Reader's Report: Asbjørn Jaklin: the Narvik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ski Touring in the Narvik Region

SKI TOURING IN THE NARVIK REGION TOP 5 © Mattias Fredriksson © Mattias Narvik is a town of 14 000 people situated in Nordland county in northern Norway, close to the Lofoten islands. It is also a region that serves as an excellent base for alpine ski touring and off-piste skiing. Here, you are surrounded by fjords, islands, deep valleys, pristine lakes, waterfalls, glaciers and mountain plateaus. But, first and foremost, wild and rugged mountains in seemingly endless terrain. Imagine standing on one of those Arctic peaks admiring the view just before you cruise down on your skis to the fjord side. WHY SKI TOURING IN THE NARVIK REGION? • A great variety in mountain landscapes, from the fjords in coastal Norway to the high mountain plateaus in Swedish Lapland. • Close to 100 high quality ski touring peaks within a one- hour drive from Narvik city centre. • Large climate variations within short distances, which improves the chances of finding good snow and weather. • A ski touring season that stretches from the polar night with its northern lights, to the late spring with never- ending days under the midnight sun. • Ascents and descents up to 1700 metres in vertical distance. • Some of the best chute skiing in the world, including 1200-metre descents straight down to the fjord. • Possibilities to do train accessed ski touring. • A comprehensive system of huts that can be used for hut-to-hut ski touring or as base camps. • 5 alpine skiing resorts within a one-hour car drive or train ride • The most recognised heli-skiing enterprise in Scandinavia, offering access to over 200 summits. -

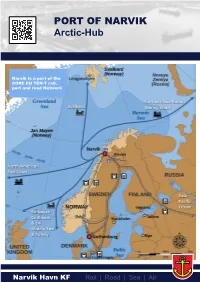

PORT of NARVIK Arctic-Hub

PORT OF NARVIK Arctic-Hub Narvik is a part of the CORE EU TEN-T rail, port and road Network 1 Arctic-Hub The geographic location of Narvik as a hub/transit port is strategically excellent in order to move goods to and from the region (north/south and east/west) as well as within the region itself. The port of Narvik is incorporated in EU’s TEN-T CORE NETWORK. On-dock rail connects with the international railway network through Sweden for transport south and to the European continent, as well as through Finland for markets in Russia and China. Narvik is the largest port in the Barents Region and an important maritime town in terms of tonnage. Important for the region Sea/port Narvik’s location, in relation to the railway, road, sea and airport, Ice-free, deep sea port which connects all other modes of makes the Port of Narvik a natural logistics intersection. transport and the main fairway for shipping. Rail Airport: The port of Narvik operates as a hub for goods transported by Harstad/Narvik Airport, Evenes is the largest airport in North- rail (Ofotbanen) to this region. There are 19 cargo trains, in ern Norway and is one of only two wide body airports north each direction (north/south), moving weekly between Oslo and of Trondheim. Current driving time 1 hour, however when the Narvik. Transportation time 27 hours with the possibility of Hålogaland Bridge opens in 2017, driving time will be reduced making connections to Stavanger and Bergen. to 40 minutes. The heavy haul railway between Kiruna and Narvik transports There are several daily direct flights from Evenes to Oslo, 20 mt of iron ore per year (2015). -

Militære Veivalg 1940- 45 En Undersøkelse Av De Øverste Norske Militære Sj Efers Valg Mellom Motstand Og Samarbeid Under Okkupasjonen 1

Kapittel8 Militære veivalg 1940- 45 En undersøkelse av de øverste norske militære sj efers valg mellom motstand og samarbeid under okkupasjonen 1 Lars Borgersrud2 Under en samtale tillot jeg meg å spørre ham so m gammel kamerat: «Er det fo r sent å gå sammen med Tyskl and mot England?>> Spørsmålet var uttrykk fo r mitt syn på hvordan utviklingen burde vært. Kon torsjefi Forsvarsdepartementet, major F.H Kjelstrup, 3 til statsråd B. Ljungberg 9· april I940 Mange nordmenn deltok i motstandskampen 1940-45, særlig på slutten av krigen. D et var annerledes i begynnelsen. Kri gslitteraturen gir inn trykk av at særlig offiserene var aktive, og at motstandskampen for deres del var en fortsettelse av felttoget i 1940. Men ser vi nærmere på motstanden i det okkuperte Norge, og særlig i den første tiden, så er førstei nntrykket et helt annet. Vi treffer på sjøfolk, arbeidere og funksjonærer innen transport og industri, håndverkere, 1 Militære veivalg 194D-1945er basen på en seminarrappon som ble present en ved lnstitun for sammen liknende poli tikk, Unive rsitetet i Bergen, 23.3· 98. 2 Lars Borgersrud, dr. philos . (Universitetet i Oslo 1995), har skrevet bl. a. Nødvendig innsats, 1997, Wol!weberorganisasjonen i Norge, 1995, Unngå å irritere fienden, 1981, og væ n bidragsyte r og redak sjonsko nsulent i N onk krigsleksikon 194D-1945 (Oslo 1995) Fra et samtidig manuskript som ble funnet i NS' arkiver av kaptein i FO 2 , Finn Nagell, og oversendt generalmajor Halvor Hansson i Forsvarets O verkommando 13. 12. 4 5· Han sendte den videre til Undersøkelseskommisjonen av 1945 (UK). -

