In Early Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward “Kid” Ory

Edward “Kid” Ory Mr. Edward “Kid” Ory was born in Woodland Plantation near La Place, Louisiana on December 25, 1886. As a child he started playing music on his own homemade instruments. He played the banjo during his youth but his love was playing the trombone. However, the banjo helped him develop “tailgate” a particular style of playing the trombone. By the time he was a teenager, Ory was the leader of a well-regarded band in southeast Louisiana. In his early twenty’s, he moved to New Orleans with his band where he became one of the most talented trombonists of early jazz from 1912 to 1919. In 1919, Ory relocated to Los Angeles, California for health reasons. He assembled a new group of New Orleans musicians on the West Coast and played regularly under the name of Kid Ory’s Creole Orchestra. There, he recorded the 1920s classics “Shine,” “Tiger Rag,” “Muskrat Ramble,” and “Maryland, My Maryland.” In 1922, he became the first African American jazz bank from New Orleans to record a studio album. In 1925, Ory moved to Chicago and took interest in working on radio broadcasts and recording with names such musicians as Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Johnny Dodds, and many others. During the Great Depression, Ory left music but returned in 1943 to lead one of the top New Orleans style bands of the period until 1961. It was about 1966 when Ory retired and spent his last years in Hawaii. He did, however, play occasionally for special events. One of his last performances was in 1971 when he surprised everyone by coming back to the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

North Carolina Jazz Repertory Orchestra with Special Guest Branford Marsalis Jim Ketch, Director

north carolina Jazz repertory orchestra withspecialguest branfordmarsalis Jim ketch, Director TUESDAY, APRIL 23, 7:30 PM BEASLEY-CURTIS AUDITORIUM, MEMORIAL HALL STUDENT TICKET ANGEL FUND BENEFACTORS Sharon and Doug Rothwell Jim Ketch, Music Director Saxophones Aaron Hill, Keenan This evening’s program will be announced from the stage. McKenzie, Gregg Gelb, Dave Finucane, Dave Reid Trombones Lucian Cobb, Wes T WAS RIGHT AROUND the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve Parker, Evan Ringel, Mike Kris 1993 at the Pinehurst resort. The eight-piece Gregg Gelb Swing Trumpets Jerry Bowers, Benjy Band was on its last break of the night, and, as trumpeter Jim Ketch I Springs, LeRoy Barley, Jim Ketch recalls, “Somebody said, ‘Man, wouldn’t it be great if we could augment Piano Ed Paolantonio this group with enough players to have a big band, and play music like Duke Guitar Marc Davis Ellington, Count Basie, and Benny Goodman?’” A few years earlier, Wynton Bass Jason Foureman Marsalis had founded the big band that would become the Jazz at Lincoln Drums Stephen Coffman Center Orchestra, and big band sounds were very much in the air. Inspired, Vocals Kathy Gelb Ketch and his compatriots quickly brainstormed a list of players who might be interested, and thus was born the North Carolina Jazz Repertory Orchestra. 48 ticket services 919.843.3333 NORTH CAROLINA JAZZ REPERTORY ORCHESTRA Twenty-five years, three albums, or her palette,” Ketch observes. “He sees them trawling through their and hundreds of concerts across wasn’t after trumpet three or trumpet extensive knowledge of Ellington the state of North Carolina later, the one; he’s after somebody who’s got and Strayhorn’s songbook to pick a seventeen-piece group, with Ketch a sound personality.” In Strayhorn, representative set of tunes. -

