By Kevin Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Letters Mingle Soules

Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) Volume 8 Issue 1 Syracuse Scholar Spring 1987 Article 2 5-15-1987 Letters Mingle Soules Ben Howard Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar Recommended Citation Howard, Ben (1987) "Letters Mingle Soules," Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991): Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar/vol8/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Howard: Letters Mingle Soules Letters Mingle Soules Si1; mure than kisses) letters mingle Soules; Fm; thus friends absent speake. -Donne, "To Sir Henry Wotton" BEN HOWARD EW LITERARY FORMS are more inviting than the familiar IF letter. And few can claim a more enduring appeal than that imi tation of personal correspondence, the letter in verse. Over the centu ries, whether its author has been Horace or Ovid, Dryden or Pope, Auden or Richard Howard, the verse letter has offered a rare mixture of dignity and familiarity, uniting graceful talk with intimate revela tion. The arresting immediacy of the classic verse epistles-Pope's to Arbuthnot, Jonson's to Sackville, Donne's to Watton-derives in part from their authors' distinctive voices. But it is also a quality intrinsic to the genre. More than other modes, the verse letter can readily com bine the polished phrase and the improvised excursus, the studied speech and the wayward meditation. The richness of the epistolary tradition has not been lost on con temporary poets. -

The Earth Says Have a Place William Stafford and a Place of Language

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Fall 2001 The Earth Says Have A Place William Stafford And A Place Of Language Thomas Fox Averill Washburn University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Averill, Thomas Fox, "The Earth Says Have A Place William Stafford And A Place Of Language" (2001). Great Plains Quarterly. 2181. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2181 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE EARTH SAYS HAVE A PLACE WILLIAM STAFFORD AND A PLACE OF LANGUAGE THOMAS FOX AVERILL In the spring of 1986, my daughter was almost NOTE four years old and my wife and I were to have poet William Stafford to dinner during a visit Straw, feathers, dust he made to Washburn University. I searched little things for a short Stafford poem our daughter might memorize as a welcome and a tribute. We came but if they all go one way, across this simple gem, and she spoke it to him that's the way the wind goes. at the table. -William Stafford, "Note," The Way It Is: New and Selected Poems (1998)1 Later in his visit, Stafford told a story about "Note." He traveled extensively all over the world. -

She Whose Eyes Are Open Forever”: Does Protest Poetry Matter?

commentary by JAMES GLEASON BISHOP “she whose eyes are open forever”: Does Protest Poetry Matter? ne warm June morning in 1985, I maneuvered my rusty yellow Escort over shin-deep ruts in my trailer park to pick up Adam, a young enlisted aircraft mechanic. Adam had one toddler and one newborn to Osupport. My two children were one and two years old. To save money, we carpooled 11 miles to Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, New York. We were on a flight path for B-52s hangared at Griffiss, though none were flying that morning. On the long entryway to the security gate, Adam and I passed a group of people protesting nuclear weapons on base. They had drawn chalk figures of humans in our lane along the base access road. Adam and I ran over the drawings without comment. A man. A pregnant woman. Two children—clearly a girl and boy. As I drove toward the security gate, a protestor with long sandy hair waved a sign at us. She was standing in the center of the road, between lanes. Another 15 protestors lined both sides of the roads, but she was alone in the middle, waving her tall, heavy cardboard sign with block hand lettering: WE DON’T WANT YOUR NUKES! A year earlier, I’d graduated from college and joined the Air Force. With my professors’ Sixties zeitgeist lingering in my mind, I smiled and waved, gave her the thumbs up. Adam looked away, mumbled, “Don’t do that.” After the gate guard checked our IDs, Adam told me why he disliked the protestors. -

Praying with William Stafford Presented by Jerry Williams Why I

Praying with William Stafford Presented by Jerry Williams Why I Am Happy Now has come, an easy time. I let it roll. There is a lake somewhere so blue and far nobody owns it. A wind comes by and a willow listens gracefully. I hear all this, every summer. I laugh and cry for every turn of the world, its terribly cold, innocent spin. That lake stays blue and free; it goes on and on. And I know where it is. ---- WILLIAM STAFFORD (1914–1993) was born in Hutchinson, Kansas. In his early years he worked a variety of jobs—in sugar beet fields, in construction, at an oil refinery—and received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Kansas. A conscientious objector and pacifist, he spent the years 1942–1946 in Arkansas and California work camps in the Civilian Public Service, fighting forest fires, building and maintaining trails and roads, halting soil erosion, and beginning his habit of rising early every morning to write. After the war he taught high school, worked for Church World Service, and joined the English faculty of Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, where he taught until his retirement. He received his PhD from the University of Iowa. He married Dorothy Hope Frantz in 1944, and they were the parents of four children. Stafford was the author of more than sixty books, the first of which, West of Your City, was published when he was forty-six. He received the 1963 National Book Award for Traveling through the Dark. He served as Poetry Consultant for the Library of Congress from 1970–1971 and was appointed Oregon State Poet Laureate in 1975. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Fire This Time a New Generation Speaks About Race by Jesmyn Ward the Fire This Time: a New Generation of Voices on Race

