Shrinking Cities, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERSPECTIVES on the INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival

PERSPECTIVES ON THE INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival L.S. Bourne Research Paper No. 94 Draft of a chapter for "The Geography of Modern Metropolitan Systems" Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbia, Ohio Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto February 1978 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives 3 2. WHAT AND WHERE IS THE INNER CITY? DEFINITIONS 5 AND CONCEPTS A Process Approach 6 A Problem Approach 9 3. DIVERSITY: THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE INNER CITY 14 Types of Inner City Neighborhoods 16 Social Disparities and the Inner City 20 Case Studies 25 4. WHY THE DECLINE OF THE INNER CITY? 30 The "Natural" Evolution Hypothesis 30 Preferences and Income: The "Pull" Hypothesis 32 The Obsolescence Hypothesis 35 The "Unintended" Policy Hypothesis 36 The Exploitation Hypothesis: Power, 40 Capitalism and the Political Economcy of Urbanization The Structural Change Hypothesis 43 The Fiscal Crisis and the Underclass Hypothesis 46 The Black Inner City in Cultural Isolation: 48 The Conflict Hypothesis Summary: Which Hypothesis of Decline is Correct? 51 5. BACK TO THE CITY: IS THE INNER CITY REVIVING? 55 6. CONCLUSIONS AND A LOOK AHEAD 63 Problems, Policies and Emerging Issues 66 Summary Comments 69 FOOTNOTES 71 REFERENCES 73 Preface The inner city is again a subject of widespread debate in most western countries. This paper undertakes to outline the nature of that debate and to document the reasons for inner city decline and revitalization. The argument is made that there is no single definition of the inner city which is universally ap plicable. -

The Restructuring of Detroit: City Block Form Change in a Shrinking City, 1900–2000

URBAN DESIGN International (2008) 13, 156–168 r 2008 Palgrave Macmillan. 1357-5317/08 www.palgrave-journals.com/udi The restructuring of Detroit: City block form change in a shrinking city, 1900–2000 Brent D. Ryan* Department of Urban Planning and Design, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 48 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA This paper examines the dramatic changes to city block morphology that occurred during the 20th century in Detroit, MI, USA. The study area is comprised of four square miles (10.4 km2) of downtown Detroit. The paper measures the amount and causes of city block frontage change between the years 1896 and 2002, and finds that 37% of Detroit’s 1896 city block frontage was removed by 2002. Only 50% of the removed frontage was replaced with new frontage. The city block changes indicate a consistent replacement of small blocks and their intervening streets with larger superblocks with few or no cross streets. Almost 50% of city block frontage removal was attributable to slum clearance or ‘urban renewal’ and highway (motorway) construction. Smaller amounts of block reconfiguration were due to large-scale building (megaproject) construction, street widening, and block consolidation for industrial, institutional, and parking-related uses. The recent city block restructuring resulting from new megaprojects indicates that the further replacement of Detroit’s 19th-century street and block structure by superblocks is likely. Urban Design International (2008) 13, 156–168. doi:10.1057/udi.2008.21 Keywords: Detroit; downtown; urban morphology; urban redevelopment; shrinking cities Introduction During the 20th century, the downtowns of American cities experienced physical restructur- Many cities have experienced the significant ing as extensive as that of any war-damaged city redevelopment and redesign of their central areas. -

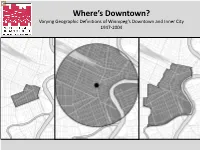

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability

sustainability Article Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability OndˇrejSlach, VojtˇechBosák, LudˇekKrtiˇcka* , Alexandr Nováˇcekand Petr Rumpel Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 709 00 Ostrava, Czechia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-731-505-314 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Urban shrinkage has become a common pathway (not only) in post-socialist cities, which represents new challenges for traditionally growth-oriented spatial planning. Though in the post-socialist area, the situation is even worse due to prevailing weak planning culture and resulting uncoordinated development. The case of the city of Ostrava illustrates how the problem of (in)efficient infrastructure operation, and maintenance, in already fragmented urban structure is exacerbated by the growing size of urban area (through low-intensity land-use) in combination with declining size of population (due to high rate of outmigration). Shrinkage, however, is, on the intra-urban level, spatially differentiated. Population, paradoxically, most intensively declines in the least financially demanding land-uses and grows in the most expensive land-uses for public administration. As population and urban structure development prove to have strong inertia, this land-use development constitutes a great challenge for a city’s future sustainability. The main objective of the paper is to explore the nexus between change in population density patterns in relation to urban shrinkage, and sustainability of public finance. Keywords: Shrinking city; Ostrava; sustainability; population density; built-up area; housing 1. Introduction The study of the urban shrinkage process has ranked among established research areas in a number of scientific disciplines [1–7]. -

