The Two Sterling Crises of 1964

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussing What Prime Ministers Are For

Discussing what Prime Ministers are for PETER HENNESSY New Labour has a lot to answer for on this front. They On 13 October 2014, Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield FBA, had seen what the press was doing to John Major from Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History at Queen Black Wednesday onwards – relentless attacks on him, Mary, University of London, delivered the first British which bothered him deeply.1 And they were determined Academy Lecture in Politics and Government, on ‘What that this wouldn’t happen to them. So they went into are Prime Ministers for?’ A video recording of the lecture the business of creating permanent rebuttal capabilities. and an article published in the Journal of the British Academy If somebody said something offensive about the can be found via www.britishacademy.ac.uk/events/2014/ Government on the Today programme, they would make every effort to put it right by the World at One. They went The following article contains edited extracts from the into this kind of mania of permanent rebuttal, which question and answer session that followed the lecture. means that you don’t have time to reflect before reacting to events. It’s arguable now that, if the Government doesn’t Do we expect Prime Ministers to do too much? react to events immediately, other people’s versions of breaking stories (circulating through social media etc.) I think it was 1977 when the Procedure Committee in will make the pace, and it won’t be able to get back on the House of Commons wanted the Prime Minister to be top of an issue. -

Plutocracy: the Marketising of ‘Equality’ Within Neoliberalism

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Littler, J. (2013). Meritocracy as plutocracy: the marketising of ‘equality’ within neoliberalism. New Formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, 80-81, pp. 52-72. doi: 10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/4167/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MERITOCRACY AS PLUTOCRACY: THE MARKETISING OF ‘EQUALITY’ UNDER NEOLIBERALISM Jo Littler Abstract Meritocracy, in contemporary parlance, refers to the idea that whatever our social position at birth, society ought to facilitate the means for ‘talent’ to ‘rise to the top’. This article argues that the ideology of ‘meritocracy’ has become a key means through which plutocracy is endorsed by stealth within contemporary neoliberal culture. -

Download Book (PDF)

01-Titelei.Buch : 01-Titelei 1 11-05-19 13:21:24 -po1- Benutzer fuer PageOne Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Historischen Instituts London Publications of the German Historical Institute London 01-Titelei.Buch : 01-Titelei 2 11-05-19 13:21:25 -po1- Benutzer fuer PageOne Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Historischen Instituts London Herausgegeben von Hagen Schulze Band 53 Publications of the German Historical Institute London Edited by Hagen Schulze Volume 53 R. Oldenbourg Verlag München 2002 01-Titelei.Buch : 01-Titelei 3 11-05-19 13:21:25 -po1- Benutzer fuer PageOne Dominik Geppert Thatchers konservative Revolution Der Richtungswandel der britischen Tories 1975–1979 R. Oldenbourg Verlag München 2002 01-Titelei.Buch : 01-Titelei 4 11-05-19 13:21:25 -po1- Benutzer fuer PageOne Meinen Eltern Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Geppert, Dominik: Thatchers konservative Revolution : der Richtungswandel der britischen Tories 1975 - 1979 / Dominik Geppert. - München : Oldenbourg, 2002 (Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Historischen Instituts London ; Bd. 53) Zugl.: Berlin, Freie Univ., Diss., 2000 ISBN 3-486-56661-X © 2002 Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, München Rosenheimer Straße 145, D - 81671 München Internet: http://www.oldenbourg-verlag.de Das Werk einschließlich aller Abbildungen ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Ver- wertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Über- setzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Bearbeitung in elektroni- schen Systemen. Umschlaggestaltung: Dieter Vollendorf, München Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (chlorfrei gebleicht). Gesamtherstellung: R. Oldenbourg Graphische Betriebe Druckerei GmbH, München ISBN 3-486-56661-X 01-Titelei.Buch : 02-Inhalt 5 11-05-19 13:21:25 -po1- Benutzer fuer PageOne Inhalt 5 INHALT EINLEITUNG............................... -

