615. Miyazaki Fumiko and Duncan Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90w6w5wz Author Carter, Caleb Swift Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Caleb Swift Carter 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries by Caleb Swift Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor William M. Bodiford, Chair This dissertation considers two intersecting aspects of premodern Japanese religions: the development of mountain-based religious systems and the formation of numinous sites. The first aspect focuses in particular on the historical emergence of a mountain religious school in Japan known as Shugendō. While previous scholarship often categorizes Shugendō as a form of folk religion, this designation tends to situate the school in overly broad terms that neglect its historical and regional stages of formation. In contrast, this project examines Shugendō through the investigation of a single site. Through a close reading of textual, epigraphical, and visual sources from Mt. Togakushi (in present-day Nagano Ken), I trace the development of Shugendō and other religious trends from roughly the thirteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. This study further differs from previous research insofar as it analyzes Shugendō as a concrete system of practices, doctrines, members, institutions, and identities. -

Brooklyn Zen Center Practice Period Commitment Form Fall 2015

Brooklyn Zen Center Practice Period Commitment Form Fall 2015 The following three-page form is to support you in clarifying your intentions for the practice period. We have listed all practice period events of which we are currently aware so that you have ample time to schedule in the events you wish to attend. Please submit your practice period commitment form by Monday, September 14th to the jisha (teacher’s assistant), either in person or via [email protected]. Our mostly volunteer staff needs ample time to plan for the many roles and events that make up a practice period. Thank you! Please check the events you are committing to attend: ______ Wed, 9/16 Practice Period Opening Ceremony ______ Fri-Sun, 9/18-20 Three-day Retreat w/ Zenju Earthlyn Manuel ______ Sat, 9/26 Dharma Talk ______ Sat, 10/3 Dharma talk ______ Sat, 10/17 One-day Sit, 10am-6pm ______ Sun, 10/18 Half-day Sit, 10am-1pm ______ Sat, 10/24 Dharma talk ______ Wed, 10/28 Segaki Ceremony & Celebration ______ Sat, 10/31 Dharma Talk ______ Sat, 11/7 Dharma Talk ______ Sun, 11/15 Half-day Sit, 10am-1pm ______ Fri-Sun, 11/20-22 Three-day Workshop w/ Kaz Tanahashi ______ Sat, 12/5 Dharma Talk ______ Mon–Sun, 12/7–13 Rohatsu sesshin – 5 or 7 day participation permitted ______ Wed, 12/16 Practice period closing ceremony ______ I am committing to regular practice discussion with the following the following practice leader(s): Teah Strozer ______ Laura O’Loughlin ______ Greg Snyder ______ I am committing to the following ryo(s) (practice groups): doanryo (service practice led -

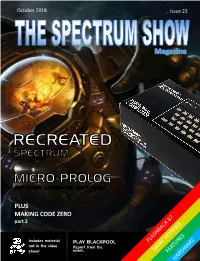

MAKING CODE ZERO Part 2

October 2018 Issue 23 PLUS MAKING CODE ZERO part 2 Includes material PLAY BLACKPOOL not in the video Report from the show! event... CONTENTS 32. RECREATED SPECTRUM Is it any good? 24. MIND YOUR LANGUAGE 18. Play Blackpool 2018 Micro-Prolog. The recent retro event. FEATURES GAME REVIEWS 4 News from 1987 DNA Warrior 6 Find out what was happening back in 1987. Bobby Carrot 7 14 Making Code Zero Devils of the Deep 8 Full development diary part 2. Spawn of Evil 9 18 Play Blackpool Report from the recent show. Hibernated 1 10 24 Mind Your Language Time Scanner 12 More programming languages. Maziacs 20 32 Recreated ZX Spectrum Bluetooth keyboard tested. Gift of the Gods 22 36 Grumpy Ogre Ah Diddums 30 Retro adventuring. Snake Escape 31 38 My Life In Adventures A personal story. Bionic Ninja 32 42 16/48 Magazine And more... Series looking at this tape based mag. And more…. Page 2 www.thespectrumshow.co.uk EDITORIAL Welcome to issue 23 and thank you for taking the time to download and read it. Those following my exploits with blown up Spectrums will be pleased to I’ll publish the ones I can, and provide hear they are now back with me answers where fit. Let’s try to get thanks to the great service from Mu- enough just for one issue at least, that tant Caterpillar Games. (see P29) means about five. There is your chal- Those who saw the review of the TZX All machines are now back in their lenge. Duino in episode 76, and my subse- cases and working fine ready for some quent tweet will know I found that this The old school magazines had many filming for the next few episodes. -