The Lillevik Dyke Complex, Narvik: Geochemistry and Tectonic Implications of a Probable Ophiolite Fragment in the Caledonides of the Ofoten Region, North Norway

The Lillevik dyke complex, Narvik: geochemistry and tectonic implications of a probable ophiolite fragment in the Caledonides of the Ofoten region, North Norway ROGNVALD BOYD Boyd, R.: The Lillevik dyke complex, Narvik: geochemistry and tectonic implications of a probable ophiolite fragment in the Caledonides of the Ofoten region, North Norway. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 63, pp. 39-54. Oslo 1983, ISSN 0029-196X. The Lillevik dyke complex occurs in an allochthonous unit and shows field relationships indicative of a transition from the mafic cumulate to the sheeted dyke zone in a segment of an ophiolite. Major and trace element chemistry confirm the MORB character of most of the diabases. Certain diabase, gabbro and trondhjemite dykes have REE patterns suggesting a later stage of ocean-island volcanism. The Lillevik complex and equivalent bodies along strike on the eastern limb of the Ofoten synform are a probable source for the mafic facies of the overlying Elvenes Conglomerate. Analogies with other areas suggest that the Lillevik complex was obducted during the Finnmarkian orogeny. R. Boyd, Norges geologiske undersøkelse, Postboks 3006, N-7001 Trondheim, Norway. The topic of this paper is a tectonically bounded gen Groups is marked by a conglomerate hori lens, consisting of gabbro cut by diabase and zon, the Elvenes Conglomerate, which consists gabbroic dykes and by leucocratic veins, which is mainly of matrix-supported cobbles of meta exposed on a shore section within the town of trondhjemite, quartzite and dolomitic marble in Narvik in North Norway. The section Iies in the a matrix of calcareous mica schist (Foslie 1941, upperrnost part of the Narvik Group of Gustav Gustavson 1966); this unit is currently being son (1966, 1972) (Fig. -

NARVIK – Norwegian Eldorado for Wreck-Divers Wrecks of Narvik

NARVIK – Norwegian Eldorado for wreck-divers Wrecks of Narvik Text by Erling Skjold (history and diving) and Frank Bang (diving) Underwater photography by Frank Bang Ship photography by Erling Skjolds, NSA collection Translation by Michael Symes Dieter von Roeder The port of Narvik in north Norway was established around the export of iron-ore from Sweden. This was due to the very good harbour and its ice-free con- ditions. At the outbreak of World War II, Narvik was a strategically important harbour, and during the first few days of the war a very intense battle was fought out here between German, Norwegian and British naval forces. During this fighting several ships were sunk, both warships and civil merchant ships. Narvik harbour was transformed into a great ship ceme- tery, with wrecks sticking up out of the water every- where. Several of the ships were later salvaged, but many wrecks still remained. With its high density of wrecks, Narvik is an eldorado for wreck divers. A diver explores the wreck of the German destroyer Hermann Künne in Trollvika 61 X-RAY MAG : 5 : 2005 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY EDUCATION PROFILES PORTFOLIO CLASSIFIED features Narvik Wrecks www.navalhistory.net Narvik harbour Maps outline battles in Narvik and around Norway during World War II Narvik harbour The importance of Narvik as a strate- Attack on April 9th the Eidsvold in just a few seconds. The that it was British gic harbour increased immediately at The German attack was a great surprise German ships could thereafter sail into forces that were the outbreak of World War II. -

AIBN Accident Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner, Oslo Airport, 18

