mogą się jeszcze zmienić. Prawdopodobne nazwiska europarlamentarzystów podaje Informacyjna Agencja Radiowa. Prawo i Sprawiedliwość zdobyło najwięcej, 42,4 procent głosów, w wyborach do Parlamentu Europejskiego - wynika z sondażu exit-poll zrealizowanego przez IPSOS dla telewizji TVP, Polsat i TVN. Drugie miejsce w badaniu prowadzonym dziś przed lokalami wyborczymi zajęła Koalicja Europejska - 39,1 procent. Jeśli wyniki sondażu potwierdzą się, do Parlamentu Europejskiego dostaną się także kandydaci Wiosny - 6,6 procent oraz Konfederacji - 6,1 procent. Pięcioprocentowego prgu nie przekroczyły komitety Kukiz'15 - 4,1 procent oraz Lewica Razem - 1,3 procent. Prognozowana frekwencja wyniosła 43 procent - wynika z sondażu exit-poll. Zgodnie z sondażem, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość wygrało w siedmiu okręgach (warmińsko-mazurskie z podlaskim, Mazowsze, Łódzkie, Lubelskie, Podkarpacie, Małopolska ze Świętokrzyskiem oraz Śląsk). W sześciu okręgach wygrała Koalicja Europejska (Pomorze, kujawsko-pomorskie, Warszawa, Wielkopolska, Dolny Śląsk z Opolszczyzną oraz Lubuskie z Zachodniopomorskim). Z prognozy podziału mandatów wynika, że przy takich wynikach, jakie przyniósł sondaż exit-poll, PiS miałby w Parlamencie Europejskim 24 mandaty, Koalicja Europejska - 22 mandaty, a Wiosna i Konfederacja - po trzy mandaty. Zgodnie z sondażem, w okręgu obejmującym Pomorze dwa mandaty zdobyła Koalicja Europejska (Magdalena Adamowicz oraz najprawdopodobniej Janusz Lewandowski), a jeden Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (najprawdopodobniej Anna Fotyga). -

EP Elections 2014

EP Elections 2014 Biographies of new MEPs Please find the biographies of all the new MEPs elected to the 8th European Parliamentary term. The information has been collated from published sources and, in many cases, subject to translation from the native language. We will be contacting all MEPs to add to their biographical information over the summer, which will all be available on Dods People EU in due course. EU Elections 2014 Source: European Parliament- 1 - EP Overview (13/06/2014) List of countries: Austria Germany Poland Belgium Greece Portugal Bulgaria Hungary Romania Croatia Ireland Slovakia Cyprus Italy Slovenia Czech Latvia Spain Republic Denmark Lithuania Sweden United Estonia Luxembourg Kingdom Finland Malta France Netherlands EU Elections 2014 - 2 - Austria o People's Party (ÖVP) > EPP o Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) > S&D o Freedom Party (FPÖ) > NI o The Greens (GRÜNE) > Greens/EFA o New Austria (NEOS) > ALDE People’s Party (ÖVP) Claudia Schmidt (ÖVP, Austria) 26 April 1963 (FEMALE) Political: Councils/Public Bodies Member, Municipal Council, City of Salzburg 1999-; Chair, Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) Parliamentary Group, Salzburg Municipal Council 2004-09; Member, responsible for construction and urban development, Salzburg city government, 2009- Party posts: ÖVP: Vice-President, Salzburg, Member of the Board, Salzburg, Political Interest: Disability (social affairs) Personal: Non-political Career: Disability support institution (Lebenshilfe) Salzburg: Manager for special needs education 1989-1996, Officer responsible for -

En En Joint Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2014-2019 Plenary sitting B8-0190/2017 } B8-0192/2017 } B8-0195/2017 } B8-0198/2017 } B8-0221/2017 } RC1 15.3.2017 JOINT MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION pursuant to Rules 135(5) and 123(4) of the Rules of Procedure replacing the motions by the following groups: Verts/ALE (B8-0190/2017) ECR (B8-0192/2017) S&D (B8-0195/2017) ALDE (B8-0198/2017) PPE (B8-0221/2017) on the Ukrainian prisoners in Russia and the situation in Crimea (2017/2596(RSP)) Cristian Dan Preda, Tunne Kelam, Tomáš Zdechovský, Jaromír Štětina, Marijana Petir, Jarosław Wałęsa, Pavel Svoboda, Ivan Štefanec, Milan Zver, Brian Hayes, David McAllister, Eduard Kukan, Bogdan Brunon Wenta, Laima Liucija Andrikienė, József Nagy, Mairead McGuinness, Michaela Šojdrová, Roberta Metsola, Romana Tomc, Patricija Šulin, Maurice Ponga, Sven Schulze, Csaba Sógor, Željana Zovko, Ivana Maletić, Stanislav Polčák, Deirdre Clune, Luděk Niedermayer, Giovanni La Via, Claude Rolin, Adam Szejnfeld, Lorenzo Cesa, Jiří Pospíšil, Dariusz Rosati, Sandra Kalniete, Dubravka Šuica, Jerzy Buzek, Elżbieta Katarzyna Łukacijewska, Therese Comodini Cachia, Anna Maria Corazza Bildt, Krzysztof Hetman, RC\1120280EN.docx PE598.543v01-00 } PE598.545v01-00 } PE598.548v01-00 } PE598.551v01-00 } PE598.554v01-00 } RC1 EN United in diversity EN Bogdan Andrzej Zdrojewski, Andrey Kovatchev, Inese Vaidere, Anna Záborská, José Ignacio Salafranca Sánchez-Neyra, Elmar Brok on behalf of the PPE Group Victor Boştinaru, Soraya Post, Marju Lauristin, Julie Ward on behalf of the S&D Group Charles Tannock, Karol Karski, -

