Rationales Shaping International Linkages in Higher Education: a Qualitative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Higher Education Database Whed Iau Unesco

WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Página 1 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Education Worldwide // Published by UNESCO "UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA" "NATIONAL UNION OF CONTINUOUS ORGANIZED HIGHER EDUCATION" IAU International Alliance of Universities // International Handbook of Universities © UNESCO UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA 2017 www.unesco.vg No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted without written permission. While every care has been taken in compiling the information contained in this publication, neither the publishers nor the editor can accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions therein. Edited by the UNESCO Information Centre on Higher Education, International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] Director: Prof. Daniel Odin (Ph.D.) Manager, Reference Publications: Jeremié Anotoine 90 Main Street, P.O. Box 3099 Road Town, Tortola // British Virgin Islands Published 2017 by UNESCO CENTRE and Companies and representatives throughout the world. Contains the names of all Universities and University level institutions, as provided to IAU (International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] ) by National authorities and competent bodies from 196 countries around the world. The list contains over 18.000 University level institutions from 196 countries and territories. Página 2 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO World Higher Education Database Division [email protected] -

Donations Collected at the BBVA Stadium on Game Days to Pay for Treatments And/Or Medications for Minors Through Associations, Institutions Or Individuals

2020 ANNUAL REPORT ON SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 1 01. INDEX 01. 02. 03. 04. 05. INDEX MESSAGE FROM INSTITUTIONAL RAYADOS’ VALUES RAYADOS’ SOCIAL THE BOARD PRINCIPLES TASK PRESIDENT Page 01 Page 03 Page 05 Page 07 Page 08 06. 07. 08. 09. 10. CORE STRATEGIES COVID-19 SOCIAL PARTNERSHIPS YOUTH ACADEMY Core 1.- Our Children AID PROGRAM AWARENESS AND PROJECT Core 2.- Rayados’ Values COLLABORATIONS Core 3.- Blue Planet Core 4.- Alliances Page 09 Page 45 Page 53 Page 55 Page 59 11. 12. 13. VOICES OF OUR THE COURAGEOUS 2021 OBJECTIVES YOUTH ELEVEN Page 65 Page 67 Page 70 2 3 Dear Friends: MESSAGE FROM During 2020 our Institution, as well as our country and the entire THE BOARD world, confronted the coronavirus pandemic, a situation that has challenged society as a whole in an unprecedented manner. PRESIDENT This health emergency has caused numerous and unfortunate con- sequences. Without a doubt, the most important one has been the loss of many human lives, as well as the effect it has had on econo- mies around the world and, as a consequence, the effect it has also had on people’s economic situations. The impact of COVID-19 has required extraordinary measures to be taken by everyone: country governments have taken measures to avoid the spread of the virus, private and government sectors have strengthened medical resources and the capacity to attend affec- ted people, the temporary suspension of certain economic activi- ties that affected almost all industrial productive chains and the suspension of all large-scale events. Throughout the year, the pandemic required the attention and par- ticipation of the entire community. -

