The Risks and Rewards of Sports Lit and Other Bait-And-Switch Courses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROGIER STOFFERS, ASC, NSC Director of Photography

ROGIER STOFFERS, ASC, NSC Director of Photography FEATURES – Partial List BORDERLANDS Eli Roth Lionsgate REDEEMING LOVE DJ Caruso Pure Flix WORK IT Laura Terruso Alloy Entertainment A DOG’S JOURNEY Gail Mancuso Amblin Partners THE HOUSE WITH A CLOCK IN ITS WALLS Eli Roth DreamWorks / Universal EVERY DAY Michael Sucsy Likely Story / MGM DEATH WISH Eli Roth MGM / Paramount Pictures BRIMSTONE Martin Koolhoven N279 Entertainment / Central Park Films Nominated, Best Cinematography, Camerimage (2017) Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2016) THE DISAPPOINTMENTS ROOM D.J. Caruso Demarest Films CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum Troika Pictures DIRTY WEEKEND Neil LaBute Horsethief Pictures / E1 Entertainment THE SURPRISE Mike van Diem N279 Entertainment / Bristol Media Nominated, Golden Calf for Best Film, Nederlands Film Festival (2015) WHAT IF Michael Dowse CBS / No Trace Camping SOME VELVET MORNING Neil LaBute Tribeca Film / Untouchable Films BRANDED Jamie Bradshaw / Aleksandr Dulerayn Mirumir / Roadside Attractions THE VOW Michael Sucsy Screen Gems / Spyglass NO STRINGS ATTACHED Ivan Reitman Paramount Pictures DEATH AT A FUNERAL Neil LaBute Screen Gems BRANDED Jamie Bradshaw Mirumir THE SECRET LIFE OF BEES Gina Prince-Bythewood Fox Searchlight Pictures LAKEVIEW TERRACE Neil LaBute Screen Gems BALL’S OUT: GARY THE TENNIS COACH Danny Leiner GreeneStreet Films DISTURBIA D.J. Caruso DreamWorks SKG MONGOL: THE RISE OF Sergey Bodrov Picturehouse Entertainment GENGHIS KHAN (Shared Credit) Nominated, Best Cinematographer, European Film Awards (2008) Nominated, Best Foreign Language Film of the Year, Academy Awards (2008) THE BAD NEWS BEARS Richard Linklater Paramount Pictures SCHOOL OF ROCK Richard Linklater Paramount Pictures MASKED AND ANONYMOUS Larry Charles Destiny Productions / Hannibal Pictures ENOUGH Michael Apted Columbia Pictures JOHN Q. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 Entertainment for the Whole Family! You have to wonder if Michael McCambridge ever got to watch a hockey game before he ended up with somebody’s, well, you know. His mother, Charlestown Chiefs owner Anita McCambridge, wasn’t above violence in hockey as long as she could make a profi t from it, but she’d be damned if she would ever allow her children to watch the sport. Kids are impressionable, you see. They might stick up a bank. Heroin. You name it. ImagineCOPYRIGHTED Anita’s horror at learning MATERIALthat the members of her former hockey team, the scourge of the Federal League, over time had evolved but not necessarily changed; they’re still the face of goon hockey at its peak. But, strangely, they’ve also become the epitome of family-friendly entertainment. The Hanson Brothers were initially shunned and mocked by their disapproving teammates. Their intellect, or lack - 1 - EE1C01.indd1C01.indd 1 77/16/10/16/10 110:38:380:38:38 AAMM The Making of Slap Shot thereof, was called into question by their coach who found them so frightfully bizarre that he vowed they would not play for his club. Today, however, they are idolized by millions of fans around the world, from 82-year-old legend Gordie Howe to children whose parents weren’t even born when the Hansons stepped onto the War Memorial ice to com- mence what fans have dubbed “the greatest shift in hockey history.” Go ahead, Google it. You’ll see. It’s diffi cult to explain the transformation of the Hansons from “retards” and “criminals” to icons who still tour North American arenas every year, dispensing their special brand of tough, in-your-face hockey, without having changed a whole lot about their style. -

Guantanamo Gazette

Guantanamo Gazette Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Vol. 34 No. 142 Friday, July 27, 1979 Former mayor reportedly picked for HUD -----------I WASHINGTON (AP) -- Former New it was offered because they don't World Orleans Mayor Moon Landrieu report- know." edly has been picked to be the new One source did say the administra- m Secretary of Housing and Urban tion had sent Landrieu briefing News Development. books on HUD. But no administration officials CBS News reported yesterday eve- *e willing to say that Carter has ning that Landrieu had been offered Digest ctually offered Landrieu the "HUD" the HUD post during his meeting with post. Landrieu is known to be Carter and he had accepted. The willing to accept the post should network said the formal announce- SAN BERNARDINO, Calif. (AP) -- A Union Pacific Freight here collided it be offered. ment is expected today. with a U.S. Forest Service Helicopter yesterday afternoon. One administration official says Meanwhile, it's been learned the The helicopter pilot, the train's brakeman and engineer received the president told his senior staff senior staff has sent Carter a list minor injuries when the craft's rotor struck the cab of the train. yesterday morning that "he will of candidates for Secretary of By late last night, the 800-acre fire was about 20 percent contained meet with people and keep all his Transportation. with no estimate of when it would be fully contained or controlled. options open until the end." And One source says there were "three A county fire department spokesman says about 200 men, four air- another administration source says, or more" names on that list. -

