Frans Hals in America: Another Embarrassment of Riches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plekken Van Plezier

Plekken van plezier Open Monumentendagen 14 & 15 september Haarlem - 1 Welkom in Haarlem Op de voorkant van dit programmaboekje prijkt zwembad De Houtvaart. Een prachtige plek van plezier in onze monumentenstad Haarlem. Dit jaar staat dan ook de amusementswaarde van monumenten centraal tijdens Open Monumentendagen, met als thema ‘Plekken van plezier’. Naar welke monumentale plekken gingen en gaan mensen voor hun plezier? Ik vind het belangrijk dat onze monumenten bewaard en beschermd blijven. Dat ze bezocht en bewonderd kunnen worden en dat ze ons leren wie we zijn en waar we vandaan komen. Veel vrijwilligers werken actief mee aan de organisatie en uitvoering van de Open Monumentendagen; vanaf deze plek wil ik iedereen hartelijk bedanken voor hun inzet. In dit boekje vindt u informatie over bijzondere monumenten in Haarlem die hun deuren voor u openen. Een mooie selectie van monumenten voor ontspanning, vermaak en vrije tijd. Ik wens u een plezierig weekend vol verrassende ervaringen toe! Floor Roduner, wethouder Monumenten en Erfgoed - 2 Plekken van plezier Hoe hebben mensen zich in de loop der eeuwen vermaakt en welke monumenten zijn daarvoor het decor of het podium geweest? Deze vragen zijn leidend geweest bij het samenstellen van dit programma boekje. In Haarlem zijn volop historische ‘plekken van plezier’ te vinden zoals theaters, musea, parken, markten en sportclubs. Al in de middeleeuwen zijn er plekken in Haarlem aan te wijzen die centraal staan voor vermaak. Zo had Haarlem als eerste stad ter wereld een heus sportveld, de ‘Baen’. Hier werden vanaf de 14de eeuw Oudhollandse spellen gespeeld. Een andere bekende plek van plezier is de Haarlemmerhout, een immense groene oase aan de zuidkant van de stad. -

Hermitage Magazine 27 En.Pdf

VIENNA / ART DECO / REMBRANDT / THE LANGOBARDS / DYNASTIC RULE VIENNA ¶ ART DECO ¶ THE LEIDEN COLLECTION ¶ REMBRANDT ¶ issue № 27 (XXVII) THE LANGOBARDS ¶ FURNITURE ¶ BOOKS ¶ DYNASTIC RULE MAGAZINE HERMITAGE The advertising The WORLD . Fragment 6/7 CLOTHING TRUNKS OF THE MUSEUM WARDROBE 10/18 THE INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD OF THE STATE HERMITAGE Game of Bowls 20/29 EXHIBITIONS 30/34 OMAN IN THE HERMITAGE The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. № ГЭ 9154 The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. Henri Matisse. 27 (XXVII) Official partners of the magazine: DECEMBER 2018 HERMITAGE ISSUE № St. Petersburg State University MAGAZINE Tovstonogov Russian State Academic Bolshoi Drama Theatre The Hermitage Museum XXI Century Foundation would like to thank the project “New Holland: Cultural Urbanization”, Aleksandra Rytova (Stella Art Foundation, Moscow) for the attention and friendly support of the magazine. FOUNDER: THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM Special thanks to Svetlana Adaksina, Marina Antipova, Elena Getmanskaya, Alexander Dydykin, Larisa Korabelnikova, Ekaterina Sirakonyan, Vyacheslav Fedorov, Maria Khaltunen, Marina Tsiguleva (The State Hermitage Museum); CHAIRMAN OF THE EDITORIAL BOARD Swetlana Datsenko (The Exhibition Centre “Hermitage Amsterdam”) Mikhail Piotrovsky The project is realized by the means of the grant of the city of St. Petersburg EDITORIAL: AUTHORS Editor-in-Chief Zorina Myskova Executive editor Vladislav Bachurov STAFF OF THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM: Editor of the English version Simon Patterson Mikhail Piotrovsky -