Chapter Outline

CHAPTER SIX: “IN THE MOOD”: THE SWING ERA, 1935–1945 Chapter Outline I. Swing Music and American Culture A. The Swing Era: 1935–45 1. Beginning in 1935, a new style of jazz-inspired music called “swing” transformed American popular music. 2. Initially developed in the late 1920s by black dance bands in New York, Chicago, and Kansas City 3. The word “swing” (like “jazz,” “blues,” and “rock ’n’ roll”) derives from African American English. a) First used as a verb for the fluid, rocking rhythmic momentum created by well-played music, the term was used by extension to refer to an emotional state characterized by a sense of freedom, vitality, and enjoyment. b) References to “swing” and “swinging” are common in the titles and lyrics of jazz records made during the 1920s and early 1930s. c) Around 1935, the music industry began to use “swing” as a proper noun—the name of a defined musical genre. 4. Between 1935 and 1945, hundreds of large dance orchestras directed by celebrity bandleaders dominated the national hit parade: 1 CHAPTER SIX: “IN THE MOOD”: THE SWING ERA, 1935–1945 a) Benny Goodman b) Tommy Dorsey c) Duke Ellington d) Count Basie e) Glenn Miller 5. These big bands appeared nightly on radio, their performances transmitted coast to coast from hotels and ballrooms in the big cities. 6. Their music was featured on jukeboxes. 7. Many of the bands crisscrossed the country in buses, playing for dances and concerts at local dance halls, theaters, and colleges. 8. The big bands were essentially a big-city phenomenon, a symbol of sophistication and modernity. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Benjamin Tucker

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Benjamin Tucker PERSON Tucker, Ben, 1930- Alternative Names: Benjamin Tucker; Life Dates: December 13, 1930-June 4, 2013 Place of Birth: Brentwood, Tennessee, USA Residence: Savannah, GA Occupations: Radio Entrepreneur; Jazz Bassist Biographical Note Noted jazz musician Benjamin Mayor Tucker was born on December 13, 1930 in Brentwood, Tennessee. Tucker and his twin brother grew up in Nashville with their parents Carrie Clayborne and Joseph Tucker. He graduated from Pearl High School in 1946 and matriculated at Tennessee State University in 1949 as a music major. In 1950, he joined the United States Air Force, serving for four years. Tucker’s love for music began at an early age. He taught himself to play the tuba at the age of thirteen and later the bass violin and piano. Some of his favorite jazz musicians included Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson. In 1956, Tucker moved to Hollywood, California, where he met Warren Marsh. His first recording was a collaboration with Marsh entitled Jazz of Two Cities in 1959. That same year, Metronome magazine named him one of the world’s top ten bass players. In 1961, he recorded Coming Home Baby, a hit for Herbie Mann and Mel Torme. This song was featured in the film Get Shorty. Tucker became Savannah, Georgia’s first African American radio station owner in 1972 when he purchased WSOK Radio. WSOK was the top AM station for thirteen years. His station had over 400,000 listeners and a reputation of integrity in advertising. In 1989, Tucker opened Hard Hearted Hannah’s, a jazz club. -

BC with Henri Chaix and His Orchestra

UPDATES TO VOLUME 2, BENNY CARTER: A LIFE IN AMERICAN MUSIC (2nd ed.) As a service to purchasers of the book, we will periodically update the material contained in Vol. 2. These updates follow the basic format used in the book’s Addendum section (pp. 809-822), and will include 1) any newly discovered sessions; 2) additional releases of previously listed sessions (by session number); 3) additional recordings of Carter’s arrangements and compositions (by title); 4) additional releases of previously listed recordings of Carter’s arrangements and compositions (by artist); 5) additional recorded tributes to Carter and entire albums of his music; and 6) additional awards received by Carter. We would welcome any new data in any of these areas. Readers may send information to Ed Berger ([email protected]). NOTE: These website additions do not include those listed in the book’s Addendum Section One (Instrumentalist): Additional Issues of Listed Sessions NOTE: All issues are CDs unless otherwise indicated. BC = Benny Carter Session #25 (Chocolate Dandies) Once Upon a Time: ASV 5450 (The Noble Art of Teddy Wilson) I Never Knew: Columbia River 220114 (Jazz on the Road) [2 CDs] Session #26 (BC) Blue Lou: Jazz After Hours 200006 (Best of Jazz Saxophone)[2 CDs]; ASV 5450 (The Noble Art of Teddy Wilson); Columbia River 120109 (Open Road Jazz); Columbia River 120063 (Best of Jazz Saxophone); Columbia River 220114 (Jazz on the Road) [2 CDs] Session #31 (Fletcher Henderson) Hotter Than ‘Ell: Properbox 37 (Ben Webster, Big Ben)[4 CDs] Session #33 (BC) -

