Rethinking Shrinking Cities: Peripheral Dual Cities Have Arrived

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 8 Central Business District Downtown Capital District Master Plan Trenton, New Jersey CHAPTER 8: Central Business District

Chapter 8 Central Business District Downtown Capital District Master Plan Trenton, New Jersey CHAPTER 8: Central Business District Central Business District The Central Business District of Downtown Trenton located along State, Broad and Warren Streets will be reinvigorated as a new employment center, shopping and entertainment destination, and residential community of choice. Description Trenton’s historic Central Business District is located along East State, North Broad and North Warren Streets. This district is generally bounded by the Assunpink Creek and Front Street on the south, the intersection of Central Business Clinton and State Street on the east, the Battle Monument on the north, District and Warren and Willow Streets on the west. This district is fortunate in that a large number of its original buildings are intact. In some cases though, entire blocks have been demolished and redeveloped with large office complexes that are used primarily by state government. The South Warren Street Historic District is located in this district, adjacent to the Trenton Marriot Lafayette Yard hotel. Parking structures are distributed throughout this district and there is limited on-street parking. Page 60 CHAPTER 8: Central Business District Existing Land Use – Land use within the Central Business District includes a mix Current Configuration – The Central Business District was historically of historic-scaled, mixed-use structures, new large-scale office complexes, parking comprised of three- and four-story mixed-use buildings along with tall landmark structures, hotel, institutional buildings and pocket parks. buildings such as Broad Street Bank. The demolition and redevelopment of entire blocks for large-scale office uses has been the trend in recent years. -

PERSPECTIVES on the INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival

PERSPECTIVES ON THE INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival L.S. Bourne Research Paper No. 94 Draft of a chapter for "The Geography of Modern Metropolitan Systems" Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbia, Ohio Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto February 1978 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives 3 2. WHAT AND WHERE IS THE INNER CITY? DEFINITIONS 5 AND CONCEPTS A Process Approach 6 A Problem Approach 9 3. DIVERSITY: THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE INNER CITY 14 Types of Inner City Neighborhoods 16 Social Disparities and the Inner City 20 Case Studies 25 4. WHY THE DECLINE OF THE INNER CITY? 30 The "Natural" Evolution Hypothesis 30 Preferences and Income: The "Pull" Hypothesis 32 The Obsolescence Hypothesis 35 The "Unintended" Policy Hypothesis 36 The Exploitation Hypothesis: Power, 40 Capitalism and the Political Economcy of Urbanization The Structural Change Hypothesis 43 The Fiscal Crisis and the Underclass Hypothesis 46 The Black Inner City in Cultural Isolation: 48 The Conflict Hypothesis Summary: Which Hypothesis of Decline is Correct? 51 5. BACK TO THE CITY: IS THE INNER CITY REVIVING? 55 6. CONCLUSIONS AND A LOOK AHEAD 63 Problems, Policies and Emerging Issues 66 Summary Comments 69 FOOTNOTES 71 REFERENCES 73 Preface The inner city is again a subject of widespread debate in most western countries. This paper undertakes to outline the nature of that debate and to document the reasons for inner city decline and revitalization. The argument is made that there is no single definition of the inner city which is universally ap plicable. -

Concentric Zone Theory

Lecture-04 M.A.(Semester-II) PAPER-8 Urban Sociology CONCENTRIC ZONE THEORY Dr. Shankar Kumar Lal University Department of Sociology Lalit Narayan Mithila University Kameshwarnagar,Darbhanga E-mail: [email protected] Mobile: +91-8252199182 CONCENTRIC ZONE THEORY ORIGIN . Developed in the 1920’s by Ernest Burgess and Robert Park, University of Chicago . Hypothesis of this theory is that cities grow and develop outwardly in concentric zones. Sought to explain the socioeconomic divides in and out of the city . Model was based on Chicago’s city layout . First theory to explain the distribution of social groups CONCENTRIC ZONE THEORY….? • Social structures extend outward from one central business area. • Population density decreases towards outward zones • Shows correlation between socioeconomic status and the distance from the central business district • Also known as the Burgess Model, the Bull’s Eye Model, the Concentric Ring Model, or the Concentric Circles Model. Concentric Zone Model ZONE 1: CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT(CBD) • Non-residential center for business. • “Downtown” area • Emphasis on business and commerce • Commuted to by residents of other zones Commercial centre . First, the inner most ring zone or nucleolus of the city is a commercial centre also called Central Business District (CBD) in North America and western countries. This zone is characterized by high intensity of commercial, social and civic amenities. It is the heart of the city which includes department stores, office buildings, shops, banks, clubs, hotels, theatres and many other civic buildings. Being the centre of commercial activities and location, it is accessible from all directions and attracts a large number of people. -

