Corvus Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Little Red Cap

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Little Red Cap filled with enticing books. She is filled with intense pleasure and SUMMARY excitement upon seeing all these books, her response to reading so many words described in terms resembling an As the speaker leaves behind the metaphorical neighborhood orgasm. of her childhood, there are fewer and fewer houses around, and the landscape eventually gives way to athletic fields, a local Time passes, however, and the speaker reflects on what ten factory, and garden plots, tended to by married men with the years together with the wolf has taught her. She compares the same submissive care they might show a mistress. The speaker oppressive nature of their relationship to a mushroom growing passes an abandoned railroad track and the temporary home of from, and thus figuratively choking, the mouth of a dead body. a recluse, before finally reaching the border between her She has learned that birds—implied to be representative of neighborhood and the woods. This is where she first notices poetry or art in general—and the thoughts spoken aloud by someone she calls "the wolf." trees (meaning, perhaps, that art comes only from experience). And she has also realized that she has become disenchanted He is easy to spot, standing in a clearing in the woods and with the wolf, both sexually and artistically, since he and his art proudly reading his own poetry out loud in a confident oice.v have grown old, repetitious, and uninspiring. The speaker notes the wolf's literary expertise, masculinity, and maturity—suggested by the book he holds in his large hands The speaker picks up an axe and attacks a willow tree and a fish, and by his thick beard stained with red wine. -

January 2021 Newsletter Volume 6, Number 1

The Eyes of the Golden Hall ~ A Newsletter of The Center for Human Awakening ~ January 2021 Newsletter Volume 6, Number 1 In this e-Newsletter… FROM THE EDITOR’s HEART............................................................................................................................ 3 THEMED ARTICLES ............................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Therapy—The Strangest Pursuit, by Richard Harvey ..................................................................................... 4 2. Allow Things To Go Where They Need To Go, by Robert Meagher ............................................................. 6 3. Letting Go Of Everything, by Richard Harvey ............................................................................................... 8 4. Just Let It All Go, by Robert Meagher .......................................................................................................... 11 5. God Will Disappear And You Will Remain, by Richard Harvey ................................................................. 13 6. Letting Go And Trusting, by Robert Meagher .............................................................................................. 15 7. Letting Go And Non-Attachment, by Richard Harvey .................................................................................. 17 8. Letting Go Of The Last Vestiges Of The World As I Know It, by Robert Meagher .................................... 21 9. The Consciousness -

Georgian Court University Spring 2018 Magazine

Volume 15 | Number 2 Spring 2018 Georgian Court University Magazine #WhyImRunning GCU Women Run for Office From the President Dear Alumni, Donors, Students, and Friends: One of the best things about spring is that it brings us a sense of renewal and promise. Winter is finally behind us, there are lots of fun holidays and family gatherings to look forward to, and at Georgian Court, Commencement is right around the corner. This spring edition of GCU Magazine, our first since 2012, is a window into the promise and the pride that we feel at Georgian Court. It shows in the feature about the dedication of our School of Education alumni and students (p. 10), including GCU senior Jess Singer, who’s now a teacher intern in the classroom of her high school art teacher, Bobbi Allaire ’84, ’07. We trust you will be proud to read about Thomas DiPaolo ’12, who rearranged his Disney World wedding plans (p. 32) to include his ailing father living at a local nursing home. His story of compassion, a Mercy core value, made headlines and went viral. We believe the story of Jessica Franklin ’17, a recent nursing graduate who put her skills to use as a volunteer in India and Tanzania (p. 16), will resonate with you as well. Plus, the core value of service is also seen in the work of the GCU Lions men’s soccer team (p. 30), which has helped needy families through Vincent’s Legacy, and in the many examples of service you will find in our Endnote. -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23

