Bach's Cantata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun Laßt Uns Gehn Und Treten 8.8

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun laßt uns gehn und treten 8.8. 8.8. Nun lasst uns Gott, dem Herren Paul Gerhardt, 1653 Nikolaus Selnecker, 1587 4 As mothers watch are keeping 9 To all who bow before Thee Tr. John Kelly, 1867, alt. Arr. Johann Crüger, alt. O’er children who are sleeping, And for Thy grace implore Thee, Their fear and grief assuaging, Oh, grant Thy benediction When angry storms are raging, And patience in affliction. 5 So God His own is shielding 10 With richest blessings crown us, And help to them is yielding. In all our ways, Lord, own us; When need and woe distress them, Give grace, who grace bestowest His loving arms caress them. To all, e’en to the lowest. 6 O Thou who dost not slumber, 11 Be Thou a Helper speedy Remove what would encumber To all the poor and needy, Our work, which prospers never To all forlorn a Father; Unless Thou bless it ever. Thine erring children gather. 7 Our song to Thee ascendeth, 12 Be with the sick and ailing, Whose mercy never endeth; Their Comforter unfailing; Our thanks to Thee we render, Dispelling grief and sadness, Who art our strong Defender. Oh, give them joy and gladness! 8 O God of mercy, hear us; 13 Above all else, Lord, send us Our Father, be Thou near us; Thy Spirit to attend us, Mid crosses and in sadness Within our hearts abiding, Be Thou our Fount of gladness. To heav’n our footsteps guiding. 14 All this Thy hand bestoweth, Thou Life, whence our life floweth. -

Biography Thomaskantor Gotthold Schwarz As of March 2018

Thomaskantor Gotthold Schwarz Gotthold Schwarz is the 17 th Thomaskantor after Johann Sebastian Bach. On 9 June 2016 he has been appointed as Thomaskantor and has been officially inaugurated on 20 August 2016. Born in Zwickau as a son of a cantor he gained his musical education at the “Hochschule für Kirchenmusik Dresden” (University for Church Music Dresden) and also at the “Hochschule für Musik und Theater „Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy“ Leipzig” (University of Music and Theatre „Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy“ Leipzig) after having been a member of Thomanerchor Leipzig for s short time in his childhood. He studied singing with Gerda Schriever, playing the organ with former St. Thomas Organist Hannes Kästner and Wolfgang Schetelich, as well as conducting with Max Pommer and Hans-Joachim Rotzsch. Furthermore he has worked with, amongst others, Hermann Christian Polster, Peter Schreier and Helmuth Rilling in masterclasses and academies. Gotthold Schwarz, who began to work as vocal trainer for the Thomanerchor Leipzig in 1979, stood in for the Thomaskantor for several times since the 1990's. On this position he led the motets, performances of cantatas and oratorios with the Thomanerchor Leipzig; moreover he was entrusted with other duties as an interim officiating cantor. Together with the world-famous boys’ choir he has been on numerous tours in Germany, Europe and overseas (Japan, China, USA, Canada), several together with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig. Furthermore Gotthold Schwarz is initiator and leader of “Concerto vocale”, “Saxon Baroque Orchestra”, “Leipziger Cantorey” and “Bach Consort Leipzig”. In recognition of his special merits the versatiled singer and conductor was awarded with the Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1 st class) on 4 October 2017. -