Issued June 2020 REPORT SL 2020/14 REPORT ON THE AIR ACCIDENT AT OSLO AIRPORT GARDERMOEN, NORWAY ON 18 DECEMBER 2018 WITH BOEING 787-9 DREAMLINER, ET-AUP OPERATED BY ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES The Accident Investigation Board has compiled this report for the sole purpose of improving flight safety. The object of any investigation is to identify faults or discrepancies which may endanger flight safety, whether or not these are causal factors in the accident, and to make safety recommendations. It is not the Board's task to apportion blame or liability. Use of this report for any other purpose than for flight safety shall be avoided. Accident Investigation Board Norway • P.O. Box 213, N-2001 Lillestrøm, Norway • Phone: + 47 63 89 63 00 • Fax: + 47 63 89 63 01 www.aibn.no • [email protected] This report has been translated into English and published by the AIBN to facilitate access by international readers. As accurate as the translation might be, the original Norwegian text takes precedence as the report of reference. Photos: AIBN and Trond Isaksen/OSL The Accident Investigation Board Norway Page 2 INDEX ACCIDENT NOTIFICATION ............................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. FACTUAL INFORMATION .............................................................................................. 4 1.1 History of the flight ............................................................................................................. -

Interkommunal Kystsoneplan for Evenes, Narvik, Ballangen, Tysfjord Og Hamarøy

Mottaker: Evenes kommune Narvik kommune Ballangen kommune Tysfjord kommune Hamarøy kommune Fauske, 03.8.2019 Følgende organisasjoner har sluttet seg til uttalelsen: • Norsk Ornitologisk Forening avd. Nordland (NOF Nordland) • Norges Jeger- og Fiskerforbund Nordland (NJFF Nordland) • Naturvernforbundet i Nordland Vi beklager sent høringsinnspill, og håper våre merknader blir tatt med. Vi vil uansett følge opp dette i innspillsgruppene og i det videre planarbeid. Innspill til planprogram – interkommunal kystsoneplan for Evenes, Narvik, Ballangen, Tysfjord og Hamarøy Viser til høring av planprogram for interkommunal kystsoneplan for Evenes, Narvik, Ballangen, Tysfjord og Hamarøy. Kommunene har startet en interkommunal planprosess for å utarbeide en kystsoneplan for felles kystområder og fjordsystem. Bakgrunnen for planarbeidet er et ønske om en forutsigbar og bærekraftig forvaltning av sjøarealene. Arbeidet er organisert etter plan- og bygningsloven kapittel 9 interkommunalt plansamarbeid og det er opprettet et eget styre med en politisk valgt representant fra hver kommune. Dette styret har mottatt delegert myndighet fra kommunestyrene/ Bystyret til å varsle oppstart, fastsette planprogram og legge planforslag ut på høring. Endelig planprogram skal fastsettes i september 2019, og endelig vedtak av plan vil være september 2020. Planprosessen bygger på FNs bærekraftsmål og planprogrammet skisserer tre fokusområder for det videre arbeidet med planarbeidet. Dette er: • Akvakultur og fiskeri • Reise - og friluftsliv • Ferdsel __________________________________________________________________________________ forum for Forum for natur og friluftsliv i Nordland natur og Eiaveien 5, 8208 Fauske friluftsliv [email protected] / 90 80 61 46 Nordland www.fnf-nett.no/nordland Org. nr.: 983267998 FNF Nordlands merknader til planprogrammet FNF Nordland viser til de gode uttalelsene fra Narvik og Omegn JFF, Naturvernforbundet i Narvik og slutter oss til disse. -

Hovedrapport Ny Jernbane Fauske – Tromsø (Nord-Norgebanen) Oppdatert Kunnskapsgrunnlag

