Burial Crypts and Vaults in Britain and Ireland: a Biographical Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

(Virtual) Meeting Agenda Tuesday, February 9, 2021 @ 6:00 PM

Page 1 of 74 Graham City Council Regular (Virtual) Meeting Agenda Tuesday, February 9, 2021 @ 6:00 P.M. Meeting called to order by the Mayor Invocation & Pledge of Allegiance 1. Consent Agenda: a. Approve Minutes – January 12, 2021 Regular Session (Virtual) b. Approve Minutes – January 27, 2021 Special Session c. Approve Tax Refund d. Approve Tax Collector’s Mid-Year Report e. Authorize the City Manager to enter into a Lease Agreement with Carolina Property Holdings for the joint use of the alleyway located at 200 North Main Street f. Approve Ordinance Amendment to CHAPTER 20, TRAFFIC AND VEHICLES, ARTICLE V, STANDING, STOPPING AND PARKING of the Code of Ordinances to require the location of the Downtown Residential Parking Permit be placed on rear windshield and establish a $20 annual permit fee, and update the Rates & Fee Schedule accordingly g. Approve Initial Project Budget for the WWTP Upgrades and Expansion Project 2. Old Business: a. Public Hearing: AN2007 Middlefield Towns. Annexation Ordinance for Voluntary Non- Contiguous Annexation for 5.5 (+/-) acre lot located at 2048 South Main Street (GPIN 8882397172) b. Amendment to CHAPTER 20, ARTICLE V, PARADES, DEMONSTRATIONS AND STREET EVENTS of the Code of Ordinances 3. Recommendations from Planning Board: a. Public Hearing: RZ2010 Riverbend Business. Request by G. Travers Webb III to rezone a portion of the property located on East Harden Street from R-MF (Multi-Family Residential) to B-2 (General Business) (GPIN 8884721949) b. Public Hearing: CR2006 Truby Apartments. Request by Second Partners, LLC for Conditional Rezoning for multi-family apartments from Light Industrial for property located on (GPIN 8894453334) c. -

Historic Cemeteries Preservation Guide / Gregg King

Historic Cemeteries Michigan Preservation Guide Gregg G. King with Susan Kosky, Kathleen Glynn & Gladys Saborio Supported by Michigan Historic Cemetery Preservation Manual GREGG G. KING with SUSAN KOSKY KATHLEEN GLYNN GLADYS SABORIO SUPPORTED BY: Michigan State Historic Preservation Office and The Charter Township of Canton Historic District Commission and Department of Leisure Services Published with the assistance of Charter Township of Canton Copyright by Charter Township of Canton 2004 All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, excluding forms, without written permission from the above named publisher. Cover designed by RaeChell Garrett and Gregg G. King Printed in the United States of America by McNaughton and Gunn Inc. ISBN 0-9755474-0-2 Publishers Cataloging -in- Publication King, Gregg Michigan historic cemeteries preservation guide / Gregg King. p.cm. Includes biographical references. ISBN 0-9755474-0-2 I. Cemeteries—Michigan—Conservation and restoration —Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Historic preservation— Michigan—Handbooks, manuals, etc. 3. Michigan— Antiquities—Collections and preservation— Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title F567.K56 2004 363.6’9 QBI04-200244 The activity that is the subject of this project has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Michigan Department of History, Arts and Libraries. However, the contents and opinions herein do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Department of History, Arts and Libraries, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products herein constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Michigan Department of History, Arts and Libraries. -

“My Verses, Like Old Vines, Will Come to Their Turn Sometimes...” M. Tsvetaeva Sarigian 00 Teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·2 Sarigian 00 Teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·3

sarigian 00 teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·1 “My verses, like old vines, will come to their turn sometimes...” M. Tsvetaeva sarigian 00 teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·2 sarigian 00 teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·3 NECROPOLIS of GONUR sarigian 00 teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·4 NECROPOLISNECROPOLIS Photography by Viacheslav Sarkisian, Aleksandr Djus, Anna Rosa Cengia, Nadejda Dubova. Some photos were kindly given by the President of Ligabue Study and Research Centre Dr. Giancarlo Ligabue All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or repub- lished, wholly or in part, or in summary, paraphrase or adaptation, by mechanical or electronic means, by photocopying or recording, or by any other method, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Law 2121/1993 and the regulations of International Law applicable in Greece. © 2007 Victor Sarianidi © 2007 ∫APON EDITIONS 23-27 Makriyanni Str., Athens 117 42, Greece Tel./Fax: (210) 9214 089, 9235 098 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-960-7037-85-5 sarigian 00 teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·5 VICTOR SARIANIDI English Translation by INNA SARIANIDI ofof GONURGONUR sarigian 00 teliko 5/4/2007 9:36 PM ™ÂÏ›‰·6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . 7 BACKGROUND . 9 CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 3 FUNERAL CONSTRUCTIONS AT THE GONUR INDO-IRANIANS AND A DOMESTIC HORSE . 126 NECROPOLIS . 20 3.1. The Burial of a Horse . 126 1.1. Funeral Rites in Southern Turkmenistan in the 3.2. Horse in Margiana and BMAC . 130 Fourth-Third Millennia B.C. -