ページ:1/37 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-9896-0141 JASRAC IT'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9456-6173 JASRAC LIFE ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-6164-2103 JASRAC Little Hero ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-8964-6568 JASRAC Music Is My Life ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3920-1425 JASRAC MY FRIEND 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-4568-5680 JASRAC ONE ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-5012-2991 JASRAC One Love ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-7840-5002 JASRAC So Special -Version AI- ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4160-4608 JASRAC アシタノヒカリ ISUM-0692-2103 JASRAC sogood ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-5944-4115 NexTone ココア by MisaChia ISUM-1020-1708 JASRAC Story ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-7456-6568 NexTone さよならの前に ISUM-2432-5002 JASRAC Story(English Version) 369 AAA ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-3344-2596 NexTone ハレルヤ ISUM-9864-0141 JASRAC VOICE ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-7328-6173 NexTone ハレルヤ -Bonus Tracks- ISUM-1256-5286 JASRAC WA Interlude feat.鼓童,Jinmenusagi AI ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-7296-2102 JASRAC ぼくの憂鬱と不機嫌な彼女 ISUM-9404-0536 JASRAC Wonderful World feat.姫神 ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia -

2019 Session 1 Chapbook

“If I’m not for myself, who will be for me? If I’m only for myself, what am I? And if not Creative Writing now, then when?” Chapbook – Pirkei Avot Session One 2019 CONTENTS Notes from the Editor “The Narrators of Life” by Benjamin B. 3 This summer, 6 Points Creative Arts Academy added a creative writing “Wongarts” by Becca N. 7 major comprised of passionate wordsmiths from both Bonim and Olim. These majors constructed narrative works, exploring dialogue, exposition, “The Death Dance” by Naomi J. 10 and scene, before crafting their final pieces all of which centered around the theme of the summer, which comes from Pirkei Avot: “If I am not for “Nine Lives” by Natanya D. 15 myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, then when?” In a minor titled: Adapting Stories, campers from a “Time” by Rebecca B. 17 variety of majors came together to read, write, and create fractured fairy tales and Torah stories. Some of those stories are included in this chapbook. “The Butterfly Room” by Olivia S. 20 “Speechless” by Sunny C. 23 Creative Writing Arts Mentor: Carly Husick “Beaut-evil” by Hanna P. 24 Instructors: Allison Woitte “The Art of Trying” by Maya F. 29 Noy Israeli Tani Prell Epstein “The Ransacking” by Charlie R. 32 Abe Frankel “The Man of Iron” by Jonathon N. 34 Artistic Director: David Loewy “The Lady and the Beast” by Ciera and Sophia 36 “Grandmother” by Isabel, Hannah, and Brandon 38 “Theadora” by Ellis S. -

Chapter-1 Gee As You

Gee You Are You Gee You Are You Krishna Prem (Michael Mogul) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2011 by Michael Mogul (Krishna Prem) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review. Printed in the United States of America First Printing: July, 2011 ISBN-978-1-61364-318-1 About the Author Gee You Are You is a book about a life’s journey from here to here. On the front cover is a picture of me at thirty-three years of age, sitting on a cold marble floor in front of my teacher and friend, Osho, in Pune, India. On the back cover I am the ripe old age of sixty-six. As Bob Dylan once sang, “Oh, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.” Yes, my body is now twice as old and yet I feel half my age… the magic of meditation. Through my years of peeling the layers of my own onion, I have turned my life from maditation in the outer world to meditation in my inner world. While reading this book, you will be constantly challenged to witness that you are not so much your conditioning in the marketplace of your hometown, but more that the world is appearing in you… that you are not the mind. -

GEERDES Midimusic Katalog

10 - A*T 26.02.2006 Publisher 0-9 2PAC 50 Cent :Olivia GEERDES midimusic e.K. 5715 California Love........................... T 26472 * Candy Shop............................... K 10 CC 11809 * Changes.................................... K Lauterstr. 17-18 12547 * Dear Mama............................... T 5000 Volt 12159 Berlin 1914 * Dreadlock Holiday..................... K 26625 * Ghetto Gospel............................ K Germany 2460 * I'm Not In Love.......................... K 19542 * Until The End of Time................ K 7673 * I'm On Fire................................ K 17187 * Rubber Bullets........................... K Web: www.geerdes.de 16998 * The Things We Do For Love......... K 2PAC & The Outlawz 504 Boyz Email: [email protected] 14256 * Baby Don't Cry (Keep Ya )........... K 14650 * Wobble Wobble......................... K Phone: ++49 +30 850 74 64 0 112 Fax: ++49 +30 850 74 64 1 18245 * It's Over Now............................. K 2PAC :Notorious B.I.G. 5th Dimension 19396 * Peaches And Cream................... K 10349 * Runnin'..................................... T 11237 * Up Up And Away....................... T Graphic & Layout: Raoul Hübner 112 :Lil'Z 3 Degrees 666 12364 * Anywhere.................................. K Contents 11226 * When Will I See You Again......... K 8925 * Alarma!.................................... T 9355 * Diablo...................................... T 113 This catalog contains only MIDI and 3 Doors Down 14661 * Tonton du bled.......................... K 702 KARAOKE files of the interprets. -

