Final Report: Regional Program for the Management of Aquatic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Other Contributions

Other Contributions NATURE NOTES Amphibia: Caudata Ambystoma ordinarium. Predation by a Black-necked Gartersnake (Thamnophis cyrtopsis). The Michoacán Stream Salamander (Ambystoma ordinarium) is a facultatively paedomorphic ambystomatid species. Paedomorphic adults and larvae are found in montane streams, while metamorphic adults are terrestrial, remaining near natal streams (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). Streams inhabited by this species are immersed in pine, pine-oak, and fir for- ests in the central part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Luna-Vega et al., 2007). All known localities where A. ordinarium has been recorded are situated between the vicinity of Lake Patzcuaro in the north-central portion of the state of Michoacan and Tianguistenco in the western part of the state of México (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). This species is considered Endangered by the IUCN (IUCN, 2015), is protected by the government of Mexico, under the category Pr (special protection) (AmphibiaWeb; accessed 1April 2016), and Wilson et al. (2013) scored it at the upper end of the medium vulnerability level. Data available on the life history and biology of A. ordinarium is restricted to the species description (Taylor, 1940), distribution (Shaffer, 1984; Anderson and Worthington, 1971), diet composition (Alvarado-Díaz et al., 2002), phylogeny (Weisrock et al., 2006) and the effect of habitat quality on diet diversity (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). We did not find predation records on this species in the literature, and in this note we present information on a predation attack on an adult neotenic A. ordinarium by a Thamnophis cyrtopsis. On 13 July 2010 at 1300 h, while conducting an ecological study of A. -

Miskito Cays Honduras

Honduras’ MiskitoText and photos by George Stoyle Cays 49 X-RAY MAG : 59 : 2014 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO Diver swims along the edge of a reef covered Miskito Cays travel in marine life, Miskito Cays, Honduras PREVIOUS PAGE: Rope sponges cling to a boulder Following six flights, two nights and a 30-hour boat trip, I found myself approaching a relatively uncharted group of small coral cays about 60km off the northeast coast of Honduras, not far from the Nicaraguan border. I joined a group of scien- tists from various institutions around the world, assigned to document their activities and photograph the habi- tats and associated wildlife both above and below the water. Embarking on the Caribbean Pearl II from Utila, one of the Bay Islands a few miles off the north coast of Honduras, we made our way along the coast to an area unknown to the region’s tour- ist diving operations. As we got close to the cays, our crew grew increasingly nervous, perhaps jus- tifiably so. This part of Honduras has long been a major route for cocaine trafficking into the United States from South America, and the region through which we were sailing was well-known for its use were boarded ourselves by five The archipelago islands and sand bars are dis- inhabit communities along the the blood-sucking insects) La by certain cartels who preferred soldiers armed to the teeth, car- The Miskito Cays form an archi- persed across 750 squ km of shal- coast of both countries. -

A~ ~CMI $~Fttl' G//,-L1 , Date L~-Co-'Fv It.-Lip/I 'L V 12-11 ~ 9T

,\)..lrS A.J.D. EVALUATION SUMMARY - PART I IDENTIFICATION DATA 't~ A. Reporting A.J.D. Unit: B. Was Evaluation Scheduled in Current C. Evaluation Timing USAID/NICARAGUA FY Annual Evaluation Plan? Yes .lL Slipped _ Ad Hoc - Interim .x.. Final_ Evaluation Number:96/3 Evaluation Plan Submission Date: FY: 95 0:2 Ex Post - Other _ D. Activity or Activities Evaluated (List the following information for projectls) or program(s}; if not applicable list title and date of the evaluation report.) Project No. Project/Program Title First PROAG Most Recent Planned LOP Amount or Equivalent PACD Cost {OOOI Obligated to (FY) (mo/yrl date (000) 524-Q.3-l-&- ~,~ Natural Resource Management Project (NRM) 1991 9/99 12,053 10,032 ACTIONS* E. As part of our ongoing refocusing and improved project implementation, we have agreed upon the following actions: 1- The new implementation strategy includes a strong emphasis on buffer zone activities, to be implemented under new, specialized TA. 2- The new implementation strategy will include TA for MARENA to develop an implementation strategy at the national level for the National Protected Areas System (SINAP). 3- Mission contracted with GreenCom to do environmental education activities with Division of Protected Areas (delivery order effective 511 5/96) 4 - Management plans have now been completed for Miskito Cays (CCC), and field work with indigenous communities is near completion for Bosawas. An operational plan has been completed for Volcan Masaya National Park. 5- Mission has no plan to significantly increase number of institutions receiving USAID assistance. Protected Area staff are being placed near field sites as logistics permit. -