Terms Used to Describe Cemeteries and Grave

TERMS USED TO DESCRIBE CEMETERIES AND GRAVE MARKERS altar tomb - A solid, rectangular, raised tomb or gravernarker resembling ceremonial altars of classical antiquity and Judeo-Christian ritual. bevel marker -A rectangular gravemarker, set low to the ground, having straight sides and uppermost, inscribed surface raked at a low angle. bolster - a form of gravestone where a cylinder (usually at least 18 inches in diameter and 36 or more inches long) rests on its side on a footing. Bolsters were most common in the early twentieth century burial – grave; the body within the grave; the act of burying a body. burial, primary - a burial where the body is placed in its grave shortly after death, with no prior or temporary burial. Primary burial is the most common form of burial in most modem cemetery traditions burial, secondary - a burial where the body has spent considerable time (often several years) in a temporary resting place before removal to its final resting place. Secondary burials have been fairly common in various death traditions around the worfd and persist mostly in traditions that have strong non-Western folk elements burial, urn - the burial of an urn with cremated remains in it. burial axis- the line that follows along the length of the body in a burial; the "length" of the grave burial ground - Also "burying ground;" same as "graveyard" burial site - A place for disposal of burial remains, including various forms of encasement and platform burials that are not excavated in the ground or enclosed by mounded earth. cairn - a pile of rocks. Cairns can be erected over graves as markers, as bases to support crosses or other upright markers, or as protective devices from scavenging animals. -

Management of Dead Bodies in Disaster Situations

Management of Dead Bodies in Disaster Situations Disaster Manuals and Guidelines Series, Nº 5 World Health Organization Area on Emergency Preparedness Department for and Disaster Relief Health Action in Crisis Washington, D.C., 2004 Also published in Spanish (2004 with the title: Manejo de cadáveres en situaciones de desastre (ISBN 92 75 32529 4) PAHO Cataloguing in Publication Pan American Health Organization Management of Dead Bodies in Disaster Situations Washington, D.C: PAHO, © 2004. 190p, -- (Disaster Manuals and Guidelines on Disasters Series, Nº 5) ISBN 92 75 12529 5 I. Title II. Series 1. DEAD BODY 2. NATURAL DISASTER 3. DISASTER EMERGENCIES 4. DISASTER EPIDEMIOLOGY LC HC553 © Pan American Health Organization, 2004 A publication of the Area on Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in collaboration with the Department Health Action in Crises of the World Health Organization (WHO). The views expressed, the recommendations made, and the terms employed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the current criteria or policies of PAHO/WHO or of its Member States. The Pan American Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate, in part or in full, this publication. Applications and inquiries should be addressed to the Area on Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief, Pan American Health Organization, 525 Twenty-third Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20037, USA; fax: (202) 775-4578; e-mail: [email protected]. This publication has been made possible through the financial support of the Division of Humanitarian Assistance, Peace and Security of the Canadian International Development Agency (IHA/CIDA), the Office for Foreign Disaster Assistance of the United States Agency for International Development (OFDA/USAID), the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), and The European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid department (ECHO). -