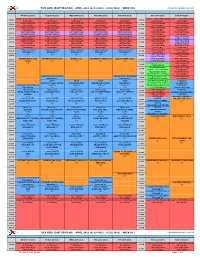

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Tues June 20 Membership Campaign June 1-11

June 2017 This Summer, PBS brings you the world THE EXPEDITION BEGINS Tues June 20 Membership Campaign June 1-11 5.1 • 5.2 • 5.3 • knpb.org • 775.784.4555 2 June 2017 The KNPB 7 Winners knpb.org/writerscontest 1st Place “The Sun Hat” by Ryver – Jessie Beck Elementary School 2nd Place “If Dinosaurs Came to My House” by Elise – Verdi Elementary School K 3rd Place “American Symbols” by Kylee – Spanish Springs Elementary School 1st Place “The Boy Who Wanted to Be a Champ” by Zachary st – Nancy Gomes Elementary School 2nd Place “Bear on a Magic Carpet” by Carson – Jessie Beck Elementary School grade1 3rd Place “Kittens at Night” by Camdyn – Lena Juniper Elementary School 1st Place “Ben and the Bully” by Alec – Our Lady of the Snows School nd 2nd Place “The Penguin Who Almost Got Eaten” by Camila 2grade – Grace Warner Elementary School 3rd Place “My Hedgehog” by Ellie – Peavine Elementary School 1st Place “Food Fiesta” by Gracie – Hidden Valley Elementary School 2nd Place “A Turkey Named Wilbur” by Savannah rd 3 – Nancy Gomes Elementary School grade 3rd Place “Princess Panolia’s Tangled Hair” by Meridian – Jessie Beck Elementary School SPONSORED LOCALLY BY With support from Lemelson Foundation, Nell J Redfield Foundation, Hall Family Charitable Fund, Marie Crowley Foundation, Abraham & Sonia Rochlin Foundation, Anonymous Donor, Thelma B. & Thomas P. Hart Foundation, Jack Van Sickle, Western Nevada Supply, University of Nevada, Reno – Pack Internship Grant Program Meetings of the KNPB Board of Trustees, Board Committees and the Community Advisory Board are held at the KNPB offices at 1670 N. -

March 2017 Primetime Listings – 57.1 Mountain Lake PBS

March 2017 Primetime Listings – 57.1 Mountain Lake PBS WEDNESDAY, March 1, 2017 In this program, award winning psychiatrist, brain-imaging expert and 10-time New York Times bestselling author Dr. Daniel Amen and 8:00 PM SPY IN THE WILD, A NATURE MINISERIES: MEET THE SPIES his wife Tana Amen, also a New York Times bestselling author and The final "making of" episode takes us through the evolution of Spy nurse, will give you 50 ways to grow your brain and their best Creatures from the original BoulderCam to the PenguinCams that secrets to ignite your energy and focus at any age. (Repeats 3/4 at inspired the "spycams" in this series. Marvel and laugh at 2:00am, 3/8 at 12:30am, 3/11 at 2:00pm and 3/17 at noon) unexpected and funny moments from the Spy Creatures' POV. (Repeats 3/2 at 1:00am and 3/3 at noon) 11:00 PM BBC WORLD NEWS 9:00 PM AFRICA'S GREAT CIVILIZATIONS: THE ATLANTIC 11:30 PM CHARLIE ROSE AGE/COMMERCE AND THE CLASH OF CIVILIZATIONS - D Empires of Gold - Henry Louis Gates, Jr. uncovers the complex trade 12:30 AM TAVIS SMILEY networks and advanced educational institutions that transformed early north and west Africa from deserted lands into the continent's SATURDAY, March 4, 2017 wealthiest kingdoms and learning centers. Cities - Gates explores the power of Africa's greatest ancient cities, including Kilwa, Great 8:30 PM ROCK REWIND 1967-1969 (MY MUSIC) - P Zimbabwe and Benin City, whose wealth, art and industry successes Take a time-tripping visit to the psychedelic era with host Tommy attracted new European interest and interaction along the James. -

