Epic Aging the Two Homeric Epics in Received Form (That Is, with Controverted Odyssey 24 Included) and Virgil's Aeneid Treat A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essay 2 Sample Responses

Classics / WAGS 23: Second Essay Responses Grading: I replaced names with a two-letter code (A or B followed by another letter) so that I could read the essays anonymously. I grouped essays by levels of success and cross-read those groups to check that the rankings were consistent. Comments on the assignment: Writers found all manner of things to focus on: Night, crying, hospitality, the return of princes from the dead (Hector, Odysseus), and the exchange of bodies (Hector, Penelope). Here are four interesting and quite different responses: Essay #1: Substitution I Am That I Am: The Nature of Identity in the Iliad and the Odyssey The last book of the Iliad, and the penultimate book of the Odyssey, both deal with the issue of substitution; specifically, of accepting a substitute for a lost loved one. Priam and Achilles become substitutes for each others' absent father and dead son. In contrast, Odysseus's journey is fraught with instances of him refusing to take a substitute for Penelope, and in the end Penelope makes the ultimate verification that Odysseus is not one of the many substitutes that she has been offered over the years. In their contrasting depictions of substitution, the endings of the Iliad and the Odyssey offer insights into each epic's depiction of identity in general. Questions of identity are in the foreground throughout much of the Iliad; one need only try to unravel the symbolism and consequences of Patroclus’ donning Achilles' armor to see how this is so. In the interaction between Achilles and Priam, however, they are particularly poignant. -

Homer and Greek Epic

HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) • The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Overview of The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Analysis of Book 24: The Death-Journey of Priam •Grammar 4: Review of Parts of Speech: Nouns, Verbs, Adjectives, Adverbs, Pronouns, Prepositions and Conjunctions HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 23 • Achilles holds funeral games in honor of Patroclus • these games serve to reunite the Greeks and restore their sense of camaraderie • but the Greeks and Trojans are still at odds • Achilles still refuses to return Hector’s corpse to his family HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles’ anger is as yet unresolved • the gods decide he must return Hector’s body • Zeus sends Thetis to tell him to inform him of their decision • she finds Achilles sulking in his tent and he agrees to accept ransom for Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • the gods also send a messenger to Priam and tell him to take many expensive goods to Achilles as a ransom for Hector’s body • he sneaks into the Greek camp and meets with Achilles • Achilles accepts Priam’s offer of ransom and gives him Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles and Priam arrange an eleven-day moratorium on fighting -

The Father-Son Relationship in the Iliad: the Case of Priam- Hector Introduction

Tsoutsouki, C. (2014); The Father-Son Relationship in the Iliad: The Case of Priam- Hector Introduction Rosetta 16: 78 – 92 http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue16/tsoutsouki.pdf The Father-Son Relationship in the Iliad: The Case of Priam-Hector Introduction Christiana Tsoutsouki It is widely accepted that the Iliad is not merely a tale of the Trojan War and its battles, but also a literary product that yields interesting insights into the nature of human interactions. Arguably, one of the most prominent expressions of these interactions is the father-son relationship, through which the epic narrative keeps constantly at the background the existence of a world beyond the battlefield, where fathers and sons engage in a tense and intimate interaction characterised by mutual feelings of love, affection, concern, and, most importantly, interdependency. The significance of the Iliadic father-son relationship has already been noted by a number of scholars. Greene (1970) was the first to draw attention to this topic by aptly characterising the Iliad as ‘a great poem of fatherhood’, and a few years later Lacey observed ‘how completely family-centred the society of Homeric poems is’ (1968: 34). Likewise, Redfield (1975), and Finlay (1980) examined the prevalence of the father- son bond in the epic narrative, while Griffin (1980) focused on the theme of the bereaved parents. Crotty (1994) dealt with different epic pairs of fathers and sons, being particularly concerned with the standards that the former impose on the latter. Interestingly, Ingalls (1998) centred on the attitudes towards children in the epic and argued for their high value in the Homeric society. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Study Questions Helen of Troycomp

Study Questions Helen of Troy 1. What does Paris say about Agamemnon? That he treated Helen as a slave and he would have attacked Troy anyway. 2. What is Priam’s reaction to Paris’ action? What is Paris’ response? Priam is initially very upset with his son. Paris tries to defend himself and convince his father that he should allow Helen to stay because of her poor treatment. 3. What does Cassandra say when she first sees Helen? What warning does she give? Cassandra identifies Helen as a Spartan and says she does not belong there. Cassandra warns that Helen will bring about the end of Troy. 4. What does Helen say she wants to do? Why do you think she does this? She says she wants to return to her husband. She is probably doing this in an attempt to save lives. 5. What does Menelaus ask of King Priam? Who goes with him? Menelaus asks for his wife back. Odysseus goes with him. 6. How does Odysseus’ approach to Priam differ from Menelaus’? Who seems to be more successful? Odysseus reasons with Priam and tries to appeal to his sense of propriety; Menelaus simply threatened. Odysseus seems to be more successful; Priam actually considers his offer. 7. Why does Priam decide against returning Helen? What offer does he make to her? He finds out that Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter for safe passage to Troy; Agamemnon does not believe that is an action suited to a king. Priam offers Helen the opportunity to become Helen of Troy. 8. What do Agamemnon and Achilles do as the rest of the Greek army lands on the Trojan coast? They disguise themselves and sneak into the city. -

