Spatial Mismatch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERSPECTIVES on the INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival

PERSPECTIVES ON THE INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival L.S. Bourne Research Paper No. 94 Draft of a chapter for "The Geography of Modern Metropolitan Systems" Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbia, Ohio Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto February 1978 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives 3 2. WHAT AND WHERE IS THE INNER CITY? DEFINITIONS 5 AND CONCEPTS A Process Approach 6 A Problem Approach 9 3. DIVERSITY: THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE INNER CITY 14 Types of Inner City Neighborhoods 16 Social Disparities and the Inner City 20 Case Studies 25 4. WHY THE DECLINE OF THE INNER CITY? 30 The "Natural" Evolution Hypothesis 30 Preferences and Income: The "Pull" Hypothesis 32 The Obsolescence Hypothesis 35 The "Unintended" Policy Hypothesis 36 The Exploitation Hypothesis: Power, 40 Capitalism and the Political Economcy of Urbanization The Structural Change Hypothesis 43 The Fiscal Crisis and the Underclass Hypothesis 46 The Black Inner City in Cultural Isolation: 48 The Conflict Hypothesis Summary: Which Hypothesis of Decline is Correct? 51 5. BACK TO THE CITY: IS THE INNER CITY REVIVING? 55 6. CONCLUSIONS AND A LOOK AHEAD 63 Problems, Policies and Emerging Issues 66 Summary Comments 69 FOOTNOTES 71 REFERENCES 73 Preface The inner city is again a subject of widespread debate in most western countries. This paper undertakes to outline the nature of that debate and to document the reasons for inner city decline and revitalization. The argument is made that there is no single definition of the inner city which is universally ap plicable. -

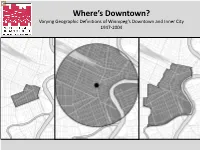

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability

sustainability Article Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability OndˇrejSlach, VojtˇechBosák, LudˇekKrtiˇcka* , Alexandr Nováˇcekand Petr Rumpel Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 709 00 Ostrava, Czechia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-731-505-314 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Urban shrinkage has become a common pathway (not only) in post-socialist cities, which represents new challenges for traditionally growth-oriented spatial planning. Though in the post-socialist area, the situation is even worse due to prevailing weak planning culture and resulting uncoordinated development. The case of the city of Ostrava illustrates how the problem of (in)efficient infrastructure operation, and maintenance, in already fragmented urban structure is exacerbated by the growing size of urban area (through low-intensity land-use) in combination with declining size of population (due to high rate of outmigration). Shrinkage, however, is, on the intra-urban level, spatially differentiated. Population, paradoxically, most intensively declines in the least financially demanding land-uses and grows in the most expensive land-uses for public administration. As population and urban structure development prove to have strong inertia, this land-use development constitutes a great challenge for a city’s future sustainability. The main objective of the paper is to explore the nexus between change in population density patterns in relation to urban shrinkage, and sustainability of public finance. Keywords: Shrinking city; Ostrava; sustainability; population density; built-up area; housing 1. Introduction The study of the urban shrinkage process has ranked among established research areas in a number of scientific disciplines [1–7]. -

Involving the Community in Inner City Renewal: a Case Study of Nanluogu in Beijing

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan Article Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing Journal of Urban Management Provided in Cooperation with: Chinese Association of Urban Management (CAUM), Taipei Suggested Citation: Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan (2012) : Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing, Journal of Urban Management, ISSN 2226-5856, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 1, Iss. 2, pp. 53-71, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2226-5856(18)30060-8 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/194394 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Historic Eastside/Springfield