Sophie's World

Sophie’s World Jostien Gaarder Reviews: More praise for the international bestseller that has become “Europe’s oddball literary sensation of the decade” (New York Newsday) “A page-turner.” —Entertainment Weekly “First, think of a beginner’s guide to philosophy, written by a schoolteacher ... Next, imagine a fantasy novel— something like a modern-day version of Through the Looking Glass. Meld these disparate genres, and what do you get? Well, what you get is an improbable international bestseller ... a runaway hit... [a] tour deforce.” —Time “Compelling.” —Los Angeles Times “Its depth of learning, its intelligence and its totally original conception give it enormous magnetic appeal ... To be fully human, and to feel our continuity with 3,000 years of philosophical inquiry, we need to put ourselves in Sophie’s world.” —Boston Sunday Globe “Involving and often humorous.” —USA Today “In the adroit hands of Jostein Gaarder, the whole sweep of three millennia of Western philosophy is rendered as lively as a gossip column ... Literary sorcery of the first rank.” —Fort Worth Star-Telegram “A comprehensive history of Western philosophy as recounted to a 14-year-old Norwegian schoolgirl... The book will serve as a first-rate introduction to anyone who never took an introductory philosophy course, and as a pleasant refresher for those who have and have forgotten most of it... [Sophie’s mother] is a marvelous comic foil.” —Newsweek “Terrifically entertaining and imaginative ... I’ll read Sophie’s World again.” — Daily Mail “What is admirable in the novel is the utter unpretentious-ness of the philosophical lessons, the plain and workmanlike prose which manages to deliver Western philosophy in accounts that are crystal clear. -

Gundam 00 Trust You Full Mp3 Download

Gundam 00 Trust You Full Mp3 Download Gundam 00 Trust You Full Mp3 Download 1 / 2 Now we recommend you to Download first result Hd機動戰士鋼彈00 Mobile Suit Gundam 00 Ed4 伊藤由奈 Trust You中日字幕 MP3 which is .... 05:20. 【HD】機動戰士鋼彈00 Mobile Suit Gundam 00 ED4 - 伊藤由奈 - trust you【中日字幕】. 4.55 M+. Play Music. Stop Music. Download MP3. Ringtone. 05:43 .... The title song, "Trust You" is the theme to Japanese anime Mobile Suit Gundam 00 season 2, while "Brand New World" was used as a tie-up song for the .... 09, trust you, 5:21. 10, Unlimited Sky, 3:15. 11, TOMORROW, 5:29. 12, CHANGE, 3:51. 13, 閉ざされた世界, 4:53. 14, もう何も怖くない、怖くはない .... 03 - Koi wa groovy x2.mp3 다운로드, 8676k, 버전 1, 2012. 7. 11. 오후 11:40, 업로더. Ć. 04 - trust you -Gundam 00 Version-.mp3 다운로드, 3616k, 버전 1, 2012. 7.. Gundam 00 Season 2 - Trust You - Yuna Ito | Nghe nhạc hay online mới nhất chất lượng cao. ... bạn có thể nghe, download (tải nhạc) bài hát gundam 00 season 2 - trust you mp3, playlist/album ... Mobile Suit Gundam 00 Complete Best (2009).. This article lists the albums attributed to the series Mobile Suit Gundam 00. ... Trust You; Brand New World; Koi wa Groovy×2 -DJ-PASSION MORE ... Single of Mobile Suit Gundam 00 first season's insert song, used in episode 19 and 24.. Download das Músicas (mp3) de Gundam 00 Second Season em Link Direto e mais downloads ... Trust You (ED3 TV Size), Yuna Ito, 1.4 MB, 1:31, 439, Baixe!.