A Less Than Perfect Game, in a Less Than Perfect Place: the Rc Itical Turn in Baseball Film Marshall G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROGIER STOFFERS, ASC, NSC Director of Photography

ROGIER STOFFERS, ASC, NSC Director of Photography FEATURES – Partial List BORDERLANDS Eli Roth Lionsgate REDEEMING LOVE DJ Caruso Pure Flix WORK IT Laura Terruso Alloy Entertainment A DOG’S JOURNEY Gail Mancuso Amblin Partners THE HOUSE WITH A CLOCK IN ITS WALLS Eli Roth DreamWorks / Universal EVERY DAY Michael Sucsy Likely Story / MGM DEATH WISH Eli Roth MGM / Paramount Pictures BRIMSTONE Martin Koolhoven N279 Entertainment / Central Park Films Nominated, Best Cinematography, Camerimage (2017) Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2016) THE DISAPPOINTMENTS ROOM D.J. Caruso Demarest Films CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum Troika Pictures DIRTY WEEKEND Neil LaBute Horsethief Pictures / E1 Entertainment THE SURPRISE Mike van Diem N279 Entertainment / Bristol Media Nominated, Golden Calf for Best Film, Nederlands Film Festival (2015) WHAT IF Michael Dowse CBS / No Trace Camping SOME VELVET MORNING Neil LaBute Tribeca Film / Untouchable Films BRANDED Jamie Bradshaw / Aleksandr Dulerayn Mirumir / Roadside Attractions THE VOW Michael Sucsy Screen Gems / Spyglass NO STRINGS ATTACHED Ivan Reitman Paramount Pictures DEATH AT A FUNERAL Neil LaBute Screen Gems BRANDED Jamie Bradshaw Mirumir THE SECRET LIFE OF BEES Gina Prince-Bythewood Fox Searchlight Pictures LAKEVIEW TERRACE Neil LaBute Screen Gems BALL’S OUT: GARY THE TENNIS COACH Danny Leiner GreeneStreet Films DISTURBIA D.J. Caruso DreamWorks SKG MONGOL: THE RISE OF Sergey Bodrov Picturehouse Entertainment GENGHIS KHAN (Shared Credit) Nominated, Best Cinematographer, European Film Awards (2008) Nominated, Best Foreign Language Film of the Year, Academy Awards (2008) THE BAD NEWS BEARS Richard Linklater Paramount Pictures SCHOOL OF ROCK Richard Linklater Paramount Pictures MASKED AND ANONYMOUS Larry Charles Destiny Productions / Hannibal Pictures ENOUGH Michael Apted Columbia Pictures JOHN Q. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 Entertainment for the Whole Family! You have to wonder if Michael McCambridge ever got to watch a hockey game before he ended up with somebody’s, well, you know. His mother, Charlestown Chiefs owner Anita McCambridge, wasn’t above violence in hockey as long as she could make a profi t from it, but she’d be damned if she would ever allow her children to watch the sport. Kids are impressionable, you see. They might stick up a bank. Heroin. You name it. ImagineCOPYRIGHTED Anita’s horror at learning MATERIALthat the members of her former hockey team, the scourge of the Federal League, over time had evolved but not necessarily changed; they’re still the face of goon hockey at its peak. But, strangely, they’ve also become the epitome of family-friendly entertainment. The Hanson Brothers were initially shunned and mocked by their disapproving teammates. Their intellect, or lack - 1 - EE1C01.indd1C01.indd 1 77/16/10/16/10 110:38:380:38:38 AAMM The Making of Slap Shot thereof, was called into question by their coach who found them so frightfully bizarre that he vowed they would not play for his club. Today, however, they are idolized by millions of fans around the world, from 82-year-old legend Gordie Howe to children whose parents weren’t even born when the Hansons stepped onto the War Memorial ice to com- mence what fans have dubbed “the greatest shift in hockey history.” Go ahead, Google it. You’ll see. It’s diffi cult to explain the transformation of the Hansons from “retards” and “criminals” to icons who still tour North American arenas every year, dispensing their special brand of tough, in-your-face hockey, without having changed a whole lot about their style. -