Hovedrapport Ny jernbane Fauske – Tromsø (Nord-Norgebanen) Oppdatert kunnskapsgrunnlag Dokument nr.: 21 007 105 Dato: 02.12.2019 Sammendrag Sammendrag Bakgrunn for oppdraget Jernbanedirektoratet har fått i oppdrag fra Samferdselsdepartementet å utarbeide et oppdatert kostnadsanslag og en samfunnsøkonomisk analyse for en ny jernbanestrekning Fauske – Tromsø (Nord-Norgebanen). Analysen skal baseres på den traseen som ble vurdert i Jernbaneverkets rapport «Jernbanens rolle i nord» i 2011. En trinnvis utbygging skal også vurderes. Vi skal ikke utarbeide en konseptvalgutrening, men følge KVU-metodikken så langt vi ser det som hensiktsmessig. Kostnadsanslaget skal være på et utredningsnivå innenfor +/- 40 prosent usikkerhet. Det er en forventning om økt produksjon av fisk og turisme som ligger til grunn for å gjøre nye vurderinger. Harstad er sentral i fiskerinæringen. Vi har derfor valgt å også se på en sidearm fra Bjerkvik til Harstad. I tillegg har vi sett en økning i kostnadene ved å bygge tunnel. Traseen fra 2011 har en tunnelandel på 58 prosent. Vi har derfor også sett på en trase som har 45 prosent tunnelandel slik at vi kan se hvordan færre tunneler virker inn på kostnadsbildet. En forenklet behovsanalyse, blant annet basert på de tre innspillskonferansene, viser at: • Det er behov for et pålitelig transportsystem med bedre kapasitet og regularitet for person- og godstransport • Det er behov for et transportsystem med smidige overganger mellom ulike transportformer • Det er behov for å transportere gods til det internasjonale markedet raskt og effektivt • Det er behov for å styrke trafikksikkerheten Vi etablerer ikke målstruktur for denne utredningen. Det vil først komme i en eventuell KVU-fase. -

A Vibrant City on the Edge of Nature 2019/2020 Welcome to Bodø & Salten

BODØ & SALTEN A vibrant city on the edge of nature 2019/2020 Welcome to Bodø & Salten. Only 90 minutes by plane from Oslo, between the archipelago and south, to the Realm of Knut Hamsun in the north. From Norway’s the peaks of Børvasstidene, the coastal town of Bodø is a natural second biggest glacier in Meløy, your journey will take you north communications hub and the perfect base from which to explore via unique overnight accommodations, innumerable hiking trails the region. The town also has gourmet restaurants, a water and mountain peaks, caves, fantastic fishing spots, museums park, cafés and shopping centres, as well as numerous festivals, and cultural events, and urban life in one of the country’s including the Nordland Music Festival, with concerts in a beautiful quickest growing cities, Bodø. In the Realm of Hamsun in the outdoor setting. Hamsun Centre, you can learn all about Nobel Prize winner Knut Hamsun`s life and works, and on Tranøy, you can enjoy open-air This is a region where you can get close to natural phenomena. art installations against the panoramic backdrop of the Lofoten There is considerable contrast – from the sea to tall mountains, mountain range. from the midnight sun to the northern lights, from white sandy beaches to naked rock. The area is a scenic eldorado with wild On the following pages, we will present Bodø and surroundings countryside and a range of famous national parks. Here, you can as a destination like no other, and we are more than happy immerse yourself in magnificent natural surroundings without to discuss any questions, such as possible guest events and having to stand in line. -

Project Description

Project Description Without Them I Am Lost: Storytelling as Survival Project Summary In 1944, the German army displaced 75,000 Northern Norwegians. Today, the remaining survivors who remember that time are dying before their stories can be told. We will collect and archive these stories of survival from Troms and Finnmark and Nordland Counties to create an intimate, feature-length documentary film. Logline Sharing memories is an act of survival. Without Them I Am Lost braids three layers of inquiry: oral histories of WWII in the northernmost part of Norway, the influence of landscape on the imagination, and the materiality of remembrance. Project Objectives We will create a feature length documentary to record and transmit Northern Norway’s oral histories of survival from the WWII era. Our objectives are (1) to give voice to underrepresented stories from Norway’s northernmost regions; (2) translate the stories for Norwegian, U.S., and other English-speaking audiences; and (3) foster intergenerational dialogue and exchange among and between Norway’s northern and southern regions, specifically those in Troms and Finnmark and Nordland Counties, in addition to Norwegian-American communities in the United States. Artistic Approach Without Them I Am Lost will juxtapose the sweeping landscapes of Northern Norway against images and artifacts that hold memories for our subjects. Alongside traditional interview framing techniques, we will film the interior locations of our subjects’ homes using macro shots of objects and gestures that will pull viewers into a new, intimate relationship with the material objects and people’s connections with them. The work of Dutch still-life vanitas painters and Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi serve as visual references in our approach for capturing objects and the human experience of them. -