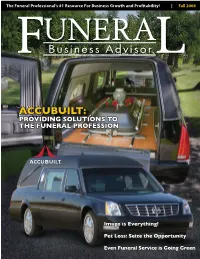

FBA Fall 2006 Issue

The Funeral Professional’s #1 Resource For Business Growth and Profitability! | Fall 2006 TM AACCCCUBUILT:UBUILT: PPROVIDINGROVIDING SSOLUTIONSOLUTIONS TTOO TTHEHE FFUNERALUNERAL PPROFESSIONROFESSION IImagemage iiss EEverything!verything! Peett LLoss:oss: SSeizeeize tthehe OpportunityOpportunity EEvenven FFuneraluneral ServiceService isis GoingGoing GreenGreen "REMEMBER...NOT ALL BURIAL VAULTS ARE CREATED EQUAL!" MANUFACTURER OF THE NEXT GENERATION BURIAL VAULT THE EONIAN BURIAL VAULT PASSED A CENTER LOAD TEST OF 28,100 LBS. WITHOUT BREAKING DURING A RECENT ENGINEERING TEST. THIS SHATTERS CONCRETE'S 5,000 LBS. MINIMUM Eonian Infant Casket/Vault (Double Premium Protection) Eonian Cremation Urn Vault (Double Premium Protection) White granite casket vault combination lined in a flowing soft fabric. Includes a Choose from Blue, Dark Gray, White, lamb with a pink or blue bow and a lock Eonian (Triple Premium Protection) Sandstone or Rose of Sharon granites Outside: 17 1/4 x 17 1/4 with keepsake keychain. Choose from Blue, Dark Gray, White, Inside: 12 1/4 (W) x 13 3/4 (H) Small 24"(L) x12"(W) x9"(H) Sandstone or Rose of Sharon granites Large 32"(L) x16"(W) x12"(H) Eonian (Triple Premium Protection) Eonian (Triple Premium Protection) Copper Shimmer with Carapace Copper Patina without Carapace TOLL FREE 866-418-4939 The Funeral Professional’s #1 Resource For Business Growth and Profitability! | Fall 2006 TM ACCUBUILT:ACCUBUILT: PROVIDING SOLUTIONS TO THE FUNERAL INDUSTRY The Funeral Professionalʼs #1 Resource for Business Growth and Profi tability! Image is Everything! PetPet LoLoss:ss: Seize the Opportunity FEATURE Even Funeral Service is Going Green Contents Fall 2006 20 ACCUBUILT: Providing Solutions to the Funeral Profession SOLUTIONS ON LEADERSHIP 14 Changing Times | by Ronald H. -

Notice of Intent to Adopt a Mitigated Negative Declaration

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT/RESOURCE AGENCY ENVIRONMENTAL COORDINATION SERVICES County of Placer NOTICE OF INTENT TO ADOPT A MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION The project listed below was reviewed for environmental impact by the Placer County Environmental Review Committee and was determined to have no significant effect upon the environment. A proposed Mitigated Negative Declaration has been prepared for this project and has been filed with the County Clerk's office. PROJECT: Gladding Eternal Preserve (PLN17-00420) PROJECT DESCRIPTION: The project proposes construction of a green burial (natural burial) cemetery on 160.3 acres of land. Approximately 61.3 acres of the site would be used for interments and would accommodate approximately 10,000 to 15,000 graves and approximately 4,000 plots for cremains upon completion. A portion of one or more of the interment areas may be used for pet burials. The balance of the site would be left in its natural condition. Publicly-accessible trails would provide access and connect the interment areas. PROJECT LOCATION: Southeast Corner of Gladding Road and Fleming Road, Rural Lincoln, Placer County APPLICANT: Phillips Land Law, Inc., Kris Steward The comment period for this document closes on November 27, 2018. A copy of the Mitigated Negative Declaration is available for public review at the County’s web site http://www.placer.ca.gov/Departments/CommunityDevelopment/EnvCoordSvcs/NegDec.aspx Community Development Resource Agency public counter, and at the Lincoln Public Library. Property owners within 300 feet of the subject site shall be notified by mail of the upcoming hearing before the Planning Commission. Additional information may be obtained by contacting the Environmental Coordination Services, at (530)745-3132, between the hours of 8:00 am and 5:00 pm. -

The Cask of Amontillado Study Guide

The Cask of Amontillado Study Guide © 2018 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary Told in the first person by an Italian aristocrat, “The Cask of Amontillado” engages the reader by making him or her a confidant to Montresor’s macabre tale of revenge. The victim is Fortunato, who, the narrator claims, gave him a thousand injuries that he endured patiently, but when Fortunato dared insult him, he vowed revenge. It must be a perfect revenge, one in which Fortunato will know fully what is happening to him and in which Montresor will be forever undetected. To accomplish it, Montresor waits until carnival season, a time of “supreme madness,” when Fortunato, already half-drunk and costumed as a jester, is particularly vulnerable. Montresor then informs him that he has purchased a pipe of Amontillado wine but is not sure he has gotten the genuine article. He should, he says, have consulted Fortunato, who prides himself on being an expert on wine, adding that because Fortunato is engaged, he will go instead to Luchesi. Knowing his victim’s vanity, Montresor baits him by saying that some fools argue that Luchesi’s taste is as fine as Fortunato’s. The latter is hooked, and Montresor conducts him to his empty palazzo and leads him down into the family catacombs, all the while plying him with drink. -

