Romeo and Juliet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

615. Miyazaki Fumiko and Duncan Williams

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 2001 28/3–4 The Intersection of the Local and the Translocal at a Sacred Site The Case of Osorezan in Tokugawa Japan MIYAZAKI Fumiko and Duncan WILLIAMS Osorezan is often portrayed today as a remote place in the Shimokita Peninsula, a borderland between this world and the other world, where female mediums called itako communicate with the dead. This article is an attempt to sketch the historical development of Osorezan with evidence from local archives, travel records, temple collections, and inscriptions from stone monuments. With newly available local historical data, despite what temple pamphlets claim, we will establish that the cult of Jizõ (and the death-associated rituals associated with the bodhisattva) was a late Tokugawa-period development and that the female mediums who have made the site so famous only began their communications with the dead at the mountain in the twentieth century. Indeed, what the historical evi- dence suggests is that Osorezan was a complex site that developed late for a major pilgrimage destination, in which the other-worldly concern with the dead (through the worship of Jizõ) was only one aspect of the Osorezan cult. Major patrons of Osorezan in the Tokugawa period prayed for the success of their commercial enterprises there and local people viewed the site primarily as a place of hot spring cures. This article will examine the his- tory of Osorezan from its emergence as a local religious site during the mid- seventeenth until the end of the Tokugawa period, when it became a pilgrimage destination known throughout Japan. -

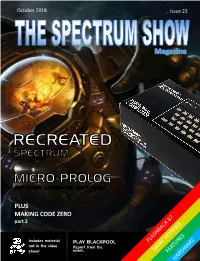

MAKING CODE ZERO Part 2

October 2018 Issue 23 PLUS MAKING CODE ZERO part 2 Includes material PLAY BLACKPOOL not in the video Report from the show! event... CONTENTS 32. RECREATED SPECTRUM Is it any good? 24. MIND YOUR LANGUAGE 18. Play Blackpool 2018 Micro-Prolog. The recent retro event. FEATURES GAME REVIEWS 4 News from 1987 DNA Warrior 6 Find out what was happening back in 1987. Bobby Carrot 7 14 Making Code Zero Devils of the Deep 8 Full development diary part 2. Spawn of Evil 9 18 Play Blackpool Report from the recent show. Hibernated 1 10 24 Mind Your Language Time Scanner 12 More programming languages. Maziacs 20 32 Recreated ZX Spectrum Bluetooth keyboard tested. Gift of the Gods 22 36 Grumpy Ogre Ah Diddums 30 Retro adventuring. Snake Escape 31 38 My Life In Adventures A personal story. Bionic Ninja 32 42 16/48 Magazine And more... Series looking at this tape based mag. And more…. Page 2 www.thespectrumshow.co.uk EDITORIAL Welcome to issue 23 and thank you for taking the time to download and read it. Those following my exploits with blown up Spectrums will be pleased to I’ll publish the ones I can, and provide hear they are now back with me answers where fit. Let’s try to get thanks to the great service from Mu- enough just for one issue at least, that tant Caterpillar Games. (see P29) means about five. There is your chal- Those who saw the review of the TZX All machines are now back in their lenge. Duino in episode 76, and my subse- cases and working fine ready for some quent tweet will know I found that this The old school magazines had many filming for the next few episodes. -