Sztuki Piękne)

Sebastian Borowicz Rozdział VII W stronę realizmu – wiek XVII (sztuki piękne) „Nikt bardziej nie upodabnia się do szaleńca niż pijany”1079. „Mistrzami malarstwa są ci, którzy najbardziej zbliżają się do życia”1080. Wizualna sekcja starości Wiek XVII to czas rozkwitu nowej, realistycznej sztuki, opartej już nie tyle na perspektywie albertiańskiej, ile kepleriańskiej1081; to również okres malarskiej „sekcji” starości. Nigdy wcześniej i nigdy później w historii europejskiego malarstwa, wyobrażenia starych kobiet nie były tak liczne i tak różnicowane: od portretu realistycznego1082 1079 „NIL. SIMILIVS. INSANO. QVAM. EBRIVS” – inskrypcja umieszczona na kartuszu, w górnej części obrazu Jacoba Jordaensa Król pije, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 1080 Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618), poeta niderlandzki. Cyt. za: W. Łysiak, Malarstwo białego człowieka, t. 4, Warszawa 2010, s. 353 (tłum. nieco zmienione). 1081 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing – Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1993; J. Friday, Photography and the Representation of Vision, „The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” 59:4 (2001), s. 351–362. 1082 Np. barokowy portret trumienny. Zob. także: Rembrandt, Modląca się staruszka lub Matka malarza (1630), Residenzgalerie, Salzburg; Abraham Bloemaert, Głowa starej kobiety (1632), kolekcja prywatna; Michiel Sweerts, Głowa starej kobiety (1654), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Monogramista IS, Stara kobieta (1651), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 314 Sebastian Borowicz po wyobrażenia alegoryczne1083, postacie biblijne1084, mitologiczne1085 czy sceny rodzajowe1086; od obrazów o charakterze historycznodokumentacyjnym po wyobrażenia należące do sfery historii idei1087, wpisujące się zarówno w pozy tywne1088, jak i negatywne klisze kulturowe; począwszy od Prorokini Anny Rembrandta, przez portrety ubogich staruszek1089, nobliwe portrety zamoż nych, starych kobiet1090, obrazy kobiet zanurzonych w lekturze filozoficznej1091 1083 Bernardo Strozzi, Stara kobieta przed lustrem lub Stara zalotnica (1615), Музей изобразительных искусств им. -

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of Semester

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of semester Rosenberg, Jakob and Slive, Seymour . Chapter 4: Frans Hals . Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600-1800 . Rosenberg, Jakob, Slive, S.and ter Kuile, E.H. p. 30-47 . Middlesex, England; Baltimore, MD . Penguin Books . 1966, 1972 . Call Number: ND636.R6 1966 . ISBN: . The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or electronic reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or electronic reproduction of copyrighted materials that is to be "used for...private study, scholarship, or research." You may download one copy of such material for your own personal, noncommercial use provided you do not alter or remove any copyright, author attribution, and/or other proprietary notice. Use of this material other than stated above may constitute copyright infringement. http://library.umbc.edu/reserves/staff/bibsheet.php?courseID=5869&reserveID=16583[8/18/2016 12:48:14 PM] f t FRANS HALS: EARLY WORKS 1610-1620 '1;i no. l6II, destroyed in the Second World War; Plate 76n) is now generally accepted 1 as one of Hals' earliest known works. 1 Ifit was really painted by Hals - and it is difficult CHAPTER 4 to name another Dutch artist who used sucli juicy paint and fluent brushwork around li this time - it suggests that at the beginning of his career Hals painted pictures related FRANS HALS i to Van Mander's genre scenes (The Kennis, 1600, Leningrad, Hermitage; Plate 4n) ~ and late religious paintings (Dance round the Golden Calf, 1602, Haarlem, Frans Hals ·1 Early Works: 1610-1620 Museum), as well as pictures of the Prodigal Son by David Vinckboons. -

Vermeer in the Age of the Digital Reproduction and Virtual

VERMEER IN THE AGE OF THE DIGITAL REPRODUCTION AND VIRTUAL COMMUNICATION MIRIAM DE PAIVA VIEIRA Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais ABSTRACT: The twentieth century was responsible for the revival of the visual arts, lending techniques to literature, in particular, after the advent of cinema. This visual revival is illustrated by the intersemiotic translations of Girl with a Pearl Earring: a recent low-budget movie was responsible for the revival of ordinary public interest in an art masterpiece from the seventeenth century. However, it was the book about the portrait that catalyzed this process of rejuvenation by verbalizing the portrait and inspiring the cinematographic adaptation, thereby creating the intersemiotic web. In this media-saturated environment we now live in, not only do books inspire movie adaptations, but movies inspire literary works; adaptations of screenplays are published; movies are adapted into musicals, television shows and even videogames. For James Naremore, every form of retelling should be added to the “study of adaptation in the age of the mechanical reproduction and electronic communication” (NAREMORE, 2000: 12-15), long previewed in Walter Benjamin’s milestone article (1936). Nowadays, the celebrated expression could be changed to the age of the digital reproduction and virtual communication, since new technologies and the use of new media have been changing the relations between, and within, the arts. The objective of this essay is to explore Vermeer’s influence on contemporary art and media production, with focus on the collection of portraits from the book entitled Domestic Landscapes (2007) by the Dutch photographer Bert Teunissen, confirming the study of recycling within a general theory of repetition proposed by James Naremore, under the light of intermediality. -

Some Pages from the Book

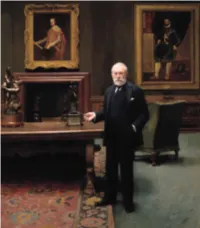

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

To Emile Bernard. Arles, Monday, 30 July 1888

To Emile Bernard. Arles, Monday, 30 July 1888. Monday, 30 July 1888 Metadata Source status: Original manuscript Location: New York, Thaw Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum Date: Assuming that Van Gogh honoured his promise to write again soon, the present letter dates from shortly after the previous one to Bernard (letter 649, of 29 July). The opening words accordingly appear to be an immediate continuation of their discussion about painting, while the drawings that Bernard had sent are examined at the end. Van Goghs new model, Joseph Roulin, who posed for him on 31 July, is not mentioned, despite the fact that the importance of painting portraits is stressed in this letter. On the assumption that he would have told Bernard about Roulins portrait if he had already painted it, as he did Theo and Willemien in letters 652 and 653, both of 31 July, we have dated this letter Monday, 30 July 1888. Additional: Original [1r:1] Mon cher copain Bernard. Tu admettras, jen doute aucunement, que ni toi ni moi ne puissions avoir de Velasquez et de Goya une ide complte de ce quils etaient comme homme et comme peintres, car ni toi ni moi navons vu lEspagne, leur pays et tant de belles choses qui sont restes dans le midi. Nempche que ce que lon en connait cest dj quelque chse. 1 Va sans dire que pour les gens du nord, Rembrandt en tte, il est excessivement dsirable de connatre, en jugeant ces peintres, et leur oeuvre dans toute son tendue, et leur pays et lhistoire un peu intime et serre de lpoque et des moeurs de lantique pays. -

JAARVERSLAG 2018 Cover Frans Hals, Portret Van Een Dame Met Handschoenen, C

FRANS HALS MUSEUM JAARVERSLAG 2018 Cover Frans Hals, Portret van een dame met handschoenen, c. 1645/50 (foto: Arend Velsink) Koos Breukel, Cosmetic View (Gwennie), 2005 Grote Markt 16 Groot Heiligland 62 2011 RD Haarlem 2011 ES Haarlem Postbus 3365, 2001 DJ Haarlem [email protected] www.franshalsmuseum.nl 2 INHOUDS OPGAVE INHOUDS OPGAVE 3 VERLIEFD, VERLOOFD, GETROUWD EN HET EERSTE KROOST 5 BERICHT VAN DE RAAD VAN TOEZICHT 7 TENTOON STELLINGEN 11 PUBLICATIES 20 COLLECTIES 22 Aankopen 23 Schenkingen 23 Bruiklenen 24 Restauraties 24 Registraties en inventarisaties 24 ONDERZOEK FRANS HALS 25 Onderzoeksprojecten 25 Frans Hals kenniscentrum 25 Bijeenkomsten 25 PUBLIEKS ZAKEN 26 Marketing en PR 26 Communicatie 28 Publieksonderzoek 30 Educatie en publiek 30 Publieksactiviteiten 33 FONDSENWERVING EN RELATIEBEHEER 38 Fondsen 38 BankGiro Loterij 39 Particulieren en relatiebeheer 40 Sponsoring 40 3 PERSONEEL EN ORGANISATIE 41 Organogram 41 Bezetting 42 Bedrijfsvoering 44 Samenwerkingsverbanden 44 GOVERNANCE 46 Governance Code Cultuur 46 Raad van Toezicht 46 Auditcommissie 47 Raad van Advies 47 VERENIGING VAN VRIENDEN VAN HET FRANS HALS MUSEUM 48 TOELICHTING BIJ DE SAMENGEVATTE JAARREKENING 50 FINANCIEEL VERSLAG 51 Exploitatierekening 2018 53 Toelichting besteding gelden BankGiro Loterij 54 Toelichting Wet Normering Topinkomens 55 4 VERLIEFD, VERLOOFD, GETROUWD EN HET EERSTE KROOST Beste lezer, Amsterdam maakt er een prachtige interactieve online vertaling van. De nieuwe website, die vervolgens veel Daar zitten ze dan op de bank, Hof en Hal, het pasge- nominaties krijgt, is het digitale visitekaartje van het trouwde stel. Aan het bijkomen van hun eerste huwe- museum. lijksjaar. Een beetje beduusd door de veranderingen die het getrouwde leven met zich meebrengt, maar Ruim twee weken voor de bruiloft vindt in De Hallen ook intens tevreden over het vruchtbare samenzijn. -

"MAN with a BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED to FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION and SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian

Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies Fogg Art Museum Harvard University 1'1 Ii I "MAN WITH A BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED TO FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION AND SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian July 1984 ___~.~J INDEX Abst act 3 In oduction 4 ans Hals, his school and circle 6 Writings of Carel van Mander Technical examination: A. visual examination 11 B ultra-violet 14 C infra-red 15 D IR-reflectography 15 E painting materials 16 F interpretatio of the X-radiograph 25 G remarks 28 Painting technique in the 17th c 29 Painting technique of the "Man with a Beer Keg" 30 General Observations 34 Comparison to other paintings by Hals 36 Cone usions 39 Appendix 40 Acknowl ement 41 Notes and References 42 Bibliog aphy 51 ---~ I ABSTRACT The "Man with a Beer Keg" attributed to Frans Hals came to the Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies for technical examination, pigment analysis and restoration. A series of samples was taken and cross-sections were prepared. The pigments and the binding medium were identified and compared to the materials readily available in 17th century Holland. Black and white, infra-red and ultra-violet photographs as well as X-radiographs were taken and are discussed. The results of this study were compared to 17th c. materials and techniques and to the literature. 3 INTRODUCTION The "Man with a Beer Keg" (oil on canvas 83cm x 66cm), painted around 1630 - 1633) appears in the literature in 1932. [1] It was discovered in London in 1930. It had been in private hands and was, at the time, celebrated as an example of an unsuspected and startling find of an old master. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

