CONCEPT' of SELF in INDIAN Rhought by Father T. R. Jacob A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atman/Anatman in Buddhism

Åtman/Anåtman in Buddhism and Its Implication for the Wisdom Tradition by Nancy Reigle Does Christianity believe in reincarnation? Of course it does not. Yet, students of the Wisdom Tradition may seek to find evidence that early Christians did accept reincarnation. Similarly in Buddhism. Does Buddhism believe in the åtman, the permanent self? Certainly the Buddhist religion does not. Yet, there is evidence that the Buddha when teaching his basic doctrine of anåtman, no-self, only denied the abiding reality of the personal or empirical åtman, but not the universal or authentic åtman. The Wisdom Tradition known as Theosophy teaches the existence of “An Omnipresent, Eternal, Boundless, and Immu- table PRINCIPLE,” 1 often compared to the Hindu åtman, the universal “self,” while Buddhism with its doctrine of anåtman, “no-self,” is normally understood to deny any such universal principle. In regard to Buddhism, however, there have been several attempts to show that the Buddha did not deny the exist- ence of the authentic åtman, the self.2 Only one of these attempts seems to have been taken seriously by scholars3; namely, the work of Kamaleswar Bhattacharya. His book on this subject, written in French, L’Åtman-Brahman dans le Bouddhisme ancien, was published in Paris in 1973; and an English translation of this work, The Åtman-Brahman in Ancient Buddhism, was published in 2015.4 It is here that he set forth his arguments for the existence of the Upanißadic åtman in early Buddhism. This is the work that we will discuss. How must we understand -

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

9. Brahman, Separate from the Jagat

Chapter 9: Brahman, Separate from the Jagat Question 1: Why does a human being see only towards the external vishayas? Answer: Katha Upanishad states in 2.1.1 that Paramatma has carved out the indriyas only outwards and therefore human beings see only towards external vishayas. परािच खान यतणृ वयभूतमापरा पयत नातरामन .् Question 2: What is the meaning of Visheshana? What are the two types of Visheshanas of Brahman? Answer: That guna of an object which separates it from other objects of same jati (=category) is known as Visheshana. For example, the ‘blue color’ is guna of blue lotus. This blue color separates this blue lotus from all other lotuses (lotus is a jati). Therefore, blue color is a Visheshana. The hanging hide of a cow separates it from all four-legged animals. Thus, this hanging hide is a Visheshana of cow among the jati of four-legged animals. The two types of Visheshanas of Brahman which are mentioned in Shruti are as follows:- ● Bhava-roopa Visheshana (Those Visheshanas which have existence) ● Abhava-roopa Visheshana (Those Visheshanas which do not exist) Question 3: Describe the bhava-roopa Visheshanas of Brahman? Answer: Visheshana refers to that guna of object which separates it from all other objects of same jati. Now jati of human beings is same as that of Brahman. Here, by Brahman, Ishvara is meant who is the nimitta karan of jagat. Both human being as well as Brahman (=Ishvara) has jnana and hence both are of same jati. However, there is great difference between both of them and thus Brahman (=Ishvara) is separated due to the following bhava-roopa Visheshanas:- ● Human beings have limited power, but Brahman is omnipotent. -

ADVAITA 18 Diagrams Combined

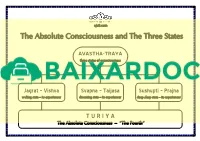

ajati.com The Absolute Consciousness and The Three States AVASTHA-TRAYA three states of consciousness Jagrat – Vishva Svapna – Taijasa Sushupti – Prajna waking state – its experiencer dreaming state – its experiencer deep sleep state – its experiencer TURIYA The Absolute Consciousness – “The Fourth“ ajati.com Bodies, Sheaths, States and Internal Instrument Sharira-Traya Pancha-Kosha Avastha-Traya Antahkarana Three Bodies Five Sheaths Three States Internal Instrument Sthula Sharira Annamaya Kosha Jagrat - Waking Ahamkara - Ego - Active (1) (1) (1) Buddhi - Intellect - Active Gross Body Food Sheath Vishva - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Active Chitta - Memory - Active Pranamaya Kosha (2) Vital Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Sukshma Sharira Manomaya Kosha Svapna - Dream Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (2) (3) (2) Subtle Body Mental Sheath Taijasa - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Inactive Chitta - Memory - Active Vijnanamaya Kosha (4) Intellect Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Karana Sharira Anandamaya Kosha Sushupti - Deep Sleep Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (3) (5) (3) Manas - Mind - Inactive Causal Body Bliss Sheath Prajna - Experiencer Chitta - Memory - Inactive ajati.com Description of Ignorance Ajnana – Characteristics Anadi Anirvachaniya Trigunatmaka Bhavarupa Jnanavirodhi Indefinable either as Made of three Experienced, Removed by Beginningless real (sat) or unreal (asat) tendencies (guna-s) hence present knowledge (jnana) Sattva Rajas Tamas Ajnana – Powers Avarana - Shakti Vikshepa - Shakti Veiling Power Projecting Power veils jiva 's real -

