Passing “The Message” in Cape Verde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion Crossing Boundaries Religion and the Social Order

Religion Crossing Boundaries Religion and the Social Order An Offi cial Publication of the Association for the Sociology of Religion General Editor William H. Swatos, Jr. VOLUME 18 Religion Crossing Boundaries Transnational Religious and Social Dynamics in Africa and the New African Diaspora Edited by Afe Adogame and James V. Spickard LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Religion crossing boundaries : transnational religious and social dynamics in Africa and the new African diaspora / edited by Afe Adogame and James V. Spickard. p. cm. -- (Religion and the social order, ISSN 1061-5210 ; v. 18) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-90-04-18730-6 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Blacks--Africa--Religion. 2. Blacks--Religion. 3. African diaspora. 4. Globalization--Religious aspects. I. Adogame, Afeosemime U. (Afeosemime Unuose), 1964- II. Spickard, James V. III. Title. IV. Series. BL2400.R3685 2010 200.89'96--dc22 2010023735 ISSN 1061-5210 ISBN 978 90 04 18730 6 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to Th e Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Cape Verde Islands, C. 1500–1879

TRANSFORMATION OF “OLD” SLAVERY INTO ATLANTIC SLAVERY: CAPE VERDE ISLANDS, C. 1500–1879 By Lumumba Hamilcar Shabaka A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History- Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT TRANSFORMATION OF “OLD” SLAVERY INTO ATLANTIC SLAVERY: CAPE VERDE ISLANDS, C. 1500–1879 By Lumumba Hamilcar Shabaka This dissertation explores how the Atlantic slave trade integrated the Cape Verde archipelago into the cultural, economic, and political milieu of Upper Guinea Coast between 1500 and 1879. The archipelago is about 300 miles off the coast of Senegal, West Africa. The Portuguese colonized the “uninhabited” archipelago in 1460 and soon began trading with the mainland for slaves and black African slaves became the majority, resulting in the first racialized Atlantic slave society. Despite cultural changes, I argue that cultural practices by the lower classes, both slaves and freed slaves, were quintessentially “Guinean.” Regional fashion and dress developed between the archipelago and mainland with adorning and social use of panu (cotton cloth). In particular, I argue Afro-feminine aesthetics developed in the islands by freed black women that had counterparts in the mainland, rather than mere creolization. Moreover, the study explores the social instability in the islands that led to the exile of liberated slaves, slaves, and the poor, the majority of whom were of African descent as part of the Portuguese efforts to organize the Atlantic slave trade in the Upper th Guinea Coast. With the abolition of slavery in Cape Verde in the 19 century, Portugal used freed slaves and the poor as foot soldiers and a labor force to consolidate “Portuguese Guinea.” Many freed slaves resisted this mandatory service. -

List of Maps

List of Maps 1. The Early Africa ........................................................................................ 43 2. Early Christianity in Egypt.. ...................................................................... 74 3. Early Christianity in Nubia ...................................................................... 116 4. European Discovery of Africa between the 1400s and the 1700s .......... .139 5. Early Roman Catholic Missions in West Africa ...................................... 171 6. The Gospel into the Heart of Africa (1790-1890) ................................... 217 7. Early Missions in East Africa .................................................................. 256 8. Early Missions in Southern Africa (1790s-1860s) .................................. 257 9. Principal Locations of African Instituted Churches ................................ 308 10 Contemporary Africa ............................................................................... 515 Digitised by the University of Pretoria, Library Services, 2013 Subjects, Names of Places and People Acts, 48, 49, 50, 76, 85, 232, A 266,298,389,392,422,442, AACC, 283, 356, 359, 360, 365, 537 393,400,449,453,470,487, Acts of the Apostles, 232, 389, 489,491,492 422 Aachen, x Ad Din Abaraha, 106 Salah ad Din, 98 Abdallah Adal, 110 Muhammad Ahmad ibn Adegoke Abdallah, 124 John Adegoke, 507 Abduh Adesius Muhammad Abduh, 133 Sidrakos Adesius, 106 Abdullah Arabs, 100 Abdullah, 128 Ado game Abeng A. Adogame, iv, 312,510 N. Abeng, x Afe Adogame, vi, 37, 41, 309, Abiodun -