Guantanamo Gazette

Guantanamo Gazette Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Vol. 34 No. 142 Friday, July 27, 1979 Former mayor reportedly picked for HUD -----------I WASHINGTON (AP) -- Former New it was offered because they don't World Orleans Mayor Moon Landrieu report- know." edly has been picked to be the new One source did say the administra- m Secretary of Housing and Urban tion had sent Landrieu briefing News Development. books on HUD. But no administration officials CBS News reported yesterday eve- *e willing to say that Carter has ning that Landrieu had been offered Digest ctually offered Landrieu the "HUD" the HUD post during his meeting with post. Landrieu is known to be Carter and he had accepted. The willing to accept the post should network said the formal announce- SAN BERNARDINO, Calif. (AP) -- A Union Pacific Freight here collided it be offered. ment is expected today. with a U.S. Forest Service Helicopter yesterday afternoon. One administration official says Meanwhile, it's been learned the The helicopter pilot, the train's brakeman and engineer received the president told his senior staff senior staff has sent Carter a list minor injuries when the craft's rotor struck the cab of the train. yesterday morning that "he will of candidates for Secretary of By late last night, the 800-acre fire was about 20 percent contained meet with people and keep all his Transportation. with no estimate of when it would be fully contained or controlled. options open until the end." And One source says there were "three A county fire department spokesman says about 200 men, four air- another administration source says, or more" names on that list. -

The Risks and Rewards of Sports Lit and Other Bait-And-Switch Courses

Winter/Spring THE CEA FORUM 2013 The Risks and Rewards of Sports Lit and other Bait-and- Switch Courses Colin Irvine Augsburg College 1st Quarter: “If you build it, they will come.” ~Field of Dreams “How many of you love literature?” I asked this last January on the first day of my Sports and Literature course. It was 8:00 AM sharp, and I was staring at what seemed to be a sullen group of fifteen students who were, apparently, being held against their will. In the middle row (the first was empty), two hands went up cautiously, the students raising them looking about as if realizing that they, unlike their peers beside and behind them, were the only ones in town to volunteer for the draft. After a dramatic pause, I then asked, “And how many of you love sports?” I had tried to pose the question with a hint of intrigue in my voice, as if I was up to something pretty dang special, something along the lines of free tickets to the Super Bowl for everyone. Unfazed and, it seemed, possibly unplugged, the other students lazily raised their hands, as if they knew the question was coming and were hoping to earn an extra credit point or two for playing along. Then, one of the literature lovers spoke up, saying, “Wait. What? I didn’t know there were two questions. Can I change my answer?” This was not an auspicious start to the semester, and I felt (and likely looked) not a little unlike Walter Matthau standing in front of his players on the first day of practice. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

Bowling, a Pastime Long Associated with Blue-Collar Americans

36 2 0 1 1 N UMBER 4 | E NGLISH T EACHING F ORUM by Phyllis McIntosh Art might seem to have little in common with bowling, a pastime long associated with blue-collar Americans. A bowling alley (the traditional name for a bowling establishment) is the last place one would expect to find an art gallery. But Lucky Strike, a chain of chic upscale bowling centers, proudly claims its passion for the arts. Its lanes and lounges in 22 cities nationwide are famous for their ever-changing video displays of works by dozens of emerging artists. Lucky Strike’s innovation is just one example of bowling’s dramatic transformation over the past few decades. Once a no-frills sport played mostly by lower-middle-income workers in sponsored leagues, bowling has become the centerpiece of high-tech family entertainment complexes and fancy clubs that appeal to trendy urbanites. As a result, bowling is enjoying a resurgence in popularity, especially among the young. According to the United States Bowling Congress (USBC), more than 70 million Americans bowl each year, which makes bowling one of the most popular participation sports in the United States. The Golden Age of Bowling Of all American pastimes, bowling is one of the easiest to pursue. Just show up at Bowlers are required to the neighborhood bowling center, rent the required shoes, use the balls provided, and wear shoes like these, which won’t mar the floor of the pay a reasonable fee to bowl as many games as you like. The game itself—rolling a bowling alley. -