Metempsychosis in Aeneid Six Author(S): E

Metempsychosis in Aeneid Six Author(s): E. L. Harrison Reviewed work(s): Source: The Classical Journal, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Feb. - Mar., 1978), pp. 193-197 Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3296685 . Accessed: 12/02/2013 21:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Tue, 12 Feb 2013 21:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions METEMPSYCHOSISIN AENEID SIX The purposeof this note is to suggest that, in orderto understandmore clearly the lines in which Virgil preparesthe way for his paradeof heroes in Book Six (679-755), we need to appreciatethe difficulties presentedby the introduction of such an episode, and consider how he handled them.' Although we can only surmise, it seems highly probablethat, influencedby the practice at the funerals of prominentRomans of having relatives walk in processionwearing portrait-masks of the dead man's ancestors,2Virgil decided to stage a similar spectacle on a granderscale, including in its scope the great figures of Rome's past. -

The Tale of Troy

THE TALE OF TROY WITH THE PUBLISHERS' COMPLIMENTS. THE TALE OF TROY DONE INTO ENGLISH BY AUBREY STEWART, M.A. LATE FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. ^London MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1886 D CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE i. How Paris carried off Helen . i ii. How the Heroes gathered at Aulis 13 in. How Achilles quarrelled with Agamemnon . 27 iv. How Paris fought Menelaus . 45 v. How Hector fought Ajax . .61 vi. How Hector tried to burn the Ships 87 vii. How Patroclus lost the Arms of Achilles . .109 vni. How Achilles slew Hector . .129 ix. How the Greeksfought the Amazons 147 x. How Paris slew Achilles . .167 xi. How Philoctetes slew Paris . 193 xn. How the Greeks took Troy . .215 HOW PARIS CARRIED OFF HELEN B CHAPTER I g earned off upon a time there lived a king ONCEand queen, named Tyndareus and Leda. Their home was Sparta, in the plea- sant vale of Laconia, beside the river Eurotas. They had four children, and these were so beautiful that men doubted whether they were indeed born of mortal parents. Their two sons were named Castor and Polydeuces. As they grew up, Castor became a famous horseman, and Polydeuces was the best boxer of his time. Their elder daughter, Clytem- nestra, was wedded to Agamemnon the son of Atreus, king of Mycenae, who was the greatest prince of his age throughout all the land of Hellas. Her sister Helen was the The Tale of Troy CHAP. loveliest woman ever seen upon earth, and every prince in Hellas wooed her for his bride; yet was her beauty fated to bring sorrow and destruction upon all who looked upon her. -

The Three Movements of the Iliad Heiden, Bruce Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Spring 1996; 37, 1; Proquest Pg

The three movements of the Iliad Heiden, Bruce Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Spring 1996; 37, 1; ProQuest pg. 5 The Three Movements of the Iliad Bruce Heiden HE ILIAD FOR US is a text to be read; for its composer, his audiences, and several generations of audiences after them, T it was a live vocal performance. Scholars of Greek epic and related genres have become increasingly sensitive to the losses in affect and significance that occur when such a per formance survives only in the form of its 'libretto'.! But for students of Homer the desire to recapture the power of the per formed Iliad confronts the silence of the historical record: the first traces of performances of Homer date from the mid-sixth century, perhaps more than a century after the epic's compo sition.2 Denys Page probably spoke for many in declining to speculate about how the questions concerning Homeric per formance might be answered. 3 Others have been less cautious. The issue of the performance structure of the Iliad has proven an especially fertile ground of speculation, because the evident 1 For recent theoretical discussion of these losses and efforts to recuperate them, see J. M. Foley, The Singer of Tales in Performance (Bloomington 1995) 1-59. 2 The view that our Iliad is the result of a major revision that occurred in sixth-century Athens has gained adherents during the past two decades: M. S. Jensen, The Homeric Question and the Ora/-Formulaic Theory (Copenhagen 1980); K. STANLEY, The Shield of Homer (Princeton 1993: hereafter 'Stanley') 279-93; R. -