The Role of HM Embassy in Washington

The Role of HM Embassy in Washington edited by Gillian Staerck and Michael D. Kandiah ICBH Witness Seminar Programme The Role of HM Embassy in Washington ICBH Witness Seminar Programme Programme Director: Dr Michael D. Kandiah © Institute of Contemporary British History, 2002 All rights reserved. This material is made available for use for personal research and study. We give per- mission for the entire files to be downloaded to your computer for such personal use only. For reproduction or further distribution of all or part of the file (except as constitutes fair dealing), permission must be sought from ICBH. Published by Institute of Contemporary British History Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study University of London Malet St London WC1E 7HU ISBN: 1 871348 83 8 The Role of HM Embassy in Washington Held 18 June 1997 in the Map Room, Foreign & Commonwealth Office Chaired by Lord Wright of Richmond Seminar edited by Gillian Staerck and Michael D. Kandiah Institute of Contemporary British History Contents Contributors 9 Citation Guidance 11 The Role of HM Embassy in Washington 13 edited by Gillian Staerck and Michael D. Kandiah Contributors Editors: GILLIAN STAERCK Institute of Contemporary British History DR MICHAEL KANDIAH Institute of Contemporary British History Chair: LORD WRIGHT OF Private Secretary to Ambassador and later First Secretary, Brit- RICHMOND ish Embassy, Washington 1960-65, and Permanent Under-Sec- retary and Head of Diplomatic Service, FCO 1986-91. Paper-giver DR MICHAEL F HOPKINS Liverpool Hope University College. Witnesses: SIR ANTONY ACLAND GCMG, GCVO. British Ambassador, Washington 1986-91. PROFESSOR KATHLEEN University College, University of London. -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

The Da Vinci Delusion Unions—Their Great Failure What's Wrong With

middle class and broke: new polls issue 208 | july 2013 www.prospect-magazine.co.uk july 2013 | £4.50 Britain’s folly in Syria britain’s folly in syria Plus The Da Vinci delusion CliVe James Unions—their great failure DaViD gooDharT What’s wrong with France? ChrisTine oCkrenT We’re all machiavelli now JonaThan poWell poet of postwar Britain JonaThan Coe True cost of eU exit: richard lambert In 1912 Malcolm Campbell christened his car “Blue Bird” and a legend was born. More than 100 years later this iconic marque continues to challenge for world speed records using futuristic electric vehicles. Christopher Ward is proud to be the Official Timing Partner for Bluebird and, to celebrate our partnership we have released this exceptional timepiece in a limited edition of 1,912 pieces. 174_ChristopherWard_Prospect.indd 1 10/06/2013 08:16 174_ChristopherWard_Prospect.indd 2 10/06/2013 08:16 We explore further. Aberdeen Investment Trusts ISA and Share Plan At Aberdeen, we believe there’s no substitute for getting to know your investments face-to-face. That’s why we make it our goal to visit companies – wherever they are – before we ever invest in their shares and again when we hold them. With 17 investment companies investing around the world – that’s an awfully big commitment. But it’s just one of the ways we aim to seek out the best investment opportunities on your behalf. Please remember, the value of shares and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may get back less than the amount invested. -

1 Recapturing Labour's Traditions? History, Nostalgia and the Re-Writing

Recapturing Labour’s Traditions? History, nostalgia and the re-writing of Clause IV Dr Emily Robinson University of Nottingham The making of New Labour has received a great deal of critical attention, much of which has inevitably focused on the way in which it placed itself in relation to past and future, its inheritances and its iconoclasm.1 Nick Randall is right to note that students of New Labour have been particularly interested in ‘questions of temporality’ because ‘New Labour so boldly advanced a claim to disrupt historical continuity’.2 But it is not only academics who have contributed to this analysis. Many of the key figures associated with New Labour have also had their say. The New Labour project was not just about ‘making history’ in terms of its practical actions; the writing up of that history seems to have been just as important. As early as 1995 Peter Mandelson and Roger Liddle were preparing a key text designed ‘to enable everyone to understand better why Labour changed and what it has changed into’.3 This was followed in 1999 by Phillip Gould’s analysis of The Unfinished Revolution: How the Modernisers Saved the Labour Party, which motivated Dianne Hayter to begin a PhD in order to counteract the emerging consensus that the modernisation process began with the appointment of Gould and Mandelson in 1983. The result of this study was published in 2005 under the title Fightback! Labour’s Traditional Right in the 1970s and 1980s and made the case for a much longer process of modernisation, strongly tied to the trade unions. -

Transcript of Interview with David Kynaston (Historian)

