Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Fire This Time a New Generation Speaks About Race by Jesmyn Ward the Fire This Time: a New Generation of Voices on Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Program

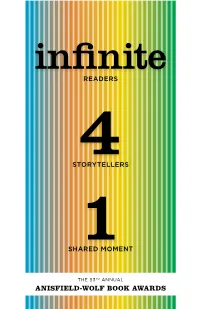

infinite READERS STORYTELLERS4 SHARED1 MOMENT THE 83RD ANNUAL ANISFIELD-WOLF BOOK AWARDS Since 1935, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards has recognized writers whose works confront racism and celebrate diversity. The prizes are given each year to outstanding books published in English the previous year. An independent jury of inter- nationally recognized scholars selects the winners. Since 1996, the jury has also bestowed lifetime achievement awards. Cleveland poet and philanthropist Edith Anisfield Wolf established the book awards in 1935 in honor of her family’s passion for social justice. Her father, John Anisfield, took great care to nurture his only child’s awareness of local and world issues. After a successful career in the garment and real estate industries, he retired early to devote his life to charity. Edith attended Flora Stone Mather College for Women and helped administer her father’s philanthropy. Upon her death in 1963, she left her home to the Cleveland Welfare Association, her books to the Cleveland Public Library, and her money to the Cleveland Foundation. Design: Nesnadny + Schwartz, www.NSideas.com 83 YEARS WELCOME TO THE 83RD ANNUAL ANISFIELD-WOLF BOOK AWARDS PRESENTED BY THE CLEVELAND FOUNDATION SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 KEYBANK STATE THEATRE WELCOME ACCEPTANCE Ronn Richard Shane McCrae President & Chief Executive Poetry Officer, Cleveland Foundation In the Language of My Captor YOUNG ARTIST PERFORMANCE Jesmyn Ward Eloise Xiang-Yu Peckham Fiction Read her poem on page 7 Sing, Unburied, Sing INTRODUCTION OF WINNERS Kevin Young Henry Louis Gates Jr. Nonfiction Chair, Anisfield-Wolf Book Bunk: Awards Jury The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Founding Director, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, Hutchins Center for African and and Fake News African American Research, Harvard University N. -

Click Here For

GRAYWOLF PRESS Nonprofit 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600 Organization Minnneapolis, Minnesota 55401 U.S. Postage Paid Twin Cities, MN ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED Permit No 32740 Graywolf Press is a leading independent publisher committed to the discovery and energetic publication of twenty-first century American and international literature. We champion outstanding writers at all stages of their careers to ensure that adventurous readers can find underrepresented and diverse voices in a crowded marketplace. FALL 2018 G RAYWOLF P RESS We believe works of literature nourish the reader’s spirit and enrich the broader culture, and that they must be supported by attentive editing, compelling design, and creative promotion. www.graywolfpress.org Graywolf Press Visit our website: www.graywolfpress.org Our work is made possible by the book buyer, and by the generous support of individuals, corporations, founda- tions, and governmental agencies, to whom we offer heartfelt thanks. We encourage you to support Graywolf’s publishing efforts. For information, check our website (listed above) or call us at (651) 641-0077. GRAYWOLF STAFF Fiona McCrae, Director and Publisher Yana Makuwa, Editorial Assistant Marisa Atkinson, Director of Marketing and Engagement Pat Marjoram, Accountant Jasmine Carlson, Development and Administrative Assistant Caroline Nitz, Senior Publicity Manager Mattan Comay, Marketing and Publicity Assistant Ethan Nosowsky, Editorial Director Chantz Erolin, Citizen Literary Fellow Casey O’Neil, Sales Director Katie Dublinski, Associate Publisher Josh Ostergaard, Development Officer Rachel Fulkerson, Development Consultant Susannah Sharpless, Editorial Assistant Karen Gu, Publicity Associate Jeff Shotts, Executive Editor Leslie Johnson, Managing Director Steve Woodward, Editor BOARD OF DIRECTORS Carol Bemis (Chair), Trish F. -

