South Africa and Its Sadcc Neighbours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Reform from Post-Apartheid South Africa Catherine M

Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review Volume 20 | Issue 4 Article 4 8-1-1993 Land Reform from Post-Apartheid South Africa Catherine M. Coles Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ealr Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation Catherine M. Coles, Land Reform from Post-Apartheid South Africa, 20 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 699 (1993), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ealr/vol20/iss4/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAND REFORM FOR POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Catherine M. Coles* I. INTRODUCTION...................................................... 700 II. LAND SYSTEMS IN COLLISION: PRECOLONIAL AND COLONIAL LAND SYSTEMS IN SOUTH AFRICA. 703 A. An Overview of Precolonial Land Systems. 703 B. Changing Rights to Landfor Indigenous South African Peoples Under European Rule. 706 III. THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF RACIAL INEQUALITY AND APART- HEID THROUGH A LAND PROGRAM. 711 A. Legislative Development of the Apartheid Land Program. 712 B. The Apartheid System of Racial Zoning in Practice: Limiting the Land Rights of Black South Africans. 716 1. Homelands and National States: Limiting Black Access to Land by Restricting Citizenship. 716 2. Restricting Black Land Rights in Rural Areas Outside the Homelands through State Control. 720 3. Restricting Black Access to Urban Land..................... 721 IV. DISMANTLING APARTHEID: THE NATIONAL PARTY'S PLAN FOR LAND REFORM............................................................ -

Naveed Bork Memorial Tournament: Tippecanoe and Tejas

Naveed Bork Memorial Tournament: Tippecanoe and Tejas Too By Will Alston, with contributions from Itamar Naveh-Benjamin and Benji Nguyen, but not Joey Goldman Packet 3 1. A sculpture from this modern-day country found at a site called Alcudia is often interpreted as a bust of the goddess Tanit. Ephorus of Cyme described a magnificent harbor city found in this modern- day country called Tartessos. During the Iron Age, this modern-day country contained the southernmost expansion of the Halstatt culture. Models of the gladius made from the 3rd century BC onward were copied from designs from this country which, with Ireland, contained the most speakers of (*) Q-Celtic languages. The Roman-owned portions of this modern-day country were divided into portions named “Citerior” and “Ulterior” until a series of conquests that included the Cantabrian and Numantine Wars. Ancient settlements in this modern-day country include Saguntum and Carthago Nova. For 10 points, name this modern-day country where most Celtiberians lived. ANSWER: (Kingdom of) Spain [or Reino de Espana] 2. Unlike the painting it is based on, this painting places a single pearl earring on the only visible ear of its subject. A book about the “women” of the artist of this painting by Rona Goffen argues that a woman in it is masturbating. The presence of a single fallen rose in this painting is often interpreted as a sign of “plucked” virginity. Most critics instead theorize that, based on the cassoni in the right background, this painting may have been intended to instruct Giulia Varano and is thus an allegory of (*) marital obligations. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

SADF Military Operations

SADF Military Operations 1975 -1989 Contents 1 List of operations of the South African Border War 1 2 Operation Savannah (Angola) 3 2.1 Background .............................................. 3 2.2 Military intervention .......................................... 4 2.2.1 Support for UNITA and FNLA ................................ 5 2.2.2 Ruacana-Calueque occupation ................................ 5 2.2.3 Task Force Zulu ........................................ 5 2.2.4 Cuban intervention ...................................... 6 2.2.5 South African reinforcements ................................. 6 2.2.6 End of South African advance ................................ 6 2.3 Major battles and incidents ...................................... 6 2.3.1 Battle of Quifangondo .................................... 7 2.3.2 Battle of Ebo ......................................... 7 2.3.3 “Bridge 14” .......................................... 7 2.3.4 Battle of Luso ......................................... 7 2.3.5 Battles involving Battlegroup Zulu in the west ........................ 8 2.3.6 Ambrizete incident ...................................... 8 2.4 Aftermath ............................................... 8 2.5 South African order of battle ..................................... 9 2.6 Association .............................................. 9 2.7 Further reading ............................................ 9 2.8 References ............................................... 9 3 Operation Bruilof 13 3.1 Background ............................................. -