Adam Barabasz the Polish Elections to the European Parliament in 2014 As Shown in the Polish Press

Adam Barabasz The Polish elections to the European Parliament in 2014 as shown in the Polish press Rocznik Integracji Europejskiej nr 8, 317-331 2014 Nr 8 ROCZNIK INTEGRACJI EUROPEJSKIEJ 2014 ADAM BARABASZ DOI: 10.14746/rie.2014.8.22 Poznań The Polish elections to the European Parliament in 2014 as shown in the Polish press Poland has already had three European elections since its accession to the European Union. On May 25, 2014, the Polish public elected fifty-one members of the European Parliament (MEPs) for another term of five years. Similarly to the 2004 and 2009 elec tions, the main concern of Polish journalists was voter turnout. This time, the turnout amounted to 23.84% giving the leading position to the Civic Platform (PO) party, which won 32.13% of votes. Law and Justice (PiS) came second with 31.78% votes, followed by the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD - 9.44%), the New Right (NP - 7.15%) and the Polish People’s Party (PSL - 6.8%). United Poland, the coalition Europa Plus-Your Move (EPTR), Poland Together, the National Movement, the Green Party of Poland and the Direct Democracy Election Committee failed to achieve the election threshold of 5%. The most influential Polish newspapers and magazines were assessing the strategy of different parties’ election committees throughout the entire campaign. New faces of the campaign, alongside the profiles of those MEPs who were battling to get to Strasbourg once again, were presented. The style of the campaign, the language of TV election spots and the means the parties used in order to generate social support were stressed. -

Tusk Refuses to Sign EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights

WEEKLY 3,00 zloty (with 7% VAT) Published by: Jargon Media Sp. z o.o. Index Number: 236683 ISSN: 1898-4762 NO. 31 WWW.KRAKOWPOST.COM DECEMBER 6-DECEMBER 12, 2007 Tusk refuses to sign EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights Poles released from Swedish camp Sixty Poles say a Gdansk labor recruiting agency lured them to Sweden with promises of jobs that didn’t exist – and they ended up crushing rocks 2 War launched over in vitro fertilization Health Minister Ewa Kopacz says that she will sponsor a plan to finance in vitro fertilization for Polish couples who are childless, usually as a result of infertility 3 Michnik named Tusk is afraid that if Poland signs the rights charter, which Kaczynski opposes, the president will use his influence to prevent the reform treaty from becoming law. Georgia monitor Kinga Rodkiewicz economic and social rights that EU residents with the charter. After the election, Kazynski let Tusk know STAFF JOURNALIST should enjoy. The rights are divided into six “I don’t notice, in contrast with some ob- he would fight charter ratification. Tusk decid- Former dissident-turned editor sections: Dignity, Freedoms, Equality, Solidar- servers – including Polish bishops – important ed to capitulate on that issue so he could obtain Adam Michnik has been made Prime Minister Donald Tusk has backed ity, Citizens’ Rights and Justice. dangers which were written into the charter,” ratification of the Reform Treaty – the first po- the EU’s mediator on press away from a campaign pledge to sign the The charter includes such traditional rights Tusk said. -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Results

Briefing June 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Results Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 7 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 3 seats 2 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Heinz Christian Strache 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide 6. Alexander Bernhuber 7. Barbara Thaler NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 1. Maria Arena* Socialist Party (PS) Christian Social Party 3. Johan Van Overtveldt 2. Marc Tarabella* (S&D) 2 seats (CSP) (EPP) 1 seat New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) 1. Olivier Chastel (Greens/EFA) Reformist 2. Frédérique Ries* 4 seats Movement (MR) (ALDE) 2 seats 1. Philippe Lamberts* 2. Saskia Bricmont 1. Guy Verhofstadt* Ecolo (Greens/EFA) 2. Hilde Vautmans* 2 seats Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open 1. Benoît Lutgen Humanist VLD) (ALDE) 2 seats democratic centre (cdH) (EPP) 1 seat 1. Kris Peeters Workers’ Party of 1. -

