Syntactic Variation and Parametric Theory C.-T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Syntactic and Semantic Relationship in Synthetic Languages

This is the published version of the bachelor thesis: Navarro Caparrós, Raquel; van Wijk Adan, Malou, dir. The Syntactic and Semantic Relationship in Synthetic Languagues : Linear Modification in Latin and Old English. 2016. 41 pag. (838 Grau en Estudis d’Anglès i de Clàssiques) This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/164293 under the terms of the license The Syntactic and Semantic Relationship in Synthetic Languages: Linear Modification in Latin and Old English TFG – Grau d’Estudis d’Anglès i Clàssiques Supervisor: Malou van Wijk Adan Raquel Navarro Caparrós June 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Ms. Malou van Wijk Adan for her assistance and patience during the period of my research. This project would not have been possible without her guidance and valuable comments throughout. I would also like to thank all my teachers of Classical Studies and English Studies for sharing their knowledge with me throughout these four years. Finally, I wish to acknowledge my mum and my sister Ruth whose invaluable support helped me to overcome any obstacle, especially in the last two years. Without them, I am sure that I would have never been able to get where I am now. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................... ii List of Tables .................................................................................................................. iii Abstract .......................................................................................................................... -

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

Antisymmetry Kayne, Richard (1995)

CAS LX 523 Syntax II (1) A Spring 2001 March 13, 2001 qp Paul Hagstrom Week 7: Antisymmetry BE 33 Kayne, Richard (1995). The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. CDFG 1111 Koopman, Hilda (2000). The spec-head configuration. In Koopman, H., The syntax of cdef specifiers and heads. London: Routledge. (2) A node α ASYMMETRICALLY C-COMMANDS β if α c-commands β and β does not The basic proposals: c-command α. X-bar structures (universally) have a strict order: Spec-head-complement. There is no distinction between adjuncts and specifiers. • B asymmetrically c-commands F and G. There can be only one specifier. • E asymmetrically c-commands C and D. • No other non-terminal nodes asymmetrically c-command any others. But wait!—What about SOV languages? What about multiple adjunction? Answer: We’ve been analyzing these things wrong. (3) d(X) is the image of a non-terminal node X. Now, we have lots of work to do, because lots of previous analyses relied on d(X) is the set of terminal nodes dominated by node X. the availability of “head-final” structures, or multiple adjunction. • d(C) is {c}. Why make our lives so difficult? Wasn’t our old system good enough? • d(B) is {c, d}. Actually, no. • d(F) is {e}. A number of things had to be stipulated in X-bar theory (which we will review); • d(E) is {e, f}. they can all be made to follow from one general principle. • d(A) is {c, d, e, f}. The availability of a head-parameter actually fails to predict the kinds of languages that actually exist. -

Grammatical Analyticity Versus Syntheticity in Varieties of English

Language Variation and Change, 00 (2009), 1–35. © Cambridge University Press, 2009 0954-3945/09 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394509990123 1 2 3 4 Typological parameters of intralingual variability: 5 Grammatical analyticity versus syntheticity in varieties 6 7 of English 8 B ENEDIKT S ZMRECSANYI 9 Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies 10 11 12 ABSTRACT 13 Drawing on terminology, concepts, and ideas developed in quantitative morphological 14 typology, the present study takes an exclusive interest in the coding of grammatical 15 information. It offers a sweeping overview of intralingual variability in terms of 16 overt grammatical analyticity (the text frequency of free grammatical markers), 17 grammatical syntheticity (the text frequency of bound grammatical markers), and 18 grammaticity (the text frequency of grammatical markers, bound or free) in English. 19 The variational dimensions investigated include geography, text types, and real time. 20 Empirically, the study taps into a number of publicly accessible text corpora that 21 comprise a large number of different varieties of English. Results are interpreted in 22 terms of how speakers and writers seek to achieve communicative goals while 23 minimizing different types of complexity. 24 25 This study surveys language-internal variability and short-term diachronic change, 26 along dimensions that are familiar from the cross-linguistic typology of languages. 27 The terms analytic and synthetic have a long and venerable tradition in linguistics, 28 going back to the 19th century and August Wilhelm von Schlegel, who is usually 29 credited for coining the opposition (Schlegel, 1818). This is, alas, not the place to 30 even attempt to review the rich history of thought in this area (but see Schwegler, “ 31 1990:chapter 1 for an excellent overview). -