A Less Than Perfect Game, in a Less Than Perfect Place: the Rc Itical Turn in Baseball Film Marshall G

Boise State University ScholarWorks Communication Faculty Publications and Department of Communication Presentations 1-1-2013 A Less Than Perfect Game, in a Less Than Perfect Place: The rC itical Turn in Baseball Film Marshall G. Most Robert Rudd Boise State University Publication Information Most, Marshall G.; and Rudd, Robert. (2013). "A Less Than Perfect Game, in a Less Than Perfect Place: The rC itical Turn in Baseball Film". The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2011-2012, 180-195. From The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2011 -- 2012, © 2013. Edited by William M. Simons, used by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. www.mcfarlandpub.com. A Less Than Perfect Game, in a Less Than Perfect Place: The N Critical Turn in Baseball Film o N I Marshall G. Most and Robert Rudd He can't speak much English, but that's the beauty of baseball. If he can go to his right and hit the broad side of a barn, that'll do all his talking for him. - Big Leaguer, 1953 This reassuring voice-over, in reference to New York Giants minor league prospect Chuy Ramon Santiago Aguilar, sums up nicely a fundamental tenet of baseball ideology: race, ethnicity, and cultural heritage do not matter. All are welcome to participate in the national pastime. All will be treated equally. All that matters is how one plays the game. Such has been the promise of Amer- ica, as well, articulated in the values and aspirations of this, its national pas- time. Of course, this has not been baseball's true history, nor America's. -

Life Is Good at the Barrington!

The Like Us! Barrington Lifestyle Assisted Living 901 Seminole Blvd. • Largo, FL 33770 • 727-585-5900 • www.barringtonseniorliving.com July 2015 Baseball at the Box Office “There’s no crying in baseball!” “If you build Happy Birthday, it, he will come.” These memorable lines are America, the Fourth among many from baseball-themed movies through the years. Catch a few of these of July Is Upon Us! popular titles: Though fireworks, picnics and parades are all “The Pride of the Yankees” (1942) — Gary a part of the festivities, Americans gather to Cooper stars in this sentimental biopic of Hall of celebrate freedom. For your patriotic pleasure, Famer Lou Gehrig. here’s a compilation of inspiring quotes for “The Bad News Bears” (1976) — A former Independence Day: minor league ballplayer coaches a ragtag Little “Freedom is never dear at any price. It is the League team of comic misfits. breath of life. What would a man not pay for “The Natural” (1984) — A middle-aged slugger living?” — Gandhi gets a second chance at the big leagues, where “Liberty, taking the word in its concrete sense, he faces secrets from his past. consists in the ability to choose.” “Eight Men Out” (1988) — This is the dramatic — Simone Well account of the infamous Black Sox scandal, in “The secret of happiness is freedom, the secret which eight Chicago White Sox players accepted of freedom is courage.” — Carr Jones bribes to purposely lose the 1919 World Series. “Our greatest happiness does not depend on the “Field of Dreams” (1989) — Part fairy tale, part condition of life in which chance has placed drama, this story about second chances strikes a us, but is always the result of good conscience, chord with fathers and sons. -

16-247 BOARD REPORT Noo ______

~~l~~;oEJ? BOARD OF RECREATION AND PARK COMMISSIONERS 16-247 BOARD REPORT NOo ______ DATE December 14, 2016 C. D. __---'5=c....- __ BOARD OF RECREATION AND PARK COMMISSIONERS SUBJECT: WESTWOOD PARK - BAD NEWS BEARS BASEBALL FIELD IMPROVEMENT (PRJ21090) PROJECT - APPROPRIATION FROM UNRESERVED AND UNDESIGNATED FUND BALANCE IN FUND 302 - EXEMPTION FROM THE CALIFORNIA ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY ACT (CEQA) PURSUANT TO ARTICLE III, SECTION 1, CLASS 1 (1 ,3) AND CLASS 11 (3) OF THE CITY CEQA GUIDELINES AP Diaz v. Israel fr·R. Barajas C:saQ K. Regan H. Fujita N. Williams f. ~ ~ 8 ev) '1 'p- Ion..- General Manager Approved __-...:. / ____ Disapproved ______ Withdrawn ____ RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Approve the scope of Westwood Park - Bad News Bears Baseball Field Improvement (PRJ21090) project (Project), as described in the Summary of this Report; 2. Subject to approval by the Mayor, authorize the appropriation of Two Hundred Four Thousand, Five Hundred Dollars ($204,500.00) in Fund 302, Department 89, to Account TBD; FROM: Unreserved and Undesignated Fund Balance $204,500.00 TO: Fund 302J89JAccount TBD $204,500.00 3. Find that the proposed Project is categorically exempt from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), and direct Department of Recreation and Parks (RAP) staff to file a Notice of Exemption; 4. Authorize the RAP Chief Accounting Employee to prepare a check to the Los Angeles County Clerk in the amount of $75.00 for the purpose of filing a Notice of Exemption; and, 5. Authorize RAP's Chief Accounting Employee to make technical corrections as necessary to carry out the intent of this Report. -