Walk Among Teyler and Hals

Verspronckweg Schotersingel Kloppersingel Staten Bolwerk Kennemerplein Rozenstraat Prinsen Bolwerk Kenaustraat Stationsplein singel Parkeergarage Stationsplein Garenkookerskade Kenaupark Kinderhuis Parklaan Parklaan Parklaan Kruisweg Jansweg Parklaan Hooimarkt Spaarne Nieuwe Gracht Nieuwe Gracht Nassaustraat Zijlweg Kinderhuissingel Kinderhuisvest Ridderstraat BakenessergrachtBakenessergracht Koudenhorn Kruisstraat Molen De Adriaan Grote or St. Bavokerk (20, St Bavo’s Church) was built in Gothic Walk left of the town hall into Koningstraat. Halfway down this street, on your Jansstraat 22 Nassaulaan style in the spot where a smaller church, which was largely destroyed in right, you can see the former school for Catholic girls, ‘Inrichting voor Onderwijs Route 1 - Starting point: Frans Hals Museum Route map WALK AMONG a fire in the 14th century, once stood. St Bavo is the patron saint of the aan Katholieke Meisjes’ and then on your left at No. 37, the asymmetrically shaped Zijlstraat Papentorenvest Route 2 - Starting point: Teylers Museum Smedestraat TEYLER AND HALS Kennemerland region. In 1479, the building was rebuilt as a collegiate church. former bakery (24) in Berlage style (1900). Decorative Jugendstil carvings by Brouwersvaart The remarkable thing about this church is that it was built without piles in G. Veldheer embellish both sides of the freestone façade frame. The figure of a Bakenessergracht the ground. Grote or St. Bavokerk is sometimes also referred to as ‘Jan met baker is depicted in the keystone above the shop window. Gedempte Oude Gracht Zijlstraat Raaks 15 de hoge schouders’ (high-shouldered John) because the tower is rather small Barteljorisstraat compared to the rest of the building. The church houses the tombs of Frans At the end of Koningstraat, cross Gedempte Oude Gracht and continue straight on Grote 16 Parkeer- Drossestraat 23 19 Hals, Pieter Teyler Van der Hulst and Pieter Jansz. -

Mijn Rembrandt

VAN DE MAKERS VAN HET NIEUWE RIJKSMUSEUM DISCOURS FILM PRESENTEERT MIJN REMBRANDT EEN FILM VAN OEKE HOOGENDIJK PERSMAP MIJN REMBRANDT NEDERLAND | 95 MINUTEN | KLEUR EEN PRODUCTIE VAN Discours Film Oeke Hoogendijk & Frank van den Engel MET STEUN VAN Nederlands Filmfonds Production Incentive AFK Fonds 21 VSB Fonds PRODUCENT Discours Film Oeke Hoogendijk, Frank van den Engel +31(0)6 51 17 00 99 [email protected] DISTRIBUTEUR BENELUX Cinéart Nederland B.V. T +31(0)20 5308848 www.cineart.nl PERS Julia van Berlo M: +31 (0)6 83785238 T: +31 (0)20 5308840 [email protected] SALES & DISTRIBUTIE Cinephil – Philippa Kowarsky Cinephil.com [email protected] MIJN REMBRANDT PERSMAP 2 MIJN REMBRANDT LOGLINE Rembrandt houdt, 350 jaar na zijn dood, de kunst- wereld nog altijd in zijn greep. De epische documen- taire MIJN REMBRANDT duikt in de exclusieve wereld van Rembrandtbezitters en Rembrandtjagers, waar men gedreven wordt door bewondering, hoogmoed, geld en afgunst, maar bovenal door een grenzeloze passie en liefde voor het werk van de grootmeester van de intimiteit. MIJN REMBRANDT PERSMAP 3 SYNOPSIS MIJN REMBRANDT speelt zich af in de wereld van de oude meesters en biedt een mozaïek van aangrijpende verhalen, waarin de grenzeloze passie voor Rembrandts schilderijen leidt tot dramatische ontwik- kelingen en verrassende plotwendingen. Terwijl collectioneurs zoals het echtpaar De Mol van Otterloo, de Amerikaan Thomas Kaplan en de Schotse hertog van Buccleuch, ons deelgenoot maken van hun speciale band met ‘hun’ Rembrandt, brengt de Franse baron Eric de Rothschild twee Rembrandts op de markt. Dit is het begin van een verbeten politieke strijd tussen het Rijksmuseum en het Louvre.