Financing Plan, Which Is the Origin of This Proposal

PROJECT DEVELOPMENT FACILITY REQUEST FOR PIPELINE ENTRY AND PDF-B APPROVAL AGENCY’S PROJECT ID: RS-X1006 FINANCINGIDB PDF* PLANIndicate CO-FINANCING (US$)approval 400,000date ( estimatedof PDFA ) ** If supplemental, indicate amount and date GEFSEC PROJECT ID: GEFNational ALLOCATION Contribution 60,000 of originally approved PDF COUNTRY: Costa Rica and Panama ProjectOthers (estimated) 3,000,000 PROJECT TITLE: Integrated Ecosystem Management of ProjectSub-Total Co-financing PDF Co- 960,000 the Binational Sixaola River Basin (estimated)financing: 8,500,000 GEF AGENCY: IDB Total PDF Project 960,000 OTHER EXECUTING AGENCY(IES): Financing:PDF A* DURATION: 8 months PDF B** (estimated) 500,000 GEF FOCAL AREA: Biodiversity PDF C GEF OPERATIONAL PROGRAM: OP12 Sub-Total GEF PDF 500,000 GEF STRATEGIC PRIORITY: BD-1, BD-2, IW-1, IW-3, EM-1 ESTIMATED STARTING DATE: January 2005 ESTIMATED WP ENTRY DATE: January 2006 PIPELINE ENTRY DATE: November 2004 RECORD OF ENDORSEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: Ricardo Ulate, GEF Operational Focal Point, 02/27/04 Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE), Costa Rica Ricardo Anguizola, General Administrator of the 01/13/04 National Environment Authority (ANAM), Panama This proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review Criteria for approval. IA/ExA Coordinator Henrik Franklin Janine Ferretti Project Contact Person Date: November 8, 2004 Tel. and email: 202-623-2010 1 [email protected] PART I - PROJECT CONCEPT A - SUMMARY The bi-national Sixaola river basin has an area of 2,843.3 km2, 19% of which are in Panama and 81% in Costa Rica. -

World Bank Document

The Norwegian Trust Fund for Private Sector and Infrastructure (NTFPSI) Grant TF093075 - P114019: Central America. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Infrastructure and Small Scale Private Sector Development for Coastal Cities of Honduras and Nicaragua – Supporting Responsible Tourism Strategies for Poverty Reduction FIRST PHASE Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report Consulting Team: Walter Bodden Liesbeth Castro-Sierra Mary Elizabeth Flores Armando Frías Italo Mazzei Alvaro Rivera Irma Urquía Lucy Valenti César Zaldívar The George Washington University: Carla Campos Christian Hailer Jessie McComb Elizabeth Weber January 2010 1 y Final Report Infrastructure and Small Scale Private Sector Development for Coastal Cities of Honduras and Nicaragua – Supporting Responsible Tourism Strategies for Poverty Reduction First Phase Table of Contents 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 2 OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................................................. 9 3 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................ 10 4 HONDURAN COASTAL CITIES OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................. -

United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, 1958, Volume I, Preparatory Documents

United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea Geneva, Switzerland 24 February to 27 April 1958 Document: A/CONF.13/15 A Brief Geographical and Hydro Graphical Study of Bays and Estuaries the Coasts of which Belong to Different States Extract from the Official Records of the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Volume I (Preparatory Documents) Copyright © United Nations 2009 Document A/CONF.13/15 A BRIEF GEOGRAPHICAL AND HYDRO GRAPHICAL STUDY OF BAYS AND ESTUARIES THE COASTS OF WHICH BELONG TO DIFFERENT STATES BY COMMANDER R. H. KENNEDY (Preparatory document No. 12) * [Original text: English] [13 November 1957] CONTENTS Page Page INTRODUCTION 198 2. Shatt al-Arab 209 I. AFRICA 3. Khor Abdullah 209 1. Waterway at 11° N. ; 15° W. (approx.) between 4. The Sunderbans (Hariabhanga and Raimangal French Guinea and Portuguese Guinea ... 199 Rivers) 209 2. Estuary of the Kunene River 199 5. Sir Creek 210 3. Estuary of the Kolente or Great Skarcies River 200 6. Naaf River 210 4. The mouth of the Manna or Mano River . 200 7. Estuary of the Pakchan River 210 5. Tana River 200 8. Sibuko Bay 211 6. Cavally River 200 IV. CHINA 7. Estuary of the Rio Muni 200 1. The Hong Kong Area 212 8. Estuary of the Congo River 201 (a) Deep Bay 212 9. Mouth of the Orange River 201 (b) Mirs Bay 212 II. AMERICA (c) The Macao Area 213 1. Passamaquoddy Bay 201 2. Yalu River 213 2. Gulf of Honduras 202 3. Mouth of the Tyumen River 214 3. -