Jelly Roll by Kevin Young

Jelly Roll by Kevin Young Jelly Roll is the third volume of poetry published by Kevin Young, and it was a fnalist for the 2003 National Book Award. The lyrics in this collection are what Young calls “blues-based love poems”—sonically rich, stylized evocations full of delicious surprises. The book celebrates African American music history as it conjures up feld song, boogaloo, and jitterbug. Young expresses the real pain of heartbreak and hard times with wit, wordplay, and bemusement. This is a book that hurts so good. Selected by the Poet Laureate of Grand Rapids and the Poet Laureate Committee. About the Author: About the Author: Kevin Young’s writing has earned him many prestigious awards including the Patterson Poetry Prize, a Guggenheim grant, and the Greywolf Press Nonfction Prize. His frst book, Most Way Home, was a winner of the National Poetry Series. The New York Times has praised his poetry as “highly entertaining,” “often dazzling,” “compulsively readable.” He teaches creative writing at Emory University in Atlanta, where he curates the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library. Questions for Discussion 1. Where and in what way do you hear music in these poems? How would you describe them? 2. Young uses the technique of enjambment, the continuation of a sentence from one line of poetry to the next rather than stopping the sentence at the end of the poetic line. How does this technique transform the reading experience of the poems in Jelly Roll? Any poem in particular where enjambment enhances the effect? 3. What do these poems say about love, longing, lament? Three Poems that Deserve a Second Look “Blues,” “Swing,” and “Deep Song” More About Maurice Manning An interview at Failbetter: http://www.failbetter.com/33/YoungInterview.php From his author page at Blue Flower Arts: http://bluefowerarts.com/artist/kevin-young/ Jelly Roll by Kevin Young | Updated 01.2015 . -

December 17, 2008 for More Information

December 17, 2008 For More Information: Lea McLees, 404.727.0211, [email protected] Elaine Justice, 404.727.0643, [email protected] For Immediate Release KEVIN YOUNG NAMED CURATOR OF LITERARY COLLECTIONS For Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library Award-winning poet, editor and Emory professor Kevin Young today was named curator of literary collections for the Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library (MARBL). Young brings to the job the perspectives of a scholar, a writer and a teacher of writing, said Vice Provost and Director of Emory Libraries Rick Luce. “As a result of his experiences, Kevin understands the context in which manuscripts, archives and rare books are used,” Luce said. “On the scholarly side, he has deep knowledge of literary collections, both prose and poetry.” Young’s plans as literary collections curator include “focusing further on Emory’s diverse strengths in modern literature, particularly Irish, African American and British literature.” He also is interested in building an archive of poetry audio recordings to complement Emory’s already strong holdings in the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library Kevin Young and throughout MARBL. “I’m delighted to expand my role further in MARBL and at Emory,” Young said. “The collections are so international and inclusive already, with archives from Salman Rushdie to Lucille Clifton, that I am quite excited to continue that trajectory. Plus, it’s a real treat to be the curator working with the papers of Seamus Heaney, whom I studied with years ago.” Young’s international reputation stems from the six poetry collections he’s authored and four he’s edited. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 Lewis Skillman Klatt 1330 Logan Street SE Professor, English Department Grand Rapids, MI 49506 Calvin University (616) 204-2901 3201 Burton Street SE [email protected] Grand Rapids, MI 49546-4404 www.lsklatt.org (616) 526-7530 EDUCATION Ph.D., English, University of Georgia, Athens, GA M.A.L.A., St. John’s College, Annapolis, MD M.Div., Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Boston, MA B.A., English, Wittenberg University, Springfield, OH DISSERTATION THE GOD IS BLUE: A COLLECTION OF ORIGINAL POEMS WITH A MANIFESTO The introductory essay traces the idea of poetic energy as it is discussed in the American literary tradition and as it is manifest in my own aesthetic. AWARDS AND HONORS (Selected) Artist Fellow, The Hermitage Artist Retreat, Sarasota County, Florida, 2020-2021 Presidential Award for Exemplary Teaching, 2018 Poet Laureate of Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2014-2017 Winner, 2010 Iowa Poetry Prize (University of Iowa Press), Cloud of Ink Winner, 2008 Juniper Prize (University of Massachusetts Press), Interloper Finalist, 2016 Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize, Saturnalia Books, The Wilderness After Which Finalist, 2016 Green Rose Prize, New Issues Poetry & Prose, The Wilderness After Which Finalist, 2016 Snowbound Chapbook Award, Tupelo Press, The Corporation 2 Finalist, 2014 Green Rose Prize, New Issues Poetry & Prose, The Wilderness After Which Finalist, 2013 New Measures Poetry Prize, Free Verse Editions, Sunshine Wound Finalist, 2013 Green Rose Prize, New Issues Poetry & Prose, Sunshine Wound Finalist, 2013 Wabash Poetry Prize, Sycamore -