Table of Contents

October, 2017 Table of contents ABOUT HELSINKI FOUNDATION FOR HUMAN RIGHTS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS IN POLAND – ATTACKS ON THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL TRIBUNAL 5 Origins of the crisis 5 Invalidation of the election of the judges and the election of new judges 6 Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 3 December 2015 7 Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 9 December 2015 7 “Remedial” Act on the Constitutional Tribunal 8 The discontinuation of proceedings before the Constitutional Tribunal concerning the resolutions reversing the appointment of 5 judges 10 The Constitutional Tribunal’s judgement on the amendment of December 2015 10 Venice Commission opinion 11 Government’s refusal to publish judgments of the Constitutional Tribunal – risk of legal duality 11 New draft of the Act on the Constitutional Tribunal 12 The Constitutional Tribunal’s ruling on the second Act on the Constitutional Tribunal 14 Venice Commission’s opinion on the Act on the Constitutional Tribunal of July 2016 15 Three new acts regulating the works of the Constitutional Tribunal 16 The appointment of the new President of the Constitutional Tribunal 16 1 The motion of the Prosecutor General 17 The Constitutional Tribunal after the reforms 17 Conclusions 18 THE “REFORM” OF THE JUSTICE SYSTEM 19 The draft Act on the National Council of the Judiciary 19 Act on the Supreme Court 20 Act on the system of common courts 21 Presidential vetoes and new draft laws on the Supreme Court and National Council of the Judiciary 22 Conclusions 23 -

Electoral Lists Ahead of the Elections to the European Parliament from a Gender Perspective ______

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs ____________________________________________________________________________________________ IT ITALY This case study presents the situation in Italy as regards the representation of men and women on the electoral lists in the elections for the European Parliament 2014. The first two tables indicate the legal situation regarding the representation of men and women on the lists and the names of all parties and independent candidates which will partake in these elections. The subsequent tables are sorted by those political parties which were already represented in the European Parliament between 2009 and 2014 and will firstly indicate whether and how a party quota applies and then present the first half of the candidates on the lists for the 2014 elections. The legal situation in Italy regarding the application of gender quotas 2009-2014: 731 Number of seats in the EP 2014-2019: 73 System type: Proportional representation with preferential voting, Hare/Niemeyer system. Each voter has up to three preferential votes. Distribution of seats according to the Hare/Niemeyer system Threshold: 4% Number of constituencies: five constituencies. o North-West o North-East o Centre Electoral System type for o South the EP election 2014 o Islands Allocation of seats: The absolute number of preferential votes determines the selection of the candidates. Compulsory voting: no. Legal Sources : Law n. 18 of 24 January 1979 as amended and supplemented by laws n. 61 of 9 April 1984, n. 9 of 18 January 1989 and decree n. 408 of 24 June 1994 (right to vote and to stand as a candidate for citizens of the Union), as amended by law n. -

The Foundation for European Reform NEW DIRECTION the Foundation for European Reform

the foundation for european reform NEW DIRECTION The Foundation for European Reform is a Brussels-based free market, euro-realist think- tank and publisher, established in 2010 under the patronage of Baroness Thatcher. We have satellite offices in London and Warsaw. New Direction is registered in Belgium as a not-for-profit organisation (ASBL) and is partly funded by the European Parliament. This is the report of New Direction activities in 2014 and the European Parliament assumes no responsibility for facts and opinions expressed in this publication. ADVANCING BUILDING CONSERVATIVISM A POPULAR AND A EUROPE OF MOVEMENT NATION STATES New Direction is affiliated to the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (AECR) and draws its inspiration from the founding principles of our Conservative & Reformist Our vision is for the advancement of small Movement contained in the 2009 Prague Declaration. government, private property, free enterprise, lower taxes, family values, individual freedom, strong defence, a Europe of nation states and a strong trans-Atlantic alliance. 4 5 Political parties represented in our movement: Danish People’s Party, Denmark Conservative and Reformists, Italy New Republic, Romania Our movement has representatives in the European Parliament, the NATO Parliamentary Assembly, the Council of Europe, the Prosperous Armenia Party, Armenia Faroese People’s Party, Faroe Islands Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania, Ordinary People and Independent Committee of the Regions and the Congress of Local and Regional Lithuania -