Downtown Development Coordinator 919.753.1040 [email protected] WOODLAND DR

DOWNTOWN QUICK FACTS Transportation Schools NC Highway 42 & 401 Fuquay-Varina Middle School 8 miles from Wake Technical Community College Fuquay-Varina High School 15 miles from Campbell University 20 miles from NC State University 27 Miles from RDU International Airport NC Main Street Parks Fuquay-Varina is proud to be part of the North Action Park Library Park Carolina Main Street program. This program works to Centennial Park Mineral Springs Park stimulate economic development within the context Falcon Park of historic preservation, using a comprehensive approach to downtown revitalization. Zoning Downtown Center 1 District (DC-1) & Downtown Center 2 District (DC-2) were created as part of the Town Center Plan to encourage vertical mixed-use development that attracts live, work and visit projects to Fuquay-Varina’s downtown. FOR MORE INFORMATION: Casey Verburg Downtown Development Coordinator 919.753.1040 [email protected] www.fuquay-varina.org/downtown WOODLAND DR T T S AREAS OF INTEREST T O S R Y O B M Development Public S E Spring Avenue Townhomes Downtown Area T D T W JONES S DO I A Opportunity Park T P C Construction has begun on a three-quarter of an A acre site T S W Fuquay Springs Development P Public located centrally in the Fuquay district of downtown Historic District DP DEPO Project Parking Area Fuquay-Varina. This lot will house downtown’s R SEA SUNSET DR N WES D T ST S N. Main Street Mixed Use Development KITE DR D newest residential project with 15 new townhomes T L N WES ON DR EXISTING STRUCTURES O T ST N T The Town of Fuquay-Varina has recently gained site control of Y E on the corner of Spring Avenue and Vance Street. -

Downtown East Re-Urbanization Strategy Executive Summary 1St St Nw St 1St North Cap I Tol St 4Th St Nw St 4Th

AUGUST 2019 D O W N T O W N RE-URBANIZATION E A S T STRATEGY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Dear Residents and Stakeholders: As Mayor of Washington, DC, I am pleased to In addition to thanking the residents who present our Downtown East Re-Urbanization contributed to this plan, I would like to Strategy. Located on the iconic doorstep acknowledge the DC Office of Planning for of Union Station and the crossroads of our leading the effort along with several District Downtown, Mount Vernon Triangle, and NoMA agencies, including the District Department neighborhoods, Downtown East represents a of Transportation, the District Department of bustling gateway to our city’s geographic heart. Parks and Recreation, the District Department of General Services, and the District Department of Over the past few decades, much of our center city Energy and the Environment. This core team of area has witnessed a resurgence of investment partner agencies has, over the past several years, and opportunity, while Downtown East has engaged with residents, partners in the federal largely lagged. Now, however, the area is poised government, and community stakeholders to to bloom, with renewed interest, a growing establish this future for Downtown East. Moving population, large-scale development (complete forward, this Strategy will require a range of or under construction), and transformative public implementers across many sectors. The District space projects—like the New Jersey/New York government, the Mt. Vernon Triangle Community Avenue Streetscape project—which attempts to Improvement District (CID), the NoMA Business heal physical barriers and is expected to provide Improvement District (BID), the Downtown BID, safe pedestrian connections and a vibrant place property owners, developers, civic associations, for all our residents and visitors to enjoy. -

The Restructuring of Detroit: City Block Form Change in a Shrinking City, 1900–2000

