Funding Strategies and Project Costs for State-Supported Intercity Passenger Rail: Selected Case Studies and Cost Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Chapter (PDF)

CONTENTS Introduction by Fawn Μ. Brodie Note on the Text ROUTE FROM LIVERPOOL το GREAT SALT LAKE VALLEY Preface [Chapters I-IX by Linforth] Chapter I. Commencement of the Latter-day Saints' Emigration—History until the Suspension in 1846 Chapter II. Memorial to the Queen—Re-opening of the Emigration—History until 1851 Chapter III. History of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund—Act of Incorporation by the General Assembly of Deseret Chapter IV. History of the Emigration from 1851 to 1852—Contemplated Routes via the Isthmus of Panama and Cape Horn Chapter V. History of the Emigration from 1852 to April, 1854—Extensive Operations of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company vi CONTENTS Chapter VI. Foreign Emigration passing through Liverpool 38 Chapter VII. Statistics of the Latter-day Saints' Emigration from the British Isles 40 Chapter VIII. Mode of conducting the Emigration 49 Chapter IX. Instructions to Emigrants 54 [Chapters X-XXI by Piercy] Chapter X. Departure from Liverpool—San Domingo—Cuba—The Gulf of Mexico—The Mississippi River—The Balize—Arrival at New Orleans—Attempts of "Sharpers" to board the Ship and pilfer from the Emigrants 62 Chapter XI. Louisiana—The City of New Orleans—Disembarkation 71 Chapter XII. Departure from New Orleans—Steam-Boats—Negro-Slavery— Carrollton—The Face of the Country—-Baton Rouge—Red River —Mississippi—Unwholesomeness of the waters of the Mississippi —Danger in procuring Water from the Stream—Washing away of the Banks of the River—Snags—Landing at Natchez at night —Beautiful effect caused by reflection on the Water of the Light from the Steamboat Windows—^American Taverns and Hospi- tality—Rapidity at Meals—American Cooking Stoves and Wash- ing Boards—Old Fort Rosalie—An Amateur Artist 73 Chapter XIII. -

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

Harrisburg Line Capacity Improvements Upgrade of Track 2 from Glen Interlocking to Thorn Interlocking

HARRISBURG LINE CAPACITY IMPROVEMENTS UPGRADE OF TRACK 2 FROM GLEN INTERLOCKING TO THORN INTERLOCKING FEDERAL RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION FEDERAL-STATE PARTNERSHIP FOR STATE OF GOOD REPAIR PROGRAM GRANT APPLICATION Lead Applicant: Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) Joint Applicant: Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) FEDERAL FUNDING REQUESTED: $8,337,500 (50%) PROPOSED NON-FEDERAL MATCH: $8,337,500 (50%) TOTAL PROJECT COST: $16,675,000 PROJECT LOCATION: Caln Township, Downingtown Borough, East Caln Township, West Whiteland Township, & East Whiteland Township in Chester County, Pennsylvania - 6th Congressional District No Federal Grant Application Previously Submitted for this Project Table of Contents I. Project Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Project Funding ..................................................................................................................................... 2 III. Applicant Eligibility ............................................................................................................................... 3 IV. NEC Project Eligibility ........................................................................................................................... 3 V. Detailed Project Description ................................................................................................................ 5 VI. Project Location ................................................................................................................................. -

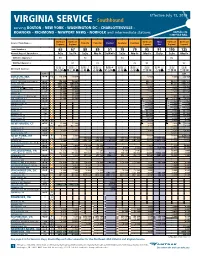

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

November 2008–January 2009 Coast D.C

POSITIVE TRAIN CONTROL BY 2015 PAGE 6 Volume 21 Number 1 Sacramento, CA January 2009 Voters Want Rail Progress DEMO PLAN Erases FUndinG GAINS In November, California voters elected CalRail 2020 attendees on November 9 a President who is ostensibly pro-Amtrak, tour of Siemens light rail and subway passed a state ballot initiative calling car fabrication plant in Sacramento. INSIDE for $10 billion to be spent on high speed Photo © by Randell Hansen and regional rail, and passed numerous PAGE 2 local rail funding measures including Los might save the day for California rail is Angeles County’s Measure R half-cent looking increasingly unlikely. BALLOT UPDATE sales tax. There is no doubt that voters Early signals from the Obama camp, want progress on rail. including his nominee for Transportation Passengers who have seen trains fill secretary Rep. Ray LaHood (R-IL), are PAGE 3 to capacity on Metrolink, Pacific Surfliner, that projects involving significant manual Capitol Corridor, and San Joaquin routes labor may have more appeal than ones COAST are impatient for progress on arrival of involving lengthy engineering, design, new cars. Voters who supported the rail and construction. In other words, track OB SERVATIONS measures because of claimed economic upgrades and highway paving projects benefits and job creation want to see are likely to trump high speed rail or new the projects start moving. Up until a few freeways because the facilities physically PAGE 4-5 weeks ago, activists were sanguine about exist and can be worked on immediately. new expansions of rail service. The new President has sought to HIG H SPEED PLAN Now, the worldwide economic cri- discourage expectations that new public sis, the budget-busting grants of billions works projects would be standard pork. -