King Porter Stomp" and the Jazz Tradition* Jazz Historians Have Reinforced and Expanded Morton's Claim and Goodman's Testimony

JEFFREY MAGEE 23 "King Porter Stomp" and the Jazz Tradition* Jazz historians have reinforced and expanded Morton's claim and Goodman's testimony. The Palomar explosion and its aftershocks have By Jeffrey Magee led some historians to cite it as the birth of the Swing Era, most notably Marshall W. Stearns, who, after tracing jazz's development in 1930-34, could simply assert, "The Swing Era was born on the night of 21 August 1935" (Stearns 1956:211; see echoes of this statement in Erenberg Fletcher won quite a few battles of music with "King Porter Stomp." 1998:3-4, and Giddins 1998:156). Gunther Schuller has called "King And Jelly Roll Morton knew this, and he used to go and say "I made Porter Stomp" one of the "dozen or so major stations in the development Fletcher Henderson." And Fletcher used to laugh . and say "You of jazz in the twenty years between 1926 and 1946" (Schuller 1989:840). did," you know. He wouldn't argue. (Henderson 1975, 1:69) And Goodman's recording, he wrote elsewhere, "was largely responsible for ushering in the Swing Era" (Schuller 1985). One of Morton's many Toward the end of his life in May 1938, Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton recordings of "King Porter Stomp" appeared on the canon-shaping (1890-1941) walked into the Library of Congress's Coolidge Auditorium Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz (now out of print), and Henderson's sporting an expensive suit, a gold watch fob and rings, and a diamond- and Goodman's versions may be found on the Smithsonian's Big-Band Jazz studded incisor (Lomax 1993:xvii). -

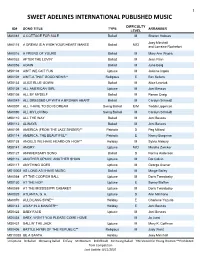

Published Music List

1 SWEET ADELINES INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHED MUSIC DIFFICULTY ID# SONG TITLE TYPE ARRANGER LEVEL MA0081 A COTTAGE FOR SALE Ballad M Sharon Holmes Joey Minshall MA0115 A DREAM IS A WISH YOUR HEART MAKES Ballad M/D and Lorraine Rochefort MA0016 A FRIEND OF YOURS Ballad M Mary Ann Wydra MA0032 AFTER THE LOVIN' Ballad M Jean Flinn MA0056 AGAIN Ballad M June Berg MS0103 AIN'T WE GOT FUN Uptune M JoAnne Ingels MS0101 AIN'T-A THAT GOOD NEWS** Religious E Bev Sellers MS0133 ALICE BLUE GOWN Ballad M Alice Lesniak MS0126 ALL AMERICAN GIRL Uptune M Joni Bescos MS0108 ALL BY MYSELF Ballad M Renee Craig MA0049 ALL DRESSED UP WITH A BROKEN HEART Ballad M Carolyn Schmidt MA0007 ALL I HAVE TO DO IS DREAM Swing Ballad E/M Tedda Lippincott MA0090 ALL MY LOVING Swing Ballad M Carolyn Schmidt MS0110 ALL THE WAY Ballad M Joni Bescos MS0112 ALWAYS Ballad M Joni Bescos MA0109 AMERICA (FROM THE JAZZ SINGER)** Patriotic D Peg Millard MS0114 AMERICA, THE BEAUTIFUL** Patriotic E Nancy Bergman MS0138 ANGELS WE HAVE HEARD ON HIGH** Holiday M Sylvia Alsbury MS0141 ANGRY Uptune M/D Marsha Zwicker MS0127 ANNIVERSARY SONG Ballad D Norma Andersen MS0116 ANOTHER OP'NIN', ANOTHER SHOW Uptune M Dot Calvin MS0117 ANYTHING GOES Uptune M George Avener MS10003 AS LONG AS I HAVE MUSIC Ballad M Marge Bailey MA0054 AT THE CODFISH BALL Uptune M Doris Twardosky MS0130 AT THE HOP Uptune E Sonny Steffan MA0069 AT THE MISSISSIPPI CABARET Uptune M Doris Twardosky MA0025 ATLANTA, G. A. Uptune D Ann Minihane MA0070 AULD LANG SYNE** Holiday E Charlene Yazurlo MS0143 AWAY IN A MANGER** Holiday E Joni Bescos MS0422 BABY FACE Uptune M Joni Bescos MS0434 BABY, WON'T YOU PLEASE COME HOME M Jo Lund MS0431 BALLIN' THE JACK Uptune M Mary K. -