List of English and Native Language Names

LIST OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE LANGUAGE NAMES ALBANIA ALGERIA (continued) Name in English Native language name Name in English Native language name University of Arts Universiteti i Arteve Abdelhamid Mehri University Université Abdelhamid Mehri University of New York at Universiteti i New York-ut në of Constantine 2 Constantine 2 Tirana Tiranë Abdellah Arbaoui National Ecole nationale supérieure Aldent University Universiteti Aldent School of Hydraulic d’Hydraulique Abdellah Arbaoui Aleksandër Moisiu University Universiteti Aleksandër Moisiu i Engineering of Durres Durrësit Abderahmane Mira University Université Abderrahmane Mira de Aleksandër Xhuvani University Universiteti i Elbasanit of Béjaïa Béjaïa of Elbasan Aleksandër Xhuvani Abou Elkacem Sa^adallah Université Abou Elkacem ^ ’ Agricultural University of Universiteti Bujqësor i Tiranës University of Algiers 2 Saadallah d Alger 2 Tirana Advanced School of Commerce Ecole supérieure de Commerce Epoka University Universiteti Epoka Ahmed Ben Bella University of Université Ahmed Ben Bella ’ European University in Tirana Universiteti Europian i Tiranës Oran 1 d Oran 1 “Luigj Gurakuqi” University of Universiteti i Shkodrës ‘Luigj Ahmed Ben Yahia El Centre Universitaire Ahmed Ben Shkodra Gurakuqi’ Wancharissi University Centre Yahia El Wancharissi de of Tissemsilt Tissemsilt Tirana University of Sport Universiteti i Sporteve të Tiranës Ahmed Draya University of Université Ahmed Draïa d’Adrar University of Tirana Universiteti i Tiranës Adrar University of Vlora ‘Ismail Universiteti i Vlorës ‘Ismail -

Measuring the Construction of the Human Cognition Schema of Psychology Students

1 International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 1-21, February 2021 https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.20.2.1 Chronometric Constructive Cognitive Learning Evaluation Model: Measuring the Construction of the Human Cognition Schema of Psychology Students Guadalupe Elizabeth Morales-Martinez and Janneth Trejo-Quintana Cognitive Science Laboratory, IISUE, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4662-229X https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7701-6938 David Jose Charles-Cavazos TecMilenio University, Mexico City, Mexico https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3445-9026 Yanko Norberto Mezquita-Hoyos Autonomous University of Yucatán, Yucatan, Mexico https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6305-7440 Miriam Sanchez-Monroy Tecnologico Nacional de Mexico-Instituto Tecnologico de Merida, Yucatan, Mexico https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5263-1216 Abstract. This study measured the structural and organizational changes in the knowledge schema of human cognition in response to the learning achieved by 48 students enrolled in the second year of a psychology degree. Two studies were carried out based on the Chronometric Constructive Cognitive Learning Evaluation Model. This article deals only with the first one, which consisted of a conceptual definition task designed in line with the Natural Semantic Network technique. Participants defined ten target concepts with verbs, nouns, or adjectives (definers), and then weighed the grade of the semantic relationship between the definers and the target concepts. The data indicate that the initial knowledge structures had been modified towards the end of the course. The participants’ human cognition schema presented changes in terms of content, organization, and structure. -

Summary Report Introduction Environmental Sustainability and Planetary Boundaries, New Sources of Data, and Behavioural Insights for Policy

Summary Report Introduction environmental sustainability and planetary boundaries, new sources of data, and behavioural insights for policy. Each of these issues was addressed Over 1400 participants from 60 countries attended from the perspective of how better evidence and th the 5 OECD World Forum on Statistics, measurement can lead to concrete change in policy th Knowledge and Policy in Guadalajara on the 13-15 and behaviour to improve people’s lives. In this October 2015, co-organised by OECD and INEGI, regard, a major underlying theme of the whole with the support of the Government of Jalisco. Over conference was the impact of the newly-launched the three days, panellists from all di erent sectors Sustainable Development Goal agenda (launched at of society – including government, civil society, the UN General Assembly the month before), which national statistics o ces, international organisations, itself has integrated well-being and sustainability press, and the private sector – presented examples concerns into a much broader and inclusive set of initiatives related to the Forum theme of of goals and targets than its predecessor, the “Transforming Policy, Changing Lives” to improve Millennium Development Goal agenda. In addition, well-being and sustainability. Sessions were held the Forum saw the public launches of several in a variety of formats to enable di erent kinds important projects: the 2015 edition of agship of interaction between speakers and with the OECD publication, “How’s Life?”, the joint OECD-INEGI audience, from Roundtables and Keynote speeches project on “Well-being in Mexican States” including in the Plenary Room, to issue-based Parallel Sessions the new INEGI System of Well-being Indicators in and Lunchtime Panels, and smaller workshops in Mexican States platform, and the OECD-led initiative the Morning Seminars. -

