Namibia Since Geneva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Episcopalciiuriimen

EPISCOPALCIIURIIMEN soUru VAFR[CA Room 1005 * 853 Broadway, New York, N . Y. 10003 • Phone : (212) 477-0066 , —For A free Southern Afilcu ' May 1982 MISSIONS MOVEMENTS NAMIBIA 'The U .S. 'overnment has become an agent in South Africa's "holy crusade" against Communism . ' - The Rev Dr Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the Council of Churches in Namibia, THE NEW YORK TIMES, 25 April 1982. It was a . mission of frustration and a harsh learning experience . Four Namibian churchmen made a month-long visit to Western nations to express their feelings about the unending, agonizing occupation of their country by the South African regime and the fruitless talks on a Namibian settlement which the .Western Contact Group - the USA, Britain, France ,West Germany and Canada - has staged for five long years . Anglican Bishop James Kauluma, presi- dent of the Council of Churches in Namibia ; Bishop Kleopas Du neni of the Evangelical Luth- eran Ovambokavango Church ; Pastor Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the CCN ;, and the, assistant to Bishop D,mmeni, Pastor Absalom Hasheela, were accompanied by a representative of the South African Council of Churches and the general secretary of the All Africa Coun- cil of Oburches which sponsored the trip . They visited France, Sweden, Britain and Canada, end terminated their journey in the United States . It was here that the Namibian pilgrims encountered the steely disregard for Namibian aspirations by functionaries of a major power mapped up in its geopolitical stratagems. They met with Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester .Crocker, whose time is primarily devoted to pursuing the mirage of a Pretorian agreement to the United Nations settlement plan for Namibia . -

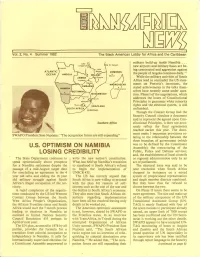

U.S. Optimism on Namibia Losing Credibility

Vol. 2, No. 4 Summer 1982 The Black American Lobby for Africa and the Caribbean military build-up inside Namibia ... new airports and military bases are be~ ing constructed and aggression against COMOROS the people of Angola continues daily.'' Mo~o~ While the military activities of South Africa tend to contradict the US state ments on Pretoria's intentions, the M(JADAGASfAR stated achievements in the talks them ananvo selves have recently come under ques tion. Phase I of the negotiations, which addresses the issues of Constitutional Principles to guarantee white minority rights and the electoral system, is still unfinished. Though the Contact Group had the Security Council circulate a document said to represent the agreed upon Con Southern A/rica stitutional Principles, it does not accu rately reflect the final agreements .._....... reached earlier this year. The docu ment omits 3 important provisions re SWAPO President Sam Nujoma: ''The occupation forces are still expanding'' lating to the relationship between the three branches of government (which was to be defined by the Constituent U.S. OPTIMISM ON NAMIBIA Assembly); the restructuring of the LOSING CREDIBILITY Public, Police and Defense services; and, the establishment of local councils The State Department continues to write the new nation's constitution. or regional administration only by an speak optimistically about prospects What has held up Namibia's transition act of parliament. for a Namibia settlement despite the to statehood is South Africa's refusal The electoral issue was said to be passage of a mid-August target date to begin the implementation of near resolution when South Africa for concluding an agreement in the 4 UNSCR435. -

The Cassinga Massacre of Namibian Exiles in 1978 and the Conflicts Between Survivors’ Memories and Testimonies

ENDURING SUFFERING: THE CASSINGA MASSACRE OF NAMIBIAN EXILES IN 1978 AND THE CONFLICTS BETWEEN SURVIVORS’ MEMORIES AND TESTIMONIES BY VILHO AMUKWAYA SHIGWEDHA A Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of the Western Cape December 2011 Supervisor: Professor Patricia Hayes ABSTRACT During the peak of apartheid, the South African Defence Force (SADF) killed close to a thousand Namibian exiles at Cassinga in southern Angola. This happened on May 4 1978. In recent years, Namibia commemorates this day, nationwide, in remembrance of those killed and disappeared following the Cassinga attack. During each Cassinga anniversary, survivors are modelled into „living testimonies‟ of the Cassinga massacre. Customarily, at every occasion marking this event, a survivor is delegated to unpack, on behalf of other survivors, „memories of Cassinga‟ so that the inexperienced audience understands what happened on that day. Besides survivors‟ testimonies, edited video footage showing, among others, wrecks in the camp, wounded victims laying in hospital beds, an open mass grave with dead bodies, SADF paratroopers purportedly marching in Cassinga is also screened for the audience to witness the agony of that day. Interestingly, the way such presentations are constructed draw challenging questions. For example, how can the visual and oral presentations of the Cassinga violence epitomize actual memories of the Cassinga massacre? How is it possible that such presentations can generate a sense of remembrance against forgetfulness of those who did not experience that traumatic event? When I interviewed a number of survivors (2007 - 2010), they saw no analogy between testimony (visual or oral) and memory. They argued that memory unlike testimony is personal (solid, inexplicable and indescribable). -