Idalia; Or, the Adventuress

IDALIA; OR, THE ADVENTURESS. IN THREE ACTS. GEORGE ROBERTS, (Member of the Dramatic Authors' Society) AUTHOR OF Lady Audley's Secret, Under the Rose, Three Furies, Forty Winks, Cousin Tom, Ample Apology, &c, &c. THOMAS HAILES LACY, THEATRICAL PUBLISHER, LONDON. IDALIA. First produced at the Royal St. James's Theatre (under the management of Miss Herbert), on Monday, April 22nd, 1867. This Drama is in part founded on the novel, " Idalia," by Onida. HUGH STONELEIGH ................ Mr. C. WYNDHAM. COUNT FALCON ................. Mr. HENRY IRVING. VICTOR VANE ... ................. Mr. F. CHARLES. VOLPONE VITELLO ... ... Mr. J. D. STOYLE. BAEON LINTZ (of the Austrian Army) Mr. GASTON MORRAY. CAPTAIN DELAFOSSE (of the Zouaves) Mr. WILTON. JOSEPH (Garcon at the Cafe) Mr. ALLEN. SCHWARTZ ... (a Croat) ... Mr. BRIDGFORD. BATZ ... (an Innkeeper) ... Mr. RIVERS. FILIPPO ... (Postillion) ... Mr. BROWNE. ENSIGN SCHWEITZER ... Mr. MERVIN. PICCOLO................................................... Mr. MONRO. BOTTEGA ... (a Savoyard)... Mr. SHARPE. BERTO ... (a Boy) ... Miss GUNNISS. IDALIA, COUNTESS GLORIA... Miss HERBERT. MADAME PARA VENT ...................Mrs. FRANK MATTHEWS. CERISE ................................. Miss K. KEARNEY. MADEMOISELLE PETITCHAT ... Miss BRUCE. VIOLETTA ................................. Miss THOMPSON. BIBI ... ... ... ... Miss AUSTIN. LULU ... ... ... Miss SMITHSON. Masquers, Croats, Zouaves, French and Austrian Soldiers, Vivan- dieres, Flower Girls, Monks, Peasants, &c. PERIOD—1859, during the Struggle for Italian Independence. Time of Representation—Two hours and fifteen minutes. IDALIA. ACT I. POST HOUSE ON THE SIMPLON PASS. GORGE OF GONDO. An interval of Two Months is supposed to elapse between the First and Second Acts. ACT II. THE VILLA BEATA—LAGO DI GARDA. GARDEN OF THE VILLA. GROTTO ON THE SHORE OF THE LAKE. ACT III. ROAD NEAR SAN MARTINO. SOLFERINO FROM THE SPIA D'ITALIA. -

Proquest Dissertations

BUTTERFLIES, TURBULENCE, GROWTH: VOICES OF LOVE Donna Safatli A Thesis In The Department Of Sociology and Anthropology Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April, 2008 © Donna Safatli, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40846-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40846-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Department of Educational Psychology

UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA THE LiVED EXPEFUENCE OF ADOLESCENT LOVE WENDY JOAN AUSTIN (-J A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY EDMONTON, ALBERTA FALL 1997 National iibmry Bibliotheque nationale I*(of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services seruices bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON KlAON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/£ïlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. 1 am fourteen and my skin has betrayed me the boy 1 canot live without sucks his thumb in secret how corne my knees are always so ashy what if 1 die before morning and momma's in the bedroom with the door closed. First verse of Hanginp Fire fiorn Undersong by Audre torde. -

The Vilcek Foundation Celebrates a Showcase Of

THE VILCEK FOUNDATION CELEBRATES A SHOWCASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS AND FILMMAKERS OF ABC’S HIT SHOW EXHIBITION CATALOGUE BY EDITH JOHNSON Exhibition Catalogue is available for reference inside the gallery only. A PDF version is available by email upon request. Props are listed in the Exhibition Catalogue in the order of their appearance on the television series. CONTENTS 1 Sun’s Twinset 2 34 Two of Sun’s “Paik Industries” Business Cards 22 2 Charlie’s “DS” Drive Shaft Ring 2 35 Juliet’s DHARMA Rum Bottle 23 3 Walt’s Spanish-Version Flash Comic Book 3 36 Frozen Half Wheel 23 4 Sawyer’s Letter 4 37 Dr. Marvin Candle’s Hard Hat 24 5 Hurley’s Portable CD/MP3 Player 4 38 “Jughead” Bomb (Dismantled) 24 6 Boarding Passes for Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 5 39 Two Hieroglyphic Wall Panels from the Temple 25 7 Sayid’s Photo of Nadia 5 40 Locke’s Suicide Note 25 8 Sawyer’s Copy of Watership Down 6 41 Boarding Passes for Ajira Airways Flight 316 26 9 Rousseau’s Music Box 6 42 DHARMA Security Shirt 26 10 Hatch Door 7 43 DHARMA Initiative 1977 New Recruits Photograph 27 11 Kate’s Prized Toy Airplane 7 44 DHARMA Sub Ops Jumpsuit 28 12 Hurley’s Winning Lottery Ticket 8 45 Plutonium Core of “Jughead” (and sling) 28 13 Hurley’s Game of “Connect Four” 9 46 Dogen’s Costume 29 14 Sawyer’s Reading Glasses 10 47 John Bartley, Cinematographer 30 15 Four Virgin Mary Statuettes Containing Heroin 48 Roland Sanchez, Costume Designer 30 (Three intact, one broken) 10 49 Ken Leung, “Miles Straume” 30 16 Ship Mast of the Black Rock 11 50 Torry Tukuafu, Steady Cam Operator 30 17 Wine Bottle with Messages from the Survivor 12 51 Jack Bender, Director 31 18 Locke’s Hunting Knife and Sheath 12 52 Claudia Cox, Stand-In, “Kate 31 19 Hatch Painting 13 53 Jorge Garcia, “Hugo ‘Hurley’ Reyes” 31 20 DHARMA Initiative Food & Beverages 13 54 Nestor Carbonell, “Richard Alpert” 31 21 Apollo Candy Bars 14 55 Miki Yasufuku, Key Assistant Locations Manager 32 22 Dr. -