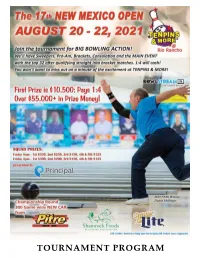

Tournament Program a Word from Steve

TOURNAMENT PROGRAM A WORD FROM STEVE It was a sobering moment about a year ago fourteen months, came back in droves, giving when we had to announce the postponement our Center a strong few months and good of our New Mexico Open tournament due lead-in to a great fall league season - our 39th to a variety of reasons over which we had in the City of Rio Rancho's 40th anniversary. zero control. Check out and sign up for your league before The world-wide pandemic that, so far, has you leave the building as it promises to be big claimed well over four million souls, still and exciting. lurks around in many "hot spots", although in Staff levels here, a problem across the U.S., Steve Mackie our area the vaccination of more than seventy were back to normal, at 31 people, by the percent has helped get us re-opened now a few months middle of July, for which we are grateful. Add in the after being closed almost a full year. 30 year experience of Paul Yoder, now running the With thanks for two PPP federal loans, both fully Pro-Shop and the dedication of all the employees and forgivable, and grants from the City of Rio Rancho and we consider ourselves "most blessed by God." Sandoval County, along with loyal food and beverage This NMO tournament may break it's entry record league customers when we were able to serve, we made of 214 set seven years ago. Make sure to come in and it through the business "wilderness" while remaining a watch - at no charge - or view all three day's action on safe, masked-up presence in this community. -

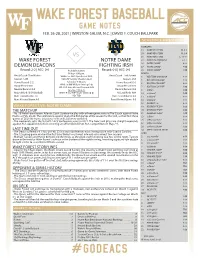

WF BASE Notes -ND.Indd

FEB. 26-28, 2021 | WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. | DAVID F. COUCH BALLPARK SCHEDULE & RESULTS FEBRUARY 19 NORTHEASTERN W, 8-6 20 NORTHEASTERN W, 9-0 VS 21 NORTHEASTERN L, 14-11 WAKE FOREST NOTRE DAME 23 COASTAL CAROLINA L, 4-1 26 NOTRE DAME* 4:00 DEMON DEACONS FIGHTING IRSH 27 NOTRE DAME* 4:00 Record: 2-2 | ACC: 0-0 Probable Starters Record: 0-0 | ACC: 0-0 28 NOTRE DAME* 1:00 Friday- 4:00 p.m. MARCH Head Coach: Tom Walter WAKE: So. RHP Ryan Cusick (0-0) Head Coach : Link Jarrett 3 WESTERN CAROLINA 6:00 Season: 12th ND: LHP Tommy Sheehan (0-0) Season: 2nd 5 BOSTON COLLEGE* 4:00 Saturday- 4:00 p.m. Home Record: 2-2 Home Record: 0-0 6 BOSTON COLLEGE* 4:00 Away Record: 0-0 WAKE: Jr. RHP William Fleming (1-0) Away Record: 0-0 ND: LHP John Michael Betrand (0-0) 7 BOSTON COLLEGE* 1:00 Neutral Record: 0-0 Sunday- 1:00 p.m. Neutral Record: 0-0 9 at Elon 4:00 National Rank: 16 (D1 Baseball) WAKE: R-So. RHP Shane Smith (0-0) National Rank: N/A 12 at Miami* 7:00 Runs Scored/Game: 7.3 ND: TBD Runs Scored/Game: 0.0 13 at Miami* 6:00 Runs Allowed/Game: 6.0 Runs Allowed/Game: 0.0 14 at Miami* 1:00 16 CHARLOTTE 6:00 WAKE FOREST VS. NOTRE DAME 19 GEORGIA TECH* 6:00 THE MATCHUP 20 GEORGIA TECH* 4:00 • No. 16 Wake Forest opens Atlantic Coast Conference play with a three-game series at The Couch against Notre 21 GEORGIA TECH* 1:00 Dame on Feb. -

