Little Red Cap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Liberation of the Heroine in Red Riding Hood : a Study on Feminist and Postfeminist Discourses

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of English 2-11-2015 The liberation of the heroine in Red Riding Hood : a study on feminist and postfeminist discourses Hiu Yan CHENG Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cheng, H. Y. (2015). The liberation of the heroine in Red Riding Hood: A study on feminist and postfeminist discourses (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/eng_etd/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE LIBERATION OF THE HEROINE IN RED RIDING HOOD: A STUDY ON FEMINIST AND POSTFEMINIST DISCOURSES CHENG Hiu Yan MPHIL Lingnan University 2015 THE LIBERATION OF THE HEROINE IN RED RIDING HOOD: A STUDY ON FEMINIST AND POSTFEMINIST DISCOURSES by CHENG Hiu Yan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in English Lingnan University 2015 ABSTRACT The Liberation of the Heroine in Red Riding Hood: a Study on Feminist and Postfeminist Discourses by CHENG Hiu Yan Master of Philosophy Fairy tales’ magic is powerful because it has the potential to enter different cultures at different times. -

Corvus Review

CORVUS REVIEW WINTER 2016 ISSUE 4W 2 Letter from the Editor Welcome to 4W! It seems this little lit journal has really grown and turned into something quite fantastic. I’m very excited to present the work within this issue and genuinely hope you enjoy reading through. In terms of quality, I think this collection is of high caliber and the artists contained within these pages are truly talented individuals, the sort of work I hope you’ve come to expect from Corvus. Over the last little while, Corvus has achieved several milestones. We’re listed on Duotrope.com and NewPages.com. We’ve also hit over 1300 followers on Twitter and connected with many other little lit journals, talented editorial staff members, and contributors. We’ve also gained the attention of the Facebook community via our Facebook page. In short, it’s been both wonderful and rewarding to see this journal grow and develop, thanks primarily to our contributors and charitable donors. Corvus has also begun to offer writing services through Corvid Editing Services. Pop by www.corev.ink for more info. Thank you all so much for your commitment to Corvus and I look forward to making every issue as great (or greater) than the last. Happy Scribbling! Janine Mercer EIC, Corvus Review Table of Contents Poetry Prose Bella 4 Reeves-Murray 27-28 Stout 5 Half Pillow 29-35 Dougherty 6-7 Rowe 36 Kwalton 8 Pipher 37-39 Howerton 9 Lamberty 40-45 Vaccaro Nelkin 10 Grey 12-14 Tu 46-51 Miles 15 Geigley 52-58 Jacobs 16 Heger 59-64 Webb 17 Charpentier 65-68 Boggess 18 Sullivan 69-71 Mize 19 Mulhern 72-76 Johnson 20 Lynn 21-23 Price 77-86 Petras 24-25 Belle 87-90 Huffman 26 Schumacher 91 Mc Ivor 93-97 Hendrickson 98-100 Easton 101-106 Racklin 107-108 Hinton 109-113 Cover/Editors Bio 114 Chiasmus Lana Bella You no longer feel the urge to slam the door, instead, with a casual flick of your fingers, you set them loose, groaning toward their final berth. -

Ever Since Humans Gained the Ability of Higher Thought People Have Been Creating and Telling Stories

English 12 Final Essay Choice 1 Ever since humans gained the ability of higher thought people have been creating and telling stories. These stories are passed on from one generation to the next and at some point become more than stories; they become tradition, culture, and history. Long after the original writers or creators of the stories are dead and all but forgotten, the stories remain and become a legacy. With each year that passes by the stories grow, they are modified or retold a different way, and as they grow those stories become more rooted in the cultures of those who share them. Fairytales are some of the most widespread and evident stories in cultures; they manage to catch the interest of almost all readers, and have grown far more than the average story. One such beloved fairytale is “Little Red Riding Hood,” which has seen many different authors and titles throughout its existence. The story of Little Red Riding Hood began as tales told to children, passed on through word of mouth alone. The first written version, which has come to represent the oldest and original story, was “Little Red Riding Hood” by Charles Perrault. The tale followed the characteristics of all fairytales; a handful of characters, a simple and short storyline, and a lesson to be learned. The characters were: a young and pretty girl known only as Little Red Riding Hood, a wolf that had the ability to speak, and an old and sickly grandmother of Red. The tale mentioned Red’s mother and woodsmen briefly, but their only purpose was to guide the story, they did not significantly interact within the story. -