Urban Reform and Shrinking City Hypotheses on the Global City Tokyo

Urban Reform and Shrinking City Hypotheses on the Global City Tokyo Hiroshige TANAKA Professor of Economic Faculty in Chuo University, 742-1Higashinakano Hachioji city Tokyo 192-0393, Japan. Chiharu TANAKA1 Manager, Mitsubishi UFJ Kokusai Asset Management Co.,Ltd.,1-12-1 Yurakucho, Chiyodaku, Tokyo 100-0006, Japan. Abstract The relative advantage among industries has changed remarkably and is expected to bring the alternatives of progressive and declining urban structural change. The emerging industries to utilize ICT, AI, IoT, financial and green technologies foster the social innovation connected with reforming the urban structure. The hypotheses of the shrinking city forecast that the decline of main industries has brought the various urban problems including problems of employment and infrastructure. But the strin- gent budget restriction makes limit the region on the social and market system that the government propels the replacement of industries and urban infrastructures. By developing the two markets model of urban structural changes based on Tanaka (1994) and (2013), we make clear theoretically and empirically that the social inno- vation could bring spreading effects within the limited area of the region, and that the social and economic network structure prevents the entire region from corrupting. The results of this model analysis are investigated by moves of the municipal average income par taxpayer of the Tokyo Area in the period of 2011 to 2014 experimentally. Key words: a new type of industrial revolution, shrinking city, social innovation, the connectivity of the Tokyo Area, urban infrastructures. 1. Introduction The policies to liberalize economies in the 1990s have accelerated enlargement of the 1 C. -

Involving the Community in Inner City Renewal: a Case Study of Nanluogu in Beijing

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan Article Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing Journal of Urban Management Provided in Cooperation with: Chinese Association of Urban Management (CAUM), Taipei Suggested Citation: Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan (2012) : Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing, Journal of Urban Management, ISSN 2226-5856, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 1, Iss. 2, pp. 53-71, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2226-5856(18)30060-8 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/194394 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Shrinking Cities, Right Sizing, and Neighborhood Change

ABSTRACT THE GEOGRAPHY OF URBAN AMERICA: SHRINKING CITIES, RIGHT SIZING, AND NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGE Michael W. Ribant, PhD Department of Geographic and Atmospheric Sciences Northern Illinois University, 2018 Xuwei Chen, Director Hundreds of U.S. cities, termed shrinking cities, suffered notable population loss during the period of 1910-2010. The effects of such urban depopulation range from minor problems associated with a weakened tax base or housing market, to major problems associated with widespread abandonment and dereliction. A shrinking city literature that began in the mid-2000s has grown significantly in recent years, however, it still struggles with defining which cities belong in the shrinking city discussion, how urban systems unfold within a shrinking city, and what strategies are best to put forth to rectify their problems. The objective of this research is to understand how multidimensional urban processes unfold in shrinking U. S. cities across different scales. Specifically, this research aims to 1) develop a better understanding of the types of shrinking cities in the U.S., 2) examine the efficacy of right-sizing strategies in an iconic shrinking central city, and 3) understand how neighborhood change spatially manifests in a metropolitan area anchored by a large central city. To achieve those goals, this dissertation conducted studies on shrinking cities at different scales by 1) developing a shrinking city typology to help differentiate and illustrate heterogenous clusters of shrinking cities, 2) analyzing the property tax foreclosure and auction process of the nation’s most iconic shrinking city, Detroit, and 3) examining the spatial patterns of variables associated with income ascent and decline within the largest shrinking city in the country, Chicago. -