Provenance of Kiseru in an Ainu Burial at the Iruekashi Site, Hokkaido

Cultural contact and trade between the Ainu and Japanese prior to 1667: Provenance of kiseru in an Ainu burial at the Iruekashi site, Hokkaido FU K ASAWA Yuriko1 ABSTRACT Focusing on the production and circulation of kiseru (Japanese smoking devices), the aim of this paper is to discuss cultural contact and trade between the Ainu and Japanese in the 17th century. The archaeological discovery of several examples of kiseru, at the Iruekashi site including an Ainu burial that predates 1667, implies that these artefacts were diffused to Ainu by as early as the first half of the 17th century. Furthermore, results of a comparative chronological study on the morphological characteristics of artefacts suggest that they most likely originated from Kyoto. Ethnographic and historical sources have elucidated a long history of the production of such handicrafts in Kyoto, where metal materials were manufactured at specialized workshops concentrated in a specific area. Data from historical documents and archaeological excavations have also revealed how processes of technological production have changed over time. Finally, the results of this study indicate that a marine trade route connecting western Japan and Hokkaido along the cost of the Japan Sea was already in use by the middle of the 17th Century, before the establishment of the Kitamaebune trade route to the North. KEYWORDS: kiseru, smoking device, Ainu, Iruekashi site, Kyoto handicrafts, 1667 Introduction All over the world, the presence of devices for smoking including kiseru, European and clay pipes are significant in an archaeological context in order to understand cultural contact, trade, and the diffusion of cultural commodities. -

Deepwater Archaeology Off Tobishima Island of Northern Japan

Deepwater Archaeology off Tobishima Island of Northern Japan Hayato Kondo1 and Akifumi Iwabuchi2 Abstract Tobishima island on the Japan sea, belonging to Yamagata prefecture, lies about 40 kilometres to the northwest of mainland Japan. Although the island itself is relatively small, it has been on seaborne trading routes since ancient times. Trawl fishermen occasionally find earthenware pots of the 8th century by accident around the seabed. From the late 17th to the 19th centuries Tobishima island was an important islet of call for Kitamaebune, which were wooden cargo ships trading along the northern coast of Japan. According to local legends, the southeastern waters just in front of the main port is a kind of ships’ graveyard hallowed by sacred memories. Contrariwise, no reliable historical record on maritime disasters or shipwrecks exists. In February 2011 Tokyo University of Marine Science & Technology (TUMSAT) and the Asian Research Institute of Underwater Archaeology (ARIUA) conducted the preliminary submerged survey around these waters, utilising a multibeam sonar system and a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV). The research team succeeded in recording fine-resolution bathymetries and video images of a few shipwrecks lying between 60 and 85 metres. One looks modern, but one seems to be potentially older. For the next step, an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV), which has been designed and developed by TUMSAT, is planned to be employed for the visual mappings. The AUV is able to hover for observation by approaching very close to specified objects, and is equipped with high definition cameras. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional photo mosaics will be obtained, while accurate bathymetry data shall be recorded using sonar and an optical ranging system mounted on the vehicle in order to creat fully-covered and detailed site plans. -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts. -

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism STEVEN HEINE DALE S. WRIGHT, Editors OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Zen Classics This page intentionally left blank Zen Classics Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism edited by steven heine and dale s. wright 1 2006 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright ᭧ 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zen classics: formative texts in the history of Zen Buddhism / edited by Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: The concept of classic literature in Zen Buddhism / Dale S. Wright—Guishan jingce and the ethical foundations of Chan practice / Mario Poceski—A Korean contribution to the Zen canon the Oga hae scorui / Charles Muller—Zen Buddhism as the ideology of the Japanese state / Albert Welter—An analysis of Dogen’s Eihei goroku / Steven Heine—“Rules of purity” in Japanese Zen / T. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

What Is Dewa Sanzan? the Spiritual Awe-Inspiring Mountains in the Tohoku Area, Embracing Peopleʼs Prayers… from the Heian Period, Mt.Gassan, Mt.Yudono and Mt