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Fire This Time A New Generation Speaks about Race by Jesmyn Ward The Fire This Time: A new generation of voices on race. A virtual roundtable conversation featuring Kima Jones, Kiese Laymon, Daniel José Older , and Emily Raboteau , four contributors to The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race edited by Jesmyn Ward. “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive.” — James Baldwin. James Baldwin’s seminal 1963 national bestseller The Fire Next Time includes “My Dungeon Shook — Letter to my Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of Emancipation.” In this letter, Baldwin tells his nephew that “the country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too soon.” Now, 50-plus years later, National Book Award winner Jesmyn Ward has brought together a group of 17 fellow writers to respond to the current state of affairs in our nation — extrajudicial killings by police and the protests that follow, and the fallacy that we’re living in a “post-racial” society. In The Fire This Time , these writers’ essays, memoirs, and poems explore the concept of freedom and the past, present and future of black lives in America. The Undefeated recently convened a virtual roundtable among four of the collection’s contributors to discuss art as disruption and what it means to be “a child of Baldwin.” The Undefeated : In the intro to The Fire This Time , Jesmyn Ward writes, ‘All these essays give me hope. -

Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents

Between the Covers - Rare Books, Inc. 112 Nicholson Rd (856) 456-8008 will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Gloucester City NJ 08030 Fax (856) 456-7675 PayPal. www.betweenthecovers.com [email protected] Domestic orders please include $5.00 postage for the first item, $2.00 for each item thereafter. Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in Overseas orders will be sent airmail at cost (unless other arrange- the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. ments are requested). All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are Members ABAA, ILAB. unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions Cover verse and design by Tom Bloom © 2008 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents: ................................................................Page Literature (General Fiction & Non-Fiction) ...........................1 Baseball ................................................................................72 African-Americana ...............................................................55 Photography & Illustration ..................................................75 Children’s Books ..................................................................59 Music ...................................................................................80 -

Poetry for the People

06-0001 ETF_33_43 12/14/05 4:07 PM Page 33 U.S. Poet Laureates P OETRY 1937–1941 JOSEPH AUSLANDER FOR THE (1897–1965) 1943–1944 ALLEN TATE (1899–1979) P EOPLE 1944–1945 ROBERT PENN WARREN (1905–1989) 1945–1946 LOUISE BOGAN (1897–1970) 1946–1947 KARL SHAPIRO BY (1913–2000) K ITTY J OHNSON 1947–1948 ROBERT LOWELL (1917–1977) HE WRITING AND READING OF POETRY 1948–1949 “ LEONIE ADAMS is the sharing of wonderful discoveries,” according to Ted Kooser, U.S. (1899–1988) TPoet Laureate and winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. 1949–1950 Poetry can open our eyes to new ways of looking at experiences, emo- ELIZABETH BISHOP tions, people, everyday objects, and more. It takes us on voyages with poetic (1911–1979) devices such as imagery, metaphor, rhythm, and rhyme. The poet shares ideas 1950–1952 CONRAD AIKEN with readers and listeners; readers and listeners share ideas with each other. And (1889–1973) anyone can be part of this exchange. Although poetry is, perhaps wrongly, often 1952 seen as an exclusive domain of a cultured minority, many writers and readers of WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS (1883–1963) poetry oppose this stereotype. There will likely always be debates about how 1956–1958 transparent, how easy to understand, poetry should be, and much poetry, by its RANDALL JARRELL very nature, will always be esoteric. But that’s no reason to keep it out of reach. (1914–1965) Today’s most honored poets embrace the idea that poetry should be accessible 1958–1959 ROBERT FROST to everyone. -

American Poetry Review Records Ms

American Poetry Review records Ms. Coll. 349 Finding aid prepared by Maggie Kruesi. Last updated on June 23, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2001 American Poetry Review records Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Other Finding Aids........................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Correspondence......................................................................................................................................10 APR Events and Projects..................................................................................................................... -