Politics in Southern Africa: State and Society in Transition

EXCERPTED FROM Politics in Southern Africa: State and Society in Transition Gretchen Bauer and Scott D. Taylor Copyright © 2005 ISBNs: 1-58826-332-0 hc 1-58826-308-8 pb 1800 30th Street, Ste. 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the Lynne Rienner Publishers website www.rienner.com i Contents Acknowledgments ix Map of Southern Africa xi 1 Introduction: Southern Africa as Region 1 Southern Africa as a Region 3 Theory and Southern Africa 8 Country Case Studies 11 Organization of the Book 15 2 Malawi: Institutionalizing Multipartyism 19 Historical Origins of the Malawian State 21 Society and Development: Regional and Ethnic Cleavages and the Politics of Pluralism 25 Organization of the State 30 Representation and Participation 34 Fundamentals of the Political Economy 40 Challenges for the Twenty-First Century 43 3 Zambia: Civil Society Resurgent 45 Historical Origins of the Zambian State 48 Society and Development: Zambia’s Ethnic and Racial Cleavages 51 Organization of the State 53 v vi Contents Representation and Participation 59 Fundamentals of the Political Economy 68 Challenges for the Twenty-First Century 75 4 Botswana: Dominant Party Democracy 81 Historical Origins of the Botswana State 83 Organization of the State 87 Representation and Participation 93 Fundamentals of the Political Economy 101 Challenges for the Twenty-First Century 104 5 Mozambique: Reconstruction and Democratization 109 Historical Origins of the Mozambican State 113 Society and Development: Enduring Cleavages -

Frontline States of Southern Africa: the Case for Closer Co-Operation', Atlantic Quarterly (1984), II, 67-87

Zambezia (1984/5), XII. THE FRONT-LINE STATES, SOUTH AFRICA AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN SECURITY: MILITARY PROSPECTS AND PERSPECTIVES* M. EVANS Department of History, University of Zimbabwe SINCE 1980 THE central strategic feature of Southern Africa has been the existence of two diametrically opposed political, economic and security groupings in the subcontinent. On one hand, there is South Africa and its Homeland satellite system which Pretoria has hoped, and continues to hope, will be the foundation stone for the much publicized, but as yet unfulfilled, Constellation of Southern African States (CONSAS) - first outlined in 1979 and subsequently reaffirmed by the South African Minister of Defence, General Magnus Malan, in November 1983.1 On the other hand, there is the diplomatic coalition of independent Southern African Front-line States consisting of Angola, Botswana, Mozambi- que, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. This grouping, originally containing the first five states mentioned, emerged in 1976 in order to crisis-manage the Rhodesia- Zimbabwe war, and it was considerably strengthened when the resolution of the conflict resulted in an independent Zimbabwe becoming the sixth Front-line State in 1980.2 Subsequently, the coalition of Front-line States was the driving force behind the creation of the Southern African Development Co-ordination Conference (SADCC) and was primarily responsible for blunting South Africa's CONSAS strategy in 1979-80. The momentous rolling back of Pretoria's CONSAS scheme can, in retrospect, be seen as the opening phase in an ongoing struggle between the Front-line States and South Africa for diplomatic supremacy in Southern Africa in the 1980s. Increasingly, this struggle has become ominously militarized for the Front Line; therefore, it is pertinent to begin this assessment by attempting to define the regional conflictuai framework which evolved from the initial confrontation of 1979-80 between the Front-line States and South Africa. -