The Hollywood Sports Film: Visualizing Hidden and Familiar Aspects of American Culture Englert, Barbara

www.ssoar.info The Hollywood Sports Film: Visualizing Hidden and Familiar Aspects of American Culture Englert, Barbara Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Englert, B. (2018). The Hollywood Sports Film: Visualizing Hidden and Familiar Aspects of American Culture. Historical Social Research, 43(2), 165-180. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.43.2018.2.165-180 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-57678-6 The Hollywood Sports Film – Visualizing Hidden and Familiar Aspects of American Culture ∗ Barbara Englert Abstract: »Der Hollywoodsportfilm. Eine Visualisierung verborgener und ver- trauter Aspekte der amerikanischen Kultur«. This essay highlights a number of Hollywood sport films from the 1970s focusing on national and personal iden- tity issues. Against the backdrop of contemporary history, the meaning of sports and film, and its pop cultural intertwinement becomes transparent re- vealing a basic pattern. Aspects come into the picture which from a European perspective seem both familiar and, in a way, hidden. Besides being great en- tertainment, sport films like North Dallas Forty (1979), Semi-Tough (1977) or The Bad News Bears (1976) have the quality to serve as a rich and meaningful archive of visual sources for research in the humanities. -

Activities Calender Submarine Sandwich Which Is Served in the Goodwood Thursday

Page Fhre Volume vs. Audience: A Homecoming Concert by Robert Brawn needed in order to mask the guitar, electric bass, two Winter Brothers Band which monies, they had a few really Wielding his fiddle like a echo which resulted from the drummers, a piano and Char- served as the warm up act. good tunes that, if played at conductor's baton, Charlie bad acoustics in the hall. lie, who switched from guitar Volume also was their ruin. half the volume, would have Daniels brought to a close For those who could tolerate to fiddle. Although they lacked in techn- been very entertaining and Homecoming week with an the volume, however, the A note is needed on The ical expertise and vocal har- pleasing to the listener. ear-shattering concert for a show wasn't a complete loss. near-capacity crowd in Brog- The first big highlight in the den Hall Sunday night, Jan. show was a drum duet. The 30. duet was very exciting because Clad in blue jeans, flannel both drummers played a diffe- shirt and a big hat Charlie rent music line while sounding introduced the audience to his like one drummer. m own brand of country rock as The second high spot was he stood bigger-than-life be- when Charlie played "Long- fore them. Haired Country Boy". The Unfortunately, the expertise crowd went wild acknowledg- of the musicians was oversha- ing his big hit. dowed considerably by a deaf- Returning for the first of two \ ening volume, so loud that encores, Charlie had everybo- only the hard of hearing could dy dancing as he incited them appreciate it. -

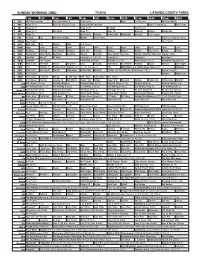

Sunday Morning Grid 7/10/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/10/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) European PGA Tour Golf Haas F1: America’s Bruce Cook 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Explore Wimbledon 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 2016 U.S. Women’s Open 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage The Radio Job. Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Formula One Racing British Grand Prix. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Montana Kaimin, December 8, 1976 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 12-8-1976 Montana Kaimin, December 8, 1976 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, December 8, 1976" (1976). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 6558. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/6558 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coal, solar heat may warm UM By PATRICK SHEEHY and the fourth" projects started with Montana Kaimln Raportar state funds, he said. UM President Richard Bowers Solar power, coal and garbage said Monday that he created the may be heating University of Mon committee to use UM resources in tana buildings in the not-too-distant energy conservation and to find future, a member of the campus alternative energy sources. energy committee said last week. Bowers said the UM committee will Richard Sheridan, UM associate work with other energy conservation professor of botany and en committee members from other vironmental studies, said UM may be Montana University System schools. forced to use only alternative forms of energy If natural gas reserves con Building Insulation tinue to dwindle and fuel prices rise.