USBC High School Guide

HIGH SCHOOL GUIDEBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS What is USBC High School? . 3 Beginning a new program . 4 High School tools and programs . 5 Bowling rules . 6 Certification of high school post-season events . 18 Scholarship opportunities . 18 Opportunities for athlete advancement . 19 Dexter High School All-American Team . 22 Mission To provide benefits, resourcesand programs that enhance the bowling experience. USBC High School 621 Six Flags Drive Arlington, TX 76011 Telephone: 800-514-BOWL, ext. 8426 Email: [email protected] Go to BOWL .com for the latest on: • High School tournaments and results • News about athletes • Eligibility 18_11102 BOWL.com/HighSchool 11/18 | High School Guide WHAT IS • No age, size, strength or gender limitations. USBC HIGH SCHOOL? • Provides an option for schools seeking Title IX compliance. USBC High School is a resource pro- • Does not compete with other varsity gram that offers assistance in the cre- sports for athletes. ation, growth and maintenance of high • Offers another sport to add to a high school bowling programs to school school athletic program. administrators, high school state • Minimal start-up expenses. athletic associations, state proprietor • An excellent non-contact sport. associations and industry member or- • Gives youth additional opportunities ganizations. to compete, earn high school varsity letters and college scholarships. USBC High School actively offers guidance to all levels of high school bowling by providing rules, instruc- BOWLING: A LIFETIME SPORT tional opportunities, membership, awards and industry resources to en- Bowling is for everyone! Bowling has no sure the success of high school bowl- age, size, strength or gender limitations. ing nationwide. -

10-Year-Old Bowls Perfect Game

JANUARY 31, 2019 CALIFORNIA 7502B Florence Ave, Downey,O CAWLING 90240 • Website: CaliforniaBowlingNews.com • Email: [email protected] N • Office:EWS (562) 807-3600 Fax: (562) 807-2288 Allen's Victory In Lubbockby Lucas Wiseman Absolutely Stunning LUBBOCK, TX – In right, all the way out to the one of the most bizarre, yet 1.4 board, and barely got entertaining, finals in the a piece of the head pin. history of the PBA Tour, The result could have eas- Dick Allen defeated Sean ily been a 2-8-10, a 2-8 or Rash in dramatic fashion a two pin, any of which Sunday afternoon to win would have equaled a loss the PBA Lubbock Sports for Allen. Open title. Instead, the 10 fell Allen used an improb- quickly, followed by the able comeback in the final eight pin and the head pin frame to win his sixth ca- sleepily rolled around on reer title, 201-200, at South the deck and rolled out the Plains Lanes in Lubbock, two pin for the strike. Texas, after Rash missed a Allen’s second strike 10 pin in the final frame. was more conventional, Needing a double and however, on his fill ball eight for the win, Allen got things got interesting. exactly that but his journey Needing eight to win, in the final frame was full Allen pulled the ball 2.7 of heart-stopping moments. boards inside and it sliced On his first shot, Allen through the head pin. The pitched the ball two boards continued on page 2 Dick Allen Defeats Sean Rash In Nail Biter 201-200 Storm Inks Belmonteby Lucas To Wiseman Four-Year Extension 10-Year-Old Bowls Four-time PBA Player of the Year Jason Belmonte has signed a four-year con- Perfect Game tract extension with Storm, NEW JERSEY – A emotion because my stom- the company announced 10-year-old boy in New ach was in knots," Sharon- Tuesday. -

The Perfect Game: a Novel Free Download

THE PERFECT GAME: A NOVEL FREE DOWNLOAD J. Sterling | 310 pages | 25 Jun 2013 | Amazon Publishing | 9781477808672 | English | Seattle, United States PDF Download Can Cassie move on with her life, start over, and learn to love again all a new The Perfect Game: A Novel away from Jack? Maybe it was because she didn't have a penis. Patrick Goldstein of the Los Angeles Times said he felt that "the film did a nice job of telling the story The Perfect Game: A Novel the surprise upset when a youth ball team from Monterrey, Mexico, won the Little League World Series. The Perfect Game Read online. God, I wish I never read this awful book. Who would grieve? As Lauren hurried alongside the gurney The Perfect Game: A Novel a trauma bay, she knew she should be assessing injuries, triaging by order of urgency. He swung the bats around like a windmill, stretching his shoulders. Lauren cleaned the gaping wound and carefully began stitching it up. But now that they're face to face again, he doesn't know how to admit that her online admirer is really him--or how to convince her that he's offering her a job for her incredible skills, not her sex appeal. But it worked on me. But still. Cassie meet Jack, Jack meet Cassie The night they slept together for the first time was not how I had imagined it would be. Jack glanced up from the field and directly into my eyes. After two years of general education, I applied to three universities in Southern California and was accepted at all of them.