NAM \ BIAN Ll BE RATION

NAM \ BIAN Ll BE RATION: 5EL~· D£/FRM!NATIO ~ LAW MD POLITICS ELIZA8ET~ S. LANDIS EPISCOPAL CHUR&liMEN for SOUTH Room 1005 • 853 Broadway, New York, N. Y. 10003 • Phone: (212) 477·0066 -For A Free S1111tbem Alritll- NOVEMBER 1982 NAMIBIAN LIBERATION Independence for Namibia is one of the forenost issues of today's world that cries for solution. The Namibian people have been subjected to bru tal foreign rule and their land exploited by co lonial powers for a century. Their thrust for freedom has intensified since 1966 when SWAPO launched its armed struggle against the illegal South African occupiers of its country. Their cause has been on the agendas of the League of Nations and the United Nations for m:>re than six decades . NCM, after five-and-a-half years of 'delicate negotiations 1 managed by five Western powers , Namibia is no nearer independence. Pretoria is m:>re repressively in oontrol of the Terri torY and uses it as a staging ground for its militarY encroaclunents into Angola and as a fulcrum for its attempt to reverse the tide of liberation in Southern Africa. Yet the talks conducted by the Western Contact Group are dragged on, with the United States gov ernment insisting that Angola denude itself of its CUban allies as a pre-condition for a 1 Namibian settlement" . There is widespread confusion on just where the matter of Namibia stands. This report is designed to penetrate the tangle. This clear, succinct and timely analysis of the Namibian issue by Elizabeth S. landis comes out of the author's yearn of work in the African field and her dedication to the cause of freedom in Southern Africa. -

Frican O Fere Ce Veo Me

WASHINGTON OFFICE ON AFRICA EDUCATIONAL FUN D 110 Maryland Avenue, NE. Washington, DC 20002. 202/546-7961 --~--cc: frican veo me o fere ce hat is DCC? The Southern African Development Coordination Con ference (SADCC) (pronounc~d "saddick") is an associ ation of nlne major y-r led a e of outhern Afrlca. Through reglonal cooperation SADCC work to ac celerate economic growt ,improve the living condi tions of the people of outhern Africa, and reduce the dependence of member ate on South Afrlc8. SADCC is primarily an economic grouping of states with a variety of ideologies, and which have contacts with countries from ail blocs. It seeks cooperation and support from the interna tional community as a whole: Who i SA CC? The Member States of SADCC are: Angola* Bot wana* Le otho Malawi Mozambique* .Swaziland • The forging of links between member states in order to regiona~ Tanzania*' create genuine and equitable integration; Zambia* • The mobilization of resources to promote the imple Zimbabwe* mentation of national, interstate and regional policies; The liberation movements of southern Africa recognized by • Concerted action to secure international cooperation the Organization of African Unity (the African National within the framework of SADCC's strategy of economic Congress, the Pan African Congress and the South West Iiberation. Africa People's Organization) are invited to SADCC Summit meeting's as obsérvers. At the inaugural meeting of SADCC, President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia said: What Are the Objective of SADCC? Let us now face the economic challenge. Let us form a powerful front against poverty and ail of its off • The reduction of economic dependence, particularly on shoots of hunger, ignorance, disease, crime and the Republic of South Africa; exploitation of man by man. -

Namibia and the Southern African Development Community Kaire M Mbuende*

Namibia and the Southern African Development Community Kaire M Mbuende* Introduction The relationship between Namibia and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) can be understood on the basis of the history and trajectories of the community on the one hand, and Namibia’s developmental objectives – of which its foreign policy is an instrument – on the other. This paper aims to shed light on SADC’s integration agenda and Namibia’s participation in it. At the same time, the discussion intends to contribute to an understanding of Namibia’s foreign policy as exemplified by its participation in the SADC regional integration scheme. SADC is a product of the unique historical circumstances of southern Africa. The countries1 of the region cemented their cooperation in pursuing the political agenda of liberating themselves from the yoke of colonialism through the Frontline States (FLS). In 1980, an economic dimension was added to the political cooperation through a different entity, the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC),2 with broader membership than the FLS. The agenda for economic cooperation and development aimed at complementing the political strategy. SADCC’s primary objective was to reduce the region’s economic dependency on apartheid South Africa, and to enable them to effectively support the struggle for the independence of Namibia and the democratisation of South Africa. With the independence of Namibia and the imminent demise of apartheid in South Africa, SADCC was reconstituted as SADC3 in 1992. The new body aimed at attaining a higher level of cooperation that –4 … would enable the countries of the region to address problems of national development, and cope with the challenges posed by a changing, and increasingly complex, regional and global environment more effectively. -

Promoting Democracy and Good Governance

State Formation in Namibia: Promoting Democracy and Good Governance By Hage Gottfried Geingob Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Politics and International Studies March 2004 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. encourage good governance, to promote a culture of human rights, and to build state institutions to support these policies have also been examined with a view to determining the nature of the state that evolved in Namibia. Finally, the study carries out a democratic audit of Namibia using Swedish normative tools. 1 Acknowledgements The last few years have been tumultuous but exciting. Now, the academic atmosphere that provided a valuable anchor, too, must be hauled up for journeys beyond. The end of this most enjoyable academic challenge has arrived, but I cannot look back without a sense of loss - loss of continuous joys of discovery and academic enrichment. I would like to thank my supervisor, Lionel Cliffe, for his incredible support. In addition to going through many drafts and making valuable suggestions, Lionel helped me endure this long journey with his sustained encouragement. I also thank Ray Bush for going through many drafts and making valuable comments. He has an uncanny ability to visualize the final outcome of research effort. -