La Diffusion Des Plantes Américaines Dans La Région Des Grands Lacs

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 52 | 2019 La diffusion des plantes américaines dans la région des Grands Lacs Approches générale et sous-régionale, l’Ouest kényan Dissemination of the American Plants in the Great Lakes Region: General and Sub-Regional Approaches, the Western Kenya Elizabeth Vignati et Christian Thibon (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/452 Éditeur IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 mars 2019 ISSN : 2071-7245 Référence électronique Elizabeth Vignati et Christian Thibon (dir.), Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review, 52 | 2019, « La diffusion des plantes américaines dans la région des Grands Lacs » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 07 mai 2019, consulté le 25 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/452 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review La diffusion des plantes américaines dans la région des Grands Lacs Approches générale et sous-régionale, l’Ouest kényan Dissemination of the American Plants in the Great Lakes Region General and Sub-Regional Approaches, the Western Kenya 2019 © IFRA 2019 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de 1’Est / The East African Review n° 52, 2019 Chief Editor: Marie-Aude Fouéré Deputy Director: Chloé Josse-Durand Guest Editor: Elizabeth Vignati Editorial secretary: Bastien Miraucourt Cartographer: Valérie Alfaurt Avis L’IFRA n’est pas responsable des prises de position des auteurs. L’objectif des Cahiers est de diffuser des informations sur des travaux de recherche ou documents, sur lesquels le lecteur exercera son esprit critique. -

Ver / Descargar Obra En

1 Los Choques Civilizatorios desde los Orígenes de la Humanidad. Y desde la Caída de Constantinopla al Colapso de las Torres Gemelas (Civilizational Clashes since the Origin of Mankind. And from the Fall of Constantinople to the Twin Towers Collapse) por Eduardo R. Saguier (CONICET-Argentina) Dedicado a mi mujer María Cristina Mendilaharzu, sin cuyo apoyo este trabajo no hubiera sido posible.* Índice--Sumario-Abstract-Keywords I.- Traumas, Grandes Juegos, y Choques Civilizatorios I-a. Teorización de los cambios civilizatorios (Eisenstadt, Kavolis, Lumumba) I-b. El método comparativo en la “larga duración” I-c. Pasajes de dominación histórica y evolucionismo multilineal I-d. Modernizaciones y dominaciones carismáticas y burocráticas II.- Choques civilizatorios, revolución paleolítica, catastrofismo homínido, y neolítico III.- Tercer choque civilizatorio, o sedentarismo vs cataclismo nómade III-a.- Despotismo asiático, mesianismo, y tráfico esclavista oriental IV. Cuarto choque civilizatorio, crisis de modernidad y reparto del mundo (1492-1945) IV-a. Pugna renacentista y belicismo teológico (1492-1776) IV-a-1. Absolutismo de castas y trauma cromático IV-a-2. Anexionismo islámico y trata transoceánica IV-a-3. Expansionismo esclavista occidental y marranismo negrero IV-b. Giro del antiguo régimen a la modernidad iluminista (1776-1890) IV-b-1. Estados-tapones y fronteras fijas y amortiguadoras IV-b-2. Descolonización ilustrada y violencia independentista IV-b-3. Pasaje de las monarquías absolutistas al estado-nación IV-c.- Rivalidad secularizadora y progresismo cientificista (1856-1914) IV-c-1. Secesión secularizadora y guerras separatistas IV-c-2. Secesión territorial de signo positivista IV-c-3. I Guerra Fría o Fashoda (1898) y “Paz armada” (1870-1914) IV-d.- Auto-determinación nacionalista y ciencia moderna en crisis (1919-1945) IV-d-1. -

