Sexual Selection and Signalling in the Lizard Platysaurus Minor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camera Traps Unravel the Effects of Weather Conditions and Predator Presence on the Activity Levels of Two Lizards

RESEARCH ARTICLE Some Like It Hot: Camera Traps Unravel the Effects of Weather Conditions and Predator Presence on the Activity Levels of Two Lizards Chris Broeckhoven*☯, Pieter le Fras Nortier Mouton☯ Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract It is generally assumed that favourable weather conditions determine the activity levels of lizards, because of their temperature-dependent behavioural performance. Inactivity, how- ever, might have a selective advantage over activity, as it could increase survival by reduc- ing exposure to predators. Consequently, the effects of weather conditions on the activity OPEN ACCESS patterns of lizards should be strongly influenced by the presence of predators. Using remote Citation: Broeckhoven C, Mouton PlFN (2015) Some camera traps, we test the hypothesis that predator presence and weather conditions inter- Like It Hot: Camera Traps Unravel the Effects of act to modulate daily activity levels in two sedentary cordylid lizards, Karusasaurus polyzo- Weather Conditions and Predator Presence on the nus and Ouroborus cataphractus. While both species are closely related and have a fully Activity Levels of Two Lizards. PLoS ONE 10(9): overlapping distribution, the former is a fast-moving lightly armoured lizard, whereas the lat- e0137428. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137428 ter is a slow-moving heavily armoured lizard. The significant interspecific difference in anti- Editor: Daniel E. Naya, Universidad de la Republica, predator morphology and consequently differential vulnerability to aerial and terrestrial URUGUAY predators, allowed us to unravel the effects of predation risk and weather conditions on Received: March 16, 2015 activity levels. -

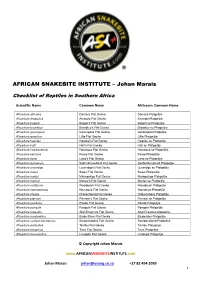

Johan Marais

AFRICAN SNAKEBITE INSTITUTE – Johan Marais Checklist of Reptiles in Southern Africa Scientific Name Common Name Afrikaans Common Name Afroedura africana Damara Flat Gecko Damara Platgeitjie Afroedura amatolica Amatola Flat Gecko Amatola Platgeitjie Afroedura bogerti Bogert's Flat Gecko Bogert se Platgeitjie Afroedura broadleyi Broadley’s Flat Gecko Broadley se Platgeitjie Afroedura gorongosa Gorongosa Flat Gecko Gorongosa Platgeitjie Afroedura granitica Lillie Flat Gecko Lillie Platgeitjie Afroedura haackei Haacke's Flat Gecko Haacke se Platgeitjie Afroedura halli Hall's Flat Gecko Hall se Platgeitjie Afroedura hawequensis Hawequa Flat Gecko Hawequa se Platgeitjie Afroedura karroica Karoo Flat Gecko Karoo Platgeitjie Afroedura langi Lang's Flat Gecko Lang se Platgeitjie Afroedura leoloensis Sekhukhuneland Flat Gecko Sekhukhuneland Platgeitjie Afroedura loveridgei Loveridge's Flat Gecko Loveridge se Platgeitjie Afroedura major Swazi Flat Gecko Swazi Platgeitjie Afroedura maripi Mariepskop Flat Gecko Mariepskop Platgeitjie Afroedura marleyi Marley's Flat Gecko Marley se Platgeitjie Afroedura multiporis Woodbush Flat Gecko Woodbush Platgeijtie Afroedura namaquensis Namaqua Flat Gecko Namakwa Platgeitjie Afroedura nivaria Drakensberg Flat Gecko Drakensberg Platgeitjie Afroedura pienaari Pienaar’s Flat Gecko Pienaar se Platgeitjie Afroedura pondolia Pondo Flat Gecko Pondo Platgeitjie Afroedura pongola Pongola Flat Gecko Pongola Platgeitjie Afroedura rupestris Abel Erasmus Flat Gecko Abel Erasmus platgeitjie Afroedura rondavelica Blyde River -

Patterns of Species Richness, Endemism and Environmental Gradients of African Reptiles