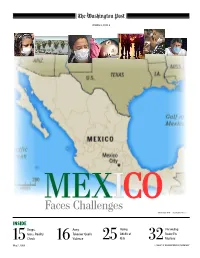

Faces Challengesico MAP by GENE THORP — the WASHINGTON POST

[ABCDE] VOLUME 8, Issue 9 MEXFaces ChallengesICO MAP BY GENE THORP — THE WASHINGTON POST INSIDE Drugs, Army Young Unraveling Guns, Reality Takeover Quells Adults at Swine Flu 15 Check 16 Violence 25 Risk 32 Mystery May 5, 2009 © 2009 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 8, Issue 9 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word About Mexico Faces Challenges Lessons: Mexico, a country with a rich Three times the size of Texas, Mexico is a country of cultural heritage and history, remains contrasts. From towering mountains to coastal lowlands, closely tied to the U.S. Lessons in tropics to deserts. A country of World Heritage sites economics, global health provisions and preserving a rich history and culture, and leaders in Mexico international policy are abundant as Mexico confronts the epidemics of drug City moving it into the 21st century. Ranked by the World trafficking, violence and the A/H1N1 virus. Bank as the twelfth largest economy in the world, it is For journalism teachers, the coverage of experiencing deep recession. these issues by The Post provides lessons in depth reporting and breaking news Mexico is a country of large cities of millions and dusty coverage. villages. It is a country of cathedrals, wayside shrines and devout respect for life facing drug cartels and violence. It Level: Mid to High is the latter that was the original focus of the May guide. Subjects: U.S. History, Journalism Following the meeting of presidents Obama and Calderón Related Activity: Economics, World in Mexico, Post photographers, writers and Foreign Service History, Health correspondents were covering the violence that has resulted from the flow of U.S.-made firearms south and drugs north of the shared border in a series called Mexico at War: On the Front Lines. -

Annual Integrated REPORT 2020 2 | AXTEL INFORME ANUAL INTEGRADO 2020

2 | AXTEL INFORME ANUAL INTEGRADO 2020 Annual Integrated REPORT 2020 2 | AXTEL INFORME ANUAL INTEGRADO 2020 Content Message from the CEO 4 Facing 2020 6 Company profile 7 Our business 9 Innovation 17 Data security 21 Customer experience 25 Corporate governance 29 Financial outlook 45 2 | AXTEL INFORME ANUAL INTEGRADO 2020 Sustainability 52 Employee wellbeing 60 Environmental concern 72 Financial statements 83 Report parameters 161 GRI, SASB and TCFD content index 162 Verification letter 171 Contact information 172 4 | AXTEL ANNUAL INTEGRATED REPORT 2020 Message from the CEO In 2020, we focused our actions at Axtel on over the guidance for the year and the results of three priorities: promoting the safety and well- 2019, which is a reflection of our resilient portfolio being of our employees, providing support to our of services, as well as the efficiencies generated customers for their crucial requirements, and by our digitalization initiatives. ensuring the continuity of our operations and of the organizations we have the privilege to serve. In line with our strategy of divesting non-strategic assets, in 2020 we carried out two relevant Through our strategic imperative "Axtel Digital", transactions. In January, we finalized a strategic we accelerated the digitalization and remote agreement for 175 million dollars with Equinix access to significant business processes, in 2019. Later, in July, we transferred nine strengthened our platform of collaborative tools concession titles covering the use, leveraging and and adopted remote work practices. In record exploitation of the 3.5 GHz frequency band for time we adopted a remote operation model under the provision of fixed wireless access services to which approximately 85% of our employees Telcel, recording a net profit of Ps. -