World Social Report 2021: Reconsidering Rural Development

World Social Report 2021 Reconsidering Rural Development WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2021 Department of Economic and Social Affairs The World Social Report is a flagship publication of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). UN DESA is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department’s mission is to promote and support international cooperation in the pursuit of sustainable development for all. Its work is guided by the universal and transformative 2030 Agenda for Sus- tainable Development, along with a set of 17 integrated Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. UN DESA’s work addresses a range of crosscutting issues that affect peoples’ lives and livelihoods, such as social policy, poverty eradication, employment, social inclusion, inequalities, population, indigenous rights, macroeconomic policy, development finance and cooperation, public sector innovation, forest policy, climate change and sustainable development. United Nations publication Copyright © United Nations, 2021 All rights reserved ST/ESA/376 Sales no.: E.21.IV.2 ISBN: 978-92-1-130424-4 eISBN: 978-92-1-604062-8 Print ISSN: 2664-5467 Online ISSN: 2664-5475 2 FOREWORD Foreword The COVID-19 pandemic has caused immense suffering around the world. It has taken millions of lives, reversed decades of development progress, exacerbated gender inequality and made the task of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 even more difficult. Through response and recovery efforts, however, opportunities exist to build a greener, more inclusive and resilient future. The experience of the pandemic has shown, for example, that where high-quality Internet connectivity is coupled with flexible working arrangements, many jobs that were traditionally considered to be urban can be performed in rural areas too. -

Religion and the State

Religion and the State Religion and the State A Comparative Sociology Edited by Jack Barbalet, Adam Possamai and Bryan S. Turner Anthem Press An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company www.anthempress.com This edition fi rst published in UK and USA 2011 by ANTHEM PRESS 75-76 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK and 244 Madison Ave. #116, New York, NY 10016, USA © 2011 Jack Barbalet, Adam Possamai and Bryan S. Turner editorial matter and selection; individual chapters © individual contributors The moral right of the authors has been asserted. Front cover image © 2011 iStockphoto.com/Cosmonaut All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Religion and the state : a comparative sociology / edited by Jack Barbalet, Adam Possamai, Bryan S. Turner. p. cm. Proceedings of a workshop held July 17–18, 2009 at the University of Western Sydney, Parramatta Campus. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-85728-798-4 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Religion and state–Congresses. I. Barbalet, J. M., 1946- II. Possamai, Adam. III. Turner, Bryan S. BL65.S8R4455 2011 322’.1–dc23 2011039325 ISBN-13: 978 0 85728 798 4 (Hbk) ISBN-10: 0 85728 798 2 (Hbk) This title is also available as an eBook. -

Name Link FR POR SWA Affiliation Time Country Sources Allen, Alfreda ENG Anglican 19Th and Uganda Louise Pirouet (CMS) 20Th Centuries (C

Name Link FR POR SWA Affiliation Time Country Sources Allen, Alfreda ENG Anglican 19th and Uganda Louise Pirouet (CMS) 20th centuries (c. 1875 to 1929) Eshetu Abate ENG Ethiopian 20th-21st Ethiopia Evangelical century Church (1955-2011) Mekane Yesus Kiwavu, Hosua ENG Anglican 19th-20th Uganda Louise Pirouet century (1860?- 1932) Kizza, Tobie ENG Catholic (White 19th-20th Uganda Louise Pirouet Fathers century Mission) (1872(?)- 1961) Lumu, Basil ENG Catholic 19th-20th Uganda Louise Pirouet century (1871-1946) Lwanga, St. ENG Catholic 19th Uganda Louise Pirouet Charles century (c. 1860-1886) Mackay, ENG Catholic 19th-20th Uganda Louise Pirouet Alexander century Morehead (1871-1946) Maddox, Harry ENG Anglican 19th-20th Uganda Louise Pirouet Edward (C.M.S.) century (1871-1951) Name Link FR POR SWA Affiliation Time Country Sources Ababa Bushiro Kale Heywat 20th century Ethiopia Cotterell 148 (Word of Life) Ababius Coptic Church 13th century Egypt Coptic 1, p.1 Abagole Nunemo ENG Kale Heywet 19th-21st Ethiopia Dirshaye Menberu, Ph.D.++ Church century (1894 to 2001) Abamun of Tarnut Ancient Coptic 4th century Egypt Coptic 1, p.1 Church Abamun of Tukh Coptic Church 13th century Egypt Coptic 1, pp.1-2 Abarayama Kenyi Anglican 20th Sudan Rev. Canon Dr. Oliver M. Duku Manasse (Episcopal century (d. ([email protected]), Church of 1986) Bishop Allison Theological Sudan) College; Sources: "Christianity comes to Kajo Keji" by Rev. Dr. Oliver Duku Abayomi-Cole, ENG Wesleyan 19th-20th Sierra Leone EADAB 2 John Augustus& Methodist/ century Cabbalist/ -