Faust in France 12-21-12.Fdx

Faust in France by Christopher Shorr An Adaptation of "The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus" by Christopher Marlowe Christopher Shorr 1010 N. New Street Bethlehem, PA 18018 [email protected] 484-695-3564 CHARACTERS FAUST, a scientist for the German Army. HABER, Faust's friend and accomplished chemist. Inventor of scientific process used to generate poison gas in WWI. CLARA, Haber's dead wife. Also a chemist. HANS, a male German soldier. Re-animated to play: SIN OF THE TRENCH, FRIAR and ATTENDANT. ANNA, a young female German soldier. Re-animated to play: SIN OF NO MAN'S LAND, THE DUCHESS SOPHIE and FRIAR FRITZ, a waterboy for the German army. Re-animated to play: SIN OF MUSTARD GAS and Faust's puppet JURGEN, a young male German Soldier. Re-animated to play: SIN OF BOY SOLDIER, ARCHDUKE FERDINAND and FRIAR ERNST, a male German soldier. Re-animated to play: SIN OF SHELL SHOCK, THE POPE and ATTENDANT KARL, a male German soldier. Re-animated to play: SIN OF JEALOUSY OF NATIONS, FRIAR and EMPEROR FRANZ JOESPH HAUPTMANN, a male German soldier who outranks the others. Re- animated to play: SIN OF MACHINE GUN, ATTENDANT and CARDINAL OF LORRAIN CHORUS/LUCIFER, king of Hell. MEPHISTOPHILIS, Lucifer's servant in Hell. GOOD ANGEL EVIL ANGEL NOTE: This development of this script included an initial production at Moravian College in Bethlehem, PA, followed by a development workshop and reading at Wellfleet Harbor Actor's Theatre as part of the WHAT Lab series supported in part by Moravian College's Faculty Development and Research Committee. -

2008 Research Report on Child Labour

Research Report No.3 Small Hands A Survey Report on Child Labour in China www.clb.org.hk September 2007 I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................3 II. THE PRINCIPAL CHARACTERISTICS AND LEGAL PROHIBITION OF CHILD LABOUR IN CHINA.................................................................................................5 1. Defining child labour ...................................................................................................5 Regular workers (zhengshi de gugong) .............................................................................5 Casual workers (waichu banggong)..................................................................................5 Household helpers (jiating banggong) ..............................................................................6 Apprentices (xuetu)............................................................................................................6 Work-study students (qingong jianxue) .............................................................................6 Forced labourers (nugong)................................................................................................7 2. The regional, gender and economic characteristics of child labour........................7 3. Laws and government measures prohibiting the use of child labour .....................8 Legal Prohibitions on child labour....................................................................................8 Government -

Indhold Getting LOST

Indhold Getting LOST ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Fremgangsmåde og afgrænsningsfelt ............................................................................................................... 4 Beskrivelse af serien .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Føljetonformatet ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Episodernes opbygning og seriens plots ....................................................................................................... 7 Karaktererne .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Jacks plotlinje ................................................................................................................................................. 9 White Rabbit’s konstruktion og karakterfremstilling .................................................................................. 10 316’s konstruktion og karakterfremstilling ................................................................................................. 15 En strukturalistisk analyse af karakterens konstruktion ............................................................................. 19 Psychologial traits/habitual -

Cape Coral Daily Breeze

Batter up North Fort Myers CAPE CORAL goes down — SPORTS DAILY BREEZE WEATHER: Partly Cloudy • Tonight: Partly Cloudy • Thursday: Mostly Cloudy — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 39 Wednesday, February 18, 2009 50 cents Florida report: School district misused funds “While we respect the auditor’s authori- $3.6M loss if bill is not passed ty to interpret statute and examine our financial records according to their By MCKENZIE CASSIDY trict money unless a bill can be money from its capital account to interpretations, we do not agree with the [email protected] passed that expands the definition cover its $19 million computer finding related to our two mill funds.” A report released by the Florida of capital expenses. upgrade. Auditor General this month found State law requires the school Florida statutes contend that — Superintendent James Browder a significant deficiency in how the district to use ad valorem taxes for computer software purchases are Lee County School District man- capital outlay projects or purchas- not listed under allowable capital ages funds from ad valorem taxes, es including construction or main- purchases, although in October paying for personnel time and con- may lose $3.6 million from its something that may cost the dis- tenance, but according to the audit 2007 the school board approved sultant costs with the funds. operation account — used to pay in 2005 to 2006, the district took purchasing the software, as well as As a result, the school district See REPORT, page 6A Authorities seek two in Key West boat homicide Seen driving vehicle of missing Cape man By CONNOR HOLMES ing investigation. -