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Patterns of species richness, endemism ARTICLE and environmental gradients of African reptiles Amir Lewin1*, Anat Feldman1, Aaron M. Bauer2, Jonathan Belmaker1, Donald G. Broadley3†, Laurent Chirio4, Yuval Itescu1, Matthew LeBreton5, Erez Maza1, Danny Meirte6, Zoltan T. Nagy7, Maria Novosolov1, Uri Roll8, 1 9 1 1 Oliver Tallowin , Jean-Francßois Trape , Enav Vidan and Shai Meiri 1Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, ABSTRACT 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel, 2Department of Aim To map and assess the richness patterns of reptiles (and included groups: Biology, Villanova University, Villanova PA 3 amphisbaenians, crocodiles, lizards, snakes and turtles) in Africa, quantify the 19085, USA, Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, PO Box 240, Bulawayo, overlap in species richness of reptiles (and included groups) with the other ter- Zimbabwe, 4Museum National d’Histoire restrial vertebrate classes, investigate the environmental correlates underlying Naturelle, Department Systematique et these patterns, and evaluate the role of range size on richness patterns. Evolution (Reptiles), ISYEB (Institut Location Africa. Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite, UMR 7205 CNRS/EPHE/MNHN), Paris, France, Methods We assembled a data set of distributions of all African reptile spe- 5Mosaic, (Environment, Health, Data, cies. We tested the spatial congruence of reptile richness with that of amphib- Technology), BP 35322 Yaounde, Cameroon, ians, birds and mammals. We further tested the relative importance of 6Department of African Biology, Royal temperature, precipitation, elevation range and net primary productivity for Museum for Central Africa, 3080 Tervuren, species richness over two spatial scales (ecoregions and 1° grids). We arranged Belgium, 7Royal Belgian Institute of Natural reptile and vertebrate groups into range-size quartiles in order to evaluate the Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny, role of range size in producing richness patterns. -

Causes and Consequences of Body Armour in the Group-Living Lizard, Ouroborus Cataphractus (Cordylidae)

Causes and consequences of body armour in the group-living lizard, Ouroborus cataphractus (Cordylidae) by Chris Broeckhoven Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. P. le Fras N. Mouton March 2015 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Cordylidae is a family of predominantly rock-dwelling sit-and-wait foraging lizards endemic to southern Africa. The significant variation in spine length and extent of osteoderms among taxa makes the family an excellent model system for studying the evolution of body armour. Specifically, the Armadillo lizard (Ouroborus cataphractus) offers an ideal opportunity to investigate the causes and consequences of body armour. Previous studies have hypothesised that high terrestrial predation pressure, resulting from excursions to termite foraging ports away from the safety of the shelter, has led to the elaboration of body armour and a unique tail-biting behaviour. The reduction in running speed associated with heavy body armour, in turn, appears to have led to the evolution of group-living behaviour to lower the increased aerial predation risk. -

A Taxonomic Revision of the South-Eastern Dragon Lizards of the Smaug Warreni (Boulenger) Species Complex in Southern Africa, Wi

A taxonomic revision of the south-eastern dragon lizards of the Smaug warreni (Boulenger) species complex in southern Africa, with the description of a new species (Squamata: Cordylidae) Michael F. Bates1,2,* and Edward L. Stanley3,* 1 Department of Herpetology, National Museum, Bloemfontein, South Africa 2 Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa 3 Department of Herpetology, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL, USA * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT A recent multilocus molecular phylogenyofthelargedragonlizardsofthegenus Smaug Stanley et al. (2011) recovered a south-eastern clade of two relatively lightly- armoured, geographically-proximate species (Smaug warreni (Boulenger, 1908) and S. barbertonensis (Van Dam, 1921)). Unexpectedly, S. barbertonensis was found to be paraphyletic, with individuals sampled from northern Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) being more closely related to S. warreni than to S. barbertonensis from the type locality of Barberton in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Examination of voucher specimens used for the molecular analysis, as well as most other available museum material of the three lineages, indicated that the ‘Eswatini’ lineage—including populations in a small area on the northern Eswatini–Mpumalanga border, and northern KwaZulu–Natal Province in South Africa—was readily distinguishable from S. barbertonensis sensu stricto (and S. warreni) by its unique dorsal, lateral and ventral colour patterns. In order to further assess the taxonomic status of the three populations, a detailed Submitted 26 September 2019 Accepted 7 January 2020 morphological analysis was conducted. Multivariate analyses of scale counts and Published 25 March 2020 body dimensions indicated that the ‘Eswatini’ lineage and S. -

Population Genetics and Sociality in the Sungazer (Smaug Giganteus)

Population genetics and sociality in the Sungazer (Smaug giganteus) Shivan Parusnath Doctoral Thesis Supervisors: Prof. Graham Alexander Prof. Krystal Tolley Prof. Desire Dalton Prof. Antoinette Kotze A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 30th October 2020 “My philosophy is basically this, and this is something that I live by, and I always have, and I always will: Don't ever, for any reason, do anything, to anyone, for any reason, ever, no matter what, no matter where, or who, or who you are with, or where you are going, or where you've been, ever, for any reason whatsoever.” - Michael G. Scott DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at any other University. All protocols were approved by the University of the Witwatersrand Animal Ethics Screening Committee (2014/56/B; 2016/06/30/B), and the National Zoological Garden, South African National Biodiversity Institute (NZG SANBI) Research, Ethics and Scientific Committee (P14/18). Permits to work with Threatened or Protected Species were granted by the South African Department of Environmental Affairs (TOPS59). Permits to collect samples in the Free State and Mpumalanga provinces were provided by Department of Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs (01/34741; JM938/2017) and Mpumalanga Tourism and Parks Agency (MPB. 5519) respectively. Research approval in terms of Section 20 of the Animal Diseases Act (35 of 1984) was granted by the South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (12/11/1/1/18). -

Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles

diversity Article Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, and Tuatara in the EU on the Basis of a Risk Assessment Model (RAM) and Aquatic Species Invasiveness Screening Kit (AS-ISK) OldˇrichKopecký *, Anna Bílková, Veronika Hamatová, Dominika K ˇnazovická, Lucie Konrádová, Barbora Kunzová, Jana Slamˇeníková, OndˇrejSlanina, Tereza Šmídová and Tereza Zemancová Department of Zoology and Fisheries, Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, Praha 6 - Suchdol 165 21, Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (V.H.); [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (L.K.); [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (B.K.); [email protected] (O.S.); [email protected] (T.S.); [email protected] (T.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-22438-2955 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 9 September 2019; Published: 13 September 2019 Abstract: Because biological invasions can cause many negative impacts, accurate predictions are necessary for implementing effective restrictions aimed at specific high-risk taxa. The pet trade in recent years became the most important pathway for the introduction of non-indigenous species of reptiles worldwide. Therefore, we decided to determine the most common species of lizards, snakes, and crocodiles traded as pets on the basis of market surveys in the Czech Republic, which is an export hub for ornamental animals in the European Union (EU). Subsequently, the establishment and invasion potential for the entire EU was determined for 308 species using proven risk assessment models (RAM, AS-ISK). Species with high establishment potential (determined by RAM) and at the same time with high potential to significantly harm native ecosystems (determined by AS-ISK) included the snakes Thamnophis sirtalis (Colubridae), Morelia spilota (Pythonidae) and also the lizards Tiliqua scincoides (Scincidae) and Intellagama lesueurii (Agamidae). -

Squamata: Cordylidae: Platysaurinae) from Southern Africa

Zootaxa 3986 (2): 173–192 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3986.2.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:986B0CFE-77D7-453F-8708-5F60F79624BE A new species of spectacularly coloured flat lizard Platysaurus (Squamata: Cordylidae: Platysaurinae) from southern Africa MARTIN J. WHITING1,5, WILLIAM R. BRANCH2,3, MITZY PEPPER4 & J. SCOTT KEOGH4 1Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 2Port Elizabeth Museum, P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, Republic of South Africa 3Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P O Box 77000, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 6031, South Africa 4Division of Evolution, Ecology and Genetics, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 5Corresponding author Abstract We describe a new species of flat lizard (Platysaurus attenboroughi sp. nov.) from the Richtersveld of the Northern Cape Province of South Africa and the Fish River Canyon region of southern Namibia. This species was formerly confused with P. capensis from the Kamiesberg region of Namaqualand, South Africa. Genetic analysis based on one mtDNA and two nDNA loci found Platysaurus attenboroughi sp. nov. to be genetically divergent from P. c ap e ns i s and these species can also be differentiated by a number of scalation characters, coloration and their allopatric distributions. To stabilize the tax- onomy the type locality of Platysaurus capensis A. Smith 1844 is restricted to the Kamiesberg region, Namaqualand, Northern Cape Province, South Africa. -

Catalog of the Family Cordylidae

Catalog of the Family Cordylidae Harold De Lisle 2016 Cover photo : Platysaurus orientalis, by Nilsroe CC BY-SA 4.0 Back cover : Ouroborus cataphractus in defence posture, by Hardaker Email: [email protected] CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …............................................................................. 1 CATALOG ….......................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS …................................................................. 20 REFERENCES . …................................................................................. 21 TAXON INDEX …................................................................................... 32 The Cordylidae is a family of small to medium-sized lizards that occur in southern and eastern Africa. They are commonly known as girdled lizards, spinytail lizards or girdle-tail lizards. Cordylid lizards are diurnal and mainly insectivorous. They are terrestrial, mostly inhabiting crevices in rocky terrain, although at least one species digs burrows and another lives under exfoliating bark on trees, and one genus lives mainly on grassy savannahs. They have short tongues covered with long papillae, flattened heads and bodies. The body scales possess osteoderms and have large, rectangular, scales, arranged in regular rows around the body and tail. Many species have rings of spines on the tail, that aid in wedging the animal into sheltering crevices, and also in dissuading predators. The body is often flattened, and in most species is box-like on cross-section, -

