The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Renaissance

1 ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Unit Structure: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 The Historical Overview 1.2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 1.2.1 Political Peace and Stability 1.2.2 Social Development 1.2.3 Religious Tolerance 1.2.4 Sense and Feeling of Patriotism 1.2.5 Discovery, Exploration and Expansion 1.2.6 Influence of Foreign Fashions 1.2.7 Contradictions and Set of Oppositions 1.3 The Literary Tendencies of the Age 1.3.1 Foreign Influences 1.3.2 Influence of Reformation 1.3.3 Ardent Spirit of Adventure 1.3.4 Abundance of Output 1.4 Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.1 Love Poetry 1.4.2 Patriotic Poetry 1.4.3 Philosophical Poetry 1.4.4 Satirical Poetry 1.4.5 Poets of the Age 1.4.6 Songs and Lyrics in Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.7 Elizabethan Sonnets and Sonneteers 1.5 Elizabethan Prose 1.5.1 Prose in Early Renaissance 1.5.2 The Essay 1.5.3 Character Writers 1.5.4 Religious Prose 1.5.5 Prose Romances 2 1.6 Elizabethan Drama 1.6.1 The University Wits 1.6.2 Dramatic Activity of Shakespeare 1.6.3 Other Playwrights 1.7. Let‘s Sum up 1.8 Important Questions 1.0. OBJECTIVES This unit will make the students aware with: The historical and socio-political knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages. Features of the ages. Literary tendencies, literary contributions to the different of genres like poetry, prose and drama. The important writers are introduced with their major works. With this knowledge the students will be able to locate the particular works in the tradition of literature, and again they will study the prescribed texts in the historical background. -

ALL the TIME in the WORLD a Written Creative Work Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State University in Partial Fulfillm

ALL THE TIME IN THE WORLD A written creative work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for 2 6 The Degree 201C -M333 V • X Master of Fine Arts In Creative Writing by Jane Marie McDermott San Francisco, California January 2016 Copyright by Jane Marie McDermott 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read All the Time in the World by Jane Marie McDermott, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Fine Arts: Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Chanan Tigay \ Asst. Professor of Creative Writing ALL THE TIME IN THE WORLD. Jane Marie McDermott San Francisco, California 2016 All the Time in the World is the story of gay young people coming to San Francisco in the 1970s and what happens to them in the course of thirty years. Additionally, the novel tells the stories of the people they meet along-the way - a lesbian mother, a World War II veteran, a drag queen - people who never considered that they even had a story to tell until they began to tell it. In the end, All the Time in the World documents a remarkable era in gay history and serves as a testament to the galvanizing effects of love and loss and the enduring power of friendship. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. Date ACKNOWLEDGMENT Thanks to everyone in the San Francisco State University MFA Creative Writing Program - you rock! I would particularly like to give shout out to Nona Caspers, Chanan Tigay, Toni Morosovich, Barbara Eastman, and Katherine Kwik. -

The Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Literary Journal

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal 2014 The yC borg Griffin: ap S eculative Literary Journal Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cyborg Part of the Fiction Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hollins University, "The yC borg Griffin: a Speculative Literary Journal" (2014). Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal. 3. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cyborg/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Volume IV 2014 The Cyborg Griffin A Speculative Fiction Literary Journal Hollins University ©2014 Tributes Editors Emily Catedral Grace Gorski Katharina Johnson Sarah Landauer Cynthia Romero Editing Staff Rachel Carleton AnneScott Draughon Kacee Eddinger Sheralee Fielder Katie Hall Hadley James Maura Lydon Michelle Mangano Laura Metter Savannah Seiler Jade Soisson-Thayer Taylor Walker Kara Wright Special Thanks to: Jeanne Larsen, Copperwing, Circuit Breaker, and Cyberbyte 2 Table of Malcontents Cover Design © Katie Hall Title Page Image © Taylor Hurley The Machine Princess Hadley James ......................................................................................... -

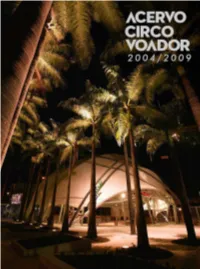

Acervo-Circovoador 2004-2009.Pdf

2004/2009 Primeira Edição Rio de Janeiro 2017 Roberta Sá 19/01/2009 Foto Lucíola Villela EXTRA / Agência O Globo Sumário 6 Circo Voador 8.Apresentação 21.Linha do Tempo/ Coleção de MiniDV 2004/2009 7 Apresentação Depois de mais de sete anos fechado, o Circo 13/07/2004 Voador foi reinaugurado no dia 22 de julho de Foto Michel Filho 2004. Os anos entre o fechamento e a reabertura Agência O Globo foram de muita militância cultural, política e judicial, num movimento que reuniu pessoas da classe artística e políticos comprometidos com as causas culturais. Vencedor de uma ação popular, o Circo Voador ganhou o direito de voltar ao funcionamento, e a prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro ‒ que havia demolido o arcabouço anterior ‒ foi obrigada a construir uma nova estrutura para a casa. Com uma nova arquitetura, futurista e mais atenta às questões acústicas inerentes a uma casa de shows, o Circo retomou as atividades no segundo semestre de 2004 e segue ininterruptamente oferecendo opções de diversão, alegria e formação artística ao público do Rio e a todos os amantes de música e arte em geral. 8 Circo Voador Apresentação Uma característica do Acervo Circo Voador pós-reabertura é que a grande maioria dos eventos tem registro filmado. Ao contrário do período 1982-1996, que conta com uma cobertura significativa mas relativamente pequena (menos de 15% dos shows filmados), após 2004 temos mais de 95% dos eventos registrados em vídeo. O formato do período que este catálogo abrange, que vai de 2004 a 2009, é a fita MiniDV, extremamente popular à época por sua relação custo-benefício e pela resolução de imagem sensivelmente melhor do que outros formatos profissionais e semiprofissionais. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Oswestry, Hay-On-Wye and Berwick-Upon-Tweed: Football Fandom, Nationalism and National Identity Across the Celtic Borders