Philosophy of Mind: an Advaita Vedanta Perspective

Philosophy of Mind: An Advaita Vedanta Perspective SURYA KANT A MAHARANA Philosophy of mind and the philosophical issues arising in the allied domain of cognitive sciences constitute a fast developing territory in the world of philosophical enquiry. The origin of the philosophy of mind can be traced back to the Greek period. Anaxagoras (of Athens; perhaps in 500-428 BC) taught tha t all things come from the mixing of innumerable tiny particles of all kinds of substance, shaped by a separate, immaterial, creating principle, Nous ('Mind'). Nous is not explicitly called divine, but has the qualities of a creating god; Nous does not create matter, but rather creates the forms that matter assumes. However, in the Western philosophical tradition, one can hardly find a cleavage between mind a nd consciousness. On the contrary, it is quite fascinating to discover th at there is a hard and fast cleavage be tween miJU! and consciousness in the classical Indian philosophical tradition, especiall y in the tradition of Advaita Vedanta. In this direction, the paper is an attempt to discover the unique structure of mind and to distinguish it from consciousness in the light of the champion of Advaita Vedanta, Adi Salikaracarya. To begin wi th, in the Western tradition, the terms 'mind', 'self' and 'consciousness' are often used synonymously. The renowned philosopher, Rene Descartes, makes a sharp and radical division between mind and body. 1 The two are regarded as separate and independent substances and it is thought that the interaction between ~hem is i.mpossible c x~ept t~rough some inexplicable or mysterious mterv~nll on or connectiOn.' Tile facts of the connection between body and mmd are so compelhng that Descartes was obliged to assume the connection between the two through the pineal gland. -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

Neuroscience of the Yogic Theory of Mind and Consciousness

1 Neuroscience of the Yogic Theory of 2 Mind and Consciousness 3 Vaibhav Tripathi1* and Pallavi Bharadwaj2 *For correspondence: [email protected] (VT) 4 1Boston University; 2Massachusetts Institute of Technology † Present address: Department of 5 Psychological and Brain Sciences, Boston University, Boston, MA, ‡ USA 02215; Laboratory for 6 Abstract Yoga as a practice and philosophy of life has been followed for more than 4500 years Information and Decision Systems, 7 Massachusetts Institute of with known evidence of Yogic practices in the Indus Valley Civilization. A plethora of scholars have Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 8 contributed to the development of the field, but in last century the profound knowledge 9 remained inaccessible and incomprehensible to the general public. Last few decades have seen a 10 resurgence in the utility of Yoga and Meditation as a practice with growing scientific evidence 11 behind it. Significant scientific literature has been published, illustrating the benefits of Yogic 12 practices including asana, pranayama and dhyana on mental and physical well being. 13 Electrophysiological and recent functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies have 14 found explicit neural signatures for Yogic practices. In this article, we present a review of the 15 philosophy of Yoga, based on the dualistic Sankhya school, as applied to consciousness 16 summarized by Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras followed by discussion on the five vritti (modulations 17 of mind), practice of pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, different states of samadhi, and samapatti. We 18 introduce Yogic Theory of Mind and Consciousness (YTMC), a cohesive theory that can model 19 both external modulations and internal states of the mind. -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

Buddhist Psychology

CHAPTER 1 Buddhist Psychology Andrew Olendzki THEORY AND PRACTICE ince the subject of Buddhist psychology is largely an artificial construction, Smixing as it does a product of ancient India with a Western movement hardly a century and a half old, it might be helpful to say how these terms are being used here. If we were to take the term psychology literally as referring to “the study of the psyche,” and if “psyche” is understood in its earliest sense of “soul,” then it would seem strange indeed to unite this enterprise with a tradition that is per- haps best known for its challenge to the very notion of a soul. But most dictio- naries offer a parallel definition of psychology, “the science of mind and behavior,” and this is a subject to which Buddhist thought can make a significant contribution. It is, after all, a universal subject, and I think many of the methods employed by the introspective traditions of ancient India for the investigation of mind and behavior would qualify as scientific. So my intention in using the label Buddhist Psychology is to bring some of the insights, observations, and experi- ence from the Buddhist tradition to bear on the human body, mind, emotions, and behavior patterns as we tend to view them today. In doing so we are going to find a fair amount of convergence with modern psychology, but also some intriguing diversity. The Buddhist tradition itself, of course, is vast and has many layers to it. Al- though there are some doctrines that can be considered universal to all Buddhist schools,1 there are such significant shifts in the use of language and in back- ground assumptions that it is usually helpful to speak from one particular per- spective at a time.