FINAL PROJECT REPORT Of

Development of Heat Island Dataset for Las Vegas Urban Canopy CityGreen Analysis FINAL PROJECT REPORT of Development of Heat Island Dataset for Las Vegas Urban Canopy CityGreen Analysis Dated: February 22, 2013 Funded by: Nevada Division of Forestry with a grant from US Forest Service Completed by: University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, Nevada PIs: Haroon Stephen (Civil and Environmental Engineering) Craig Palmer (Harry Reid Center for Environmental Studies) Sajjad Ahmad (Civil and Environmental Engineering) Graduate Student: Adam Black This project is funded through grants from the US Forest Service. NDF and USFS are equal opportunity service providers. “In accordance with Federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture policy, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) To file a complaint of discrimination: write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326- W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.” 1 Development of Heat Island Dataset for Las Vegas Urban Canopy CityGreen Analysis Executive Summary Las Vegas has almost doubled its population during the last two decades and undergone exponential urban sprawl. The urban growth brings about changes that adversely impact the quality of urban life. The urban heat island (UHI) effect is a common problem of present day growing cities. In order to take measures for UHI reduction, it is imperative that the UHI hotspots are mapped and related to landcover characteristics. -

Shrinking Cities in Japan 日本における都市の縮小 III

3. ------------------------------------- Shrinking Cities in Japan 日本における都市の縮小 III. SHRINKING CITIES IN JAPAN / 日本における都市の縮小 3 Shrinking Cities in Japan: Between Megalopolises and Rural Peripheries / 日本にお ける都市の縮小:メガ都市と地方の郊外 | Winfried Flüchter 9 Shrinkage in Japan/ 日本における縮小現象 | Yasuyuki Fujii 13 Population Aging and Japan’s Declining Rural Cities/ 人口の高齢化と廃れてゆく日 本の地方都市 | John W. Traphagan 18 Depopulation problem in rural areas as an urban problem: need of urban-rural commu- nication/ 都市問題としての地方の過疎問題:都市・地方間のコミュニケーショ ンの必要性 | Yutuka Motohashi 23 Shrinking City Phenomena of Japan in Macro-Perspective/ マクロな視点から見た 日本における都市の縮小 | Keiro Hattori III Shrinking Cities in Japan | Between Megalopolises and Rural Peripheries III | 3 SHRINKING CITIES IN JAPAN: BETWEEN MEGALOPOLISES AND RURAL PERIPHERIES Winfried Flüchter Japanese society is essentially a vital urban society in which it is not really possible to en- visage the problem of “shrinking cities”—at least not yet. Even during Japan’s twelve-year recession, from which the country is only now beginning to recover, the cities seem too dynamic for that. Despite the fact that the economic situation has been precarious for so long, or perhaps precisely for that reason, the construction boom has continued unabated not only in the rural peripheries but in the large cities themselves. On the one hand, this seems surprising; on the other, it is understandable. The Japanese construction lobby, which is headed by power- ful players within the system of the so-called Iron Triangle (the interplay of ministerial burea- ucracy, politics, and business), have been able to push the expenditures on economic stimulus programs—that is, deficit spending—to dangerous levels on all geographic scales (national, regional, and local) and thus still guarantee the profit potential for theTriangle members through cartel-like bidder agreements (dango) in their own interest.1 Today’s Japan gives the impression that its planning for urban and regional development, energy, and transport is still based on predictions of growth. -

Arts Stability and Growth Amid Redevelopment in US Shrinking Cities' Downtowns

Arts Stability and Growth amid Redevelopment in U.S. Shrinking Cities’ Downtowns: A Case Study Joanna Ganning, PhD Assistant Professor, Department of City & Metropolitan Planning Executive Director, Metropolitan Research Center University of Utah [email protected] 801-587-8129 (working paper) This project was supported in part or in whole by an award from the Research: Art Works program at the National Endowment for the Arts: Grant# 13-3800-7002. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Office of Research & Analysis or the National Endowment for the Arts. The NEA does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information included in this report and is not responsible for any consequence of its use. Arts Stability and Growth amid Redevelopment in U.S. Shrinking Cities’ Downtowns: A Case Study Keywords: arts, downtowns, redevelopment, shrinking cities Abstract: While the relationship of arts businesses and redevelopment has been studied extensively in world-class cities, it remains understudied in weaker market cities. With tight municipal budgets, shrinking cities cannot afford not to understand both the benefits of the arts for downtown redevelopment, and the impact of redevelopment on the arts. Using block-level data for a United States shrinking city’s downtown (St. Louis), this paper finds that the arts have neither anchored redevelopment nor been driven out of the downtown by redevelopment. The latter finding signals an opportunity for shrinking cities to harness the benefits of the arts in downtown redevelopment. Introduction The idea that arts and artists play a critical role in transforming blighted neighborhoods into hip enclaves is well established in the literature (e.g., Currid, 2009; Lloyd, 2002). -