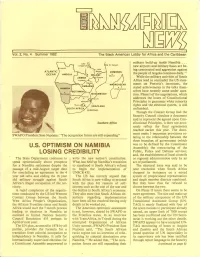

U.S. Optimism on Namibia Losing Credibility

Vol. 2, No. 4 Summer 1982 The Black American Lobby for Africa and the Caribbean military build-up inside Namibia ... new airports and military bases are be~ ing constructed and aggression against COMOROS the people of Angola continues daily.'' Mo~o~ While the military activities of South Africa tend to contradict the US state ments on Pretoria's intentions, the M(JADAGASfAR stated achievements in the talks them ananvo selves have recently come under ques tion. Phase I of the negotiations, which addresses the issues of Constitutional Principles to guarantee white minority rights and the electoral system, is still unfinished. Though the Contact Group had the Security Council circulate a document said to represent the agreed upon Con Southern A/rica stitutional Principles, it does not accu rately reflect the final agreements .._....... reached earlier this year. The docu ment omits 3 important provisions re SWAPO President Sam Nujoma: ''The occupation forces are still expanding'' lating to the relationship between the three branches of government (which was to be defined by the Constituent U.S. OPTIMISM ON NAMIBIA Assembly); the restructuring of the LOSING CREDIBILITY Public, Police and Defense services; and, the establishment of local councils The State Department continues to write the new nation's constitution. or regional administration only by an speak optimistically about prospects What has held up Namibia's transition act of parliament. for a Namibia settlement despite the to statehood is South Africa's refusal The electoral issue was said to be passage of a mid-August target date to begin the implementation of near resolution when South Africa for concluding an agreement in the 4 UNSCR435. -

Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: a Mixed Methods Approach

CRITICAL GEOPOLITICS OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT IN NAMIBIA: A MIXED METHODS APPROACH by MEREDITH JOY DEBOOM B.A., University of Iowa, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Geography 2013 This thesis entitled: Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach written by Meredith Joy DeBoom has been approved for the Department of Geography John O’Loughlin, Chair Joe Bryan, Committee Member Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Abstract DeBoom, Meredith Joy (M.A., Geography) Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach Thesis directed by Professor John O’Loughlin In May 2011, Namibia’s Minister of Mines and Energy issued a controversial new policy requiring that all future extraction licenses for “strategic” minerals be issued only to state-owned companies. The public debate over this policy reflects rising concerns in southern Africa over who should benefit from globally-significant resources. The goal of this thesis is to apply a critical geopolitics approach to create space for the consideration of Namibian perspectives on this topic, rather than relying on Western geopolitical and political discourses. Using a mixed methods approach, I analyze Namibians’ opinions on foreign involvement, particularly involvement in natural resource extraction, from three sources: China, South Africa, and the United States. -

Namibia Since Geneva

NAMIBIA SINCE GENEVA Andr6 du Pisani OCCASIONAL PAPER GELEEIUTHEIDSPUBUKASIE >-'''' •%?'"' DIE SUID-AFRIKAANSE INSTITUUT VAN INTERNASIONAIE AANGEIEENTHEDE THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Mr. Andre du Pisani is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at the University of South Africa. He is an acknowledged authority on SWA/Namibia, with numerous publications to his credit. It should be noted that any opinions expressed in this article are the responsibility of the author and not of the Institute. NAMIBIA SINCE GENEVA Andre du Pisani Contents Introduction Page 1 Premises of the West f. 1 Geneva: Backfrop and Contextual Features ,,.... 2 The Reagan Initiative - Outline of a position ........... 6 Rome - a New Equation Emerges T... 7 May - Pik Botha visits Washington ,.. tT,. f 7 South Africa's Bedrock Bargaining Position on Namibia ... 8 Clark Visit 8 Unresolved issues and preconditions t.. 8 Nairobi - OAU Meeting , 9 Mudge and Kalangula.Visit the US 9 Ottawa Summit '. , 10 Crocker meets SWAPO t 10 The Contact Group meets in Paris , , 10 Operation Protea T T 12 Constructive Engagement. - Further Clarifications 13 Confidence-building - The Crocker Bush Safari , 15 Prospects ,, 16 ISBN: 0 - 909239 - 95 - 9 The South African Institute of International Affairs Jan Smuts House P.O. Box 31596 BRAAMFONTEIN 2017 South Africa November 1981 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to reflect on diplomatic efforts by the Western powers to reach a negotiated settlement of the Namibian saga. Understandably one can only reflect on the major features of what has become a lengthy diplomatic soap opera with many actors on the stage. -