National African American Read-In

National African American Read-In NCTE Annual Convention attendees were asked to share their favorite book(s) written by an African American author. Africa Dream Eloise Greenfield After Tupac and D Foster Jacqueline Woodson The Amazing Things That Books Can Do Ryan Joiner Another Country James Baldwin Apex Hides the Hurt Colson Whitehead Assata: An Autobiography Assata Shakur The Autobiography of Malcolm X Malcolm X and Alex Haley The Battle of Jericho Sharon Draper Beloved Toni Morrison Black Boy Richard Wright The Bluest Eye Toni Morrison Bronx Masquerade Nikki Grimes Brown Girl Dreaming Jacqueline Woodson Bud, Not Buddy Christopher Paul Curtis Cane Jean Toomer The Collected Poems Lucille Clifton The Color of Water James McBride The Color Purple Alice Walker Copper Sun Sharon Draper The Crossover Kwame Alexander The Devil in Silver Victor LaValle Fences August Wilson The Fire Next Time James Baldwin Giovanni's Room James Baldwin The Grey Album Kevin Young Having Our Say Sarah L. Delany and A. Elizabeth Delany Head Off & Split Nikky Finney The History of White People Nell Irvin Painter I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Maya Angelou Incognegro Mat Johnson The Intuitionist Colson Whitehead Invisible Man Ralph Ellison Jelly Roll Kevin Young Just Mercy Bryan Stevenson Kindred Octavia E. Butler The Legend of Tarik Walter Dean Myers Locomotion Jacqueline Woodson Loving Day Mat Johnson Mama Day Gloria Naylor Meet Addy Connie Porter Of Mules and Men Zora Neale Hurston Out of My Mind Sharon Draper Parable of the Sower Octavia E. Butler Passing Nella -

YOUNG, KEVIN, 1970- Kevin Young Papers, 1976-2016

YOUNG, KEVIN, 1970- Kevin Young papers, 1976-2016 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Young, Kevin, 1970- Title: Kevin Young papers, 1976-2016 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1447 Extent: 101.375 linear feet (102 boxes), AV Masters: 0.25 linear foot (1 box), and 6.19 GB born digital material (8,950 files) Abstract: Papers of American poet Kevin Young, including writings, literary correspondence, photographs, printed material, audiovisual material, and born digital material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. The following material has been restricted until February 2028: nonliterary correspondence; manuscript of Colson Whitehead’s first, unpublished novel Return of the Spook and any of its drafts; and notebooks after 2005. Works in progress are restricted until publication. Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. -