Marine Turtle Newsletter Issue Number 160 January 2020

Marine Turtle Newsletter Issue Number 160 January 2020 A female olive ridley returns to the sea in the early light of dawn after nesting in the Gulf of Fonseca, Honduras. See pages 1-4. Photo by Stephen G. Dunbar Articles Marine Turtle Species of Pacific Honduras..................................................................................................SG Dunbar et al. A Juvenile Green Turtle Long Distance Migration in the Western Indian Ocean.........................................C Sanchez et al. Nesting activity of Chelonia mydas and Eretmochelys imbricata at Pom-Pom Island, Sabah, Malaysia.....O Micgliaccio et al. First Report of Herpestes ichneumon Predation on Chelonia mydas Hatchlings in Turkey............................AH Uçar et al. High Number of Healthy Albino Green Turtles from Africa’s Largest Population...................................FM Madeira et al. Hawksbill Turtle Tagged as a Juvenile in Cuba Observed Nesting in Barbados 14 Years Later..................F Moncada et al. Recent Publications Announcement Reviewer Acknowledgements Marine Turtle Newsletter No. 160, 2020 - Page 1 ISSN 0839-7708 Editors: Managing Editor: Kelly R. Stewart Matthew H. Godfrey Michael S. Coyne The Ocean Foundation NC Sea Turtle Project SEATURTLE.ORG c/o Marine Mammal and Turtle Division NC Wildlife Resources Commission 1 Southampton Place Southwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA-NMFS 1507 Ann St. Durham, NC 27705, USA 8901 La Jolla Shores Dr. Beaufort, NC 28516 USA E-mail: [email protected] La Jolla, California 92037 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 919 684-8741 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 858-546-7003 On-line Assistant: ALan F. Rees University of Exeter in Cornwall, UK Editorial Board: Brendan J. Godley & Annette C. Broderick (Editors Emeriti) Nicolas J. -

50 Archaeological Salvage at El Chiquirín, Gulf Of

50 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SALVAGE AT EL CHIQUIRÍN, GULF OF FONSECA, LA UNIÓN, EL SALVADOR Marlon Escamilla Shione Shibata Keywords: Maya archaeology, El Salvador, Gulf of Fonseca, shell gatherers, Salvage archaeology, Pacific Coast, burials The salvage archaeological investigation at the site of El Chiquirín in the department of La Unión was carried out as a consequence of an accidental finding made by local fishermen in November, 2002. An enthusiast fisherman from La Unión –José Odilio Benítez- decided, like many other fellow countrymen, to illegally migrate to the United States in the search of a better future for him and his large family. His major goal was to work and save money to build a decent house. Thus, in September 2002, just upon his arrival in El Salvador, he initiated the construction of his home in the village of El Chiquirín, canton Agua Caliente, department of La Unión, in the banks of the Gulf of Fonseca. By the end of November of the same year, while excavating for the construction of a septic tank, different archaeological materials came to light, including malacologic, ceramic and bone remains. The finding was much surprising for the community of fishermen, the Mayor of La Unión and the media, who gave the finding a wide cover. It was through the written press that the Archaeology Unit of the National Council for Culture and Art (CONCULTURA) heard about the discovery. Therefore, the Archaeology Unit conducted an archaeological inspection at that residential place, to ascertain that the finding was in fact a prehispanic shell deposit found in the house patio, approximately 150 m away from the beach. -

Earthquake-Induced Landslides in Central America

Engineering Geology 63 (2002) 189–220 www.elsevier.com/locate/enggeo Earthquake-induced landslides in Central America Julian J. Bommer a,*, Carlos E. Rodrı´guez b,1 aDepartment of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine, Imperial College Road, London SW7 2BU, UK bFacultad de Ingenierı´a, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Santafe´ de Bogota´, Colombia Received 30 August 2000; accepted 18 June 2001 Abstract Central America is a region of high seismic activity and the impact of destructive earthquakes is often aggravated by the triggering of landslides. Data are presented for earthquake-triggered landslides in the region and their characteristics are compared with global relationships between the area of landsliding and earthquake magnitude. We find that the areas affected by landslides are similar to other parts of the world but in certain parts of Central America, the numbers of slides are disproportionate for the size of the earthquakes. We also find that there are important differences between the characteristics of landslides in different parts of the Central American isthmus, soil falls and slides in steep slopes in volcanic soils predominate in Guatemala and El Salvador, whereas extensive translational slides in lateritic soils on large slopes are the principal hazard in Costa Rica and Panama. Methods for assessing landslide hazards, considering both rainfall and earthquakes as triggering mechanisms, developed in Costa Rica appear not to be suitable for direct application in the northern countries of the isthmus, for which modified approaches are required. D 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Landslides; Earthquakes; Central America; Landslide hazard assessment; Volcanic soils 1. -

