Feminine Bits: the Passive Bodies and Active Revisions of Cinderella, Snow White, Rapunzel, and Red Riding-Hood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Little Red Cap

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Little Red Cap filled with enticing books. She is filled with intense pleasure and SUMMARY excitement upon seeing all these books, her response to reading so many words described in terms resembling an As the speaker leaves behind the metaphorical neighborhood orgasm. of her childhood, there are fewer and fewer houses around, and the landscape eventually gives way to athletic fields, a local Time passes, however, and the speaker reflects on what ten factory, and garden plots, tended to by married men with the years together with the wolf has taught her. She compares the same submissive care they might show a mistress. The speaker oppressive nature of their relationship to a mushroom growing passes an abandoned railroad track and the temporary home of from, and thus figuratively choking, the mouth of a dead body. a recluse, before finally reaching the border between her She has learned that birds—implied to be representative of neighborhood and the woods. This is where she first notices poetry or art in general—and the thoughts spoken aloud by someone she calls "the wolf." trees (meaning, perhaps, that art comes only from experience). And she has also realized that she has become disenchanted He is easy to spot, standing in a clearing in the woods and with the wolf, both sexually and artistically, since he and his art proudly reading his own poetry out loud in a confident oice.v have grown old, repetitious, and uninspiring. The speaker notes the wolf's literary expertise, masculinity, and maturity—suggested by the book he holds in his large hands The speaker picks up an axe and attacks a willow tree and a fish, and by his thick beard stained with red wine. -

Corvus Review

CORVUS REVIEW WINTER 2016 ISSUE 4W 2 Letter from the Editor Welcome to 4W! It seems this little lit journal has really grown and turned into something quite fantastic. I’m very excited to present the work within this issue and genuinely hope you enjoy reading through. In terms of quality, I think this collection is of high caliber and the artists contained within these pages are truly talented individuals, the sort of work I hope you’ve come to expect from Corvus. Over the last little while, Corvus has achieved several milestones. We’re listed on Duotrope.com and NewPages.com. We’ve also hit over 1300 followers on Twitter and connected with many other little lit journals, talented editorial staff members, and contributors. We’ve also gained the attention of the Facebook community via our Facebook page. In short, it’s been both wonderful and rewarding to see this journal grow and develop, thanks primarily to our contributors and charitable donors. Corvus has also begun to offer writing services through Corvid Editing Services. Pop by www.corev.ink for more info. Thank you all so much for your commitment to Corvus and I look forward to making every issue as great (or greater) than the last. Happy Scribbling! Janine Mercer EIC, Corvus Review Table of Contents Poetry Prose Bella 4 Reeves-Murray 27-28 Stout 5 Half Pillow 29-35 Dougherty 6-7 Rowe 36 Kwalton 8 Pipher 37-39 Howerton 9 Lamberty 40-45 Vaccaro Nelkin 10 Grey 12-14 Tu 46-51 Miles 15 Geigley 52-58 Jacobs 16 Heger 59-64 Webb 17 Charpentier 65-68 Boggess 18 Sullivan 69-71 Mize 19 Mulhern 72-76 Johnson 20 Lynn 21-23 Price 77-86 Petras 24-25 Belle 87-90 Huffman 26 Schumacher 91 Mc Ivor 93-97 Hendrickson 98-100 Easton 101-106 Racklin 107-108 Hinton 109-113 Cover/Editors Bio 114 Chiasmus Lana Bella You no longer feel the urge to slam the door, instead, with a casual flick of your fingers, you set them loose, groaning toward their final berth. -

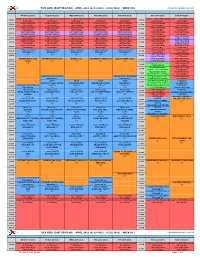

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Yabla German Lessons with Links to Videos Containing Examples Two