Zimbabwe-South Africa Interstate Relations, 1980-1999

Zimbabwe-South Africa Interstate Relations, 1980-1999 Lotti Nkomo THIS THESIS HAS BEEN SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FOR THE CENTRE FOR AFRICA STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF THE FREE STATE DECEMBER 2018 SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR NEIL ROOS CO-SUPERVISORS: DR DAVID PATRICK AND DR CLEMENT MASAKURE Declaration I declare that this dissertation is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me at another university or institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Signed………………………............. Date……………………………………… Lotti Nkomo Bloemfontein TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................. I Opsomming .......................................................................................................................... II Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. III Glossary ............................................................................................................................... VI Map Showing Geographical Locations of Zimbabwe and South Africa................................ IX Chapter One Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction and Background ............................................................................................... -

Politics in Southern Africa: State and Society in Transition

EXCERPTED FROM Politics in Southern Africa: State and Society in Transition Gretchen Bauer and Scott D. Taylor Copyright © 2005 ISBNs: 1-58826-332-0 hc 1-58826-308-8 pb 1800 30th Street, Ste. 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the Lynne Rienner Publishers website www.rienner.com i Contents Acknowledgments ix Map of Southern Africa xi 1 Introduction: Southern Africa as Region 1 Southern Africa as a Region 3 Theory and Southern Africa 8 Country Case Studies 11 Organization of the Book 15 2 Malawi: Institutionalizing Multipartyism 19 Historical Origins of the Malawian State 21 Society and Development: Regional and Ethnic Cleavages and the Politics of Pluralism 25 Organization of the State 30 Representation and Participation 34 Fundamentals of the Political Economy 40 Challenges for the Twenty-First Century 43 3 Zambia: Civil Society Resurgent 45 Historical Origins of the Zambian State 48 Society and Development: Zambia’s Ethnic and Racial Cleavages 51 Organization of the State 53 v vi Contents Representation and Participation 59 Fundamentals of the Political Economy 68 Challenges for the Twenty-First Century 75 4 Botswana: Dominant Party Democracy 81 Historical Origins of the Botswana State 83 Organization of the State 87 Representation and Participation 93 Fundamentals of the Political Economy 101 Challenges for the Twenty-First Century 104 5 Mozambique: Reconstruction and Democratization 109 Historical Origins of the Mozambican State 113 Society and Development: Enduring Cleavages -

Frontline States of Southern Africa: the Case for Closer Co-Operation', Atlantic Quarterly (1984), II, 67-87

Zambezia (1984/5), XII. THE FRONT-LINE STATES, SOUTH AFRICA AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN SECURITY: MILITARY PROSPECTS AND PERSPECTIVES* M. EVANS Department of History, University of Zimbabwe SINCE 1980 THE central strategic feature of Southern Africa has been the existence of two diametrically opposed political, economic and security groupings in the subcontinent. On one hand, there is South Africa and its Homeland satellite system which Pretoria has hoped, and continues to hope, will be the foundation stone for the much publicized, but as yet unfulfilled, Constellation of Southern African States (CONSAS) - first outlined in 1979 and subsequently reaffirmed by the South African Minister of Defence, General Magnus Malan, in November 1983.1 On the other hand, there is the diplomatic coalition of independent Southern African Front-line States consisting of Angola, Botswana, Mozambi- que, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. This grouping, originally containing the first five states mentioned, emerged in 1976 in order to crisis-manage the Rhodesia- Zimbabwe war, and it was considerably strengthened when the resolution of the conflict resulted in an independent Zimbabwe becoming the sixth Front-line State in 1980.2 Subsequently, the coalition of Front-line States was the driving force behind the creation of the Southern African Development Co-ordination Conference (SADCC) and was primarily responsible for blunting South Africa's CONSAS strategy in 1979-80. The momentous rolling back of Pretoria's CONSAS scheme can, in retrospect, be seen as the opening phase in an ongoing struggle between the Front-line States and South Africa for diplomatic supremacy in Southern Africa in the 1980s. Increasingly, this struggle has become ominously militarized for the Front Line; therefore, it is pertinent to begin this assessment by attempting to define the regional conflictuai framework which evolved from the initial confrontation of 1979-80 between the Front-line States and South Africa. -