The ancient road of Dewa Rokujurigoegoe Kaido Visit the 1200 year old ancient route! Sea of Japan Yamagata Prefecture Tsuruoka City Rokujurigoe Kaido Nishikawa Town Asahi Tourism Bureau 60-ri Goe Kaido Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture The Ancient Road “Rokujuri-goe Kaido” Over 1200 years, this road has preserved traces of historical events “Rokujuri-goe Kaido,” an ancient road connecting the Shonai plain and the inland area is said to have opened about 1200 years ago. This road was the only road between Shonai and the inland area. It was a precipitous mountain road from Tsuruoka city to Yamagata city passing over Matsune, Juo-toge, Oami, Sainokami-toge, Tamugimata and Oguki-toge, then going through Shizu, Hondoji and Sagae. It is said to have existed already in ancient times, but it is not clear when this road was opened. The oldest theory says that this road was opened as a governmental road connecting the Dewa Kokufu government which was located in Fujishima town (now Tsuruoka city) and the county offices of the Mogami and Okitama areas. But there are many other theories as well. In the Muromachi and Edo periods, which were a time of prosperity for mountain worship, it became a lively road with pilgrims not only from the local area,but also from the Tohoku Part of a list of famous places in Shonai second district during the latter half of the Edo period. and Kanto areas heading to Mt. Yudono as “Oyama mairi” (mountain pilgrimage) custom was (Stored at the Native district museum of Tsuruoka city) booming. -

BEYOND THINKING a Guide to Zen Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK Spiritual practice is not some kind of striving to produce enlightenment, but an expression of the enlightenment already inherent in all things: Such is the Zen teaching of Dogen Zenji (1200–1253) whose profound writings have been studied and revered for more than seven hundred years, influencing practitioners far beyond his native Japan and the Soto school he is credited with founding. In focusing on Dogen’s most practical words of instruction and encouragement for Zen students, this new collection highlights the timelessness of his teaching and shows it to be as applicable to anyone today as it was in the great teacher’s own time. Selections include Dogen’s famous meditation instructions; his advice on the practice of zazen, or sitting meditation; guidelines for community life; and some of his most inspirational talks. Also included are a bibliography and an extensive glossary. DOGEN (1200–1253) is known as the founder of the Japanese Soto Zen sect. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Translators Reb Anderson Edward Brown Norman Fischer Blanche Hartman Taigen Dan Leighton Alan Senauke Kazuaki Tanahashi Katherine Thanas Mel Weitsman Dan Welch Michael Wenger Contributing Translator Philip Whalen BEYOND THINKING A Guide to Zen Meditation Zen Master Dogen Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi Introduction by Norman Fischer SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue -

Giving Birth to a Rich Nation and Strong Soldiers: Midwives and Nation Building in Japan Between the Meiji Period and the 1940S

Giving Birth to a Rich Nation and Strong Soldiers: Midwives and Nation Building in Japan between the Meiji Period and the 1940s. Aya Homei Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine, University of Manchester A paper for the Joint Princeton-Columbia Graduate Student Workshop (National Identity and Public Policy in Comparative Perspective) Princeton, September 29 - October 1, 2000 Introduction In 1916, in the midwifery journal Josan no Shiori Takatsuji published an article titled “Shin-shin no Kaizen wa Kokka Hukyo no Soseki nari (Improvement of spirit and body is a foundation for a rich and strong nation). From the Meiji period onwards Japan had been actively searching for the means to modernize the country, exemplified by the slogan hukoku kyohei (rich nation, strong soldiers). As part of this scheme, western medicine was vigorously examined and implemented in national policies. Simultaneously high mortality and need of human resources for the nationalistic cause (in the emerging industry in the Meiji period and in the sphere of military) made midwives a target for medicalization. Thus once midwives were medicalized through professionalization they were expected to play a central role in making the country fit for war in the industrial age. Especially during the 1930s and 1940s when countless regulations on population issues as well as maternal and infant protection were enacted (and not coincidentally another slogan umeyo huyaseyo, “give birth and multiply,” was promoted), midwives’ role appeared paramountly important. This essay deals with ways in which the birth attendants professionalized and at the same time acted as agents of liaison between the government who attempted to transport the gospel of hygiene (including racial hygiene) and the homes of Japan.