The Old Cemetery for Foreigners in Rome with a New Inventory of Its Burials

SVENSKA INSTITUTEN I ATHEN OCH ROM INSTITUTUM ATHENIENSE ATQUE INSTITUTUM ROMANUM REGNI SUECIAE Opuscula Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome 13 2020 STOCKHOLM Licensed to <[email protected]> EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Prof. Gunnel Ekroth, Uppsala, Chairman Dr Lena Sjögren, Stockholm, Vice-chairman Mrs Kristina Björksten Jersenius, Stockholm, Treasurer Dr Susanne Berndt, Stockholm, Secretary Prof. Christer Henriksén, Uppsala Prof. Anne-Marie Leander Touati, Lund Prof. Peter M. Fischer, Göteborg Dr David Westberg, Uppsala Dr Sabrina Norlander-Eliasson, Stockholm Dr Lewis Webb, Göteborg Dr Ulf R. Hansson, Rome Dr Jenny Wallensten, Athens EDITOR Dr Julia Habetzeder Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm [email protected] SECRETARY’S ADDRESS Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm [email protected] DISTRIBUTOR eddy.se ab Box 1310 SE-621 24 Visby For general information, see http://ecsi.se For subscriptions, prices and delivery, see http://ecsi.bokorder.se Published with the aid of a grant from The Swedish Research Council (2017-01912) The English text was revised by Rebecca Montague, Hindon, Salisbury, UK Opuscula is a peer reviewed journal. Contributions to Opuscula should be sent to the Secretary of the Editorial Committee before 1 November every year. Contributors are requested to include an abstract summarizing the main points and principal conclusions of their article. For style of references to be adopted, see http://ecsi.se. Books for review should be sent to the Secretary of the Editorial Committee. ISSN 2000-0898 ISBN 978-91-977799-2-0 © Svenska Institutet i Athen and Svenska Institutet i Rom Printed by TMG Sthlm, Sweden 2020 Cover illustrations from Aïopoulou et al. -

Phase II and Phase III Archeological Database and Inventory

Phase II and Phase III Archeological Database and Inventory Site Number: 18PR224 Site Name: Buck House, Wardrop-Buck House Prehistoric Other name(s) Darnall's Chance (PG:79-28) Historic Brief late 17th-early 19th century plantation complex and burial vault Unknown Description: Site Location and Environmental Data: Maryland Archeological Research Unit No. 8 SCS soil & sediment code GaB Latitude 38.8258 Longitude -76.7521 Physiographic province Western Shore Coastal Terrestrial site Underwater site Elevation 0 m Site slope 0-5% Ethnobotany profile available Maritime site Nearest Surface Water Site setting Topography Ownership Name (if any) Schoolhouse Pond -Site Setting restricted Floodplain High terrace Private Saltwater Freshwater -Lat/Long accurate to within 1 sq. mile, user may Hilltop/bluff Rockshelter/ Federal Ocean Stream/river need to make slight adjustments in mapping to cave Interior flat State of MD account for sites near state/county lines or streams Estuary/tidal river Swamp Hillslope Upland flat Regional/ Unknown county/city Tidewater/marsh Lake or pond Ridgetop Other Unknown Spring Terrace Low terrace Minimum distance to water is 0 m Temporal & Ethnic Contextual Data: Contact period site ca. 1820 - 1860 Y Ethnic Associations (historic only) Paleoindian site Woodland site ca. 1630 - 1675 ca. 1860 - 1900 Y Native American Asian American Archaic site MD Adena ca. 1675 - 1720 Y ca. 1900 - 1930 Y African American Unknown Early archaic Early woodland ca. 1720 - 1780 Y Post 1930 Y Anglo-American Y Other MIddle archaic Mid. woodland ca. 1780 - 1820 Y Hispanic Late archaic Late woodland Unknown historic context Unknown prehistoric context Unknown context Y=Confirmed, P=Possible Site Function Contextual Data: Historic Furnace/forge Military Post-in-ground Urban/Rural? Rural Other Battlefield Frame-built Domestic Prehistoric Transportation Fortification Masonry Homestead Multi-component Misc. -

“To Lie in Yonder Tomb”: the Tomb and Burial of Joseph Smith

Joseph D. Johnstun: The Tomb and Burial of Joseph Smith 163 “To Lie in Yonder Tomb”: The Tomb and Burial of Joseph Smith Joseph D. Johnstun I have said, Father, I desire to die here among the Saints. But if this is not Thy will, and I go hence and die, wilt thou find some kind friend to bring my body back, and gather my friends who have fallen in foreign lands, and bring them up hither, that we may all lie together. I will tell you what I want. If tomorrow I shall be called to lie in yonder tomb, in the morning of the resurrection let me strike hands with my father, and cry, “My father,” and he will say, “My son, my son,” as soon as the rock rends and before we come out of our graves.1 (Joseph Smith) “The Tomb of Joseph, a Descendant of Jacob” One of Joseph Smith’s greatest desires was a proper resting place for his body once he died. He said on the occasion of the funeral of Lorenzo Barnes, “It has always been considered a great calamity not to obtain an honorable burial: and one of the greatest curses the ancient prophets could put on any man, was that he should go without a burial.”2 The nineteenth century was a time of high mortality rates, and the loss of loved ones and friends for Joseph Smith dominated much of his thought during the last few years of his life. His close associate, Benjamin F. Johnson, noted five songs that were among the Prophet’s favorites.3 All five had the theme of mortality.