BASP 43-50 Peter Van Minnen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Situation of the Inhabitants of Rhodes and Kos with a Turkish Cultural Background

Doc. 12526 23 February 2011 The situation of the inhabitants of Rhodes and Kos with a Turkish cultural background Report 1 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Rapporteur: Mr Andreas GROSS, Switzerland, Socialist Group Summary The Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights notes that the inhabitants of Rhodes and Kos with a Turkish cultural background are generally well integrated into the multicultural societies of the two islands. It commends the Greek Government for its genuine commitment to maintaining and developing the islands’ cosmopolitan character. The islands’ multiculturalism is the fruit of their rich history, which includes four centuries of generally tolerant Ottoman Turk rule. The good understanding between the majority population and the different minority groups, including that with a Turkish cultural background, is an important asset for the economic prosperity of the islands. The committee notes that better knowledge of the Turkish language and culture would benefit not only the inhabitants with a Turkish cultural background, but also their neighbours. Other issues raised by the inhabitants concerned include the apparent lack of transparency and accountability of the administration of the Muslim religious foundations (vakfs), and the unclear status of the Muslim religious leadership on the islands. The recommendations proposed by the committee are intended to assist the Greek authorities in resolving these issues in a constructive manner. 1 Reference to Committee: Doc. 11904, Reference 3581 of 22 June 2009. F – 67075 Strasbourg Cedex | [email protected] | Tel: + 33 3 88 41 2000 | Fax: +33 3 88 41 2733 Doc. 12526 A. Draft resolution 2 1. The Parliamentary Assembly notes that the inhabitants of Rhodes and Kos with a Turkish cultural background are generally well integrated into the multicultural societies of the two islands. -

Crete in Autumn

Crete in Autumn Naturetrek Tour Report 22 - 29 October 2013 Cyclamen hederifolium Olive Grove Pancratium maritimum Sternbergia sicula Report & images compiled by David Tattersfield Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Crete in Autumn Tour Leader: David Tattersfield Naturetrek Botanist Participants: Jan Shearn Jo Andrews John Andrews Lynne Booth Bernard Booth Frances Druce Christine Holmes Robin Clode Joanne Clode Diane Gee June Oliver John Tarr Vivien Gates Day 1 Tuesday 22nd October The group arrived in Hania on direct flights from Gatwick and Manchester, an hour or so apart. We were met by our driver for the short journey to our hotel and had the remaining part of the afternoon to settle in and explore. We reassembled in the early evening before going out for a delicious selection of traditional Cretan food in a nearby Taverna. Day 2 Wednesday 23rd October We left Hania travelling westwards and after shopping for lunch we made our first stop along the coast at a sandy bay, backed by a small area of dunes. A typical coastal flora included Cottonweed Otanthus maritimus, Sea Holly Eryngium maritimum, the striking spiny grey hummocks of Centaurea spinosa and Sea Daffodil Pancratium maritimum, mostly in fruit, but a few still displaying their spectacular sweetly-scented flowers. South of Kolimbari, on the rocky hillsides above the pretty village of Marathocephala, there were flowers of Cyclamen graecum subsp. graecum, which is restricted to the north-west of the island and the tall flower spikes of Sea Squill, Charybdis maritima. -

Pharaonic Egypt Through the Eyes of a European Traveller and Collector

Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot Esther de Groot s0901245 Book and Digital Media Studies University of Leiden First Reader: P.G. Hoftijzer Second reader: R.J. Demarée 0 1 2 Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot. 3 4 For Harold M. Hays 1965-2013 Who taught me how to read hieroglyphs 5 6 Contents List of illustrations p. 8 Introduction p. 9 Editorial note p. 11 Johann Michael Wansleben: A traveller of his time p. 12 Egypt in the Ottoman Empire p. 21 The journal p. 28 Travelled places p. 53 Acknowledgments p. 67 Bibliography p. 68 Appendix p. 73 7 List of illustrations Figure 1. Giza, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 104 p. 54 Figure 2. The pillar of Marcus Aurelius, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 123 p. 59 Figure 3. Satellite view of Der Abu Hennis and Der el Bersha p. 60 Figure 4. Map of Der Abu Hennis from the original manuscript p. 61 Figure 5. Map of the visited places in Egypt p. 65 Figure 6. Map of the visited places in the Faiyum p. 66 Figure 7. An offering table from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 39 p. 73 Figure 8. A stela from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 40 p. 74 Figure 9. -