Antisymmetry and the Lefthand in Morphology*

CatWPL 7 071-087 13/6/00 12:26 Página 71 CatWPL 7, 1999 71-87 Antisymmetry And The Lefthand In Morphology* Frank Drijkoningen Utrecht Institute of Linguistics-OTS. Department of Foreign Languages Kromme Nieuwegracht 29. 3512 HD Utrecht. The Netherlands [email protected] Received: December 13th 1998 Accepted: March 17th 1999 Abstract As Kayne (1994) has shown, the theory of antisymmetry of syntax also provides an explanation of a structural property of morphological complexes, the Righthand Head Rule. In this paper we show that an antisymmetry approach to the Righthand Head Rule eventually is to be preferred on empirical grounds, because it describes and explains the properties of a set of hitherto puzz- ling morphological processes —known as discontinuous affixation, circumfixation or parasyn- thesis. In considering these and a number of more standard morphological structures, we argue that one difference bearing on the proper balance between morphology and syntax should be re-ins- talled (re- with respect to Kayne), a difference between the antisymmetry of the syntax of mor- phology and the antisymmetry of the syntax of syntax proper. Key words: antisymmetry, Righthand Head Rule, circumfixation, parasynthesis, prefixation, category-changing prefixation, discontinuities in morphology. Resum. L’antisimetria i el costat esquerre en morfologia Com Kayne (1994) mostra, la teoria de l’antisimetria en la sintaxi també ens dóna una explicació d’una propietat estructural de complexos morfològics, la Regla del Nucli a la Dreta. En aquest article mostrem que un tractament antisimètric de la Regla del Nucli a la Dreta es prefereix even- tualment en dominis empírics, perquè descriu i explica les propietats d’una sèrie de processos fins ara morfològics —coneguts com afixació discontínua, circumfixació o parasíntesi. -

Head Words and Phrases Heads and Their Dependents

Head Words and Phrases Tallerman: Chapter 4 Ling 222 - Chapter 4 1 Heads and their Dependents • Properties of heads – Head bears most important semantic information of the phrase. – Word class of head determines word class of entire phrase. • [NP very bright [N sunflowers] ] [VP [V overflowed] quite quickly] [AP very [A bright]] [AdvP quite [Adv quickly]] [PP [P inside] the house] Ling 222 - Chapter 4 2 1 – Head has same distribution as the entire phrase. • Go inside the house. Go inside. • Kim likes very bright sunflowers. Kim likes sunflowers. – Heads normally can’t be omitted • *Go the house. • *Kim likes very bright. Ling 222 - Chapter 4 3 – Heads select dependent phrases of a particular word class. • The soldiers released the hostages. • *The soldiers released. • He went into the house. *He went into. • bright sunflowers *brightly sunflowers • Kambera – Lalu mbana-na na lodu too hot-3SG the sun ‘The sun is hot.’ – *Lalu uma too house Ling 222 - Chapter 4 4 2 – Heads often require dependents to agree with grammatical features of head. • French – un livre vert a:MASC book green:MASC ‘a green book.’ – une pomme verte a:FEM apple green:FEM ‘a green apple’ – Heads may require dependent NPs to occur in a particular grammatical case. • Japanese – Kodomo-ga hon-o yon-da child-NOM book-ACC read-PAST ‘The child read the book.’ Ling 222 - Chapter 4 5 • More about dependents – Adjuncts and complements • Adjuncts are always optional; complements are frequently obligatory • Complements are selected by the head and therefore bear a close relationship with it; adjuncts add extra information. -

Modeling Infant Segmentation of Two Morphologically Diverse Languages

Modeling infant segmentation of two morphologically diverse languages Georgia Rengina Loukatou1 Sabine Stoll 2 Damian Blasi2 Alejandrina Cristia1 (1) LSCP, Département d’études cognitives, ENS, EHESS, CNRS, PSL Research University, Paris, France (2) University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland [email protected] RÉSUMÉ Les nourrissons doivent trouver des limites de mots dans le flux continu de la parole. De nombreuses études computationnelles étudient de tels mécanismes. Cependant, la majorité d’entre elles se sont concentrées sur l’anglais, une langue morphologiquement simple et qui rend la tâche de segmen- tation aisée. Les langues polysynthétiques - pour lesquelles chaque mot est composé de plusieurs morphèmes - peuvent présenter des difficultés supplémentaires lors de la segmentation. De plus, le mot est considéré comme la cible de la segmentation, mais il est possible que les nourrissons segmentent des morphèmes et non pas des mots. Notre étude se concentre sur deux langues ayant des structures morphologiques différentes, le chintang et le japonais. Trois algorithmes de segmentation conceptuellement variés sont évalués sur des représentations de mots et de morphèmes. L’évaluation de ces algorithmes nous mène à tirer plusieurs conclusions. Le modèle lexical est le plus performant, notamment lorsqu’on considère les morphèmes et non pas les mots. De plus, en faisant varier leur évaluation en fonction de la langue, le japonais nous apporte de meilleurs résultats. ABSTRACT A rich literature explores unsupervised segmentation algorithms infants could use to parse their input, mainly focusing on English, an analytic language where word, morpheme, and syllable boundaries often coincide. Synthetic languages, where words are multi-morphemic, may present unique diffi- culties for segmentation. -