By Kevin Young

AN ONLINE COLLECTION OF POETRY provided by the Ad Astra Poetry Project, Kansas Arts Commission, 2009 • "Childhood" by Kevin Young (January 20, 2009) • "At Cather's Grave" by Amy Fleury (February 09, 2009) • "Married to a Cowboy" by Jack DeWerff (March 02, 2009) • "Late Harvest" by James Vincent Tate (March 17, 2009) • "The Jackalope" by Gary J. Lechliter (March 20, 2009) • "Not A Regular Kansas Sermon" by Charles Plymell (April 26, 2009) • "Lightning's Bite" by Kevin James Rabas (June 02, 2009) • "Coyote Invades Your Dreams" by Linda Lynette Rodriguez (June 18, 2009) • "Columbarium Garden" by Denise Lea (Dotson) Low (June 30, 2009) • "Sunset" by Victor Contoski (July 21, 2009) • "Yearly Restoration" by Serina Allison Hearn (August 16, 2009) • "Spider" by Donald Warren Levering (September 14, 2009) • "From Angle Of Yaw" by Benjamin S. Lerner (October 14, 2009) • "Watching the Kansas River" by Elizabeth Avery Schultz (November 11, 2009) • "My Advice" by Stephen E. Meats (December 07, 2009) KEVIN YOUNG (1970 - ) “IK evinthink Young, there’s born a in lot Nebraska, of interesting spent middle history and highregarding school in Kansas,Topeka before both attending its history Harvard as aUniversity. state and He being is a professor a free at Emorystate, University and also in just Atlanta, in general and he itsis acultural renowned history poet and editor. He has won Guggenheim, NEA, and Stegner Fellowships. Young was once a student of mine in a summer creative writing workshop for middle school students at Washburn University. When he was still a teenager, Thomas Fox Averill of Washburn sponsored Young to edit a book of poetry by Kansas poet Edgar Wolfe. -

Book of Hours by Kevin Young

Book of Hours by Kevin Young 1 Table of Contents Book of Hours About the Book .................................................... 3 “Not the storm About the Author ................................................. 4 Discussion Questions ............................................ 5 but the calm Credits ................................................................ 7 that slays me.” Preface Lauded today as "one of the poetry stars of his generation" (Los Angeles Times), Kevin Young is an NEA fellow and award-winning author of 11 books of poetry and prose. In Book of Hours, Kevin chronicles and links two profound life experiences: the death of his father and the birth of his son. Named one of the "ten essential poetry titles for 2014" by Library Journal, the book's themes are universally resonant, its poems at once intimate and relatable. "If you read no other book of poetry this year, this should be the one" (Atlanta Journal-Constitution). "I've read plenty of books about grief and about coming through grief in my life, but I've never before encountered a book that gets it as right as Kevin Young's Book of Hours," writes The Stranger. "It's one of those rare reading experiences that I recognized, even as What is the NEA Big Read? I read it, as a book I was going to buy over and over again, to give as a gift to friends who've had that certain hole cut A program of the National Endowment for the Arts, NEA Big out of them, the loss that you can recognize from a distance, Read broadens our understanding of our world, our even in the happiest of times." communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a good book. -

Major Jackson

major jackson Office: University of Vermont Department of English 400 Old Mill Burlington, VT 05405 802-656-2221 (office) [email protected] www.majorjackson.com PUBLICATIONS Collections of Poetry The Absurd Man. W.W. Norton, April 2020. Roll Deep. W.W. Norton, August 2015. Holding Company. W.W. Norton, Summer 2010. Hoops. W.W. Norton, Winter 2006. Leaving Saturn: Poems. University of Georgia Press, Winter 2002. Anthologies Best American Poetry, 2019 (Editor), Series Editor David Lehman, Scribner’s, September, 2019. Renga for Obama: An Occasional Poem (Editor), Houghton Library and President & Fellows at Harvard University, March, 2018. The Collected Poems of Countee Cullen (Editor). Library of America, Summer 2013. Miscellany Leave It All Up to Me (New York Subway Poster), Metropolitan Transportation Authority & Poetry Society of America, 2017. The Sweet Hurried Trip Under an Overcast Sky. Floating Wolf Quarterly, Fall, 2013. (online chapbook) Essays & Articles The Paris Review, “On Romance and Francesca DiMattio,” Spring 2019 American Poet, “Books Noted:” Reviews of books by Terrance Hayes, Tracy K. Smith, Kevin Young, Brenda Hillman, Forrest Gander, Li-Young Lee, Carmen Gimenez Smith, Dorothea Lasky, Marcelo Castillo, Hieu Minh Nguyen, Bim Ramke. Spring, 2018. World Literature Today, “’Every Poet Has to Be Lonely’: A Conversation with Tomasz Różycki and His Translators” September 2016. Guernica Magazine, “Where Scars Reside” April 2016. Boston Review (Online), “On Countee Cullen.” February 2013. Harvard Divinity Bulletin, “Listen Children: An Appreciation of Lucille Clifton.” Winter/Spring 2012. American Poet, “The Historical Poem.” Fall 2008. American Poetry Review, “A Mystical Silence: Big and Black.” September/October 2007. Poetry, “Social Function of Poetry.” January 2007. -