Historic Eastside/Springfield Community Quality-of-Life Plan Planning Task Force: Individuals Helen Albee • Jennifer Anderson • Rickey Anderson & Guest • Michael Arbery • Shawn Ashley • April Atkins • Valerie Baham • Shakera Bailey • Nevesha Baker • Casey Barnum • Lester Bass • Lucille Battle • Annie Bean • Quinn Bell • Larry Bennett • Claudia Bentford • Jerry F. Box • Brenda Boydston • Michelle Braun • Bill Brinton • John Brooken • Tina Brooks • Justin Brown • Mickee Brown • Niki Brunson • J.F. Br yan • Co’Relous Bryant • Catherine Burkee • Richard Burnett • David Byres • Leigh Cain • Bishop Terrance Calloway • Jim Capraro • Kathleen Carignan • Katy Carigno • Wilmot Carson • Mike Cochran • Michelle Cooper • Ken Covington • Lauren Cowman • Christina Crews • Chris Cunninghan • Evan Daniels • Melissa Davis • Rose Devoe • Ty Dixon • Farand Dockett • Fran Downing • Lloyd Downing • Jacqueline Dunbar • Cathy DuPont • Vincent Edmonds • Chistina Edwards • John Fabiano • Christine Farley • Donnie Ferguson • LaTanya Ferguson • Ronnie Ferguson • Jewel Flornoy • Robert Flornoy • Geraldine Ford-Hardine • Terri Foreman • Jeff Fountain • Dr. Johnny Gaffney • Jeff Gardner • Jolee Gardner • Felicia Garrison • Kevin T. Gay • Audrey Gibson • Marion Graham • Carl Green • Kendalyn Green • Michael Hancox • Florence Handen • Al Hardin • Jacqueline Harrington • Greta Harris • Marilyn Hauser • Robert Hauser • Nathaniel Hendley • William Hoff • Bryant Holley • Joseph Howard • Taffie Hubbard • Michelle Hughes • Liz Hubbard • Samuel Hunt • Riyan Jackson • Derek Jayson • Valerie Jenkins • Carlos Johnson • Ebony Johnson • Linda Johnson • Shanita Johnson • Theresa Johnson • Faye Johnson • Joann Jones • Wayshawn Kay Jefferson • Tia Keitt • Alice Kimbrough • Riva Kimbrough • Dave Knadler • Gary Kresel • Karen Landry • Clinton Lane • Jackie Lattimore • Lucius Lattimore • Laura Lavenia • Bobby Lee • Alisha Lewis • Crystal Lewis • Jackie Littlebee • Reginald Lott • Janice R. Love • Earline Lowe • Bob Lyle • Lane Manis • Steve Manis • Monica Martin • Sabrena McCullough • Marc A. -

Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too?

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES IS URBAN DECAY BAD? IS URBAN REVITALIZATION BAD TOO? Jacob L. Vigdor Working Paper 12955 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12955 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2007 The author is grateful to Yongsuk Lee, Joshua Kinsler and Patrick Dudley for research assistance, and to Erzo F.P. Luttmer and seminar participants at Yale University, the 2006 NBER Summer Institute workshop on Public Economics and Real Estate, and at the 2005 American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association International Meeting for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Remaining errors are the author's responsibility. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Jacob L. Vigdor. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too? Jacob L. Vigdor NBER Working Paper No. 12955 March 2007 JEL No. D1,R21,R31 ABSTRACT Many observers argue that urban revitalization harms the poor, primarily by raising rents. Others argue that urban decline harms the poor by reducing job opportunities, the quality of local public services, and other neighborhood amenities. While both decay and revitalization can have negative effects if moving costs are sufficiently high, in general the impact of neighborhood change on utility depends on the strength of price responses to neighborhood quality changes. Data from the American Housing Survey are used to estimate a discrete choice model identifying households' willingness-to-pay for neighborhood quality. -