Carl Dengler Scrapbooks

CARL DENGLER COLLECTION RUTH T. WATANABE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SIBLEY MUSIC LIBRARY EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Processed by Mary J. Counts, spring 2006 and Mathew T. Colbert, fall 2007; Finding aid revised by David Peter Coppen, summer 2021 Carl Dengler and his band, at a performance at The Barn (1950): Tony Cataldo (trumpet), Carl Dengler (drums), Fred Schubert (saxophone), Ray Shiner (clarinet), Ed Gordon (bass), Gene Small (piano). Photograph from the Carl Dengler Collection, Scrapbook 3 (1950-1959). Carl Dengler and His Band, at unidentified performance (ca. 1960s). Photograph from the Carl Dengler Collection, Box 34/15. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of Collection . 4 Description of Series . 8 INVENTORY SUB-GROUP I: MUSIC LIBRARY Series 1: Manuscript Music . 13 Series 2: Published Sheet Music . 74 Series 3: Original Songs by Carl Dengler . 134 SUB-GROUP II: PAPERS Series 4: Photographs . 139 Series 5: Scrapbooks . 158 Series 6: Correspondence . 160 Series 7: Programs . 161 Series 8: Press Material . 161 Series 9: Association with Alec Wilder . 162 Series 10: Books . 163 Series 11: Awards . 165 Series 12: Ephemera . 165 SUB-GROUP III: SOUND RECORDINGS Series 13: Commercial Recordings . 168 Series 14: Instantaneous Discs . 170 Series 15: Magnetic Reels . 170 Series 16: Audio-cassettes . 176 3 DESCRIPTION OF COLLECTION Shelf location: M4A 1,1-7 and 2,1-8 Extent: 45 linear feet Biographical Sketch (L) Carl Dengler, 1934; (Center) Carl Dengler with Sigmund Romberg, ca. 1942; (Right) Carl Dengler, undated (ca. 1960s). Photographs from the Carl Dengler Collection, Box 34/30, 34/39, 34/11. Musician Carl Dengler—dance band leader*, teacher, composer. -

Great Instrumental

I grew up during the heyday of pop instrumental music in the 1950s and the 1960s (there were 30 instrumental hits in the Top 40 in 1961), and I would listen to the radio faithfully for the 30 seconds before the hourly news when they would play instrumentals (however the first 45’s I bought were vocals: Bimbo by Jim Reeves in 1954, The Ballad of Davy Crockett with the flip side Farewell by Fess Parker in 1955, and Sixteen Tons by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1956). I also listened to my Dad’s 78s, and my favorite song of those was Raymond Scott’s Powerhouse from 1937 (which was often heard in Warner Bros. cartoons). and to records that my friends had, and that their parents had - artists such as: (This is not meant to be a complete or definitive list of the music of these artists, or a definitive list of instrumental artists – rather it is just a list of many of the instrumental songs I heard and loved when I was growing up - therefore this list just goes up to the early 1970s): Floyd Cramer (Last Date and On the Rebound and Let’s Go and Hot Pepper and Flip Flop & Bob and The First Hurt and Fancy Pants and Shrum and All Keyed Up and San Antonio Rose and [These Are] The Young Years and What’d I Say and Java and How High the Moon), The Ventures (Walk Don't Run and Walk Don’t Run ‘64 and Perfidia and Ram-Bunk-Shush and Diamond Head and The Cruel Sea and Hawaii Five-O and Oh Pretty Woman and Go and Pedal Pusher and Tall Cool One and Slaughter on Tenth Avenue), Booker T. -

