Running Head: CODE SWITCHING in SEQUENTIAL BILINGUALISM 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teachers' Opinions of the Assessment of Sequential Bilinguals for Primary

Teachers’ opinions of the assessment of sequential bilinguals for primary/specific language impairment in the first years of formal education in Norway Ivana Randjic Master’s Dissertation Department of Special Needs Education Faculty of Educational Sciences UNIVERSITY OF OSLO This dissertation is submitted in part fulfillment of the joint degree of MA/Mgr. Special and Inclusive Education – Erasmus Mundus University of Roehampton, University of Oslo and Charles University Autumn 2014 II III Teachers’ opinions on assessment of the assessment of sequential bilinguals for primary/specific language impairment in the first years of formal education in Norway IV © Ivana Randjic 2014 Teachers’ opinions of the assessment of sequential bilinguals for primary/specific language impairment in the first years of formal education in Norway Ivana Randjic http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo V Abstract The study was set to look into teachers’ opinions on assessment of specific (primary) language impairment (SLI/PLI) in sequential bilinguals in the first grades of formal schooling in Norway. In order to achieve the main goal of the thesis 3 research questions were posed: What are the teachers’ experiences with bilingualism in their classroom? What are the teachers’ experiences with specific (primary) language impairment? What are the teachers’ opinions on tools and procedures of this assessment? SLI/PLI is affecting a certain percentage of monolingual as well as bilingual children. In the midst of sequential bilingualism SLI/PLI may be difficult to discover. The study was interested in teachers’ perspectives of the issue. Namely, what was to be seen was how teachers cope with this practical matter of every day incidence and what their opinions on the matter were. -

Antisymmetry Kayne, Richard (1995)

CAS LX 523 Syntax II (1) A Spring 2001 March 13, 2001 qp Paul Hagstrom Week 7: Antisymmetry BE 33 Kayne, Richard (1995). The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. CDFG 1111 Koopman, Hilda (2000). The spec-head configuration. In Koopman, H., The syntax of cdef specifiers and heads. London: Routledge. (2) A node α ASYMMETRICALLY C-COMMANDS β if α c-commands β and β does not The basic proposals: c-command α. X-bar structures (universally) have a strict order: Spec-head-complement. There is no distinction between adjuncts and specifiers. • B asymmetrically c-commands F and G. There can be only one specifier. • E asymmetrically c-commands C and D. • No other non-terminal nodes asymmetrically c-command any others. But wait!—What about SOV languages? What about multiple adjunction? Answer: We’ve been analyzing these things wrong. (3) d(X) is the image of a non-terminal node X. Now, we have lots of work to do, because lots of previous analyses relied on d(X) is the set of terminal nodes dominated by node X. the availability of “head-final” structures, or multiple adjunction. • d(C) is {c}. Why make our lives so difficult? Wasn’t our old system good enough? • d(B) is {c, d}. Actually, no. • d(F) is {e}. A number of things had to be stipulated in X-bar theory (which we will review); • d(E) is {e, f}. they can all be made to follow from one general principle. • d(A) is {c, d, e, f}. The availability of a head-parameter actually fails to predict the kinds of languages that actually exist. -

Bilingual/Multilingual Handout

Bilingualism/Multilingualism Children’s Support Solutions Bilingualism/Multilingualism Worldwide, there are more people who speak two or more languages than people who speak only one language.i So, in fact, multilingualism is the norm, while learning only one language is the exception. There are many ways to learn a second or third language: one language at home and a different language at daycare, two languages at home, two languages at home and a third at school, just to name a few. Languages can be learned at the same time (simultaneous bilingualism) or one after the other (sequential bilingualism). A second language can also be learned later in childhood or even in adulthood. Being skilled in more than one language brings about many advantages which include increased employment opportunities and sharpened cognitive skills.ii Nonetheless, there are many myths surrounding multilingualism, especially when we are talking about children with delays or impairment in one or more areas of their development. childrensupportsolutions.com Myth # 1 Myth # 2 Myth # 3 Exposing my child to two or more To avoid confusing my child, people If my child is having difficulty learning languages will lead to language around him should each speak only a first language, I should not expose confusion: one language: him to a second or third language: FALSE. Children are generally FALSE. We now know that this is FALSE. Many believe that this very good at knowing which not necessary and, in fact, it is very is true because they think that language is which. Many do hard to do. Even when we think we if one language is hard, two or mix words from each language are only using one language, we more languages must be harder. -