URBAN DESIGN International (2008) 13, 156–168 r 2008 Palgrave Macmillan. 1357-5317/08 www.palgrave-journals.com/udi The restructuring of Detroit: City block form change in a shrinking city, 1900–2000 Brent D. Ryan* Department of Urban Planning and Design, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 48 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA This paper examines the dramatic changes to city block morphology that occurred during the 20th century in Detroit, MI, USA. The study area is comprised of four square miles (10.4 km2) of downtown Detroit. The paper measures the amount and causes of city block frontage change between the years 1896 and 2002, and finds that 37% of Detroit’s 1896 city block frontage was removed by 2002. Only 50% of the removed frontage was replaced with new frontage. The city block changes indicate a consistent replacement of small blocks and their intervening streets with larger superblocks with few or no cross streets. Almost 50% of city block frontage removal was attributable to slum clearance or ‘urban renewal’ and highway (motorway) construction. Smaller amounts of block reconfiguration were due to large-scale building (megaproject) construction, street widening, and block consolidation for industrial, institutional, and parking-related uses. The recent city block restructuring resulting from new megaprojects indicates that the further replacement of Detroit’s 19th-century street and block structure by superblocks is likely. Urban Design International (2008) 13, 156–168. doi:10.1057/udi.2008.21 Keywords: Detroit; downtown; urban morphology; urban redevelopment; shrinking cities Introduction During the 20th century, the downtowns of American cities experienced physical restructur- Many cities have experienced the significant ing as extensive as that of any war-damaged city redevelopment and redesign of their central areas. -

Bryan Downtown Master Plan 1-11

DOWNTOWN BRYAN MASTER PLAN Bryan, Texas September 2001 Prepared for Contents i. Executive Summary 1. Purpose & Methodology Bryan City Council Existing Condition Analysis 2. Existing Physical Framework · 3. Existing Streets & Parking Downtown Action Committee Planning and Zoning Commission 4. Existing Gateways & Landmarks 5. Economic Context 6. Socio- Economic Context 7. Public Policy Context Public Input 8. Market Survey Results 9. Public Input Results 10. Public Input Results 11. Charrette Workshop Physical Master Plan 12. Concept Plan 13. Civic District Plan 14. Land Use Plan 15. Restoration & Infill Opportunities 16. Access & Parking Streetscape Design 17. Model Parking Lot Redesign 18. Streetscape Master Plan 19. Streetscape Segment “A” 20. Streetscape Segment “B” 21. Streetscape Segment “C” 22. Streetscape Segment “D” 23. Streetscape Segment “E” 24. Streetscape Segment “F” 25. Streetscape Segment “G” 26. Secondary Streetscape Segments 27. Streetscape Furnishings, Shade Trees & Waste Management Utilities & Infrastructure 28. Existing Downtown Lighting 29. Downtown Lighting Recommendations 30. Existing Infrastructure 31. Infrastructure Recommendations 32. Utility Corridor Locations Urban Design 33. Public Spaces, Entry Corridors & Gateways 34. Public Spaces, Entry Corridors & Gateways 35. Urban & Architectural Design Recommendations Economic & Market Strategy 36. Market Repositioning 37. Tenant Mix 38. Downtown Management 39. Business Development 40. Marketing 41. Special Events & Promotions 42. Performing Arts Implementation 43. Historic -

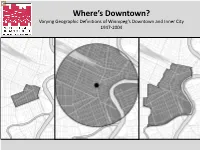

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Suburban Growth and Downtown Decline in Ontario's Mid-Sized Cities

Leveraging Ontario’s Urban Potential: Mid-Sized Cities Research Series Transportation & Land Use Suburban Growth and Downtown Decline in Ontario’s Mid-Sized Cities David Gordon, School of Urban and Regional Planning, Geography and Planning, Queen’s University SUBURBAN GROWTH AND DOWNTOWN DECLINE IN ONTARIO’S MID-SIZED CITIES Introduction combined with inner-city school closures and the decline of downtown business districts. In the worst cases, there can even be vacant downtown stores Ontario’s mid-sized metropolitan areas1 are mainly and abandoned inner-city housing, similar to recent composed of suburban neighbourhoods2. Only about problems in Saint John NB. 12% of the 2011 population in Ontario’s mid-sized metro areas lived in dense, walkable active core This paper will place the structure and growth of Ontario’s neighbourhoods (such as downtowns), while the mid-sized cities in a national context. It will also briefly rest lived in some form of suburb, as defined in the discuss policy implications of downtown decline combined sections below. Suburban sprawl is considered to be with suburban development and growth. an unsustainable form of development, and can have negative impacts on economic, environmental, and public health indicators. Analysis The pattern of population growth in Ontario’s mid- sized metropolitan areas is strongly focused in the suburbs, where almost all population growth happened Auto in Automobile Suburbs and Exurbs. In contrast, the 68% Suburb total population in Active Core neighbourhoods in the downtowns and inner cities declined across Exurban the province. These inner city neighbourhoods are Ontario 12% the historic hearts of their metropolitan areas, and Medium Sized their declines can have both symbolic and economic Metropolitan consequences. -