1 on Agent Nominalizations and Why They Are Not Like Event

On agent nominalizations and why they are not like event nominalizations1 Mark C. Baker and Nadya Vinokurova Rutgers University and Research Institute of Humanities -Yakutsk Abstract: This paper focuses on agent-denoting nominalizations in various languages (e.g. the finder of the wallet), contrasting them with the much better studied action/event- denoting nominalizations. In particular, we show that in Sakha, Mapudungun, and English, agent-denoting nominalizations have none of the verbal features that event- denoting nominalizations sometimes have: they cannot contain adverbs, voice markers, expressions of aspect or mood, or verbal negation. An apparent exception to this generalization is that Sakha allows accusative-case marked objects in agentive nominalizations. We show that in fact the structure of agentive nominalizations in Sakha is as purely nominal as in other languages, and the difference is attributable to the rule of accusative case assignment. We explain these restrictions by arguing that agentive nominalizers have a semantics very much like the one proposed by Kratzer (1996) for Voice heads. Given this, the natural order of semantic composition implies that agentive nominalizers must combine directly with VP, just as Voice heads must. As a preliminary to testing this idea typologically, we show how a true agentive nominalization can be distinguished from a headless subject relative clause, illustrating with data from Mapudungun. We then present the results of a 34-language survey, showing that indeed none of these languages allow clause-like syntax inside a true agentive nominalization. We conclude that a generative-style investigation into the details of particular languages can be a productive source of things to look for in typological surveys. -

Polysynthetic Structures of Lowland Amazonia

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, Sat Aug 19 2017, NEWGEN Chapter 15 Polysynthetic Structures of Lowland Amazonia Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald 15.1 Lowland Amazonian languages: a backdrop The Amazon basin is an area of high linguistic diversity (rivalled only by the island of New Guinea). It comprises around 350 languages grouped into over fifteen language families, in addition to a number of isolates. The six major linguistic families of the Amazon basin are as follows. • The Arawak language family is the largest in South America in terms of its geographical spread, with over forty extant languages between the Caribbean and Argentina. Well- established subgroups include Campa in Peru and a few small North Arawak groupings in Brazil and Venezuela. Arawak languages are spoken in at least ten locations north of the River Amazon, and in at least ten south of it. European languages contain a number of loans from Arawak languages, among them hammock and tobacco. • The Tupí language family consists of about seventy languages; nine of its ten branches are spoken exclusively in Amazonia. The largest branch, Tupí- Guaraní, extends beyond the Amazonian Basin into Bolivia and Paraguay. Loans from Tupí-Guaraní languages include jaguar and jacaranda. • Carib languages number about twenty five, and are spoken in various locations in Brazil and Venezuela in northern Amazonia, and in the region of the Upper Xingu and adjacent areas of Mato Grosso in Brazil south of the River Amazon. The place name ‘Caribbean’ and the noun cannibal (a version of the ethnonym ‘Carib’) are a legacy from Carib languages. • Panoan languages number about thirty, and are spoken on the eastern side of the Andes in Peru and adjacent areas of Brazil. -