Antisymmetry and the Lefthand in Morphology*

CatWPL 7 071-087 13/6/00 12:26 Página 71 CatWPL 7, 1999 71-87 Antisymmetry And The Lefthand In Morphology* Frank Drijkoningen Utrecht Institute of Linguistics-OTS. Department of Foreign Languages Kromme Nieuwegracht 29. 3512 HD Utrecht. The Netherlands [email protected] Received: December 13th 1998 Accepted: March 17th 1999 Abstract As Kayne (1994) has shown, the theory of antisymmetry of syntax also provides an explanation of a structural property of morphological complexes, the Righthand Head Rule. In this paper we show that an antisymmetry approach to the Righthand Head Rule eventually is to be preferred on empirical grounds, because it describes and explains the properties of a set of hitherto puzz- ling morphological processes —known as discontinuous affixation, circumfixation or parasyn- thesis. In considering these and a number of more standard morphological structures, we argue that one difference bearing on the proper balance between morphology and syntax should be re-ins- talled (re- with respect to Kayne), a difference between the antisymmetry of the syntax of mor- phology and the antisymmetry of the syntax of syntax proper. Key words: antisymmetry, Righthand Head Rule, circumfixation, parasynthesis, prefixation, category-changing prefixation, discontinuities in morphology. Resum. L’antisimetria i el costat esquerre en morfologia Com Kayne (1994) mostra, la teoria de l’antisimetria en la sintaxi també ens dóna una explicació d’una propietat estructural de complexos morfològics, la Regla del Nucli a la Dreta. En aquest article mostrem que un tractament antisimètric de la Regla del Nucli a la Dreta es prefereix even- tualment en dominis empírics, perquè descriu i explica les propietats d’una sèrie de processos fins ara morfològics —coneguts com afixació discontínua, circumfixació o parasíntesi. -

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous V. Sequential Bilingualism

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous v. Sequential Bilingualism Suzanne Flynn1, Claire Foley1 and Inna Vinnitskaya2 1MIT and 2University of Ottawa 1. Introduction Mastering multiple languages is a commonplace linguistic achievement for most of the world’s population. Chomsky (in Mukherji et al. 2000) notes that “In most of human history and in most parts of the world today, children grow up speaking a variety of languages…” Clearly, multilingualism “is just a natural state of the human mind.” Notably, most of this language learning occurs in untutored, naturalistic settings and throughout the lifespan of an individual. The false sense of language homogeneity and monolingualism that is often heralded in the United States, at least in certain regional sections, is clearly a historical artifact. As Chomsky notes: Even in the United States the idea that people speak one language is not true. Everyone grows up hearing many different languages. Sometimes they are called “dialects or stylistic variants or whatever” but they are really different languages. It is just that they are so close to each other that we don’t bother calling them different languages (Chomsky, in Mukherji et al., 2000:19 ) A conclusion is that every individual, by virtue of living within a community, is bilingual1 in some sense. Further, this means that in the same sense there is essentially universal multilingualism in the world. Despite the centrality of multilingualism to the human experience, however, questions persist concerning how learners construct new language -

Head Words and Phrases Heads and Their Dependents

Head Words and Phrases Tallerman: Chapter 4 Ling 222 - Chapter 4 1 Heads and their Dependents • Properties of heads – Head bears most important semantic information of the phrase. – Word class of head determines word class of entire phrase. • [NP very bright [N sunflowers] ] [VP [V overflowed] quite quickly] [AP very [A bright]] [AdvP quite [Adv quickly]] [PP [P inside] the house] Ling 222 - Chapter 4 2 1 – Head has same distribution as the entire phrase. • Go inside the house. Go inside. • Kim likes very bright sunflowers. Kim likes sunflowers. – Heads normally can’t be omitted • *Go the house. • *Kim likes very bright. Ling 222 - Chapter 4 3 – Heads select dependent phrases of a particular word class. • The soldiers released the hostages. • *The soldiers released. • He went into the house. *He went into. • bright sunflowers *brightly sunflowers • Kambera – Lalu mbana-na na lodu too hot-3SG the sun ‘The sun is hot.’ – *Lalu uma too house Ling 222 - Chapter 4 4 2 – Heads often require dependents to agree with grammatical features of head. • French – un livre vert a:MASC book green:MASC ‘a green book.’ – une pomme verte a:FEM apple green:FEM ‘a green apple’ – Heads may require dependent NPs to occur in a particular grammatical case. • Japanese – Kodomo-ga hon-o yon-da child-NOM book-ACC read-PAST ‘The child read the book.’ Ling 222 - Chapter 4 5 • More about dependents – Adjuncts and complements • Adjuncts are always optional; complements are frequently obligatory • Complements are selected by the head and therefore bear a close relationship with it; adjuncts add extra information. -