United Nations Development Programme Project Title

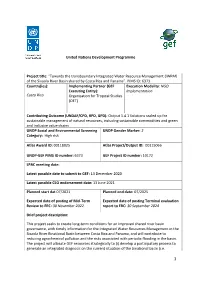

ƑPROJECT INDICATOR 10 United Nations Development Programme Project title: “Towards the transboundary Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) of the Sixaola River Basin shared by Costa Rica and Panama”. PIMS ID: 6373 Country(ies): Implementing Partner (GEF Execution Modality: NGO Executing Entity): Implementation Costa Rica Organisation for Tropical Studies (OET) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Output 1.4.1 Solutions scaled up for sustainable management of natural resources, including sustainable commodities and green and inclusive value chains UNDP Social and Environmental Screening UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Category: High risk Atlas Award ID: 00118025 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00115066 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6373 GEF Project ID number: 10172 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 13 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 13 June 2021 Planned start dat 07/2021 Planned end date: 07/2025 Expected date of posting of Mid-Term Expected date of posting Terminal evaluation Review to ERC: 30 November 2022. report to ERC: 30 September 2024 Brief project description: This project seeks to create long-term conditions for an improved shared river basin governance, with timely information for the Integrated Water Resources Management in the Sixaola River Binational Basin between Costa Rica and Panama, and will contribute to reducing agrochemical pollution and the risks associated with periodic flooding in the basin. The project will allocate GEF resources strategically to (i) develop a participatory process to generate an integrated diagnosis on the current situation of the binational basin (i.e. 1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis - TDA) and a formal binding instrument adopted by both countries (i.e. -

Economic Values of the World's Wetlands

Living Waters Conserving the source of life The Economic Values of the World’s Wetlands Prepared with support from the Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape (SAEFL) Gland/Amsterdam, January 2004 Kirsten Schuyt WWF-International Gland, Switzerland Luke Brander Institute for Environmental Studies Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands Table of Contents 4 Summary 7 Introduction 8 Economic Values of the World’s Wetlands 8 What are Wetlands? 9 Functions and Values of Wetlands 11 Economic Values 15 Global Economic Values 19 Status Summary of Global Wetlands 19 Major Threats to Wetlands 23 Current Situation, Future Prospects and the Importance of Ramsar Convention 25 Conclusions and Recommendations 27 References 28 Appendix 1: Wetland Sites Used in the Meta-Analysis 28 List of 89 Wetland Sites 29 Map of 89 Wetland Sites 30 Appendix 2: Summary of Methodology 30 Economic Valuation of Ecosystems 30 Meta-analysis of Wetland Values and Value Transfer Left: Water lilies in the Kaw-Roura Nature Reserve, French Guyana. These wetlands were declared a nature reserve in 1998, and cover area of 100,000 hectares. Kaw-Roura is also a Ramsar site. 23 ©WWF-Canon/Roger LeGUEN Summary Wetlands are ecosystems that provide numerous goods and services that have an economic value, not only to the local population living in its periphery but also to communities living outside the wetland area. They are important sources for food, fresh water and building materials and provide valuable services such as water treatmentSum and erosion control. The estimates in this paper show, for example, that unvegetated sediment wetlands like the Dutch Wadden Sea and the Rufiji Delta in Tanzania have the highest median economic values of all wetland types at $374 per hectare per year. -

Solentiname-Tours-Brochure.Pdf

Located in the heart of the Central American isthmus, Nicaragua is the land bridge Welcome between North and South America. It separates the Pacific Ocean from the Caribbean to Nicaragua Sea. The bellybutton of America is unique, due to its almost virgin land. Our republic is being rediscovered as a key part of a wonderful natural world. Nicaragua's great cul- ture and history have much to offer. This unique stretch of land offers a variety of trop- ical fruits unknown to the rest of the world, one of the largest lake of the world and many biological reserves and nature parks with their native plant and animal species. We invite you to experience this extraordinary culture and exceptional natural beauty among the most amiable people on earth. Our team of experts in alternative and sus- tainable tourism specializes in organizing unique lifetime experience for your clients. Each tour package reflects their interests, personal needs, and budget. Flexibility and creativity allow us to design programs for individuals, retired or student groups, suggest multiple package options, or recommend an exclusive itinerary with private plans and deluxe accommodations. We have best specialist Ecological, Culture, Adventure and Incentive Programs. You and your clients remain confident that all is taken care of when Solentiname Tours makes the arrangements. We are pleased to work with you. We invite you to review this manual and contact us for specific suggestions and additional information. Immanuel Zerger Owner and General Director First Stop Managua,