美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 the Vocabulary Coverage in American

國立臺灣師範大學英語學系 碩 士 論 文 Master’s Thesis Department of English National Taiwan Normal University 美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 The Vocabulary Coverage in American Television Programs A Corpus-Based Study 指導教授:陳 浩 然 Advisor: Dr. Hao-Jan Chen 研 究 生:周 揚 亭 Yang-Ting Chou 中 華 民 國一百零三年七月 July, 2014 國 立 英 臺 語 灣 師 學 範 系 大 學 103 碩 士 論 文 美 國 影 集 的 字 彙 涵 蓋 量 語 料 庫 分 析 周 揚 亭 中文摘要 身在英語被視為外國語文的環境中,英語學習者很難擁有豐富的目標語言環 境。電視影集因結合語言閱讀與聽力,對英語學習者來說是一種充滿動機的學習 資源,然而少有研究將電視影集視為道地的語言學習教材。許多研究指出媒體素 材有很大的潛力能激發字彙學習,研究者很好奇學習者要學習多少字彙量才能理 解電視影集的內容。 本研究探討理解道地的美國電視影集需要多少字彙涵蓋量 (vocabulary coverage)。研究主要目的為:(1)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,分別需要 英國國家語料庫彙編而成的字族表(the BNC word lists)和匯編英國國家語料庫 (BNC)與美國當代英語語料庫(COCA)的字族表多少的字彙量;(2)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,不同的電視影集類型需要的字彙量;(3)分析出現在美國 影集卻未列在字族表的字彙,並比較兩個字族表(the BNC word lists and the BNC/COCA word lists)的異同。 研究者蒐集六十部美國影集,包含 7,279 集,31,323,019 字,並運用 Range 分析理解美國影集需要分別兩個字族表的字彙量。透過語料庫的分析,本研究進 一步比較兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。 研究結果顯示,加上專有名詞(proper nouns)和邊際詞彙(marginal words),英 國國家語料庫字族表需 2,000 至 7,000 字族(word family),以達到 95%的字彙涵 蓋量;至於英國國家語料庫加上美國當代英語語料庫則需 2,000 至 6,000 字族。 i 若須達到 98%的字彙涵蓋量,兩個字族表都需要 5,000 以上的字族。 第二,有研究表示,適當的文本理解需要 95%的字彙涵蓋量 (Laufer, 1989; Rodgers & Webb, 2011; Webb, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Webb & Rodgers, 2010a, 2010b),為達 95%的字彙涵蓋量,本研究指出連續劇情類(serial drama)和連續超 自然劇情類(serial supernatural drama)需要的字彙量最少;程序類(procedurals)和連 續醫學劇情類(serial medical drama)最具有挑戰性,因為所需的字彙量最多;而情 境喜劇(sitcoms)所需的字彙量差異最大。 第三,美國影集內出現卻未列在字族表的字會大致上可分為四種:(1)專有 名詞;(2)邊際詞彙;(3)顯而易見的混合字(compounds);(4)縮寫。這兩個字族表 基本上包含完整的字彙,但是本研究顯示語言字彙不斷的更新,新的造字像是臉 書(Facebook)並沒有被列在字族表。 本研究也整理出兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。為達 95%字彙涵 蓋量,英國國家語料庫的 4,000 字族加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識才足夠;而 英國國家語料庫合併美國當代英語語料庫加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識只需 3,000 字族即可達到 95%字彙涵蓋量。另外,為達 98%字彙涵蓋量,兩個語料庫 合併的字族表加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識需要 10,000 字族;英國國家語料 庫字族表則無法提供足以理解 98%美國影集的字彙量。 本研究結果顯示,為了能夠適當的理解美國影集內容,3,000 字族加上專有 名詞和邊際詞彙的知識是必要的。字彙涵蓋量為理解美國影集的重要指標之一, ii 而且字彙涵蓋量能協助挑選適合學習者的教材,以達到更有效的電視影集語言教 學。 關鍵字:字彙涵蓋量、語料庫分析、第二語言字彙學習、美國電視影集 iii ABSTRACT In EFL context, learners of English are hardly exposed to ample language input.