1 on Agent Nominalizations and Why They Are Not Like Event

On agent nominalizations and why they are not like event nominalizations1 Mark C. Baker and Nadya Vinokurova Rutgers University and Research Institute of Humanities -Yakutsk Abstract: This paper focuses on agent-denoting nominalizations in various languages (e.g. the finder of the wallet), contrasting them with the much better studied action/event- denoting nominalizations. In particular, we show that in Sakha, Mapudungun, and English, agent-denoting nominalizations have none of the verbal features that event- denoting nominalizations sometimes have: they cannot contain adverbs, voice markers, expressions of aspect or mood, or verbal negation. An apparent exception to this generalization is that Sakha allows accusative-case marked objects in agentive nominalizations. We show that in fact the structure of agentive nominalizations in Sakha is as purely nominal as in other languages, and the difference is attributable to the rule of accusative case assignment. We explain these restrictions by arguing that agentive nominalizers have a semantics very much like the one proposed by Kratzer (1996) for Voice heads. Given this, the natural order of semantic composition implies that agentive nominalizers must combine directly with VP, just as Voice heads must. As a preliminary to testing this idea typologically, we show how a true agentive nominalization can be distinguished from a headless subject relative clause, illustrating with data from Mapudungun. We then present the results of a 34-language survey, showing that indeed none of these languages allow clause-like syntax inside a true agentive nominalization. We conclude that a generative-style investigation into the details of particular languages can be a productive source of things to look for in typological surveys. -

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC Peter Svenonius University of Tromsø and MIT* 1. A Class of Movements The displacements characterized in (1-2) have received a great deal of attention. (Boldface in the gloss here is simply to highlight the alternation.) (1) Scrambling (exx. from Bergsland 1997: 154) a. ... gan nagaan slukax igaaxtakum (Aleut) his.boat out.of seagull.ABS flew ‘... a seagull flew out of his boat’ b. ... quganax hlagan kugan husaqaa rock.ABS his.son on.top.of fell ‘... a rock fell on top of his son’1 (2) Object Shift (OS) a. Hann sendi sem betur fer bréfi ni ur. (Icelandic) he sent as better goes the.letter down2 b. Hann sendi bréfi sem betur fer ni ur. he sent the.letter as better goes down (Both:) ‘He fortunately sent the letter down’ * I am grateful to the University of Tromsø Faculty of Humanities for giving me leave to traipse the globe on the strength of the promise that I would write some papers, and to the MIT Department of Linguistics & Philosophy for welcoming me to breathe in their intellectually stimulating atmosphere. I would especially like to thank Noam Chomsky, Norvin Richards, and Juan Uriagereka for discussing parts of this work with me while it was underway, without implying their endorsement. Thanks also to Kleanthes Grohmann and Ora Matushansky for valuable feedback on earlier drafts, and to Ora Matushansky and Elena Guerzoni for their beneficient editorship. 1 According to Bergsland (pp. 151-153), a subject preceding an adjunct tends to be interpreted as definite (making (1b) unusual), and one following an adjunct tends to be indefinite; this is broadly consistent with the effects of scrambling cross-linguistically. -

A Case Study of Two Chilean Bilingual Children Literatura Y Lingüística, Núm

Literatura y Lingüística ISSN: 0716-5811 [email protected] Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez Chile Goodman, David Performance Phenomena in Simultaneous and Sequential Bilinguals: a Case Study of Two Chilean Bilingual Children Literatura y Lingüística, núm. 18, 2007, pp. 219-232 Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez Santiago, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=35201813 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Literatura y Lingüística Nº18 ISSN 0716-5811 / pp. 219-232 Performance Phenomena in Simultaneous and Sequential Bilinguals: a Case Study of Two Chilean Bilingual Children David Goodman* Abstract This paper focuses on code switching and transference as produced by one simultaneous and one sequential bilingual in order to better understand some aspects of bilingualism in children due to the important role that it plays on society. This research postulates that the degree of linguistic competence influences the choice of language selected by the child when communicating. Key Words: Simultaneous and Sequential Bilingualism, Language Alternation, Code Switching, Transference Resumen Este estudio de investigación esta focalizado en code switching y transference producido por un bilingüe simultáneo y secuencial para entender mejor algunos aspectos del bilingüismo en los niños debido al papel importante que desempeñan en sociedad. Esta tesis postula que el grado de capacidad lingüística influencia la opción de la lengua seleccionada por el niño al comunicarse. Palabras clave: Bilingüismo simultaneo y secuencial, Alternación de Lenguaje, Code Switching, Transference. -