Yabla_German_Lessons 4/27/15 2:18 PM Yabla German Lessons with links to videos containing examples Two-way Prepositions Most commonly spoken German prepositions take the accusative or dative case (the genitive case is used more often in the written form). Some prepositions, such as bis, durch, für, gegen, je, ohne, um and wider, take only the accusative case. Others, like aus, außer, bei, gegenüber, mit, nach, seit, von and zu, take only the dative case. There are, however, certain prepositions that can take either the accusative or the dative case, depending on the context: an, auf, hinter, in, neben, über, unter, vor and zwischen. Even experienced German speakers can get it wrong sometimes, so although you've probably learned this before, this may be a good time to review these two-way (or dual) prepositions. The general rule to remember: if the preposition is dealing with "where" something is in a static sense, it takes the dative case; if it is dealing with motion or destination ("where to" or "what about") in an active sense, then it takes the accusative case. Der Spiegel hängt an der Wand. The mirror is hanging on the wall. Caption 34, Deutschkurs in Tübingen: Mehr Wechselpräpositionen Since the wall is where the mirror is statically hanging, the feminine noun die Wand takes the dative case in this context. Sie gehen an die Arbeit wieder. They're going to work again. Caption 29, Der Struwwelpeter: Hans Guck-in-die-Luft Since work is where they are actively going to, the feminine noun die Arbeit takes the accusative case. -

Download 2018–2019 Catalogue of New Plays

Catalogue of New Plays 2018–2019 © 2018 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Take a look at the “New Plays” section of this year’s catalogue. You’ll find plays by former Pulitzer and Tony winners: JUNK, Ayad Akhtar’s fiercely intelligent look at Wall Street shenanigans; Bruce Norris’s 18th century satire THE LOW ROAD; John Patrick Shanley’s hilarious and profane comedy THE PORTUGUESE KID. You’ll find plays by veteran DPS playwrights: Eve Ensler’s devastating monologue about her real-life cancer diagnosis, IN THE BODY OF THE WORLD; Jeffrey Sweet’s KUNSTLER, his look at the radical ’60s lawyer William Kunstler; Beau Willimon’s contemporary Washington comedy THE PARISIAN WOMAN; UNTIL THE FLOOD, Dael Orlandersmith’s clear-eyed examination of the events in Ferguson, Missouri; RELATIVITY, Mark St. Germain’s play about a little-known event in the life of Einstein. But you’ll also find plays by very new playwrights, some of whom have never been published before: Jiréh Breon Holder’s TOO HEAVY FOR YOUR POCKET, set during the early years of the civil rights movement, shows the complexity of choosing to fight for one’s beliefs or protect one’s family; Chisa Hutchinson’s SOMEBODY’S DAUGHTER deals with the gendered differences and difficulties in coming of age as an Asian-American girl; Melinda Lopez’s MALA, a wry dramatic monologue from a woman with an aging parent; Caroline V. McGraw’s ULTIMATE BEAUTY BIBLE, about young women trying to navigate the urban jungle and their own self-worth while working in a billion-dollar industry founded on picking appearances apart. -

Catalogue1516.Pdf

Catalogue of New Plays 2015–2016 © 2015 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Once again, the Play Service is delighted to have all of this year’s Tony nominees for Best Play. The winner, Simon Stephens’ THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME, based on Mark Haddon’s best-selling novel, is a thrilling and emotional journey into the mind of an autistic boy. We acquired Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize- winning play DISGRACED after its run at Lincoln Center, and we are also publishing his plays THE WHO & THE WHAT and THE INVISIBLE HAND. Robert Askins’ subversive, hilarious play HAND TO GOD introduced this young American writer to Broadway, and the Play Service is happy to be his first publisher. Rounding out the nominess are Mike Poulton’s dazzling adaptations of Hilary Mantel’s WOLF HALL novels. THIS IS OUR YOUTH by Kenneth Lonergan and perennial favorite YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU by Kaufman and Hart were nominated for Best Revival of a Play. We have our 45th Pulitzer Prize winner in the moving, profane, and deeply human BETWEEN RIVERSIDE AND CRAZY, by Stephen Adly Guirgis, which is under option for Broadway production next season. Already slated for Broadway is Mike Bartlett’s “future history” play, KING CHARLES III, following its hugely successful production in the West End. Bess Wohl, a writer new to the Play Service, received the Drama Desk Sam Norkin Off-Broadway Award. We have her plays AMERICAN HERO and SMALL MOUTH SOUNDS. -

Inventory by Title

Inventory By Title Author Title Avner, Yehuda. The prime ministers Abbey, Barbara Complete book of knitting Abbott, Jeff. Panic Abbott, Tony. moon dragon, The Ablow, Keith Architect, the Active minds Trains Adams, Cindy Heller. Iron Rose Adams, Poppy, 1972- sister, The Addis, Don Great John L, the Adler, Elizabeth (Elizabeth A.) Please don't tell Agus, David, 1965- end of illness, The Aitkin, Don. Second chair, The Albert, Susan Wittig. Nightshade Albom, Mitch , 1958- , author. next person you meet in Heaven, The Albom, Mitch, 1958- First phone call from heaven Albom, Mitch, 1958- For One More Day Albom, Mitch, 1958- Have a little faith Albom, Mitch, 1958- Magic Strings of Frankie Presto, The Albom, Mitch, 1958- time keeper, The Albom, Mitch, 1958- Tuesdays with Morrie Albright, Jason et al A Day in the Desert Alcott, Kate Dressmaker, The Alcott, Kate. daring ladies of Lowell, The Alda, Arlene, 1933- Pig, horse, or cow, don't wake me now Alderman, Ellen. Right to Privacy, The Alder-Olsen, Jussi Keeper of Lost Causes, The Aldrich, Gary. Unlimited access Aldrin, Edwin E., 1930- Return to Earth Alexander, Eben. Proof of Heaven Alfonsi, Alice. New Kid in Town Aline, Countess of Romanones, 1923- Well-mannered Assassin, The Allen, Jonathan (Jonathan J. M.) , author. Shattered Allen, Sarah Addison. First Frost Allen, Sarah Addison. Sugar Queen, The Allen, Steve, 1921- Murder in Manhattan Allende, Isabel , author. In the Midst of Winter Allende, Isabel. sum of our days, The Allende, Isabel. Zorro Allgor, Catherine, 1958- Perfect Union, A Allison, Jay. This I believe II Amborse, Stephen E. Band of Bothers Ambrose, Stephen D-Day, June 6, 1944 Amburn, Ellis. -

The Little Madeleine the Autobiography of a Young Girl in Montmartre

1 09 047 TTWE LITTL.K Books by Mrs* Robert Hcwey LONDON THK UTTI,F, MAM-UIN!-' Pubthht'J hy . P, IHITTON A {.()., INC,, THE LITTLE MADELEINE THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A YOUNG GIRL IN MONTMARTRE by MRS. ROBERT HENREY t S T IH2 E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY, INC. New York, 1953 4- C:I M fm n* f, S. .\ 1 I- I U S I I It I T I O N f* f/*/,v h<*t*k nitty he w tt r in UHHAHY t>K <;ON<WK** CATAt.fK; C Allt> NUMHICH, 52-12157 This is the story of my girlhood. No fact has been altered. Rach character bears his, or her, own name. THE LITTLE MADELEINE WAS born on 1 3th August 1 906 in Montmartre in a steep cobbled street of leaning houses, slate-coloured and old, under the shining lofti- ness of the Sacr-Coeur, Matilda, my mother, describing to me later this uncommodious but picturesque corner which we left soon after my birth, stressed the curious characters from the Auvcrgne and from Brittany who kept modest cafts with zinc bars- Behind these they toiled, storing in dark courtyards or in windowless rooms coal, charcoal, and firewood dipped in resin, which the inhabitants of our street, who never had any money to spare, bought in the smallest quantities such as a pailful at a time* The Auvergnat traders in particular formed a clan of their own, each knowing from which village the others came, all speaking patois, and so unaccustomed to French that they mangled it when speaking and could only write their names. -

CHAN 9781(2) FRONT.Qxd 26/7/07 3:35 Pm Page 1

CHAN 9781(2) FRONT.qxd 26/7/07 3:35 pm Page 1 CHAN 9781(2) CHANDOS CHAN 9781 BOOK.qxd 26/7/07 3:39 pm Page 2 Courtesy of The Britten–Pears Library Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) Paul Bunyan An operetta in two acts and a prologue, Op. 17 Libretto by W.H. Auden The Royal Opera Production Directed for the stage by Francesca Zambello Recorded ‘live’ during performances at Sadler’s Wells Theatre ...........................................Pamela Helen Stephen mezzo-soprano Three Wild Geese (in the Prologue) ..................................................Leah-Marian Jones mezzo-soprano {........................................................................Lillian Watson soprano Narrator (in the Ballad Interludes) ..............................................................Peter Coleman-Wright baritone The Voice of Paul Bunyan ....................................................................................Kenneth Cranham speaker Johnny Inkslinger, bookkeeper ................................................................................................Kurt Streit tenor Tiny, Paul Bunyan’s daughter ........................................................................................Susan Gritton soprano Hot Biscuit Slim, a good cook ..................................................................................Timothy Robinson tenor Sam Sharkey ........................................................................................Francis Egerton tenor two bad cooks Ben Benny } {...................................................................................Graeme -

Professor Trina L. Goslin

Professor Trina L. Goslin English Language Fellow, US Department of State Emerita Professor, University of Nevada, Reno Intensive English Language Center Using vocabulary games to enrich your students’ critical thinking process SHARE VOCABULARY Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn. Chinese proverb How is vocabulary usually taught? LISTS and MEMORIZING This only activates short-term memory AS COMPARED TO COGNITIVE LEARNING: •21st Century Skills: •Adaptability •Complex communication skills •Non-routine problem solving •Self-management/self-development •Systems thinking A CRITICAL THINKER •Raises questions or problems and formulates them clearly •Uses abstract ideas to interpret relevant information •Comes to well-reasoned conclusions •Thinks open mindedly within alternative systems of thought •Communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions Can we expose our students to more effective vocabulary learning? LONG-TERM MEMORY SUGGESTIONS: •Match the words to synonyms, antonyms, or definitions •Creatively find association between words seemingly semantically unrelated •Work out the meaning of a word using the surrounding linguistic context Builds countless associations with other terms in the target language Brief 'hands on' activity-Playing "Apples to Apples" APPLES TO APPLES GAME How to play: •The first player-who is the judge-turns over the top green card and calls it out to the group. •Each other player lays down a red card to “match” the green card. •The judge mixes up the stack of cards and reads them to the group. •Other players have to orally defend their red card choices. •The judge decides who has the best match and gives the green card to the winner. -

SLATER SIGNALS the Newsletter of the USS SLATER's Volunteers by Timothy C

SLATER SIGNALS The Newsletter of the USS SLATER's Volunteers By Timothy C. Rizzuto, Executive Director Destroyer Escort Historical Museum USS Slater DE-766 PO Box 1926 Albany, NY 12201-1926 Phone (518) 431-1943, Fax 432-1123 Vol. 12 No. 12, December 2009 The struggle to preserve the SLATER takes many forms. Sometimes it takes the form of large groups of volunteers working together towards a common goal, like moving the ship, hauling the camels and hoisting the whaleboat. It takes the form of all of you who took the time to write all those checks to support the ship this winter. Other times it’s a battle of a lone individual, trying to make progress against overwhelming odds to accomplish a personal goal. Such is the case of Gary Sheedy on the reefer deck. A Google search of "Slater Signals," "Sheedy" and "Reefer Deck" shows us that Gary started the project back in January of 2001. Now for most of us, this would be a six-month project but, given Gary’s high standard of restoration, it didn’t look like he would ever finish. But this year, as autumn drew to a close, Gary felt like he was turning the corner and the end was finally in sight. All the bulkheads have been chipped and painted white. The deck has been chipped and painted red. All the pipe insulation has been repaired and painted white. The compressor bases are chipped and painted metallic silver gray and have been remounted. The first compressor has been restored to like new condition and remounted. -

Rich, Attractive People in Attractive Places Doing Attractive Things

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Rich, Attractive People In Attractive Places Doing Attractive Things Tonya Walker Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/992 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rich, Attractive People Doing Attractive Things in Attractive Places - A Monologue from Hell - - by Tonya Walker, Master of Fine Arts Candidate Major Director: Tom De Haven, Professor, Department of English Acknowledgement This thesis could not have been completed - completed in the loosest sense of the word - had in not been for the time and involvement of three men. I'd like to thank my mentor David Robbins for his unfailing and passionate disregard of my failings as a writer, my thesis director Tom De Haven for his patient support and stellar suggestions that are easily the best in the book and my husband Philip whose passionate disregard of my failings and patient support are simply the best. Abstract RICH, ATTRACTIVE PEOPLE IN ATTRACTIVE PLACES DOING ATTRACTIVE THINGS By Tonya Walker, M.F.A. A these submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 Major Director: Tom De Haven, Professor, Department of English Rich, Attractive People in Attractive Places Doing Attractive Things is a fictional memoir of a dead Manhattan socialite from the 1950's named Sunny Marcus.