Nabo Buss´N BUSSFORBINDELSE TIL NARVIK – FAUSKE / BODØ ARVIK N

254% NaBo buss´n BUSSFORBINDELSE TIL NARVIK – FAUSKE / BODØ ARVIK N FOTO: DESTINATION NARVIK ESTINATION : D OTO Velkommen til Narvik! F Narvik i Ofoten er omringet av vakker natur med fjell og fjorder som karakteriserer området rundt Narvik - Ofoten. Med nærhet og korte avstander til Lofoten, FOTO: DESTINATION NARVIK Vesterålen, Troms og Nord-Sverige er det enkelt å finne veien hit for en kort weekendtur eller en lengre opplevelsesferie. www.destinationnarvik.com Tjeldsund Bognes Evenes LH Ulsvåg Skarberget DGE E Bodø Hopen RCTIC Ballangen Råna / A Tømmerneset INNHAVET Narvik Helldalisen Langst LSEN Mørsvik O Skjomen Beisfjord INAR Romba botn E AG AGNUS Kobbelveid M : D Straumen OTO F VERRE : S JØRSETH OTO F B Velkommen til Bodø! Det tas forbehold om endringer i ruteterminen. Ruteopplysning: Se nettside på www.177.no Bodø - fylkeshovedstaden i Nordland, er Nord-Norges nest Ring 177 eller spør sjåføren. største by rammet inn av de URUHATT F vakreste naturgitte omgivelser. RNST fagtrykkide.no Noen av attraksjonene vi har i : E OTO Bodø er Saltstraumen, kjerringøy,, F Norsk luftfartsmuseum m.fl. www.visitnordland.no &RA.ARVIK $ $ &RA"OD $ $ .!26)+RUTEBILST AVG 07:00 16:10 "/$ AVG 07:00 16:15 3KJOMBRUA ³´ 07:20 16:30 ,DING ³´ 07:30 16:45 "ALLANGEN ³´ 07:45 17:00 3TRAUMSNES ³´ 07:50 17:05 &ORSkVEGKRYSS ³´ - - &AUSKERUTEBILST ³´ 08:10 17:25 3TRANVEGKRYSS ³´ 08:05 17:20c &AUSKEJBST ANK 08:15 17:30k 3KARBERGET ³´ 08:35 17:45 &AUSKEJBST AVG 08:55 18:10 "OGNES ³´ 09:05 18:10 3TRAUMENSENTR ³´ | | 5LVSVkG ³´ 09:25 18:35 -EGkRDEN ³´ 09:15 18:25 $RAGVEGKRYSS -

Vi Er Jo Et Militært Parti Blanding Av Militarisme, Antikommunisme, Rasistisk Nordisme Og Høyreradikal Anti-Parlamentarisme

Lars Borgersrud lars borgersrud et var en sentral krets av norske offiserer som startet D NS og partiets forløper, Nordiske Folkereisning. Målet var å knuse arbeiderbevegelsen og «politikerveldet» og reise en stat for «den nordiske rase». Sammen med «herskerrasene» i Nord-Europa skulle de gjenerobre gammelt nordisk land i Nord-Russland. De var noen av landets fremste offiserer og fikk med en gang oppslutning fra kretser i næringslivet og ytre høyre i politik- ken. Ideologien deres var en særegen norsk militærfascisme, en Vi er jo et blanding av militarisme, antikommunisme, rasistisk nordisme og høyreradikal anti-parlamentarisme. Framfor alt var de en statskuppbevegelse. NS-tillitsmenn og politiske kadre var verken uforberedt eller overrasket da føreren proklamerte sitt statskupp om ettermiddagen 9. april. Denne boken bringer fram i lyset en mengde ny kunnskap fra de militære arkivene og fra NS-arkivene. Her blir Quislings parti militært kupprosjekt fra 1932 for første gang dokumentert i detalj og inngående analysert. revidert utgave Lars Borgersrud (f. 1949) er cand. philol. ved Universitetet i Bergen 1975, dr. philos. i moderne historie ved Universitetet i Oslo 1995, ansatt ved Universitetet i Oslo Vi er jo et 2001–2004, statsstipendiat til 2016. militært parti ISBN 978-82-304-0226-9 www.scandinavianacademicpress.no Den norske militærfascismens historie I Lars Borgersrud – Vi er jo et militært parti Den norske militærfascismens historie 1930–1945 bind 1 – Vi er jo et militært parti! © Scandinavian Academic Press / Spartacus forlag AS 2010. 2. reviderte utgave, 2018. Omslag: Lukas Lehner / Punktum forlagstjenester Omslagsbilde: Vidkun Quisling sammen med NS-partifeller. Bildet er trolig fra mai 1934, antakelig i forbindelse med stiftelsen av Nasjonal Ungdomsfyl- king.