Southern Africa Under Threat*

SOUTHERN AFRICA UNDER THREAT* The nine IIIAjority-ruled states of southern Africa--1\ngola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zi.JIIbabwe--entered 1982 facing two threats: a threat of economic crisis, and a threat of destabilisation fraa the Republic of South Africa. Both problema have roots in the his torical develop~~ent of a reqional econaay dominated by SOUth Africa. The countries to its north rely on trade for their prosperity, and are ill- prepared for the shocks of world reces sion. They are to varying degrees vulnerable to SOUth Africa' s recent escalation of economic pressure and military attack. The first reaction of the IIIAjority-ruled states has been to seek a united position, through the foriiiAtion of the Southern African Development co-ordination COnference (SADCC) to co ordinate efforts for economic development and to reduce economic dependence on South Africa. The reaction of the West has been to offer support to SADCC, but at the same time to adopt a policy of conciliation towards South Africa. This conciliation has not restrained South Africa and appears to have encouraged even more aggressive actions against its neighbours. Firm pressure is needed if the majority-ruled states are to prosper. The alter native is poverty, disorder, and the opportunity for foreign intervention. The Individual States The nine countries have a combined population of almost sixty million people. They vary in population from swaziland's half-million people to eighteen million in Tanzania, and in area from Lesotho--about the size of Wales--to 1\ngola, over twice the size of France. -

The Saga of South African Pows in Angola, 1975-82

102 THE SAGA OF SOUTH AFRICAN POWS IN ANGOLA, 1975–82 Gary Baines History Department, Rhodes University Abstract This article narrates the story of nine soldiers captured during and shortly after Operation Savannah, the codename for the South African Defence Force invasion of Angola in 1975–6. Eight of these soldiers were captured in Angola in three separate incidents by Angolan and/or Cuban forces, whereas the last was abducted from northern Namibia by SWAPO (the South West Africa Peoples’ Organisation). The article then provides a chronological account of the sequels to this story that interweaves a number of threads: first, the account relates the South African government’s attempts to suppress press coverage of these stories for fear of the political ‘fall-out’ that the matter might cause amongst the white electorate and in case it jeopardised secret negotiations to secure the release of the prisoners; and second, it uncovers the role played by intermediaries, especially the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), in the sensitive and fraught negotiation process. It will be shown that the South African authorities adopted divergent approaches when dealing with SWAPO and the Angolans/Cubans to secure the release of prisoners of war (POWs). This is because the South African authorities regarded the former as involved in an internal insurrection whereas the latter were members of the military forces of sovereign states. Accordingly, they paid lip service to the Geneva Conventions in the case of Angolan and Cuban POWs but treated captured SWAPO cadres as ‘terrorists’ or ‘criminals’. Introduction Military and diplomatic historians have paid scant attention to the stories of South African Defence Force (SADF) soldiers captured during the war waged in Namibia/Angola.1 Those captured during Operation Savannah (1975–6) warrant a passing mention in a few texts,2 and are Scientia Militaria, South African alluded to in a recently produced documentary Journal of Military Studies, Vol video series.3 Still, the details of their 29 40, Nr 2, 2012, pp. -

America Needs a New South Africa Policy

AMERICA NEEDS A NEW SOUTH AFRICA POLICY JESSE L. JACKSON For many years now, while serving in the trenches of the Civil Rights Movement, and through the days of my involvement in the new movements of electoral politics, public policy, and economic development, I have carried with me an abiding concern with the future of Africa and of South Africa in particular. In these various endeavors, I have been keenly aware of the fact that the national goals of most groups in America have seldom been realized within a domestic context alone. It was the distinguished scholar, Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, who long ago said: "One ever feels his two-ness - an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder." In the continuing attempt to reconcile the heritage of Africa with that of America, generations of African and African-American leaders such as Paul Robeson, Roy Wilkins, Kwame Nkrumah, Martin Luther King, Jr., Julius Nyerere, and others have asserted the right and the obligation to become involved in the shaping of policy in their respective countries toward this end. These leaders allowed the blood and heritage of two continents to enable them to reconcile separate but related strivings and to help bridge the gap to make way for the lasting converging of interests of America and Africa. I stand firmly in the tradition of this legacy, as I discuss with you an African-American view of U.S. foreign policy toward the region of Southern Africa.