01. Pelling, Homer and Question

Histos Supplement ( ) – HOMER AND THE QUESTION WHY * Christopher Pelling Abstract : Historiography’s debt to Homer is immense, especially in exploring matters of cause and effect. The epics trace things back to beginnings, even if those are only ‘hinges’ in a still longer story; they use speech-exchanges not merely to characterise individuals but also to explore features of their society; the interaction of human and divine is complex, but the narrative focus characteristically rests more on the human level; allusiveness to narratives of earlier and later events also carries explanatory value. Epic and historiography alike also cast light on why readers find such aesthetic pleasure in stories of suffering, brutality, and death. Keywords: Homer, historiography, causation, explanation, intertextuality. t is no secret, and no surprise, that Greek historiography is steeped in Homer: how could it not be so? Epic was the great genre for the sweep Iof human experience, especially but not only in war; Homer was the narrator supreme. There have been many studies of the ways that individual historians exploit Homer to add depth to their work. I have contributed one myself on Herodotus, 1 Maria Fragoulaki writes in this volume on Thucydides, and others have covered writers down to and including the Second Sophistic. 2 Still, when completing a monograph on historical explanation in Herodotus,3 I was struck even more forcefully than before by how many of the characteristic interpretative techniques—not merely what they do, but how they do it—are already there in the Iliad and Odyssey. As the similarity of title shows, this paper is a companion piece to that book, though a full treatment would itself have swollen to monograph proportions, and the points have relevance to many other historical writers as well as Herodotus. -

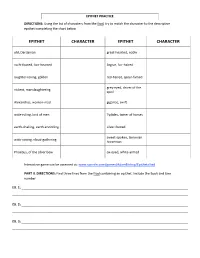

Epithet Character Epithet Character

EPITHET PRACTICE DIRECTIONS: Using the list of characters from the Iliad , try to match the character to the descriptive epithet completing the chart below EPITHET CHARACTER EPITHET CHARACTER old, Dardanian great-hearted, noble swift-footed, lion-hearted Argive, fair-haired laughter-loving, golden red-haired, spear-famed grey-eyed, driver of the violent, manslaughtering spoil Alexandros, woman-mad gigantic, swift wide-ruling, lord of men Tydides, tamer of horses earth-shaking, earth-encircling silver-footed sweet-spoken, Gerenian wide-seeing, cloud-gathering horseman Phoebus, of the silver bow ox-eyed, white-armed Interactive game can be accessed at: www.sporcle.com/games/AdamBishop/EpithetsIliad PART II. DIRECTIONS: Find three lines from the Iliad containing an epithet. Include the Book and Line number EX. 1: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________________ EX. 2: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________________ EX. 3: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction to the Dactylic Hexameter The Tradition of the Dactylic Hexameter: Before plunging into the technical details, a few introductory words -

The Trojan War

THE TROJAN WAR PART ONE: THE ORIGINS OF THE TROJAN WAR have actually revealed weaker stonework on the western walls of Troy, suggesting that a genuine difference in construction led to the myth that The city of Troy had several mythical founders and kings, the two gods built the other walls. including Teucer, Dardanus, Tros, Ilus and Assaracus. The most widely accepted story makes Ilus the actual founder, Mythical reasons behind the Trojan War and from him the city took the name it was best-known by in ancient times, Ilium. In an episode similar to the founding During Priam's of Thebes, Ilus was given a cow and told to found a city lifetime Troy where it first lay down. As instructed, he followed the reached its animal, and on the land where it rested drew up the greatest boundaries of his city. He then received an additional sign prosperity, but from the gods, a legless wooden statue called the Palladium, when he was a which dropped from the heavens with the message that it very old man it should be carefully guarded as it 'brought empire'. Some say was tota lly it was a statue of Athene's friend Pallas, but most believe it destroyed after a was of Athene herself and that this statue was to make Troy ten-year siege by a great city. warriors from Greece. Some say Laomedon's Troy Zeus himself Ilus was succeeded by his son Laomedon, who built great caused the Trojan walls around his city with the help of a mortal, Aeacus, and War to thin out the two gods Poseidon and Apollo. -

Ap Latin Summer Assignment

AP LATIN SUMMER ASSIGNMENT: Cardinal Gibbons High School Magistra Crabbe: 2018/2019 Assignment: Read and prepare for a test on Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Directions: ● Carefully read the introduction to the Aeneid written by Bernard Knox, and fill out the corresponding reflection questions. These questions will be collected and graded in August. Content from the introduction will be represented on the test in August. ● Carefully read the English Portions of the Syllabus from Virgil’s Aeneid. This is the entirety of Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Students should read the Revised Penguin Edition by David West. Hard copies of this book are available from Mrs. Crabbe in room 211. ● Fill out the corresponding study questions for each book. In August, these study questions will be collected and graded. ● Students will take a test on these readings before beginning the Latin portion of the AP Syllabus. Index of This Document: Introduction to the Aeneid by Bernard Knox: pp 126 Reading Questions for Introduction: pp 2734 Book I Reading Questions: pp 3543 Book II Reading Questions: pp 4449 Book IV Reading Questions: pp 5056 Book VI Reading Questions: pp 5764 Book VIII Reading Questions: pp 6568 Book XII Reading Questions: pp 6974 Suggested Reading Schedule: May 28th June 1st: Relax this week and recover from your finals. Drink lots of water. Get plenty of sleep. Spend time outside and do something fun with your friends. Help your parents around the house.