Frican O Fere Ce Veo Me

WASHINGTON OFFICE ON AFRICA EDUCATIONAL FUN D 110 Maryland Avenue, NE. Washington, DC 20002. 202/546-7961 --~--cc: frican veo me o fere ce hat is DCC? The Southern African Development Coordination Con ference (SADCC) (pronounc~d "saddick") is an associ ation of nlne major y-r led a e of outhern Afrlca. Through reglonal cooperation SADCC work to ac celerate economic growt ,improve the living condi tions of the people of outhern Africa, and reduce the dependence of member ate on South Afrlc8. SADCC is primarily an economic grouping of states with a variety of ideologies, and which have contacts with countries from ail blocs. It seeks cooperation and support from the interna tional community as a whole: Who i SA CC? The Member States of SADCC are: Angola* Bot wana* Le otho Malawi Mozambique* .Swaziland • The forging of links between member states in order to regiona~ Tanzania*' create genuine and equitable integration; Zambia* • The mobilization of resources to promote the imple Zimbabwe* mentation of national, interstate and regional policies; The liberation movements of southern Africa recognized by • Concerted action to secure international cooperation the Organization of African Unity (the African National within the framework of SADCC's strategy of economic Congress, the Pan African Congress and the South West Iiberation. Africa People's Organization) are invited to SADCC Summit meeting's as obsérvers. At the inaugural meeting of SADCC, President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia said: What Are the Objective of SADCC? Let us now face the economic challenge. Let us form a powerful front against poverty and ail of its off • The reduction of economic dependence, particularly on shoots of hunger, ignorance, disease, crime and the Republic of South Africa; exploitation of man by man. -

Introduction 1. Among Many Examples Are: Pérez Jr., Cuba in the American Imagination, Also His on Becoming Cuban: Identity

Notes Introduction 1. Among many examples are: Pérez Jr., Cuba in the American Imagination, also his On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality and Culture, and Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy; Schoultz, That Infernal Little Cuban Republic; Morley, McGillion, and Kirk, eds., Cuba, the United States, and the Post–Cold War World; Morley, Imperial State and Revolution: The United States and Cuba, 1952–1986; Pérez-Stable, The United States and Cuba: Intimate Enemies; Franklin, Cuba and the United States; and Morales Domínguez, and Prevost, United States–Cuban Relations. 2. Ó Tuathail, “Thinking Critically about Geopolitics,” 1. 3. This notion corresponds with philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s theory that human actions, just like works of literature, “display a sense as well as a reference.” Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences, 16. In other words, the coexistence of internal and external systems of logic facili- tates both interpretation and explanation. 4. Ibid. 5. Throughout this work, the term africanía defines both an essential quality of Africanness as well as the accumulation of cultural reposi- tories (linguistic, religious, artistic, and so on) in which the African dimension resides. 6. On the other hand, several shorter analyses were published in the form of essays and journal articles. A few worth mentioning are: Casal, “Race Relations in Contemporary Cuba;” Taylor, “Revolution, Race and Some Aspects of Foreign Relations;” and the oft-cited contribu- tion from David Booth, “Cuba, Color and Revolution.” 7. Butterworth, The People of Buena Ventura, xxi–xxii. 8. Marti, Nuestra America, 38. 9. Martí, “Mi Raza,” 299. 10. Ibid., 298. 11. Guillén, “Sóngoro cosongo,” 114.