Destination Downtown Vision Plan

Where Meridian Lives Th e Vision Destination: Downtown Thanks to the following sponsors for their generous help in publishing this report: Sponsors: Where Meridian Lives Destination: Downtown Destination: Downtown Crafted in early 2010, is a Vision will accommodate automobiles and provide efficient and A VISION FOR DOWNTOWN MERIDIAN Destination: Downtown Plan for the long-term future of downtown Meridian. This convenient parking. On-street parking, structured parking document illustrates the overall Vision for the future of and surface parking lots will be convenient and used where downtown through images and text, and is accompanied by appropriate to bring patrons close to businesses, retail Implementing the Vision, which identifies specific projects outlets, and homes. A balanced retail environment which and implementation strategies for achieving that vision. includes a mix of businesses, specialty stores, retail outlets, Two other supporting documents, the Market Analysis and restaurants, professional services and institutions is also the Parking Analysis, offer background and more detail on envisioned for the downtown. New retail activity will not specific findings and recommendations. jeopardize existing businesses but coexist with, and support them. VISION VISION FRAMEWORK MAP The City of Meridian’s slogan,“Built for Business - Designed for Living,” embodies the community’s character as a The downtown Vision is primarily focused on creating a sophisticated, family-friendly city in the heart of the Treasure mixed-use urban environment. To this end, a number of Valley. The downtown Vision reinforces this mind-set character districts are proposed within the MDC Urban and helps to achieve it. Meridian’s downtown will be a Renewal Area (URA) boundary. -

Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability

sustainability Article Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability OndˇrejSlach, VojtˇechBosák, LudˇekKrtiˇcka* , Alexandr Nováˇcekand Petr Rumpel Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 709 00 Ostrava, Czechia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-731-505-314 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Urban shrinkage has become a common pathway (not only) in post-socialist cities, which represents new challenges for traditionally growth-oriented spatial planning. Though in the post-socialist area, the situation is even worse due to prevailing weak planning culture and resulting uncoordinated development. The case of the city of Ostrava illustrates how the problem of (in)efficient infrastructure operation, and maintenance, in already fragmented urban structure is exacerbated by the growing size of urban area (through low-intensity land-use) in combination with declining size of population (due to high rate of outmigration). Shrinkage, however, is, on the intra-urban level, spatially differentiated. Population, paradoxically, most intensively declines in the least financially demanding land-uses and grows in the most expensive land-uses for public administration. As population and urban structure development prove to have strong inertia, this land-use development constitutes a great challenge for a city’s future sustainability. The main objective of the paper is to explore the nexus between change in population density patterns in relation to urban shrinkage, and sustainability of public finance. Keywords: Shrinking city; Ostrava; sustainability; population density; built-up area; housing 1. Introduction The study of the urban shrinkage process has ranked among established research areas in a number of scientific disciplines [1–7]. -

Urban Reform and Shrinking City Hypotheses on the Global City Tokyo

Urban Reform and Shrinking City Hypotheses on the Global City Tokyo Hiroshige TANAKA Professor of Economic Faculty in Chuo University, 742-1Higashinakano Hachioji city Tokyo 192-0393, Japan. Chiharu TANAKA1 Manager, Mitsubishi UFJ Kokusai Asset Management Co.,Ltd.,1-12-1 Yurakucho, Chiyodaku, Tokyo 100-0006, Japan. Abstract The relative advantage among industries has changed remarkably and is expected to bring the alternatives of progressive and declining urban structural change. The emerging industries to utilize ICT, AI, IoT, financial and green technologies foster the social innovation connected with reforming the urban structure. The hypotheses of the shrinking city forecast that the decline of main industries has brought the various urban problems including problems of employment and infrastructure. But the strin- gent budget restriction makes limit the region on the social and market system that the government propels the replacement of industries and urban infrastructures. By developing the two markets model of urban structural changes based on Tanaka (1994) and (2013), we make clear theoretically and empirically that the social inno- vation could bring spreading effects within the limited area of the region, and that the social and economic network structure prevents the entire region from corrupting. The results of this model analysis are investigated by moves of the municipal average income par taxpayer of the Tokyo Area in the period of 2011 to 2014 experimentally. Key words: a new type of industrial revolution, shrinking city, social innovation, the connectivity of the Tokyo Area, urban infrastructures. 1. Introduction The policies to liberalize economies in the 1990s have accelerated enlargement of the 1 C.