Arxiv:1806.02345V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 18 Feb 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

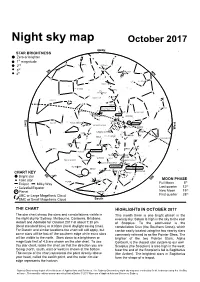

15Th October at 19:00 Hours Or 7Pm AEST

TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 URSA MINOR CEPHEUS CASSIOPEIA DRACO Night sky map OctoberDRACO 2017 URSA MAJOR North North STAR BRIGHTNESS Zero or brighter 1st magnitude nd LACERTA Deneb 2 NE rd NE Vega CYGNUS CANES VENATICI LYRAANDROMEDA 3 Vega NW th NW 4 LYRA LEO MINOR CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES VULPECULA COMA BERENICES Arcturus PEGASUS SAGITTA DELPHINUS SAGITTA SERPENS LEO Altair EQUULEUS PISCES Regulus AQUILAVIRGO Altair OPHIUCHUS First Quarter Moon SERPENS on the 28th Spica AQUARIUS LIBRA Zubenelgenubi SCUTUM OPHIUCHUS CORVUS Teapot SEXTANS SERPENS CAPRICORNUS SERPENSCRATER AQUILA SCUTUM East East Antares SAGITTARIUS CETUS PISCIS AUSTRINUS P SATURN Centre of the Galaxy MICROSCOPIUM Centre of the Galaxy HYDRA West SCORPIUS West LUPUS SAGITTARIUS SCULPTOR CORONA AUSTRALIS Antares GRUS CENTAURUS LIBRA SCORPIUS NORMAINDUS TELESCOPIUM CORONA AUSTRALIS ANTLIA Zubenelgenubi ARA CIRCINUS Hadar Alpha Centauri PHOENIX Mimosa CRUX ARA CAPRICORNUS TRIANGULUM AUSTRALEPAVO PYXIS TELESCOPIUM NORMAVELALUPUS FORNAX TUCANA MUSCA 47 Tucanae MICROSCOPIUM Achernar APUS ERIDANUS PAVO SMC TRIANGULUM AUSTRALE CIRCINUS OCTANSCHAMAELEON APUS CARINA HOROLOGIUMINDUS HYDRUS Alpha Centauri OCTANS SouthSouth CelestialCelestial PolePole VOLANS Hadar PUPPIS RETICULUM POINTERS SOUTHERN CROSS PISCIS AUSTRINUS MENSA CHAMAELEONMENSA MUSCA CENTAURUS Adhara CANIS MAJOR CHART KEY LMC Mimosa SE GRUS DORADO SMC CAELUM LMCCRUX Canopus Bright star HYDRUS TUCANA SWSW MOON PHASE Faint star VOLANS DORADO -

Instruction Manual

1 Contents 1. Constellation Watch Cosmo Sign.................................................. 4 2. Constellation Display of Entire Sky at 35° North Latitude ........ 5 3. Features ........................................................................................... 6 4. Setting the Time and Constellation Dial....................................... 8 5. Concerning the Constellation Dial Display ................................ 11 6. Abbreviations of Constellations and their Full Spellings.......... 12 7. Nebulae and Star Clusters on the Constellation Dial in Light Green.... 15 8. Diagram of the Constellation Dial............................................... 16 9. Precautions .................................................................................... 18 10. Specifications................................................................................. 24 3 1. Constellation Watch Cosmo Sign 2. Constellation Display of Entire Sky at 35° The Constellation Watch Cosmo Sign is a precisely designed analog quartz watch that North Latitude displays not only the current time but also the correct positions of the constellations as Right ascension scale Ecliptic Celestial equator they move across the celestial sphere. The Cosmo Sign Constellation Watch gives the Date scale -18° horizontal D azimuth and altitude of the major fixed stars, nebulae and star clusters, displays local i c r e o Constellation dial setting c n t s ( sidereal time, stellar spectral type, pole star hour angle, the hours for astronomical i o N t e n o l l r f -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

The Constellation Microscopium, the Microscope Microscopium Is A

The Constellation Microscopium, the Microscope Microscopium is a small constellation in the southern sky, defined in the 18th century by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in 1751–52 . Its name is Latin for microscope; it was invented by Lacaille to commemorate the compound microscope, i.e. one that uses more than one lens. The first microscope was invented by the two brothers, Hans and Zacharius Jensen, Dutch spectacle makers of Holland in 1590, who were also involved in the invention of the telescope (see below). Lacaille first showed it on his map of 1756 under the name le Microscope but Latinized this to Microscopium on the second edition published in 1763. He described it as consisting of "a tube above a square box". It contains sixty-nine stars, varying in magnitude from 4.8 to 7, the lucida being Gamma Microscopii of apparent magnitude 4.68. Two star systems have been found to have planets, while another has a debris disk. The stars that now comprise Microscopium may formerly have belonged to the hind feet of Sagittarius. However, this is uncertain as, while its stars seem to be referred to by Al-Sufi as having been seen by Ptolemy, Al-Sufi does not specify their exact positions. Microscopium is bordered Capricornus to the north, Piscis Austrinus and Grus to the west, Sagittarius to the east, Indus to the south, and touching on Telescopium to the southeast. The recommended three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted Seen in the 1824 star chart set Urania's Mirror (lower left) by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is 'Mic'. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

Searching for Dark Matter Annihilation in Recently Discovered Milky Way Satellites with Fermi-Lat A

The Astrophysical Journal, 834:110 (15pp), 2017 January 10 doi:10.3847/1538-4357/834/2/110 © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. SEARCHING FOR DARK MATTER ANNIHILATION IN RECENTLY DISCOVERED MILKY WAY SATELLITES WITH FERMI-LAT A. Albert1, B. Anderson2,3, K. Bechtol4, A. Drlica-Wagner5, M. Meyer2,3, M. Sánchez-Conde2,3, L. Strigari6, M. Wood1, T. M. C. Abbott7, F. B. Abdalla8,9, A. Benoit-Lévy10,8,11, G. M. Bernstein12, R. A. Bernstein13, E. Bertin10,11, D. Brooks8, D. L. Burke14,15, A. Carnero Rosell16,17, M. Carrasco Kind18,19, J. Carretero20,21, M. Crocce20, C. E. Cunha14,C.B.D’Andrea22,23, L. N. da Costa16,17, S. Desai24,25, H. T. Diehl5, J. P. Dietrich24,25, P. Doel8, T. F. Eifler12,26, A. E. Evrard27,28, A. Fausti Neto16, D. A. Finley5, B. Flaugher5, P. Fosalba20, J. Frieman5,29, D. W. Gerdes28, D. A. Goldstein30,31, D. Gruen14,15, R. A. Gruendl18,19, K. Honscheid32,33, D. J. James7, S. Kent5, K. Kuehn34, N. Kuropatkin5, O. Lahav8,T.S.Li6, M. A. G. Maia16,17, M. March12, J. L. Marshall6, P. Martini32,35, C. J. Miller27,28, R. Miquel21,36, E. Neilsen5, B. Nord5, R. Ogando16,17, A. A. Plazas26, K. Reil15, A. K. Romer37, E. S. Rykoff14,15, E. Sanchez38, B. Santiago16,39, M. Schubnell28, I. Sevilla-Noarbe18,38, R. C. Smith7, M. Soares-Santos5, F. Sobreira16, E. Suchyta12, M. E. C. Swanson19, G. Tarle28, V. Vikram40, A. R. Walker7, and R. H. Wechsler14,15,41 (The Fermi-LAT and DES Collaborations) 1 Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA; [email protected], [email protected] 2 Department of Physics, Stockholm University, AlbaNova, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] 3 The Oskar Klein Centre for Cosmoparticle Physics, AlbaNova, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 4 Dept. -