Flipped Learning

Edu Trends OCT 2014 Report Flipped Learning Table of Contents › Introduction: Flipped Learning 4 › Relevance for the Tecnológico de Monterrey 10 › Flipped Learning at Tecnológico de Monterrey 11 › What are other institutions doing? 14 › Where is this trend heading? 18 › A critical point of view 20 › Recommended Actions 23 › Credits and Acknowledgments 25 › References 26 Aa ~~ Flipped Learning A teaching approach where direct instruction is performed outside the classroom and face-time is used for significant and personalized learning activities. Introduction: Flipped Learning In most university classrooms, a typical scenario has to take advantage of class time for maximizing one-on- the teacher at the front “lecturing” and writing on the one interactions between teachers and students. board. The teacher is the central figure in the learning model – the sage on the stage –, while students take This model’s basic premise is that Direct Instruction is notes and are assigned homework at the end of effective when done individually, but given universities’ the lesson. The teacher knows or notices that many resources, this would require a much larger faculty students did not completely understand the day’s team which most institutions would be unable to pay lesson, but lacks sufficient time for meeting with each for (Bergmann & Sams, 2014, p. 29). This does not mean one individually to address their questions. During the that current instruction is necessarily poor: it can be an next lesson, the teacher will only gather and briefly effective way for acquiring new knowledge; the pace is review the homework, answer a few questions, but what is inconvenient. -

M-December2019-Web.Pdf

20 17 Table of Content M!Vol. 13, No. 3 The Gastronomic Scene .................................................... 5 Effervescent, Probiotic, M Tomatl Experiences .........................................................6 Fermented Tea... El Observador ..................................................................8 Create your own posadas .................................................10 Publisher A Merry Christmas Off the Streets .....................................12 Guy Ismond Wheeling for Awareness ................................................. 14 Becoming an Empowered Patient ......................................19 Contributors The Booster Club ........................................................... 20 It's Alive. Ana Fernandez Best Beats .................................................................... 22 Olivia Guzón Deborah Brannan M! is for Movies ............................................................ 23 Simon Lynds Best Bets ...................................................................... 24 TE Wilson Business Directory ..........................................................27 Photography M! Magazine Staff Design While you are here… Jorge Tirado Amarisa Kombucha 669 154 1605 You might notice a city wide campaign called ‘Yo Sí Res- Ad Sales peto Tus Espacios.' A campaign designed to raise awareness Available NOW at: of the challenges facing those in our city with mobility issues. Plaza Zaragoza - Sat/Sab - 8am-12pm [email protected] Over the past few years Mazatlán has made huge La Catrina Rest- Wed/Mier -

Connected to a New Era

Connected to a new era 2015 Annual Report 2 BBVA Bancomer Table of Contents About this Report 04 Group Profile 05 Corporate Philosophy 05 Mission and Vision 05 Corporate Principles 05 Corporate Governance 06 Corporate Governance System 06 Corporate Structure 06 Management Committee 06 Board of Directors 07 Compliance 07 Business Model 11 Materiality and Dialogue with Stakeholders 12 Responsible Business Plan 15 Social, Environmental and Reputational Risk 19 Leadership 22 Presence 23 Relevance of BBVA Bancomer in Mexico’s Economy 24 Report from the Chairman of the Board of Directors 25 Report from the Deputy Chairman of the Board of Directors and CEO 29 BBVA Bancomer by Business Units 33 Business Units 33 CRR Advertising Campaigns and Communication 39 Economic Impact 41 Analysis and Discussion of Business Development 41 Economic Value Added (EVA) by Stakeholder 44 Audited Financial Statements 45 Social Impact 45 Customers 45 Staff 47 Suppliers 54 Society 55 Environmental Impact 59 Appendixes 63 GRI Content Index 64 Independent Assurance Report 75 2015 Progress and 2016 Objectives 78 2015 Awards and Recognitions 96 Glossary 97 2015 Annual Report 3 BBVA Bancomer consolidates the leading position in the Mexican market 1,818 10,772 Branches ATMs 1,850,465 mdp 34,485 mdp Assets Net Income 1,672,191 m d p 857,322 m d p Liabilities Bank Deposits (demand + time) 882,663 mdp Performing Loans Also, BBVA Bancomer maintains its commitment to society, through the allocation of 1% of the net income for social projects. In 2015, more than MXN$409,000 billion were allocated. 4 BBVA Bancomer G4-3, G4-13, G4-17, G4-22, G4-23, G4-28, G4-29, G4-30, G4-32, G4-33 About this Report For easy location The 2015 BBVA Bancomer Annual Report shows the results of those activities carried out by purposes, relevant Grupo Financiero BBVA Bancomer S.A. -