Social Structure and Spatial-Use in a Group-Living Lizard

SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND SPATIAL-USE IN A GROUP-LIVING LIZARD, CORDYLUS CATAPHRACTUS by Etienne Effenberger Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Department of Zoology, Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor P. le F. N. Mouton December 2004 II DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature:………………………… Date:………………………… III ABSTRACT There is overwhelming evidence that the Armadillo Lizard, Cordylus cataphractus, forms permanent aggregations, and that termites are possibly the most important component of the diet of this species. In addition, the spinose morphology and defensive tail-biting behaviour displayed by this lizard species strongly imply that individuals move away from the crevice, where they are more vulnerable to predation. Therefore the aim of this part of the study was to investigate whether C. cataphractus harvest termites at the termite foraging ports and to discuss the likely ecological implications of termitophagy for this species. A quadrate at the Graafwater study site, including several crevices housing C. cataphractus groups, was measured out. All the foraging ports of the subterranean harvester termite (Microhodotermes viator) present in the quadrate, were located and their positions recorded in respect to the distance from the nearest crevice housing lizards. The presence of C. cataphractus tracks at the foraging ports was used to verify whether individuals visited specific termite foraging ports. Tracks were found at foraging ports located at an average distance of 6.1 m, but were also located at foraging ports up to 20 m from the nearest crevice. -

Inglés AC27 Doc. 25.2 CONVENCIÓN SOBRE EL COMERCIO

Idioma original: inglés AC27 Doc. 25.2 CONVENCIÓN SOBRE EL COMERCIO INTERNACIONAL DE ESPECIES AMENAZADAS DE FAUNA Y FLORA SILVESTRES ____________ Vigésimo séptima reunión del Comité de Fauna Veracruz (México), 28 de abril – 3 de mayo de 2014 Interpretación y aplicación de la Convención Comercio y conservación de especies Nomenclatura normalizada NOMENCLATURA REVISADA PARA POICEPHALUS ROBUSTUS Y CORDYLUS 1. Este documento ha sido preparado por la Autoridad Científica de Sudáfrica*. 2. El informe adjunto sobre la sistemática y filogeografía del lorito robusto (Coetzer et al.) se inscribe en el marco siguiente: a) La nomenclatura actual adoptada por la CITES para Poicephalus robustus no está actualizada. Siguiendo esta taxonomía obsoleta, el lorito robusto, especie endémica y en peligro de Sudáfrica, está siendo actualmente objeto de comercio conjuntamente con P. r. suahelicus, lo que le dificulta la acción de conservación en Sudáfrica y el control del comercio de especímenes del lorito robusto. b) Se pide al Comité de Fauna que examine la nomenclatura revisada actualmente utilizada por la Unión Internacional de Ornitólogos y BirdLife Sudáfrica y recomiende que sea adoptada para los Apéndices y las listas de referencia de la CITES. 3. La publicación adjunta de Stanley et al. (2011) se inscribe en el marco siguiente: a) Una revisión taxonómica de la familia de lagartos subsahariana Cordylidae tuvo como resultado que las especies incluidas en el Apéndice II de la CITES dentro del género Cordylus ha sido transferida a los géneros Smaug, Ninurta, Pseudocordylus, Ouroborus, Karusasaurus, Namazonorus y Hemicordylus. b) Se puede generar confusión cuando los operadores comerciales utilicen los viejos y nuevos nombres. -

The Importance of Body Posture and Orientation in the Thermoregulation

The importance of body posture and orientation in the thermoregulation of Smaug giganteus, the Sungazer Wade Stanton-Jones School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg Supervisor: Prof Graham Alexander Wade Stanton-Jones Student Number: 601874 Abstract Body temperature (Tb) is the most influential factor affecting physiological processes in ectothermic animals. Reptiles use behavioural adjustments, i.e. shuttling behaviour and postural and orientation adjustments, such that a target Tb (Ttarget) can be attained. Ttarget is attained so that various physiological functions can occur within their respective thermal optima. The Sungazer, Smaug giganteus, is unique amongst the Cordylidae in that individuals inhabit self-excavated burrows in open grasslands, where conductive heating is restricted. Therefore, their Tbs are more likely influenced by postural and orientation adjustments than by conductive mechanisms. The purpose of this study was to measure the Ttarget of Sungazers and to assess the impact of body posture and orientation on thermoregulation in Sungazers. Thermocron® iButtons were modified to function as cloacal probes, set to record temperatures every minute and were inserted in the cloacas of 18 adult Sungazers. Sungazers were released at their respective burrows where camera traps recorded photographs every minute of the diurnal cycle to record behaviour. Copper models recorded the range of operative temperatures; an exposed model set up in “sungazing” posture, and a model inserted 0.5 m into an active Sungazer burrow. Data were successfully recorded from nine Sungazers. Sungazers achieved a Ttarget of 30.17 ± 1.35 ˚C (Mean ± SD) and remained at this range for 332.56 ± 180.60 minutes (Mean ± SD).