The Antisymmetry of Syntax

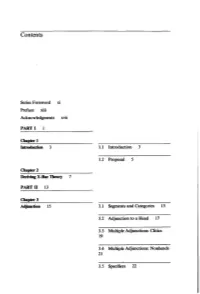

Contents Series Foreword xi Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Chapter 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Proposal 5 Chapter 2 Deriving XBar lhory 7 PART 11 13 Chapter 3 Adjunction 15 3.1 Segments and Categories 15 3.2 Adjunction to a Head 17 3.3 Multiple Adjunctions: Clitics 19 3.4 Multiple Adjunctions: Nonheads 21 3.5 Specifiers 22 ... Vlll Contents Contents 3.6 Verb-Second Effects 27 Chapter 6 3.7 Adjunction of a Head to a Nonhead 30 Coordination 57 6.1 More on Coordination 57 Chapter 4 6.2 Coordination of Heads, Wordorder 33 4.1 The specifier-complement including Clitics 59 Asymmetry 33 6.3 Coordination with With 63 4.2 Specifier-Head-Complement as a Universal Order 35 6.4 Right Node Raising 67 4.3 Time and the Universal Chapter 7 -- Specifier-Head-Complement Order Complementation 69 7.1 Multiple Complements and 36 Adjuncts 69 4.4. Linear Order and Adjunction to 7.2 Heavy NP Shift 71 Heads 38 7.3 Right-Dislocations 78 4.5 Linear Order and Structure below the Word Level 38 Relatives and Posseshes 85 8.1 Postnominal Possessives in 4.6 The Adjunction Site of Clitics English 85 42 8.2 Relative Clauses in English 86 Chapter 5 Fortherconsequences 47 5.1 There Is No Directionality 8.3 N-Final Relative Clauses 92 Parameter 47 8.4 Reduced Relatives and 5.2 The LCA Applies to All Syntactic Representations 48 Adjectives 97 8.5 More on Possessives 101 I 5.3 Agreement in Adpositional Phrases 49 1 8.6 More on French De 105 b 5.4 Head Movement 50 8.7 Nonrestrictive Relatives 1 10 5.5 Final Complementizers and Agglutination 52 .. -

Language Development in Bilingual Children Charlyne Gauthier Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 5-2012 Language Development in Bilingual Children Charlyne Gauthier Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Gauthier, Charlyne, "Language Development in Bilingual Children" (2012). Research Papers. Paper 210. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/210 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN BILINGUAL CHILDREN by Charlyne Gauthier B.S., Northern Illinois University, 2010 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree Rehabilitation Institute in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN BILINGUAL CHILDREN By Charlyne E. Gauthier A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the field of Communication Disorders Approved by: Dr. Kenneth O. Simpson, Chair Dr. Valerie E. Boyer Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Language Development in Bilingual Children……………………………… 1 Early Communication Milestones……………………………………………………………… 1 Strengths of Bilingualism…………………………………………………………………………… 5 Bilingual -

1 a Microparametric Approach to the Head-Initial/Head-Final Parameter

A microparametric approach to the head-initial/head-final parameter Guglielmo Cinque Ca’ Foscari University, Venice Abstract: The fact that even the most rigid head-final and head-initial languages show inconsistencies and, more crucially, that the very languages which come closest to the ideal types (the “rigid” SOV and the VOS languages) are apparently a minority among the languages of the world, makes it plausible to explore the possibility of a microparametric approach for what is often taken to be one of the prototypical examples of macroparameter, the ‘head-initial/head-final parameter’. From this perspective, the features responsible for the different types of movement of the constituents of the unique structure of Merge from which all canonical orders derive are determined by lexical specifications of different generality: from those present on a single lexical item, to those present on lexical items belonging to a specific subclass of a certain category, or to every subclass of a certain category, or to every subclass of two or more, or all, categories, (always) with certain exceptions.1 Keywords: word order, parameters, micro-parameters, head-initial, head-final 1. Introduction. An influential conjecture concerning parameters, subsequent to the macro- parametric approach of Government and Binding theory (Chomsky 1981,6ff and passim), is that they can possibly be “restricted to formal features [of functional categories] with no interpretation at the interface” (Chomsky 1995,6) (also see Borer 1984 and Fukui 1986). This conjecture has opened the way to a microparametric approach to differences among languages, as well as to differences between related words within one and the same language (Kayne 2005,§1.2).