Oswestry, Hay-on-Wye and Berwick-upon-Tweed: Football fandom, nationalism and national identity across the Celtic borders Robert Bevan School of Welsh Cardiff University 2016 This thesis is submitted to the School of Welsh, Cardiff University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. All rights reserved. 1 Form: PGR_Submission_2014 NOTICE OF SUBMISSION OF THESIS FORM: POSTGRADUATE RESEARCH APPENDIX 1: Specimen layout for Thesis Summary and Declaration/Statements page to be included in a Thesis DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of ………………………… ( PhD) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. -

Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Poetry Review Publications Spring 4-1-1992 Columbia Poetry Review Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Poetry Review" (1992). Columbia Poetry Review. 5. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Poetry Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA POETRY REVIEW Columbia College/Chicago Spring 1992 Columbia Poetry Review is published in the spring of each year by the English Department of Columbia College, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60605. Submissions are encouraged and should be sent to the above address. Subscriptions and sample copies are available at $6.00 an issue. Copyright © I 992 by Columbia College. Grateful acknowledgement is made to Dr. Philip Klukoff, Chairman of the English Department; Dr. Sam Floyd, Academic Vice-President; Lya Rosenblum, D ean of Graduate Studies; Bert Gall, Administrative Vice President; and Mike Alexandroff, President of Columbia College. The cover photograph is by John Mulvany. Student Editors: John -

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II a Thesis Submitted To

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II A thesis submitted to: Lakehead University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts Matthew Sitter Thunder Bay, Ontario July 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother. -

Gloria Swanson

Gloria Swanson: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Title: Gloria Swanson Papers [18--]-1988 (bulk 1920-1983) Dates: [18--]-1988 Extent: 620 boxes, artwork, audio discs, bound volumes, film, galleys, microfilm, posters, and realia (292.5 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this well-known American actress encompass her long film and theater career, her extensive business interests, and her interest in health and nutrition, as well as personal and family matters. Call Number: Film Collection FI-041 Language English. Access Open for research. Please note that an appointment is required to view items in Series VII. Formats, Subseries I. Realia. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase (1982) and gift (1983-1988) Processed by Joan Sibley, with assistance from Kerry Bohannon, David Sparks, Steve Mielke, Jimmy Rittenberry, Eve Grauer, 1990-1993 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Film Collection FI-041 Biographical Sketch Actress Gloria Swanson was born Gloria May Josephine Swanson on March 27, 1899, in Chicago, the only child of Joseph Theodore and Adelaide Klanowsky Swanson. Her father's position as a civilian supply officer with the army took the family to Key West, FL and San Juan, Puerto Rico, but the majority of Swanson's childhood was spent in Chicago. It was in Chicago at Essanay Studios in 1914 that she began her lifelong association with the motion picture industry. She moved to California where she worked for Sennett/Keystone Studios before rising to stardom at Paramount in such Cecil B. -

Red Purge Spreads in Czech

5,000 County Scouts Stage Oceanport Fair SEE PAGE 15 Sunny, Mild Mostly sunny and mild to FINAL day. Clear and cool tonight. Red Bank, Freehold Partly cloudy tomorrow. Long Branch EDITION (Sea Details, Fata 2> 1 JMonmouth County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years /OL. 93, NO. 65 RED BANK, N.J., MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 1969 26 PAGES Register Invites Candidates to Debate Issues KED BANK — The Daily issues, with an opportunity liam T. Cahill and former state Unfair Advertising and Register today invited the for county newsmen to ques- Democratic Gov. Robert B. Packaging Study Commission four candidates in the coas- tion them, the candidates Meyner, for the 10-debate se- because he owns two super- tal district 5B Assembly con* and Sen. Beadleston would ries they had scheduled, markets, opposed legislation test to meet face-to-face in enlighten the voters and "Their example should be mandating transparent pack- the newspaper's conference serve the public interest. followed at all levels of the aging of meat, and because room for a full discussion of Ask Reporters campaign," the Register his legislative aide, James the controversial issues in To assure that the inter- says. Neilland, is executive direc- their battle for election. views reach as many .voters Radio Station WRLB-FM tor of the N. J. Food Coun- The invitation is to Assem- as possible, the Register al- offered the district 5B candi- cil, an organization of super- blymen Joseph Azzolina and so invited newsmen from dates a half-hour last Friday market owners which has lob- James M.