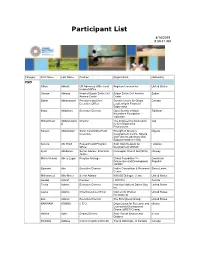

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2021 7:38:33 PM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Babak Abbaszadeh President And Chief Toronto Centre For Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership In Financial Supervision Ziad Abdel Samad Executive Director Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development Tazi Abdelilah Président Associaion Talassemtane pour Morocco l'environnement et le développement ATED Dr. Ghada Abdelsalam Senior Tax manager Egyptian Tax Authority Egypt Ziad ABDELTAWA Deputy Director Cairo institute for Human Egypt B Rights Studies (CIHRS) Sadak Abdi Fishery Development Hifcon Somalia Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Diam Abou Diab Senior program and Arab NGO Network for Lebanon research officer Development Hayk Abrahamyan Community Organizer for International Accountability Armenia South Caucasus and Project Central Asia Barbara Adams Board Chair Global Policy Forum Canada Ben Adams Senior Advisor Mental CBM Global Ireland Health Abiodun Aderibigbe Head of Research and sustainable Environment Food Nigeria project Development and Agriculture Initiative Bamisope Adeyanju Policy Fellow Accountability Counsel Nigeria Mange Adhana President Association For Promotion India Sustainable development Ezatullah Adib Head of Research Integrity Watch Afghanistan Afghanistan Mirna Adjami Program Manager DCAF - Geneva Centre for Switzerland Security Sector Governance Tity Agbahey Africa Regional Coordinator Coalition -

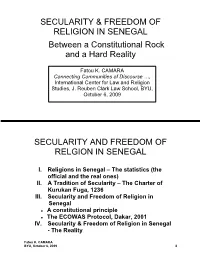

The Charter of Kurukan Fuga, 1236 III. Secularity and Freedom of Religion in Senegal ● a Constitutional Principle ● the ECOWAS Protocol, Dakar, 2001 IV

SECULARITY & FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN SENEGAL Between a Constitutional Rock and a Hard Reality Fatou K. CAMARA Connecting Communities of Discourse …, International Center for Law and Religion Studies, J. Reuben Clark Law School, BYU, October 6, 2009 SECULARITY AND FREEDOM OF RELGION IN SENEGAL I. Religions in Senegal – The statistics (the official and the real ones) II. A Tradition of Secularity – The Charter of Kurukan Fuga, 1236 III. Secularity and Freedom of Religion in Senegal ● A constitutional principle ● The ECOWAS Protocol, Dakar, 2001 IV. Secularity & Freedom of Religion in Senegal - The Reality Fatou K. CAMARA BYU, October 6, 2009 2 Religions in Senegal The statistics (official one and real one) ● Muslim 94% ● Christian 5% (mostly Roman Catholic) ● Indigenous beliefs 1% ● N.B. (caveat) Indigenous faith still shapes the spiritual beliefs of the majority of Senegalese people. Fatou K. CAMARA 3 BYU, October 6, 2009 Religions in Senegal The statistics (official one and real one) ● Senegal‟s first president, the famed poet L.S. Senghor, who was a Catholic raised by missionaries, testified about the continued existence of indigenous faith in both Christian and Muslim men African men and women. Fatou K. CAMARA 4 BYU, October 6, 2009 Religions in Senegal The statistics (official one and real one) ● As today a Moslem Head of State will consult the “sacred wood”, and offer in sacrifice an ox or a bull, I have seen a Christian woman, a practicing medical doctor, consult the sereer “Pangool” (the snakes of the sacred wood). In truth, everywhere in Black Africa, the “revealed” religions” are rooted in the animism which still inspires poets and artists, I am well placed to know it and to say it … (Senghor, Preface, Les Africains, Pierre Alexandre, Lidis, Paris, 1982, p. -

ECFG-Senegal-May-19.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to help prepare you for deployment to culturally complex environments and successfully achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information it contains will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain necessary skills to achieve mission success (Photo a courtesy of the United Nations). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1: Introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2: Presents “Culture Specific” Senegal Senegal, focusing on unique cultural features of Senegalese society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL GENERAL CULTURE What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana