Proposals 2015-C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Wing Shape and Dispersal Analysis

Data Supplement High dispersal ability inhibits speciation in a continental radiation of passerine birds Santiago Claramunt, Elizabeth P. Derryberry, J. V. Remsen, Jr. & Robb T. Brumfield Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA HAND-WING INDEX AND FLIGHT PERFORMANCE IN NEOTROPICAL FOREST BIRDS We investigated the relationship between wing shape and flight distances determined during 'dispersal challenge' experiments conducted in Gatun Lake in the Panama Canal (Moore et al. 2008). During the experiments, birds were released from a boat at incremental distances from shore and the distance flown or the success or failure in reaching the coast was recorded. To investigated the relationship between the hand-wing index and flight distance in Neotropical birds we used data on mean distance flown from table 3 in ref. We estimated hand-wing indices for the 10 species reported in those experiments (Table S1) . Wing measurements were taken by SC for four males of each species at LSUMNS. The relationship between the hand-wing index and distance flown was evaluated statistically using phylogenetic generalized least-squares (PGLS, Freckleton et al. 2002). We generated a phylogeny for the species involved in the experiment or an appropriate surrogate using DNA sequences of the slow-evolving RAG 1 gene from GenBank (Table S2). A maximum likelihood ultrametric tree was generated in PAUP* (Swofford 2003) using a GTR+! model of nucleotide substitution rates, empirical nucleotide frequencies, and enforcing a molecular clock. We found that the hand-wing index was strongly related to mean distance flown (R2 = 0.68, F = 20, d.f. -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

Threatened Birds of the Americas

GREY-HEADED ANTBIRD Myrmeciza griseiceps E2 This rare formicariid is confined to patches of bamboo and dense undergrowth in semi-deciduous moist forest and cloud-forest in the Pacific slope foothills of the Andes in south-west Ecuador and north-west Peru, where it is threatened by habitat destruction. DISTRIBUTION The Grey-headed Antbird (see Remarks 1) is confined to the Pacific slope of the Andes in El Oro and Loja provinces, south-west Ecuador, and Tumbes and Piura departments, north-west Peru, where it is found at elevations ranging from 600 to 2,900 m. The bird is known from few specimens, and is generally distributed in five areas, where localities (coordinates from Paynter and Traylor 1977 and Stephens and Traylor 1983) are as follows: Ecuador (El Oro) La Chonta, 610 m (Chapman 1926, Zimmer 1932), at 3°35’S 79°53’W (see Remarks 2); San Pablo, 1,200 m, at 3°41’S 79°33’W, near Zaruma, where a bird (possibly this species) was heard calling in 1991 (Williams and Tobias 1991); (Loja) above Vicentino, 1,250-1,450 m, at c.3°56’S 79°55’W (five males singing in February 1991: Best 1992); Alamor, 1,400 m (Chapman 1926) at 4°02’S 80°02’W; Celica, 2,100 m (Zimmer 1932) at 4°07’S 79°59’W; 8 km west of Celica, 1,900 m (one specimen collected and others seen in August 1989: R. S. Ridgely in litt. 1989); near San José de Pozul along the road to Pindal, 1,600 m, at 4°07’S 80°03’W (sightings in April–May 1989: P. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

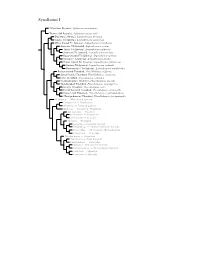

Synallaxini Species Tree

Synallaxini I ?Masafuera Rayadito, Aphrastura masafuerae Thorn-tailed Rayadito, Aphrastura spinicauda Des Murs’s Wiretail, Leptasthenura desmurii Tawny Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura yanacensis White-browed Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura xenothorax Araucaria Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura setaria Tufted Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura platensis Striolated Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striolata Rusty-crowned Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura pileata Streaked Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striata Brown-capped Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura fuliginiceps Andean Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura andicola Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura aegithaloides Rufous-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus rufifrons Streak-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticeps Little Thornbird, Phacellodomus sibilatrix Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Phacellodomus dorsalis Spot-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus maculipectus Greater Thornbird, Phacellodomus ruber Freckle-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticollis Orange-eyed Thornbird, Phacellodomus erythrophthalmus ?Orange-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus ferrugineigula Hellmayrea — White-tailed Spinetail Coryphistera — Brushrunner Anumbius — Firewood-gatherer Asthenes — Canasteros, Thistletails Acrobatornis — Graveteiro Metopothrix — Plushcrown Xenerpestes — Graytails Siptornis — Prickletail Roraimia — Roraiman Barbtail Thripophaga — Speckled Spinetail, Softtails Limnoctites — ST Spinetail, SB Reedhaunter Cranioleuca — Spinetails Pseudasthenes — Canasteros Spartonoica — Wren-Spinetail Pseudoseisura — Cacholotes Mazaria – White-bellied -

Download File

Natural selection and demography shape the genomes of New World birds Lucas Rocha Moreira Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Lucas Rocha Moreira All Rights Reserved Abstract Natural selection and demography shape the genomes of New World birds Lucas Rocha Moreira Genomic diversity is shaped by the interplay between mutation, genetic drift, recombination, and natural selection. A major goal of evolutionary biology is to understand the relative contribution of these different microevolutionary forces to patterns of genetic variation both within and across species. The advent of massive parallel sequencing technologies opened new avenues to investigate the extent to which alternative evolutionary mechanisms impact the genome and the footprints they leave. We can leverage genomic information to, for example, trace back the demographic trajectory of populations and to identify genomic regions underlying adaptive traits. In this disser- tation, I employ genomic data to explore the role of demography and natural selection in two New World bird systems distributed along steep environmental gradients: the Altamira Oriole (Icterus gularis), a Mesoamerican bird that exhibits large variation in body size across its range, and the Hairy and Downy woodpecker (Dryobates villosus and D. pubescens), two sympatric species whose phenotypes vary extensively in response to environments in North America. In Chapter 1, I combine ecological niche model, phenotypic and ddRAD sequencing data from several individuals of I. gularis to investigate which spatial processes best explain geographic variation in phenotypes and alleles: (i) isolation by distance, (ii) isolation by history or (iii) isolation by environment. -

Geographic Variation, Zoogeography, and Possible Rapid Evolution in Some Cranioleuca Spinetails (Furnariidae) of the Andes

THE WILSON BULLETIN A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF ORNITHOLOGY Published by the Wilson Ornithological Society VOL. 96, No. 4 DECEMBER 1984 PAGES 5 15-775 Wilson Bull., 96(4), 1984, pp. 5 15-523 GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION, ZOOGEOGRAPHY, AND POSSIBLE RAPID EVOLUTION IN SOME CRANIOLEUCA SPINETAILS (FURNARIIDAE) OF THE ANDES J. V. REMSEN, JR. The humid slopes of the Andes Mountains of South America provide one of the worlds’ greatest natural laboratories for the study of evolution and zoogeography. Although the “population structure,” nature of geo- graphic variation, and location of zoogeographic boundaries have been described for numerous taxa of the puna and paramo zones of the Andes (Vuilleumier 1980) relatively little has been published concerning birds of the humid, forested eastern slopes. In this paper, I analyze the geo- graphic variation and distribution of the Cranioleuca albiceps superspe- ties (Fumariidae), here considered to consist of Light-crowned Spinetail (C. a/biceps) (with two subspecies), Marcapata Spinetail (C. marcapatae), and a previously undescribed form, here considered a subspecies of C. marcapatae, to be called: Cranioleuca marcapatae weskeisubsp. nov. HOLOTYPE.-American Museum of Natural History No. 820557; male from Cordillera Vilcabamba, elev. 3250 m, Dpto. Cuzco, Peru (12”36S,’ 733O’ W),’ 22 July 1968; John S. Weske, original number 1825. DIAGNOSIS.-Ventrally very similar to Crunioleuca m. marcupatae, but malar region more strongly washed buff; dorsally, virtually identical to white-crowned individuals of Cranioleuca a. -

Manu Expeditions Birding Tours

MANU EXPEDITIONS BIRDING TOURS Ph Photo Collin Campbell [email protected] www.Birding-In-Peru.com Marvellous Spatuletail – Gary Rosenberg A TRIP REPORT FOR A BIRDING TRIP TO THE MARAÑON ENDEMIC BIRD AREA, PERU. June 9-18 2011 Trip Leader and report redaction: Barry Walker With: Frank Hamilton, Stuart Housden, Tim Stowe, Ruaraidh Hamilton, Ian Darling, Andy Bunten and Colin Campbell A shortened more relaxed version of our North Peru tour and we had to rush a little bit but despite unusual rains for this time of year at Abra Patricia and low flock activity there we managed to see a wide variety of the special birds of this endemic area including 40 species of Hummingbirds most seen very well at feeding stations, record 28 true Peruvian endemic and 14 other range restricted species including several near endemics. Acomodations ranged from waterless basics in Celendin to luxury Spa’s in Cajamarca and a lot of good craic was had along the way. Thanks for the Noble Snipe! DAY BY DAY ACTIVITIES June 8th: Arrive in Lima June 9th: Flight to Tarapoto and onto Abra Patricia. On arrival we met our drivers Walter and Mario and our, essential, field chef Aurelio. We then drove towards Moyobamba where we had a late lunch where we saw a group of 50+ Oilbird roosting near the road!! Night Owlet Lodge 2200 meters, Department of San Martin. June 10th -11th: Two full days at the American Bird Conservancy sponsored Long -whiskered Owlet Lodge We spent our time between walking trails and birding the roadside at different elevations between the pass at 2200 meters down to 900 meters and everything in between. -

Phylogeny of Thripophagini Ovenbirds (Aves: Synallaxinae: Furnariidae)

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2019, 127, 826–846. With 3 figures. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/biolinnean/article/127/4/826/5509929 by HACETTEPE UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER LIBRARY user on 29 March 2021 Phylogeny of Thripophagini ovenbirds (Aves: Synallaxinae: Furnariidae) ESTHER QUINTERO1,2*, and UTKU PERKTAŞ1,3, 1Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY, USA 2Subcoordinación de Especies Prioritarias, Comisión Nacional Para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Liga Periférico Insurgentes Sur 4903, Parques del Pedregal, 14010 Tlalpan, Mexico 3Department of Biology (Zoology Section, Biogeography Research Lab.), Faculty of Science, Hacettepe University, Beytepe, 06800 Ankara, Turkey Received 13 March 2019; revised 9 April 2019; accepted for publication 10 April 2019 In this study, we address the evolutionary relationships and discuss the biogeographical history of a complex and diverse group of ovenbirds, the Thripophagini. We reconstruct the phylogeny and estimate the time of divergence of this group, using sequences from two complete mitochondrial genes (cytochrome b and NADH subunit 2) from a total of 115 fresh tissue samples. The results provide a better understanding of the phylogenetic relationships of the taxa within this group, some of which require a thorough taxonomic revision. We discuss the biogeographical history of the group, and find parallels with other previously studied Andean birds which may indicate that tectonic and climatic events might, at least in part, be linked to its diversification through the uplift of the Andes, the creation of new montane habitats and barriers, the evolution of Amazonian drainages and landscapes, and the climatic oscillations of the Pleistocene. -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds. -

Peru: Manu and Machu Picchu August 2010

Peru: Manu and Machu Picchu August 2010 PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu 13 – 30 August 2010 Tour Leader: Jose Illanes Itinerary: August 13: Arrival day/ Night Lima August 14: Fly Lima-Cusco, Bird at Huacarpay Lake/ Night Cusco August 15: Upper Manu Road/Night Cock of the Rock Lodge August 16-17: San Pedro Area/ Nights cock of the Rock Lodge August 18: San Pedro-Atalaya/Night Amazonia Lodge August 19-20: Amazonia Lodge/Nights Amazonia Lodge August 21: River Trip to Manu Wildlife Center/Night Manu Wildlife Center August 22-24: Manu Wildlife Center /Nights Manu Wildlife Center August 25: Manu Wildlife Center - Boat trip to Puerto Maldonado/ Night Puerto Maldonado August 26: Fly Puerto Maldonado-Cusco/Night Ollantaytambo www.tropicalbirding.com Tropical Birding 1-409-515-0514 1 Peru: Manu and Machu Picchu August 2010 August 27: Abra Malaga Pass/Night Ollantaytambo August 28: Ollantaytambo-Machu Picchu/Night Aguas Calientes August 29: Aguas Calientes and return Cusco/Night Cusco August 30: Fly Cusco-Lima, Pucusana & Pantanos de Villa. Late evening departure. August 14 Lima to Cusco to Huacarpay Lake After an early breakfast in Peru’s capital Lima, we took a flight to the Andean city of Cusco. Soon after arriving in Cusco and meeting with our driver we headed out to Huacarpay Lake . Unfortunately our arrival time meant we got there when it was really hot, and activity subsequently low. Although we stuck to it, and slowly but surely, we managed to pick up some good birds. On the lake itself we picked out Puna Teal, Speckled and Cinnamon Teals, Andean (Slate-colored) Coot, White-tufted Grebe, Andean Gull, Yellow-billed Pintail, and even Plumbeous Rails, some of which were seen bizarrely swimming on the lake itself, something I had never seen before. -

The Importance of Suboscine Birds As Study Systems in Ecology and Evolution

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 23: 261–274, 2012 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society THE IMPORTANCE OF SUBOSCINE BIRDS AS STUDY SYSTEMS IN ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION Joseph A. Tobias 1, Jeff D. Brawn 2, Robb T. Brumfield 3, Elizabeth P. Derryberry 3, Alexander N. G. Kirschel 1,4, & Nathalie Seddon 1 1Edward Grey Institute, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, UK 2Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801 USA 3Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 4Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cyprus, PO Box 20537, Nicosia 1678, Cyprus Resumen. – La importancia del uso de Suboscines como sistema de estudio en ecología y evolución. – Las aves Suboscines son uno de los componentes más prominentes de la avifauna Neotropical, sin embargo aun son relativamente poco estudiados en comparación a su clado hermano, los Oscines. Esta situación parece estar cambiando rápidamente debido a Que los ornitólogos se han dado cuenta Que los suboscines ofrecen un sistema ideal de estudio para investigar una variedad de preguntas. Resumimos los resultados de un simposio enfocado en estudios de suboscines traQueofonos (trepapalos, furnáridos, hormigueros y afines) y destacamos avances recientes en nuestro entendimiento de su historia natural y comportamiento. Argumentamos Que debido a su antigüedad y altos niveles de diversidad, ellos son un excelente modelo para análisis comparativos y filogenéticos. Sobre todo, muchos de los detalles de su reproducción y comunicación los predisponen a que se realicen obser- vaciones de campo y estudios experimentales de interacciones sociales y de evolución de las señales, así como a técnicas de reconocimiento vocal.