Constellation Phoenix Product Overview Brochure Chariot of the Gods the True Core of Any Ship Is the Command Center

constellation Phoenix product overview brochure Chariot of the gods The true core of any ship is the command center. The Constel- lation Phoenix starts with a primary opera- tor seat designed by Gallo & Frost. UltraRez displays provide crystal clear display elements from a variety of per- spectives as well as efficient touchscreen interfaces. Want more? Every Constellation is prefit- ted for an expansion station — you can choose and purchase from our upcom- ing range of options, including command, exploration and enter- tainment. Triple crest dining Every meal will be a banquet on an Atuvo state table with a complete kitchen system at your beck and call. Experience haute cuisine like never before with the Phoenix’s top-of-the-line range of cooking appliances. A state of rest Every guest cabin is fitted with easily acces- sible storage compart- ments, a privacy screen and a contouring, anti- microbial mattress. Life, on your terms Constellation Phoenix is more than a luxury ship. The Phoenix is a vision of superior engineering for the modern age — maintaining all the functionality of the other Constellations, but optimized for those who refuse to accept anything less than perfection. A modern classic An atmosphere of tranquility and comfort awaits you and your guests in the spacious interiors designed by Emil Quast. A feast for the eyes The Constellation Phoenix transforms RSI’s award-winning hull into the luxury craft for the modern era and beyond. Your guests will enjoy the finest amenities while travelling in safety and security. A captain’s cabin Private and stately, the master suite features a sleeping system from Wintle Design Co. -

VOLANS-CARINA: a NEW 90 Myr OLD STELLAR ASSOCIATION at 85 Pc

Draft version August 15, 2018 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 VOLANS-CARINA: A NEW 90 Myr OLD STELLAR ASSOCIATION AT 85 pc Jonathan Gagne´,1, 2 Jacqueline K. Faherty,3 and Eric E. Mamajek4, 5 1Carnegie Institution of Washington DTM, 5241 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington, DC 20015, USA 2NASA Sagan Fellow 3Department of Astrophysics, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th St., New York, NY 10024, USA 4Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA 5Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14627, USA Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT We present a characterization of the new Volans-Carina Association (VCA) of stars near the Galactic plane (b ' -10°) at a distance of ' 75{100 pc, previously identified as group 30 by Oh et al.(2017). We compile a list of 19 likely members from Gaia DR2 with spectral types B8{M2, and 46 additional candidate members from Gaia DR2, 2MASS and AllWISE with spectral types A0{M9 that require +5 further follow-up for confirmation. We find an isochronal age of 89−7 Myr based on MIST isochrones calibrated with Pleiades members. This new association of stars is slightly younger than the Pleiades, with less members but located at a closer distance, making its members ' 3 times as bright than those of the Pleiades on average. It is located further than members of the AB Doradus moving group which have a similar age, but it is more compact on the sky which makes it less prone to contamination from random field interlopers. -

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves An AAVSO course for the Carolyn Hurless Online Institute for Continuing Education in Astronomy (CHOICE) This is copyrighted material meant only for official enrollees in this online course. Do not share this document with others. Please do not quote from it without prior permission from the AAVSO. Table of Contents Course Description and Requirements for Completion Chapter One- 1. Introduction . What are variable stars? . The first known variable stars 2. Variable Star Names . Constellation names . Greek letters (Bayer letters) . GCVS naming scheme . Other naming conventions . Naming variable star types 3. The Main Types of variability Extrinsic . Eclipsing . Rotating . Microlensing Intrinsic . Pulsating . Eruptive . Cataclysmic . X-Ray 4. The Variability Tree Chapter Two- 1. Rotating Variables . The Sun . BY Dra stars . RS CVn stars . Rotating ellipsoidal variables 2. Eclipsing Variables . EA . EB . EW . EP . Roche Lobes 1 Chapter Three- 1. Pulsating Variables . Classical Cepheids . Type II Cepheids . RV Tau stars . Delta Sct stars . RR Lyr stars . Miras . Semi-regular stars 2. Eruptive Variables . Young Stellar Objects . T Tau stars . FUOrs . EXOrs . UXOrs . UV Cet stars . Gamma Cas stars . S Dor stars . R CrB stars Chapter Four- 1. Cataclysmic Variables . Dwarf Novae . Novae . Recurrent Novae . Magnetic CVs . Symbiotic Variables . Supernovae 2. Other Variables . Gamma-Ray Bursters . Active Galactic Nuclei 2 Course Description and Requirements for Completion This course is an overview of the types of variable stars most commonly observed by AAVSO observers. We discuss the physical processes behind what makes each type variable and how this is demonstrated in their light curves. Variable star names and nomenclature are placed in a historical context to aid in understanding today’s classification scheme. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

Sydney Observatory Night Sky Map September 2012 a Map for Each Month of the Year, to Help You Learn About the Night Sky

Sydney Observatory night sky map September 2012 A map for each month of the year, to help you learn about the night sky www.sydneyobservatory.com This star chart shows the stars and constellations visible in the night sky for Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Adelaide and Perth for September 2012 at about 7:30 pm (local standard time). For Darwin and similar locations the chart will still apply, but some stars will be lost off the southern edge while extra stars will be visible to the north. Stars down to a brightness or magnitude limit of 4.5 are shown. To use this chart, rotate it so that the direction you are facing (north, south, east or west) is shown at the bottom. The centre of the chart represents the point directly above your head, called the zenith, and the outer circular edge represents the horizon. h t r No Star brightness Moon phase Last quarter: 08th Zero or brighter New Moon: 16th 1st magnitude LACERTA nd Deneb First quarter: 23rd 2 CYGNUS Full Moon: 30th rd N 3 E LYRA th Vega W 4 LYRA N CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES VULPECULA SAGITTA PEGASUS DELPHINUS Arcturus Altair EQUULEUS SERPENS AQUILA OPHIUCHUS SCUTUM PISCES Moon on 23rd SERPENS Zubeneschamali AQUARIUS CAPRICORNUS E SAGITTARIUS LIBRA a Saturn Centre of the Galaxy Antares Zubenelgenubi t s Antares VIRGO s t SAGITTARIUS P SCORPIUS P e PISCESMICROSCOPIUM AUSTRINUS SCORPIUS Mars Spica W PISCIS AUSTRINUS CORONA AUSTRALIS Fomalhaut Centre of the Galaxy TELESCOPIUM LUPUS ARA GRUSGRUS INDUS NORMA CORVUS INDUS CETUS SCULPTOR PAVO CIRCINUS CENTAURUS TRIANGULUM -

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, the FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) Is a Small Constellation in the Deep Southern Sky

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, THE FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) is a small constellation in the deep southern sky. It was one of twelve constellations created by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman and it first appeared on a 35-cm diameter celestial globe published in 1597 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603. It was also known as Apis (Latin: bee) for two hundred years. Musca remains below the horizon for most Northern Hemisphere observers. Also known as the Southern or Indian Fly, the French Mouche Australe ou Indienne, the German Südliche Fliege, and the Italian Mosca Australe, it lies partly in the Milky Way, south of Crux and east of the Chamaeleon. De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue in 1598 under the Dutch name De Vlieghe, ‘The Fly’ This title generally is supposed to have been substituted by La Caille, about 1752, for Bayer's Apis, the Bee; but Halley, in 1679, had called it Musca Apis; and even previous to him, Riccioli catalogued it as Apis seu Musca. Even in our day the idea of a Bee prevails, for Stieler's Planisphere of 1872 has Biene, and an alternative title in France is Abeille. When the Northern Fly was merged with Aries by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1929, Musca Australis was given its modern shortened name Musca. It is the only official constellation depicting an insect. Julius Schiller, who redrew and named all the 88 constellations united Musca with the Bird of Paradise and the Chamaeleon as mother Eve.