Strategic Urban Planning and Design Tools for Inner City Regeneration

Soraya Mirza. Strategic Urban Planning and Design Tools for Inner City Regeneration. 46th ISOCARP Congress 2010 Strategic Urban Planning and Design Tools for Inner City Regeneration Towards a Strategic Approach of Sustainable Urban Form Future The Case of Bandung City, Indonesia Soraya Mirza Introduction The recent debate in developed countries on environmental degradation is focusing on the impact of urban development to global environment. Even though the urban problems are generally known, there are still complexities and differences of urban experience from each cities contributing to the environmental issues. Many scholars argued that a sustainable urban form is a key to achieving a sustainable development. Cities appear as important locations for setting up actions to help the goals of sustainable development (Jenks et al , 1996). Developed countries have elaborated regeneration policies to tackle the decline of their inner city areas. These policies may include tax and financial incentives, loans, grants and land use regulations to promote development and attract new economic activities or to reinforce existing ones; new housing schemes and the rehabilitation of existing ones; environmental improvements and policies to promote the conservation of historic buildings (Nobre Cuce, 1994). In general regeneration takes place in the inner city area where the economic activities are concentrated.The study of inner city regeneration had been recognized in Europe from the late 1960s and gradually the western European cities moved from tackling the problem of obsolete housing through policies of mass slum clearance and replacement to more sensitive programs of housing renovation and area improvement (Couch et al, 2003). Jenks et al (1996) mentioned the significance of the developed countries efforts to find solution should also be concentrated in developing countries which have such overwhelming problems. -

Does Urban Sprawl Further Spatially Isolate Blacks from Jobs

Institute for Research on Poverty Discussion Paper no. 1304-05 Job Sprawl, Spatial Mismatch, and Black Employment Disadvantage Michael A. Stoll Department of Public Policy UCLA School of Public Affairs E-mail: [email protected] July 2005 The author would like to thank Kenya Covington, Steven Raphael, and J.R. Deshazo for helpful comments on earlier drafts of the paper, and Portia Pedro for invaluable research assistance. The author would also like to thank Matthew E. Kahn, Stephen Malpezzi, and Jordon Rappaport for providing some of the data used in the analysis. IRP Publications (discussion papers, special reports, and the newsletter Focus) are available on the Internet. The IRP Web site can be accessed at the following address: http://www.irp.wisc.edu Abstract This paper examines the relationship between job sprawl and the spatial mismatch between blacks and jobs. Using data from a variety of sources including the U.S. Census and the ZIP Code Business Patterns of the U.S. Department of Commerce, I control extensively for metropolitan area characteristics and other factors. In addition, I use metropolitan area physical geography characteristics as instruments for job sprawl to address the problem of simultaneity bias. I find a significant and positive effect of job sprawl on mismatch conditions faced by blacks that remains evident across a variety of model specifications. This effect is particularly important in the Midwest and West, and in metropolitan areas where blacks’ share of the population is not large and where blacks’ population growth rate is relatively low. The results also indicate that the measure of mismatch used in this analysis is highly correlated across metropolitan areas, with blacks’ employment outcomes in the expected direction. -

Causes of Inner-City Poverty: Eight Hypotheses in Search of Reality

The Causes of Inner-City Poverty: Eight Hypotheses in Search of Reality The Causes of Inner-City Poverty: Eight Hypotheses in Search of Reality Michael B. Teitz Public Policy Institute of California and University of California, Berkeley Karen Chapple University of California, Berkeley Abstract Over the past 40 years, poverty among the inhabitants of U.S. inner cities has remained stubbornly resistant to public policy prescriptions. Especially for African Americans and Latinos, the gap between their economic well-being and that of the mainstream has widened despite persistent and repeated efforts to address the prob- lem. At the same time, a continuing stream of research has sought to explain urban poverty, with a wide variety of explanations put forward as the basis for policy. This paper reviews that research, organizing it according to eight major explanations or hypotheses: structural shifts in the economy, inadequate human capital, racial and gender discrimination, adverse cultural and behavioral factors, racial and income segregation, impacts of migration, lack of endogenous growth, and adverse conse- quences of public policy. We conclude that all of the explanations may be relevant to urban poverty but that their significance and the degree to which they are well supported varies substantially. It is now more than 12 years since the publication of William J. Wilson and Robert Aponte’s (1985) survey of urban poverty in the United States. That report still stands alone as an effort to produce “a state of the art review of research and theoretical writing on urban poverty” (Wilson and Aponte, 1985). However, in the intervening years, there has been much work on and even more debate about the nature and causes of poverty in U.S. -