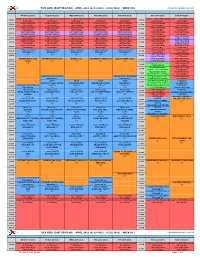

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

The Goldfish and Little Red Riding Hood: Characters and Their Combinations in Fairy Tale Jokes and Parodies*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 13 (1): 9–28 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2019-0002 THE GOLDFISH AND LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD: CHARACTERS AND THEIR COMBINATIONS IN FAIRY TALE JOKES AND PARODIES* RISTO JÄRV Head of the Archives, PhD Estonian Folklore Archives, Estonian Literary Museum Vanemuise 42, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT There are two types of joke that can be described as fairy tale jokes: those with punchlines that include fairy tale characters, and fairy tale parodies. The paper discusses fairy tale jokes that were sent to the jokes page of the major Estonian internet Web Portal Delfi by Internet users between 2000 and 2011, and jokes added by the editors of the portal between 2011 and 2018 (CFTJ). The joke corpus has had different addresses at different times, and was a live ‘folklore field’ for the first few years after creation. Of all the characters, the Goldfish appeared in the largest number of jokes (76 out of a total of 286 jokes), followed by Little Red Riding Hood (72). Other fairy tale characters feature in a 14 or fewer fairy tale jokes each. Several fairy tale jokes circulating on the Internet varied over the period observed. Fairy tale jokes generally get their impetus from the characters and from plots with unexpected outcomes. A seemingly innocent fairy tale character is often linked to a sexual theme: sexuality holds first place as the source of humour in fairy tale jokes, although this may be caused by the so-called genre code of jokes. KEYWORDS: fairy tale joke • fairy tale • joke • interpretation • parody Fairy tale characters are often iconic and need no explanation; they are likely to evoke associations with the full content of the tale and its web of relations in most people in the Western cultural sphere. -

Little Red Riding Hood

CONTEXTUALIZE - Written by Scottish poet Carol Ann Duffy - It is the first poem in her 1999 anthology The World's Wife, which subverts myths and fairytales in order to re-examine and play with traditional narratives that exist within them, particularly when it comes to gender roles. - subverts the original Brother Grimm’s fairytale Little Red Riding Hood. Though usually portrayed as a naive girl ultimately eaten by a wolf, Duffy's Little Red Cap is a young woman brimming with sexual curiosity and personal agency. Her relationship with the wolf, though marked by a predatory power imbalance, serves as the catalyst for her coming-of-age. - The content of this poem can be seen as a reflection of Duffy’s own experiences with her Adrian Henri who she was in a relationship with despite their large age gap. In this sense, this poem can be seen as having an autobiographical element. OVERVIEW - The poem is telling the story of the female persona who transitions from childhood to adulthood and spots a wolf, who she gets into a relationship with. However, over time the female persona gains her poetic and sexual independence and slowly outgrows the wolf. Ultimately, the female persona kills the wolf (which has both a literal and metaphorical significance) and is able to walk away from her relationship as an independent woman. - The poem is highly symbolic, with the wolf representing male power, and Red Cap representing the transformation of a girl to young adulthood and sexual awakening. NARRATION - Narrated from a first-person perspective instead of a 3rd person omniscient as is the case with the original story. -