2018 Program

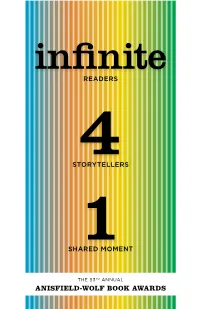

infinite READERS STORYTELLERS4 SHARED1 MOMENT THE 83RD ANNUAL ANISFIELD-WOLF BOOK AWARDS Since 1935, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards has recognized writers whose works confront racism and celebrate diversity. The prizes are given each year to outstanding books published in English the previous year. An independent jury of inter- nationally recognized scholars selects the winners. Since 1996, the jury has also bestowed lifetime achievement awards. Cleveland poet and philanthropist Edith Anisfield Wolf established the book awards in 1935 in honor of her family’s passion for social justice. Her father, John Anisfield, took great care to nurture his only child’s awareness of local and world issues. After a successful career in the garment and real estate industries, he retired early to devote his life to charity. Edith attended Flora Stone Mather College for Women and helped administer her father’s philanthropy. Upon her death in 1963, she left her home to the Cleveland Welfare Association, her books to the Cleveland Public Library, and her money to the Cleveland Foundation. Design: Nesnadny + Schwartz, www.NSideas.com 83 YEARS WELCOME TO THE 83RD ANNUAL ANISFIELD-WOLF BOOK AWARDS PRESENTED BY THE CLEVELAND FOUNDATION SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 KEYBANK STATE THEATRE WELCOME ACCEPTANCE Ronn Richard Shane McCrae President & Chief Executive Poetry Officer, Cleveland Foundation In the Language of My Captor YOUNG ARTIST PERFORMANCE Jesmyn Ward Eloise Xiang-Yu Peckham Fiction Read her poem on page 7 Sing, Unburied, Sing INTRODUCTION OF WINNERS Kevin Young Henry Louis Gates Jr. Nonfiction Chair, Anisfield-Wolf Book Bunk: Awards Jury The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Founding Director, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, Hutchins Center for African and and Fake News African American Research, Harvard University N. -

Click Here For

GRAYWOLF PRESS Nonprofit 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600 Organization Minnneapolis, Minnesota 55401 U.S. Postage Paid Twin Cities, MN ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED Permit No 32740 Graywolf Press is a leading independent publisher committed to the discovery and energetic publication of twenty-first century American and international literature. We champion outstanding writers at all stages of their careers to ensure that adventurous readers can find underrepresented and diverse voices in a crowded marketplace. FALL 2018 G RAYWOLF P RESS We believe works of literature nourish the reader’s spirit and enrich the broader culture, and that they must be supported by attentive editing, compelling design, and creative promotion. www.graywolfpress.org Graywolf Press Visit our website: www.graywolfpress.org Our work is made possible by the book buyer, and by the generous support of individuals, corporations, founda- tions, and governmental agencies, to whom we offer heartfelt thanks. We encourage you to support Graywolf’s publishing efforts. For information, check our website (listed above) or call us at (651) 641-0077. GRAYWOLF STAFF Fiona McCrae, Director and Publisher Yana Makuwa, Editorial Assistant Marisa Atkinson, Director of Marketing and Engagement Pat Marjoram, Accountant Jasmine Carlson, Development and Administrative Assistant Caroline Nitz, Senior Publicity Manager Mattan Comay, Marketing and Publicity Assistant Ethan Nosowsky, Editorial Director Chantz Erolin, Citizen Literary Fellow Casey O’Neil, Sales Director Katie Dublinski, Associate Publisher Josh Ostergaard, Development Officer Rachel Fulkerson, Development Consultant Susannah Sharpless, Editorial Assistant Karen Gu, Publicity Associate Jeff Shotts, Executive Editor Leslie Johnson, Managing Director Steve Woodward, Editor BOARD OF DIRECTORS Carol Bemis (Chair), Trish F. -

Jelly Roll by Kevin Young

Jelly Roll by Kevin Young Jelly Roll is the third volume of poetry published by Kevin Young, and it was a fnalist for the 2003 National Book Award. The lyrics in this collection are what Young calls “blues-based love poems”—sonically rich, stylized evocations full of delicious surprises. The book celebrates African American music history as it conjures up feld song, boogaloo, and jitterbug. Young expresses the real pain of heartbreak and hard times with wit, wordplay, and bemusement. This is a book that hurts so good. Selected by the Poet Laureate of Grand Rapids and the Poet Laureate Committee. About the Author: About the Author: Kevin Young’s writing has earned him many prestigious awards including the Patterson Poetry Prize, a Guggenheim grant, and the Greywolf Press Nonfction Prize. His frst book, Most Way Home, was a winner of the National Poetry Series. The New York Times has praised his poetry as “highly entertaining,” “often dazzling,” “compulsively readable.” He teaches creative writing at Emory University in Atlanta, where he curates the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library. Questions for Discussion 1. Where and in what way do you hear music in these poems? How would you describe them? 2. Young uses the technique of enjambment, the continuation of a sentence from one line of poetry to the next rather than stopping the sentence at the end of the poetic line. How does this technique transform the reading experience of the poems in Jelly Roll? Any poem in particular where enjambment enhances the effect? 3. What do these poems say about love, longing, lament? Three Poems that Deserve a Second Look “Blues,” “Swing,” and “Deep Song” More About Maurice Manning An interview at Failbetter: http://www.failbetter.com/33/YoungInterview.php From his author page at Blue Flower Arts: http://bluefowerarts.com/artist/kevin-young/ Jelly Roll by Kevin Young | Updated 01.2015 .