Mexico's Clusters In

Mexico’s competitiveness clusters in industrial innovation BUSINESS UIN INTELLIGENCE UNIT © December 2017, ProMéxico www.promexico.mx Prepared by: BUSINESS UIN INTELLIGENCE UNIT Marco Erick Espinosa Vincens, Head of the Unit Claudia Esteves Cano, Executive Director of Strategy Jair Eridan Cabrera Padilla, Strategic and Prospective Projects Consultant (Project manager) Luisa Regina Morales Suárez, Editorial Design The information presented in this document was integrated with data from public sources and throu- gh the application of surveys to various companies. Therefore, ProMéxico is not responsible for any inaccuracies in the content. Pictures downloaded from: unsplash.com / pixabay.com / pexels.com Iconss downloaded from: flaticon.com I. Introduction p.4 II. Cluster identification methodology p.5 III. Cluster listing, classification and distribution p.7 INDEX IV. Competitiveness clusters mapping Map 1: Research, development, and technology Map 2: Digital factories Map 3: Automation integration, movement, and control Map 4: Energy (industrial efficiency and storage) Map 5: Industrial supply p.10 V. General findings about Mexico’s competitiveness clusters p.16 VI. Thematic Networks p.21 VII. Final remarks p.22 VIII. Fact Sheets p.23 IX. Bibliography p.65 I. INTRODUCTION Mexico is a leader and a referent in advanced manufacturing. It is also Latin America’s main exporter of medium and high technology. The country has created a favourable environment to attract investment and develop talent, which has allowed it to strengthen the necessary productive capacities to foster Mexican industries competitiveness both domestically and abroad. A key element to this process has been the ease with which new and superior tech- nologies are adopted, increasing the possibilities to create even greater value. -

Urban October 2020

URBAN OCTOBER REPORT 2020 URBAN OCTOBER REPORT 2020 I Table of Contents World Habitat Day’s Virtual Global Observance 1 Africa 4 Asia 8 Europe 15 Latin America and the Caribbean 17 North America 18 Oceania 20 World Cities Day’s Virtual Global Observance 22 Africa 24 Asia 28 Europe 38 Latin America and the Caribbean 40 North America 41 Oceania 44 Urban October Events 47 Africa 48 Asia 56 Europe 65 Latin America and the Caribbean 74 North America 104 Oceania 108 Statistics for World Habitat Day, World Cities Day and Urban October 109 List of World Habitat Day, World Cities Day and Urban October Celebrations around the world 110 II URBAN OCTOBER REPORT 2020 URBAN OCTOBER REPORT 2020 III WORLD HABITAT DAY Events IV URBAN OCTOBER REPORT 2020 WORLD HABITAT DAY’S VIRTUAL GLOBAL OBSERVANCE IN SURABAYA, INDONESIA World Habitat Day was celebrated on Monday 5 October 2020 with the theme Housing for All: A Better Urban Future. There were 69 events celebrated globally in 42 countries and 58 cities. The Global Observance of World Habitat He said the Housing for All theme was said everyone now realised that “housing Day co-hosted this year by UN-Habitat “the right agenda for all of us” as globally is an important need and pre condition and the Government of Indonesia, came a house is a basic need, adding that the for properly accessing needs such as from Surabaya, Indonesia combining Indonesian Government was trying hard to education and health.” dynamic physical meetings with global ensure everyone had decent housing.