Carol Ann Duffy's Postmodern Satire

MIXING GENRES AND GENDERS: CAROL ANN DUFFY’S POSTMODERN SATIRE: THE WORLD’S 1 WIFE Pilar Abad University of Valladolid INTRODUCTION The editors of the 1993 anthology entitled The New Poetry define the latter as a kind of poetry “… that is fresh in its attitudes, risk-taking in its address, and plural in its forms and voices…” (Hulse, Kennedy & Morley 1993:16). Most of this poetry is written by poets who, at the time, were officially appointed as New Gen Poets,2 and seven years later (2001) are considered solid assets,3 an appreciation which comes down to our day. Some of them were eight women- poets whose poetry has been summed up as “… moving, entertaining, technically innovative, often brilliant…”(Dunmore 1995) and among them is the one who will be the focus of attention in this exposé: Carol Ann Duffy (1955-). I have chosen Carol Ann Duffy as my subject as, undoubtedly, today’s most widely acclaimed mainstream British woman-poet: “… The figurehead of New Generation … Carol Ann has vindicated the faith people had in her then by becoming an indisputable popular poet alongside Heaney. The poet’s poet in 1994, she is quite clearly now the People’s (poet)…” (Forbes 2001:22). In 1999 she was candidate for the Laureate Poet’s throne (after Heaney’s resignation) and undeservedly relegated (in favour of Andrew Motion) mainly for political 1 Conferencia pronunciada en el XXVIII Congreso internacional AEDEAN. 2 See Longley, “How We Made the New Generation” (1994): 52-53; Forbes, “Talking About the New Generation” (1994): 4-6. -

Little Red Cap by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

Little Red Cap by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm Once upon a time there was a sweet little girl. Everyone who saw her liked her, but most of all her grandmother, who did not know what to give the child next. Once she gave her a little cap made of red velvet. Because it suited her so well, and she wanted to wear it all the time, she came to be known as Little Red Cap. One day her mother said to her, “Come Little Red Cap. Here is a piece of cake and a bottle of wine. Take them to your grandmother. She is sick and weak, and they will do her well. Mind your manners and give her my greet- ings. Behave yourself on the way, and do not leave the path, or you might fall down and break the glass, and then there will be nothing for your sick grand- mother.” Little Red Cap promised to obey her mother. The grandmother lived out in the woods, a half hour from the village. When Little Red Cap entered the woods a wolf came up to her. She did not know what a wicked animal he was, and was not afraid of him. “Good day to you, Little Red Cap.” “Thank you, wolf.” “Where are you going so early, Little Red Cap?” “To grandmother’s.” “And what are you carrying under your apron?” “Grandmother is sick and weak, and I am taking her some cake and wine. We baked yesterday, and they should give her strength.” “Little Red Cap, just where does your grandmother live?” “Her house is a good quarter hour from here in the woods, under the three large oak trees. -

Yabla German Lessons with Links to Videos Containing Examples Two

Yabla_German_Lessons 4/27/15 2:18 PM Yabla German Lessons with links to videos containing examples Two-way Prepositions Most commonly spoken German prepositions take the accusative or dative case (the genitive case is used more often in the written form). Some prepositions, such as bis, durch, für, gegen, je, ohne, um and wider, take only the accusative case. Others, like aus, außer, bei, gegenüber, mit, nach, seit, von and zu, take only the dative case. There are, however, certain prepositions that can take either the accusative or the dative case, depending on the context: an, auf, hinter, in, neben, über, unter, vor and zwischen. Even experienced German speakers can get it wrong sometimes, so although you've probably learned this before, this may be a good time to review these two-way (or dual) prepositions. The general rule to remember: if the preposition is dealing with "where" something is in a static sense, it takes the dative case; if it is dealing with motion or destination ("where to" or "what about") in an active sense, then it takes the accusative case. Der Spiegel hängt an der Wand. The mirror is hanging on the wall. Caption 34, Deutschkurs in Tübingen: Mehr Wechselpräpositionen Since the wall is where the mirror is statically hanging, the feminine noun die Wand takes the dative case in this context. Sie gehen an die Arbeit wieder. They're going to work again. Caption 29, Der Struwwelpeter: Hans Guck-in-die-Luft Since work is where they are actively going to, the feminine noun die Arbeit takes the accusative case. -