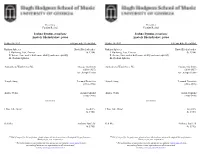

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

Introduction

Copyright © Thomas Braatz, 20071 Introduction This paper proposes to trace the origin and rather quick demise of the Andreas Stübel Theory, a theory which purportedly attempted to designate a librettist who supplied Johann Sebastian Bach with texts and worked with him when the latter composed the greater portion of the 2nd ‘chorale-cantata’ cycle in Leipzig from 1724 to early 1725. It was Hans- Joachim Schulze who first proposed this theory in 1998 after which it encountered a mixed reception with Christoph Wolff lending it some support in his Bach biography2 and in his notes for the Koopman Bach-Cantata recording series3, but with Martin Geck4 viewing it rather less enthusiastically as a theory that resembled a ball thrown onto the roulette wheel and having the same chance of winning a jackpot. 1 This document may be freely copied and distributed providing that distribution is made in full and the author’s copyright notice is retained. 2 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (Norton, 2000), (first published as a paperback in 2001), p. 278. 3 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Leipzig church cantatas: the chorale cantata cycle (II:1724-1725)’ in The Complete Cantatas volumes 10 and 11 as recorded by Ton Koopman and published by Erato Disques (Paris, France, 2001). 4 Martin Geck, Bach: Leben und Werk, (Hamburg, 2000), p. 400. 1 Andreas Stübel Andreas Stübel (also known as Stiefel = ‘boot’) was born as the son of an innkeeper in Dresden on December 15, 1653. In Dresden he first attended the Latin School located there. Then, in 1668, he attended the Prince’s School (“Fürstenschule”) in Meißen. -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Ctspubs Brochure Nov 2005

THE MUSIC OF CLAUDE T. SMITH CONCERT BAND WORKS ENJOY A CD RECORDING CTS = Claude T. Smith Publications WJ = Wingert-Jones HL = Hal Leonard TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER $1 OF THE MUSIC OF 7.95 each Acclamation..............................................................5 ..............Kalmus Intrada: Adoration and Praise ..................................4 ................CTS All 6 for Across the Wide Missouri (Concert Band) ................3..................WJ Introduction and Caccia............................................3 ................CTS $60 Affirmation and Credo ..............................................4 ................CTS Introduction and Fugato............................................3 ................CTS Claude T. Smith Allegheny Portrait ....................................................4 ................CTS Invocation and Jubiloso ............................................2 ..................HL Allegro and Intermezzo Overture ..............................3 ................CTS Island Fiesta ............................................................3 ................CTS America the Beautiful ..............................................2 ................CTS Joyance....................................................................5..................WJ CLAUDE T. SMITH: CLAUDE T. SMITH: American Folk Trilogy ..............................................3 ................CTS Jubilant Prelude ......................................................4 ..................HL A SYMPHONIC PORTRAIT -

Josquin Des Prez: Master of the Notes

James John Artistic Director P RESENTS Josquin des Prez: Master of the Notes Friday, March 4, 2016, 8 pm Sunday, March 6, 2016, 3pm St. Paul’s Episcopal Church St. Ignatius of Antioch 199 Carroll Street, Brooklyn 87th Street & West End Avenue, Manhattan THE PROGRAM CERDDORION Sopranos Altos Tenors Basses Gaude Virgo Mater Christi Anna Harmon Jamie Carrillo Ralph Bonheim Peter Cobb From “Missa de ‘Beata Virgine’” Erin Lanigan Judith Cobb Stephen Bonime James Crowell Kyrie Jennifer Oates Clare Detko Frank Kamai Jonathan Miller Gloria Jeanette Rodriguez Linnea Johnson Michael Klitsch Michael J. Plant Ellen Schorr Cathy Markoff Christopher Ryan Dean Rainey Praeter Rerum Seriem Myrna Nachman Richard Tucker Tom Reingold From “Missa ‘Pange Lingua’” Ron Scheff Credo Larry Sutter Intermission Ave Maria From “Missa ‘Hercules Dux Ferrarie’” BOARD OF DIRECTORS Sanctus President Ellen Schorr Treasurer Peter Cobb Secretary Jeanette Rodriguez Inviolata Directors Jamie Carrillo Dean Rainey From “Missa Sexti toni L’homme armé’” Michael Klitsch Tom Reingold Agnus Dei III Comment peut avoir joye The members of Cerddorion are grateful to James Kennerley and the Church of Saint Ignatius of Petite Camusette Antioch for providing rehearsal and performance space for this season. Jennifer Oates, soprano; Jamie Carillo, alto; Thanks to Vince Peterson and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church for providing a performance space Chris Ryan, Ralph Bonheim, tenors; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses for this season. Thanks to Cathy Markoff for her publicity efforts. Mille regretz Allégez moy Jennifer Oates, Jeanette Rodriguez, sopranos; Jamie Carillo, alto; PROGRAM CREDITS: Ralph Bonheim, tenor; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses Myrna Nachman wrote the program notes.