Compare and Contrast the Concentric, Sector and Multiple Nuclei Models

KEY Compare and contrast the Concentric, Sector and Multiple nuclei models The Concentric, Sector models and multiple nuclei models have many features in common: 1) Both models focus on importance of accessibility. The centrally located C.B.D. is the most accessible and its land value or rent-bid is the highest. 2) Distant decay theory is applicable in both models. Land value and population density decline with distance from the central places. 3) There are clear-cut and abrupt boundaries between the land-use zones. 4) Both concern the study of ground-floor functions instead of the three-dimensional study as height of buildings is neglected 5) Residential segregation Social-economic status segregates residential areas. The lower-income groups live in the inner city which is suffering from urban decay or in areas near the factory zone. Nearness to working places reduces time and cost of transport, but gives better working opportunities and easiness of obtaining various order of goods and services. In contrast, the higher- income groups occupy the urban periphery with better living environment far away from the factory zone and the lower-income groups. Their implicit assumptions are: 1) Great variation in characteristics e.g. heterogeneity of the population in culture and society. 2) Competition for centrality because of limited space leading to highest land value. The opposite is true of peripheral areas. 3) City centre being centre of employment. 4) Commercial and industrial base to the economy of the city. 5) Private ownership of property and capitalist mode of competition for space. 6) Expanding area and population of the city by invasion and succession. -

The Slow Death of Great Cities? Urban Abandonment Or Urban Renaissance

The slow death of great cities? Urban abandonment or urban renaissance Anne Power and Katharine Mumford The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has supported this project as part of its programme of research and innovative development projects, which it hopes will be of value to policy makers and practitioners. The facts presented and views expressed in this report are, however, those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Foundation. Photographs are Anthony Lee (LSE Housing) and Katharine Mumford The flyer on page 34 is reproduced courtesy of City of Newcastle upon Tyne Housing Department; the photographs on page 79 are reproduced courtesy of Urban Splash; Appendix 6 is reproduced courtesy of Manchester City Council. Joseph Rowntree Foundation 1999 All rights reserved. Published for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation by YPS ISBN 1 902633 11 3 Cover design by Adkins Design Prepared and printed by: York Publishing Services Ltd 64 Hallfield Road Layerthorpe York YO31 7ZQ Contents Page Acknowledgements vi Definitions vii Executive summary ix 1 Introduction – urban abandonment or urban renaissance? 1 Part I Trends in two cities and four neighbourhoods 3 2 Method and approach 5 3 Changes in the two cities and four neighbourhoods 8 Population 8 Density 10 Jobs 10 4 Social dynamics 13 Deprivation 13 Concentrated deprivation 14 Ethnic composition 15 Crime 15 5 Housing patterns – how problematic are they? 17 Tenure 17 Changing housing patterns 18 Housing types 20 Part II Evidence of incipient abandonment 23 6 Urban abandonment 25 Empty property 25 -

1.4 Shrinking Cities

1.4 Shrinking Cities he history of cities has not been dictated exclusively per cent of the sample, experienced a reduction in population by urban growth; a long-term perspective on (i.e., recorded negative growth rates) between 1990 and 2000. demographic and economic changes, particularly Rapid or accelerated urban growth is still the norm in most in the developed world, shows that, historically, regions of the developing world, however: more than half of citiesT have experienced boom and bust cycles over time, and the cities in the sample (53 per cent) have been growing at an in some places, decline and population contraction result in accelerated or rapid pace since the 1990s2; 17 per cent of these permanent alterations to city structures. cities experienced an accelerated growth rate of more than 4 Cities may expand or contract in size and importance; their per cent per year, while 36 per cent saw rapid annual growth growth and decline is dependent on a variety of historical, rates of between 2 and 4 per cent). economic, political, and demographic factors. While some It may seem paradoxical that in a period of rapid urban cities are growing more rapidly than others, the widespread growth, some cities in the developing world are actually assumption that increasing global urbanization means that all shrinking. The negative growth trend is largely associated cities are growing is false; in fact, evidence shows that in all with cities in North America and Europe, where the number regions of the world, and especially in the developed regions, of shrinking cities has increased faster in the last 50 years many cities are actually shrinking in size.