“In the Mood”--Glenn Miller and His Orchestra (1939) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Dennis M

“In the Mood”--Glenn Miller and His Orchestra (1939) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Dennis M. Spragg (guest post)* “The Anthem of the Swing Era” On August 1, 1939, Glenn Miller and his Orchestra recorded the Joe Garland composition “In the Mood” for RCA Bluebird records. It became a top-selling record that would be permanently associated with Miller and which has become the easily recognized “anthem of the swing era.” “In the Mood” appears to have been inspired by several earlier works from which the tune was developed. Once composed, it remained a “work in progress” until recorded by Miller. The first indication of a composition with elements resembling what would become “In the Mood” was “Clarinet Getaway,” recorded by the Jimmy O’Bryant Washboard Wonders in 1925 for Paramount records. It is matrix number P-2148 and was issued as Paramount 12287. It was paired with a tune titled “Back Alley Rub.” The recording was made by a four-piece band with Arkansas native O’Bryant playing clarinet and accompanied by a piano, cornet and washboard player. Following O’Bryant, similar themes were evident in the Wingy Manone recording of “Tar Paper Stomp.” Manone’s recording is considered the genesis of “In the Mood” by most jazz historians. The recording is by Barbeque Joe and his Hot Dogs, the name under which Manone recorded at the time. Manone recorded “Tar Paper Stomp” on August 28, 1930, for the Champion label (which was acquired by Decca in 1935). Reissues credit the record to Wingy Manone and his Orchestra. -

Music Jazz Booklet

AQA Music A level Area of Study 5: Jazz NAME: TEACHER: 1 Contents Page Contents Page number What you will be studying 3 Jazz Timeline and background 4 Louis Armstrong 8 Duke Ellington 15 Charlie Parker 26 Miles Davis 33 Pat Metheny 37 Gwilym Simcock 40 Essay Questions 43 Vocabulary 44 2 You will be studying these named artists: Artists Pieces Louis Armstrong St. Louis Blues (1925, Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith) Muskrat Ramble (1926, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five) West End Blues (1928, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five) Stardust (1931, Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra) Duke Ellington The Mooche (1928, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Black and Tan (1929, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Ko-Ko (1940, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Come Sunday from Black, Brown and Beige (1943) Charlie Parker Ko-Ko (1945, Charlie Parker’s Reboppers) A Night in Tunisia (1946, Charlie Parker Septet) Bird of Paradise (1947, Charlie Parker Quintet) Bird Gets the Worm (1947, Charlie Parker All Stars) Miles Davis So What, from Kind of Blue (1959) Shhh, from In a Silent Way (1969) Pat Metheny (Cross the) Heartland, from American Garage (1979) Are you Going with Me?, from Offramp (1982) Gwilym Simcock Almost Moment, from Perception (2007) These are the Good Days, from Good Days at Schloss Elamau (2014) What you need to know: Context about the artist and the era(s) in which they were influential and the effect of audience, time and place on how the set works were created, developed and performed Typical musical features of that artist and their era – their purpose and why each era is different Musical analysis of the pieces listed for use in your exam How to analyse unfamiliar pieces from these genres Relevant musical vocabulary and terminology for the set works (see back of pack) 3 Jazz Timeline 1960’s 1980’s- current 1940’s- 1950’s 1920’s 1930’s 1940’s 1960’s- 1980’s 1870’s – 1910’s 1910-20’s St.