Love of Ann Rutledge Led Agreement Reachedltoday

Pumping Machinery ^ 1 1-2 to 11 h. p. Fairbanks Centrifugal Pumps. 4^^ Morse and Atlas ^ Kreuger M ‘^L ^ A W.HMW.J ItjHF /Till -^^6^ /VWW^r ■ glL. ■■—■■- .. _:.. -—..-^__^=ir^„ —-=-i:--=tttt— ,-t ■' ■ .. FEBRUARY rOL. XXXIII No. 223 ESTABLISHED 1892 BROWNSVILLE, TEXAS, FRIDAY, 12, 1926 / EIGHT PAGES TODAY FIVE CENTS A COPY fife.... ---.---___ ■ .. ^ -r-■ .. .. OUR VALLEY *-----: fcPPY south winds have been blow- AUTO FRIGHTENS BABY over the Rio Grande ng Delta the * * * few days. MEXICO ORDERS Love of Ann Led RIVER DRAGGED a sign, as they say. Rutledge MAMA HURLS ins a change in the weather, ELEPHANT; * * * ibly will be followed by a brisk e out of the northwest shortly. TEN PRIESTS TO on FOR BOY I Observer Schnurbusch of the Lincoln to Greatness CAR INTO NEARBY DITCH BODY; d States Weather Bureau tells us somewhere up in northern Colo- (Bv The Associated in Wyoming there’s a disturb- Press.) Dutch East Feb. developing. LEAVE COUNTRY BATAVIA, Indies, TRIES * RESCUE 12.—How a mother rescued listurbance in that district at this elephant her which had been n of the year means weather for baby, frightened lection. by a small Amerrcar, automobile Others Held while the machine and hurled it Brother of Starr who can complain? Eight picked up County into a it to is ir weeks of wonderful weather, ravine, smashing bits, Goes Down Schols Are Instructed related in a here from Attorney een splendid. Gave the potato men story arriving Telok South Sumatra. ;>porunity to get their seed into To Vera Cruz Betong, In Effort to Swim Close; A before dawn round. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning Urban and Regional Planning January 2007 High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2 Allison deCerreno Shishir Mathur San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/urban_plan_pub Part of the Infrastructure Commons, Public Economics Commons, Public Policy Commons, Real Estate Commons, Transportation Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Allison deCerreno and Shishir Mathur. "High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2" Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning (2007). This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban and Regional Planning at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MTI Report 06-03 MTI HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS-PART 2 IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS-PART HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: Funded by U.S. Department of HIGH-SPEED RAIL Transportation and California Department PROJECTS IN THE UNITED of Transportation STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS PART 2 Report 06-03 Mineta Transportation November Institute Created by 2006 Congress in 1991 MTI REPORT 06-03 HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS PART 2 November 2006 Allison L. -

Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations

S. HRG. 111–983 Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations Departments of Transportation and Housing and Urban Development and Related Agencies Appropriations Fiscal Year 2011 111th CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION H.R. 5850/S. 3644 DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORPORATION (AMTRAK) NONDEPARTMENTAL WITNESSES WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSIT AUTHORITY Departments of Transportation and Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies Appropriations, 2011 (H.R. 5850/S. 3644) S. HRG. 111–983 TRANSPORTATION AND HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT, AND RELATED AGENCIES AP- PROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 5850/S. 3644 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR THE DEPARTMENTS OF TRANS- PORTATION AND HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT, AND RE- LATED AGENCIES FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2011, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Department of Housing and Urban Development Department of Transportation National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) Nondepartmental witnesses Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 54–989 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. -

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi M.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2011 B.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2009 Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2016 © 2016 Tatsuya Doi. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________________ Institute for Data, Systems, and Society May 6, 2016 Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Joseph M. Sussman JR East Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Olivier L. de Weck Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: _________________________________________________________________________ John N. Tsitsiklis Clarence J. Lebel Professor of Electrical Engineering IDSS Graduate Officer 1 2 Interaction of Lifecycle Properties In High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society on May 6, 2016 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems ABSTRACT High-Speed Rail (HSR) has been expanding throughout the world, providing various nations with alternative solutions for the infrastructure design of intercity passenger travel. HSR is a capital-intensive infrastructure, in which multiple subsystems are closely integrated. Also, HSR operation lasts for a long period, and its performance indicators are continuously altered by incremental updates. -

Passenger Rail System

Minnesota Comprehensive Statewide Freight and Passenger Rail Plan Passenger Rail System draft technical memorandum 3 prepared for Minnesota Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. with Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. TKDA, Inc. July 17, 2009 www.camsys.com technical memorandum 3 Minnesota Comprehensive Statewide Freight and Passenger Rail Plan Passenger Rail System prepared for Minnesota Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 100 CambridgePark Drive, Suite 400 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140 July 17, 2009 Minnesota Comprehensive Statewide Freight and Passenger Rail Plan Passenger Rail System Technical Memorandum Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ES-1 1.0 Objective ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 2.0 Methodology ................................................................................................................. 2-1 3.0 Overview of Findings .................................................................................................. 3-1 4.0 Operating and Capacity Conditions and Existing Ridership Forecasts for Potential Passenger Rail Corridors ........................................................................... 4-1 4.1 CP: Rochester-Winona......................................................................................... 4-1 4.2 CP: St. Paul-Red -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A.