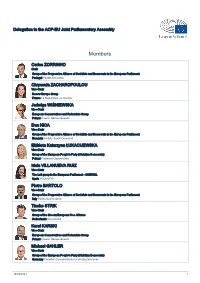

List of Members

Delegation to the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly Members Carlos ZORRINHO Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Portugal Partido Socialista Chrysoula ZACHAROPOULOU Vice-Chair Renew Europe Group France La République en marche Jadwiga WIŚNIEWSKA Vice-Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Dan NICA Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Romania Partidul Social Democrat Elżbieta Katarzyna ŁUKACIJEWSKA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska Idoia VILLANUEVA RUIZ Vice-Chair The Left group in the European Parliament - GUE/NGL Spain PODEMOS Pietro BARTOLO Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Tineke STRIK Vice-Chair Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Netherlands GroenLinks Karol KARSKI Vice-Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Michael GAHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands 26/09/2021 1 Marie-Pierre VEDRENNE Vice-Chair Renew Europe Group France Mouvement Démocrate Inese VAIDERE Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Latvia Partija "VIENOTĪBA" Maria ARENA Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Belgium Parti Socialiste -

Sprawozdanie Nt. Obsady Stanowisk W Parlamencie Europejskim 2014-2019 Bruksela, 8 Lipca 2014 R

Bruksela, dnia 8 lipca 2014 r. Sprawozdanie nr 64/2014 Sprawozdanie nt. obsady stanowisk w Parlamencie Europejskim 2014-2019 Bruksela, 8 lipca 2014 r. Metodologia Podstawą rozstrzygnięć pomiędzy grupami politycznymi, jak i wewnątrz grup politycznych dotyczących obsady kluczowych stanowisk w PE jest system d’Hondta. Cały proces przebiega w toku negocjacji politycznych, w których ścierają się interesy grup politycznych oraz delegacji narodowych. W grupach politycznych, w zależności od liczby uzyskanych mandatów, tworzy się specjalny system punktów, przy wykorzystaniu którego dokonuje się podziału konkretnych stanowisk. W całym procesie dba się o zrównoważoną reprezentację dużych delegacji krajowych we wszystkich gremiach – np. także na stanowiskach wiceprzewodniczących PE (stanowiska reprezentacyjne o mniejszym znaczeniu politycznym, ale ważne dla prestiżu całego PE). I. Przewodniczący PE Martin Schulz (S&D/Niemcy), kadencja lipiec 2014 – grudzień 2016; uzyskał poparcie 409 eurodeputowanych; Wyniki pozostałych kandydatów: Sajjad Karim (ECR/Wielka Brytania) – 101 głosów; Pablo Iglesias (GUE/NGL, Hiszpania) – 51 głosów; Ulrike Lunacek (Zieloni/EFA, Austria) – 51 głosów. Przewodnictwo PE w kolejnej 2,5 letniej kadencji przypadnie przedstawicielowi EPP - spekuluje się, że będzie to Alain Lamassoure (Francja). 1 II. 14 Wiceprzewodniczących PE1: kadencja lipiec 2014 – grudzień 2016. EPP 1. Ildikó Gáll-Pelcz (Węgry): 400 głosów, wybrany w I turze 2. Mairead McGuiness (Irlandia): 441 głosów, wybrany w I turze 3. Antonio Tajani (Włochy): 452 głosy, wybrany w I turze 4. Ramón Luis Valcárcel Siso (Hiszpania): 406 głosów, wybrany w I turze 5. Adina Ioana Valean (Rumunia): 394 głosy, wybrana w I turze 6. Rainer Wieland (Niemcy): 437 głosów, wybrany w I turze S&D 1. Corina Creţu (Rumunia): 406 głosów, wybrana w II turze 2. -

Minutes of the Sitting of 15 March 2017 (2017/C 430/03)

14.12.2017 EN Off icial Jour nal of the European Union C 430/173 Wednesday 15 March 2017 MINUTES OF THE SITTING OF 15 MARCH 2017 (2017/C 430/03) Contents Page 1. Opening of the sitting . 177 2. Debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law (announcement of motions for 177 resolutions tabled) . 3. Implementing measures (Rule 106) . 179 4. Delegated acts (Rule 105(6)) . 179 5. Transfers of appropriations . 180 6. Documents received . 180 7. Conclusions of the European Council meeting of 9 and 10 March 2017, including the Rome Declaration 181 (debate) . 8. Negotiations ahead of Parliament's first reading (Rule 69c) . 181 9. Voting time . 182 9.1. EU-Brazil Agreement: modification of concessions in the schedule of Croatia in the course of its 182 accession *** (Rule 150) (vote) . 9.2. Launch of automated data exchange with regard to vehicle registration data in Denmark * 182 (Rule 150) (vote) . 9.3. Launch of automated data exchange with regard to DNA data in Greece * (Rule 150) (vote) . 182 9.4. Food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection 183 products ***II (vote) . 9.5. Use of the 470-790 MHz frequency band in the Union ***I (vote) . 183 9.6. Obstacles to EU citizens' freedom to move and work in the Internal Market (vote) . 183 9.7. Commission's approval of Germany's revised plan to introduce a road toll (vote) . 184 9.8. Guidelines for the 2018 budget — Section III (vote) . 184 10.