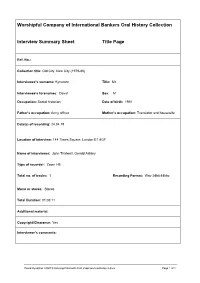

Worshipful Company of International Bankers Oral History Collection Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref. No.: Collection title: Old City, New City (1979-86) Interviewee’s surname: Kynaston Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: David Sex: M Occupation: Social historian Date of birth: 1951 Father’s occupation: Army officer Mother’s occupation: Translator and housewife Date(s) of recording: 24.04.19 Location of interview: 144 Times Square, London E1 8GF Name of interviewer: John Thirlwell, Gerald Ashley Type of recorder: Zoom H5 Total no. of tracks: 1 Recording Format: Wav 24bit 48khz Mono or stereo: Stereo Total Duration: 01:03:11 Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Yes Interviewer’s comments: David Kynaston 240419 transcript final with front sheet and endnotes-3.docx Page 1 of 1 Introduction and biography #00:00:00# A club no more: changes from the pre-1980’s village; the #00:0##### aluminium war; Lord Cobbold #00:07:36# Factors of change and external pressures; effects of the abolition of Exchange Control; minimum commissions and single and dual capacity The Stock Exchange ownership question; opening ip to #00:12:17# foreign competition; silly prices paid for firms Cazenove & Co – John Kemp-Welch on partnership and #00:14:57# trust; US capital; Cazenove capital raising Motivations of Big Bang; Philips & Drew; John Craven and #00:18:22# ‘top dollar’ Lloyd’s of London #00:22:26# Bank of England; Margaret Thatcher’s view of the City and #00:25:07# vice versa and her relationship with the Governor, Lord Cobbold Robin Leigh-Pemberton -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Tribune, December 3, 1943, in Paul Anderson ed. Orwell in Tribune (London: Politico’s, 2006), 57. 2. Margaret Tapster, WW2 People’s War, an online archive of wartime memories con- tributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/ 65/a5827665.shtml Accessed May 30, 2013. 3. Paul Addison, No Turning Back: The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); Peter Hennessy, Having It So Good: Britain in the Fifties (London: Allen Lane, 2006); David Kynaston Aus- terity Britain, 1945–51 (London, Berlin and New York: Bloomsbury, 2007); David Kynaston, Family Britain, 1951–1957 (London, Berlin, New York: Bloomsbury, 2009); Mark Donnelly, Sixties Britain: Culture, Society and Politics (Harlow: Pearson, 2005); Alwyn W. Turner, Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s (London: Aurum Press, 2008); Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber and Faber, 2009); Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979 (London: Allen Lane, 2012); Alwyn W. Turner, Rejoice! Rejoice! Britain in the 1980s (London: Aurum, 2010) and Andy McSmith, No Such Thing as Society: A History of Britain in the 1980s (London: Constable, 2011). 4. British and European resistance to American culture is expounded by Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London and New York: Routledge, 1979); Rob Kroes et al. Cultural Transmissions and Receptions: American Mass Culture in Europe (Amsterdam: VU University Press, 1993) and Rob Kroes, If You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen the Mall: Europeans and American Mass Culture (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996). -

46 Spring 2005.Indd

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 46 / Spring 2005 / £5.00 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y Liberals and the land Roy Douglas Land taxing and the Liberals, 1879 – 1914 Hans-Joachim Heller Sir Edward Grey’s German love-child Anne Newman Dundee’s grand old man Biography of Edmund Robertson MP Ian Ivatt Frances Stevenson, Lloyd George and the Surrey – Sussex dimension Brenda Tillotson and Ian Hunter At the heart of the party Biography of Raymond Jones, party worker Liberal Democrat History Group Cover picture: ‘Who made the earth?’ from Land Values, February 1914. 2 Journal of Liberal History 46 Spring 2005 Journal of Liberal History Issue 46: Spring 2005 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Land taxing and the Liberals, 1879 – 1914 4 Editor: Duncan Brack Roy Douglas explores why the Liberals of the late nineteenth and early Deputy Editor: Sarah Taft twentieth centuries cared so much about the land question in general, and Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli land value taxation in particular. Biographies Editor: Robert Ingham Reviews Editor: Dr Eugenio Biagini Deputy Reviews Editor: Tom Kiehl Sir Edward Grey’s German love-child 12 The unusual family story of the leading Liberal statesman, recently uncovered Patrons by Hans-Joachim Heller. Dr Eugenio Biagini; Professor Michael Freeden; Professor John Vincent Dundee’s grand old man 16 The life and political career of Edmund Robertson, Lord Lochee of Gowrie Editorial Board (1845–1908); by Anne Newman. Dr Malcolm Baines; Dr Roy Douglas; Dr Barry Doyle; Dr David Dutton; Professor David Gowland; Dr Richard Grayson; Dr Michael Hart; Peter Hellyer; Ian Hunter; Frances Stevenson, Lloyd George and the 24 Dr J. -

The Fall of the Attlee Government, 1951

This is a repository copy of The fall of the Attlee Government, 1951. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85710/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Crowcroft, R and Theakston, K (2013) The fall of the Attlee Government, 1951. In: Heppell, T and Theakston, K, (eds.) How Labour Governments Fall: From Ramsay Macdonald to Gordon Brown. Palgrave Macmillan , Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire , pp. 61-82. ISBN 978-0-230-36180-5 https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137314215_4 © 2013 Robert Crowcroft and Kevin Theakston. This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: dx.doi.org/10.1057/9781137314215_4. Reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit ..................................................................................................................................................