Lesson Plan Bunk: the Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News

Lesson Plan Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News By Kevin Young Developed by Cara Byrne, PhD Sara Fuller, PhD Kristine Kelly, PhD Shared on behalf of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards Teaching Kevin Young’s Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News Anisfield-Wolf Lesson Plan This lesson plan provides background information, discussion questions, key quotations and activities to help explore Kevin Young’s 2018 Anisfield-Wolf Award-winning book, Bunk. Developed by Cara Byrne, PhD, Lecturer in English at Case Western Reserve University Sara Fuller, PhD, Assistant Professor of English at Cuyahoga Community College Kristine Kelly, PhD, Lecturer in English at Case Western Reserve University Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News Background: Kevin Young (b. 1970) was born in Nebraska and studied poetry at Harvard, Brown and Stanford. As of December 2020, he has written fourteen books of poetry and essays, including Book of Hours (2014) and Jelly Roll: A Blues (2003). He is the poetry editor for The New Yorker and served as the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture from 2016 - 2020. He also spent 11 years as a professor of creative writing and English at Emory University in Atlanta. In 2020, he was named the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. He will begin serving in this role in January 2021. He was also named a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2020.1 Young’s first book of nonfiction, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness, was published in 2012. -

Major Jackson

major jackson Office: University of Vermont Department of English 400 Old Mill Burlington, VT 05405 802-656-2221 (office) [email protected] [email protected] www.majorjackson.com PUBLICATIONS Books Renga for Obama: An Occasional Poem (Editor), Houghton Library and President & Fellows at Harvard University, March, 2018. Leave It All Up to Me (New York Subway Poster), Metropolitan Transportation Authority & Poetry Society of America, 2017. Roll Deep. W.W. Norton, August, 2015. The Collected Poems of Countee Cullen (Editor). Library of America, Summer 2013. Holding Company. W.W. Norton, Summer 2010. Hoops. W.W. Norton, Winter 2006. Leaving Saturn: Poems. University of Georgia Press, Winter 2002. The Sweet Hurried Trip Under an Overcast Sky. Floating Wolf Quarterly, Fall, 2013. (online chapbook) Essays & Articles American Poet, “Books Noted:” Reviews of books by Terrance Hayes, Tracy K. Smith, Kevin Young, Brenda Hillman, Forrest Gander, Li-Young Lee, Carmen Gimenez Smith, Dorothea Lasky, Marcelo Castillo, Hieu Minh Nguyen, Bim Ramke. Spring, 2018. World Literature Today, “’Every Poet Has to Be Lonely’: A Conversation with Tomasz Różycki and His Translators” September 2016. Guernica Magazine, “Where Scars Reside” April 2016. Boston Review (Online), “On Countee Cullen.” February 2013. Harvard Divinity Bulletin, “Listen Children: An Appreciation of Lucille Clifton.” Winter/Spring 2012. American Poet, “The Historical Poem.” Fall 2008. American Poetry Review, “A Mystical Silence: Big and Black.” September/October 2007. Poetry, “Social Function of Poetry.” January 2007. Poets & Writers, “Tales of the Heroic.” Jan/Feb 2002. Book Reviews New York Times Book Review, “Five Decades of Frank Bidart’s Verse, From Masks to Self- Mythology” October 4, 2017.