Historic Eastside/Springfield

Historic Eastside/Springfield Community Quality-of-Life Plan Planning Task Force: Individuals Helen Albee • Jennifer Anderson • Rickey Anderson & Guest • Michael Arbery • Shawn Ashley • April Atkins • Valerie Baham • Shakera Bailey • Nevesha Baker • Casey Barnum • Lester Bass • Lucille Battle • Annie Bean • Quinn Bell • Larry Bennett • Claudia Bentford • Jerry F. Box • Brenda Boydston • Michelle Braun • Bill Brinton • John Brooken • Tina Brooks • Justin Brown • Mickee Brown • Niki Brunson • J.F. Br yan • Co’Relous Bryant • Catherine Burkee • Richard Burnett • David Byres • Leigh Cain • Bishop Terrance Calloway • Jim Capraro • Kathleen Carignan • Katy Carigno • Wilmot Carson • Mike Cochran • Michelle Cooper • Ken Covington • Lauren Cowman • Christina Crews • Chris Cunninghan • Evan Daniels • Melissa Davis • Rose Devoe • Ty Dixon • Farand Dockett • Fran Downing • Lloyd Downing • Jacqueline Dunbar • Cathy DuPont • Vincent Edmonds • Chistina Edwards • John Fabiano • Christine Farley • Donnie Ferguson • LaTanya Ferguson • Ronnie Ferguson • Jewel Flornoy • Robert Flornoy • Geraldine Ford-Hardine • Terri Foreman • Jeff Fountain • Dr. Johnny Gaffney • Jeff Gardner • Jolee Gardner • Felicia Garrison • Kevin T. Gay • Audrey Gibson • Marion Graham • Carl Green • Kendalyn Green • Michael Hancox • Florence Handen • Al Hardin • Jacqueline Harrington • Greta Harris • Marilyn Hauser • Robert Hauser • Nathaniel Hendley • William Hoff • Bryant Holley • Joseph Howard • Taffie Hubbard • Michelle Hughes • Liz Hubbard • Samuel Hunt • Riyan Jackson • Derek Jayson • Valerie Jenkins • Carlos Johnson • Ebony Johnson • Linda Johnson • Shanita Johnson • Theresa Johnson • Faye Johnson • Joann Jones • Wayshawn Kay Jefferson • Tia Keitt • Alice Kimbrough • Riva Kimbrough • Dave Knadler • Gary Kresel • Karen Landry • Clinton Lane • Jackie Lattimore • Lucius Lattimore • Laura Lavenia • Bobby Lee • Alisha Lewis • Crystal Lewis • Jackie Littlebee • Reginald Lott • Janice R. Love • Earline Lowe • Bob Lyle • Lane Manis • Steve Manis • Monica Martin • Sabrena McCullough • Marc A. -

Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too?

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES IS URBAN DECAY BAD? IS URBAN REVITALIZATION BAD TOO? Jacob L. Vigdor Working Paper 12955 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12955 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2007 The author is grateful to Yongsuk Lee, Joshua Kinsler and Patrick Dudley for research assistance, and to Erzo F.P. Luttmer and seminar participants at Yale University, the 2006 NBER Summer Institute workshop on Public Economics and Real Estate, and at the 2005 American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association International Meeting for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Remaining errors are the author's responsibility. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Jacob L. Vigdor. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too? Jacob L. Vigdor NBER Working Paper No. 12955 March 2007 JEL No. D1,R21,R31 ABSTRACT Many observers argue that urban revitalization harms the poor, primarily by raising rents. Others argue that urban decline harms the poor by reducing job opportunities, the quality of local public services, and other neighborhood amenities. While both decay and revitalization can have negative effects if moving costs are sufficiently high, in general the impact of neighborhood change on utility depends on the strength of price responses to neighborhood quality changes. Data from the American Housing Survey are used to estimate a discrete choice model identifying households' willingness-to-pay for neighborhood quality.