“Little Red Riding Hood” by Charles Perrault

Charles Perrault, “Little Red Riding Hood” (1697) Transl. Andrew Lang (1889) Perrault (1623 - 1708 ) was a French writer and government functionary who late in life published a collection of folktales, written for his children and drawn from pre-existing stories but heavily reworked by him; among the collection are such classics as “Sleeping Beauty,” “Puss in Boots,” and “Cinderella.” Andrew Lang (1844 – 1912) was a Scottish folklorist, writer, historian, translator, and poet now known primarily for his own folk tales. Once upon a time there lived in a certain village a little country girl, the prettiest creature who was ever seen. Her mother was excessively fond of her; and her grandmother doted on her still more. This good woman had a little red riding hood made for her. It suited the girl so extremely well that everybody called her Little Red Riding Hood. One day her mother, having made some cakes, said to her, "Go, my dear, and see how your grandmother is doing, for I hear she has been very ill. Take her a cake, and this little pot of butter." Little Red Riding Hood set out immediately to go to her grandmother, who lived in another village. As she was going through the wood, she met with a wolf, who had a very great mind to eat her up, but he dared not, because of some woodcutters working nearby in the forest. He asked her where she was going. The poor child, who did not know that it was dangerous to stay and talk to a wolf, said to him, "I am going to see my grandmother and carry her a cake and a little pot of butter from my mother." "Does she live far off?" said the wolf "Oh I say," answered Little Red Riding Hood; "it is beyond that mill you see there, at the first house in the village." "Well," said the wolf, "and I'll go and see her too. -

Little Red Riding Hood Annotations.Pdf

1. Red: Scarlet or red is a sexually vibrant and suggestive color. At one time, it was not worn by morally upright women thanks to its sinful symbolism. It is also the color of blood with all of its connotations. Perrault introduced the color red to the tale when he first wrote it. ! 2. Little Red Riding Hood: The red riding hood is a popular and familiar symbol to much of Europe and North America. In the height of portraiture in the nineteenth century, many young daughters of wealthy families were painted wearing red capes or hoods. Today, some little girls still want to wear red capes for Halloween or other imaginative play. 3. Go, my dear, and see how your grandmother is doing: In Charles Perrault's version of the tale, the mother simply instructs the young girl to take the items to her grandmother. The Grimms, however, added an admonition from the mother to not stray from the path, adding a moral message to children. Perrault adds the moral to "not talk to strangers" at the end of the tale. Through the moralizing of both Perrault and Grimms', critics explain that the tale moved away from its obvious sexual and horrific tones, to more closely resemble a fable or cautionary tale (Tatar 1992). You can read the Grimms' version here: Little Red Cap.! 4. Cake, and this little pot of butter: These are the food items originally described by Charles Perrault. Later versions have included other food items, most often a bottle of wine. ! 5. Wolf: The wolf has become a popular image in fairy tales thanks to this tale and The Tale of the Three Little Pigs. -

"Little Red Riding Hood" Exists in Many Its Anxiety-Producing E Different Versions

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. THE USES OF ENCHANTMENT 166 "Little Red Riding H bined efforts. These stories direct the child toward transcending his But the literary h immature dependence on his parents and reaching the next higher his title, "Little Re stage of development: cherishing also the support of age mates. Coop- English, though the erating with them in meeting life's tasks will eventually have to re- Red Cap," is more ; place the child's single-minded reliance on his parents only. The child most erudite and a of school age often cannot yet believe that he ever will be able to meet variants of "Little I the world without his parents; that is why he wishes to hold on to them cluded his, we migk beyond the necessary point. He needs to learn to trust that someday been its fate if the B he will master the dangers of the world, even in the exaggerated form of the most popula: in which his fears depict them, and be enriched by it. starts with Perrauli The child views existential dangers not objectively, but fantastically first. exaggerated in line with his immature dread-for example, per- Perrault's story 1: sonified as a child-devouring witch. "Hansel and Gretel" encourages how the grandmoth the child to explore on his own even the figments of his anxious hood (or cap), whicl imagination, because such fairy tales give him confidence that he can day her mother ser master not only the real dangers which his parents told him about, but grandmother, who even those vastly exaggerated ones which he fears exist.