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC Peter Svenonius University of Tromsø and MIT* 1. A Class of Movements The displacements characterized in (1-2) have received a great deal of attention. (Boldface in the gloss here is simply to highlight the alternation.) (1) Scrambling (exx. from Bergsland 1997: 154) a. ... gan nagaan slukax igaaxtakum (Aleut) his.boat out.of seagull.ABS flew ‘... a seagull flew out of his boat’ b. ... quganax hlagan kugan husaqaa rock.ABS his.son on.top.of fell ‘... a rock fell on top of his son’1 (2) Object Shift (OS) a. Hann sendi sem betur fer bréfi ni ur. (Icelandic) he sent as better goes the.letter down2 b. Hann sendi bréfi sem betur fer ni ur. he sent the.letter as better goes down (Both:) ‘He fortunately sent the letter down’ * I am grateful to the University of Tromsø Faculty of Humanities for giving me leave to traipse the globe on the strength of the promise that I would write some papers, and to the MIT Department of Linguistics & Philosophy for welcoming me to breathe in their intellectually stimulating atmosphere. I would especially like to thank Noam Chomsky, Norvin Richards, and Juan Uriagereka for discussing parts of this work with me while it was underway, without implying their endorsement. Thanks also to Kleanthes Grohmann and Ora Matushansky for valuable feedback on earlier drafts, and to Ora Matushansky and Elena Guerzoni for their beneficient editorship. 1 According to Bergsland (pp. 151-153), a subject preceding an adjunct tends to be interpreted as definite (making (1b) unusual), and one following an adjunct tends to be indefinite; this is broadly consistent with the effects of scrambling cross-linguistically. -

The Antisymmetry of Syntax

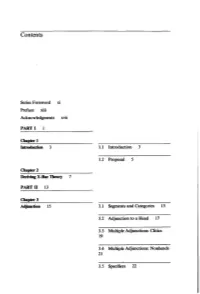

Contents Series Foreword xi Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Chapter 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Proposal 5 Chapter 2 Deriving XBar lhory 7 PART 11 13 Chapter 3 Adjunction 15 3.1 Segments and Categories 15 3.2 Adjunction to a Head 17 3.3 Multiple Adjunctions: Clitics 19 3.4 Multiple Adjunctions: Nonheads 21 3.5 Specifiers 22 ... Vlll Contents Contents 3.6 Verb-Second Effects 27 Chapter 6 3.7 Adjunction of a Head to a Nonhead 30 Coordination 57 6.1 More on Coordination 57 Chapter 4 6.2 Coordination of Heads, Wordorder 33 4.1 The specifier-complement including Clitics 59 Asymmetry 33 6.3 Coordination with With 63 4.2 Specifier-Head-Complement as a Universal Order 35 6.4 Right Node Raising 67 4.3 Time and the Universal Chapter 7 -- Specifier-Head-Complement Order Complementation 69 7.1 Multiple Complements and 36 Adjuncts 69 4.4. Linear Order and Adjunction to 7.2 Heavy NP Shift 71 Heads 38 7.3 Right-Dislocations 78 4.5 Linear Order and Structure below the Word Level 38 Relatives and Posseshes 85 8.1 Postnominal Possessives in 4.6 The Adjunction Site of Clitics English 85 42 8.2 Relative Clauses in English 86 Chapter 5 Fortherconsequences 47 5.1 There Is No Directionality 8.3 N-Final Relative Clauses 92 Parameter 47 8.4 Reduced Relatives and 5.2 The LCA Applies to All Syntactic Representations 48 Adjectives 97 8.5 More on Possessives 101 I 5.3 Agreement in Adpositional Phrases 49 1 8.6 More on French De 105 b 5.4 Head Movement 50 8.7 Nonrestrictive Relatives 1 10 5.5 Final Complementizers and Agglutination 52 .. -

1 a Microparametric Approach to the Head-Initial/Head-Final Parameter

A microparametric approach to the head-initial/head-final parameter Guglielmo Cinque Ca’ Foscari University, Venice Abstract: The fact that even the most rigid head-final and head-initial languages show inconsistencies and, more crucially, that the very languages which come closest to the ideal types (the “rigid” SOV and the VOS languages) are apparently a minority among the languages of the world, makes it plausible to explore the possibility of a microparametric approach for what is often taken to be one of the prototypical examples of macroparameter, the ‘head-initial/head-final parameter’. From this perspective, the features responsible for the different types of movement of the constituents of the unique structure of Merge from which all canonical orders derive are determined by lexical specifications of different generality: from those present on a single lexical item, to those present on lexical items belonging to a specific subclass of a certain category, or to every subclass of a certain category, or to every subclass of two or more, or all, categories, (always) with certain exceptions.1 Keywords: word order, parameters, micro-parameters, head-initial, head-final 1. Introduction. An influential conjecture concerning parameters, subsequent to the macro- parametric approach of Government and Binding theory (Chomsky 1981,6ff and passim), is that they can possibly be “restricted to formal features [of functional categories] with no interpretation at the interface” (Chomsky 1995,6) (also see Borer 1984 and Fukui 1986). This conjecture has opened the way to a microparametric approach to differences among languages, as well as to differences between related words within one and the same language (Kayne 2005,§1.2).