MATH 15, CLS 15 — Spring 2020 Problem Set 1, Due 24 January 2020

MATH 15, CLS 15 — Spring 2020 Problem set 1, due 24 January 2020 General instructions for the semester: You may use any references you like for these assignments, though you should not need anything beyond the books on the syllabus and the specified web sites. You may work with your classmates provided you all come to your own conclusions and write up your own solutions separately: discussing a problem is a really good idea, but letting somebody else solve it for you misses the point. When a question just asks for a calculation, that’s all you need to write — make sure to show your work! But if there’s a “why” or “how” question, your answer should be in the form of coherent paragraphs, giving evidence for the statements you make and the conclusions you reach. Papers should be typed (double sided is fine) and handed in at the start of class on the due date. 1. What is mathematics? Early in the video you watched, du Sautoy says the fundamental ideas of mathematics are “space and quantity”; later he says that “proof is what gives mathematics its strength.” English Wikipedia tells us “mathematics includes the study of such topics as quantity, structure, space, and change,” while Simple English Wikipedia says “mathematics is the study of numbers, shapes, and patterns.” In French Wikipedia´ we read “mathematics is a collection of abstract knowledge based on logical reasoning applied to such things as numbers, forms, structures, and transformations”; in German, “mathematics is a science that started with the study of geometric figures and calculations with numbers”; and in Spanish, “mathematics is a formal science with, beginning with axioms and continuing with logical reasoning, studies the properties of and relations between abstract objects like numbers, geometric figures, or symbols” (all translations mine). -

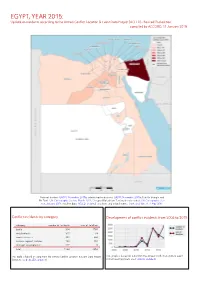

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite? Jodi Magness University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Etruscan Studies Journal of the Etruscan Foundation Volume 8 Article 4 2001 A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite? Jodi Magness University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies Recommended Citation Magness, Jodi (2001) "A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite?," Etruscan Studies: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Etruscan Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Near EasTern EThnic ElemenT Among The ETruscan EliTe? by Jodi Magness INTRODUCTION:THEPROBLEMOFETRUSCANORIGINS 1 “Virtually all archaeologists now agree that the evidence is overwhelmingly in favour of the “indigenous” theory of Etruscan origins: the development of Etruscan culture has to be understood within an evolutionary sequence of social elaboration in Etruria.” 2 “The archaeological evidence now available shows no sign of any invasion, migra- Tion, or colonisaTion in The eighTh cenTury... The formaTion of ETruscan civilisaTion occurred in ITaly by a gradual process, The final sTages of which can be documenTed in The archaeo- logical record from The ninTh To The sevenTh cenTuries BC... For This reason The problem of ETruscan origins is nowadays (righTly) relegaTed To a fooTnoTe in scholarly accounTs.” 3 he origins of the Etruscans have been the subject of debate since classical antiqui- Tty. There have traditionally been three schools of thought (or “models” or “the- ories”) regarding Etruscan origins, based on a combination of textual, archaeo- logical, and linguistic evidence.4 According to the first school of thought, the Etruscans (or Tyrrhenians = Tyrsenoi, Tyrrhenoi) originated in the eastern Mediterranean. -

THE RECENT HİSTORY of the RHODES and KOS TURKS “The Silent Cry Rising in the Aegean Sea”

THE RECENT HİSTORY OF THE RHODES and KOS TURKS “The Silent Cry Rising in the Aegean Sea” Prof. Dr.Mustafa KAYMAKÇI Assoc. Prof. Dr.Cihan ÖZGÜN Translated by: Mengü Noyan Çengel Karşıyaka-Izmir 2015 1 Writers Prof. Dr. Mustafa KAYMAKÇI [email protected] Mustafa Kaymakçı was born in Rhodes. His family was forced to immigrate to Turkey for fear of losing their Turkish identity. He graduated from Ege University Faculty of Agriculture in 1969 and earned his professorship in 1989. He has authored 12 course books and over 200 scientific articles. He has always tried to pass novelties and scientific knowledge on to farmers, who are his target audience. These activities earned him many scientific awards and plaques of appreciation. His achievements include •“Gödence Village Agricultural Development Cooperative Achievement Award, 2003”; •“TMMOB Chamber of Agricultural Engineers Scientific Award, 2004”; and •“Turkish Sheep Breeders Scientific Award, 2009”. His name was given to a Street in Acıpayam (denizli) in 2003. In addition to his course books, Prof. Kaymakçı is also the author of five books on agricultural and scientific policies. They include •Notes on Turkey’s Agriculture, 2009; •Agricultural Articles Against Global Capitalization, 2010; •Agriculture Is Independence, 2011; •Famine and Imperialism, 2012 (Editor); and •Science Political Articles Against Globalization, 2012. Kaymakçı is the President of the Rhodes and Kos and the Dodecanese Islands Turks Culture and Solidarity Association since 1996. Under his presidency, the association reflected the problems of the Turks living in Rhodes and Kos to organizations including Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Parliamentary Association of the European Council (PA CE), the United Nations and the Federal Union of European Nationalities (FEUN). -

Pollen Atlas of the Flora of Egypt 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae

Pollen Atlas of the flora of Egypt * 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae Nahed El-Husseini and Eman Shamso. The Herbarium, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt. El-Husseini, N. & Shamso, E. 2002. The pollen atlas of the flora of Egypt. 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae. Taeckholmia 22(1): 65-76. Light and scanning electron microscope study of the pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae in Egypt was carried out. Pollen grains vary from subspheroidal to prolate; trizonocolpate to trizonocolporate. Exine’s sculpture is striate, colliculate, granulate, coarse reticulate or microreticulate. Seven pollen types are recognized and briefly described, a key distinguishing the different pollen types and the discussion of its systematic value are provided. Key words: Flora of Egypt, pollen atlas, Scrophulariaceae. Introduction The Scrophulariaceae is a family of about 292 genera and nearly 3000 species of cosmopolitan distribution. It is represented in the flora of Egypt by 50 species belonging to 16 genera, 8 tribes and 3 sub-families (El-Hadidi et al., 1999). Within the family, a wide range of pollen morphology exists and provides not only an additional parameter for generic delimitation but also reinforces the validity of many of the larger taxa. Erdtman (1952), gave a concise account of the pollen morphology of some members of the family. Several authors studied and described the pollen of species of the family among whom to mention: Risch (1939), Ikuse (1956), Natarajan (1957), Verghese (1968), Olsson (1974), Elisens (1985c & 1986), Bolliger & Wick (1990) and Argu (1980, 1990 & 1993). Material and Methods Pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae were the subject of the present investigation. -

Taxonomic Revision of the Cretan Fauna of the Genus Temnothorax Mayr, 1861 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with Notes on the Endemism of Ant Fauna of Crete

ANNALES ZOOLOGICI (Warszawa), 2018, 68(4): 769-808 TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE CRETAN FAUNA OF THE GENUS TEMNOTHORAX MAYR, 1861 (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE), WITH NOTES ON THE ENDEMISM OF ANT FAUNA OF CRETE SEBASTIAN SALATA1*, LECH BOROWIEC2, APOSTOLOS TRICHAS3 1Institute for Agricultural and Forest Environment, Polish Academy of Sciences, Bukowska 19, 60-809 Poznań, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Taxonomy, University of Wrocław, Przybyszewskiego 65, 51-148 Wrocław, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] 3Natural History Museum of Crete, University of Crete, Greece; e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract.— We revise the Cretan species of the ant genus Temnothorax Mayr, 1861. Sixteen species are recognized, including seven new species which are possiblyendemic to Crete: T. crassistriatus sp. nov., T. daidalosi sp. nov., T. ikarosi sp. nov., T. incompletus sp. nov., T. minotaurosi sp. nov., T. proteii sp. nov., and T. variabilis sp. nov. A new synonymy is proposed, Temnothorax exilis (Emery, 1869) =Temnothorax specularis (Emery, 1916) syn. nov. An identification key to Cretan Temnothorax, based on worker caste is given. We provide a checklist of ant species described from Crete and discuss their status, distribution and endemism. Ë Key words.— Key, checklist, Myrmicinae, new species, Mediterranean Subregion, new synonymy INTRODUCTION 2000 mm in the high White Mountains range (Lefka Ori) (Grove et al. 1993). Temperature on mountains Crete is the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean seems to fall at a rate of about 6°C per 1000 m (Rack- ham & Moody 1996). Above 1600 m most of the precipi- Sea and the biggest island of Greece. -

A.C. Myshrall

CHAPTER 9. AN INTRODUCTION TO LECTIONARY 299 (A.C. MYSHRALL) Codex Zacynthius, as it is currently bound, is a near-complete Greek gospel lectionary dating to the late twelfth century. Very little work has been done on this lectionary because of the intense interest in the text written underneath. Indeed, New Testament scholars have generally neglected most lectionaries in favour of working on continuous text manuscripts.1 This is largely down to the late date of most of the available lectionaries as well as the assumption that they form a separate, secondary, textual tradition. However, the study of Byzantine lectionaries is vital to understand the development of the use of the New Testament text. Nearly half of the catalogued New Testament manuscripts are lectionaries.2 These manuscripts show us how, in the words of Krueger and Nelson, ‘Christianity is not so much the religion of the New Testament as the religion of its use’.3 These lectionaries were how the Byzantine faithful heard the Bible throughout the Church year, how they interacted with the Scriptures, and they open a window for us to see the worship of a particular community in a particular time and place. THE LECTIONARY A lectionary is a book containing selected scripture readings for use in Christian worship on a given day. The biblical text is thus arranged not in the traditional order of the Bible, but in the order of how the readings appear throughout the year of worship. So, not all of the Bible is included (the Book of Revelation never appears in a Greek lectionary) and the 1 Exceptions to this include the Chicago Lectionary Project (for an overview of the project see Carroll Osburn, ‘The Greek Lectionaries of the New Testament,’ in The Text of the New Testament. -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

A Short History of Greek Mathematics

Cambridge Library Co ll e C t i o n Books of enduring scholarly value Classics From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, Latin and Greek were compulsory subjects in almost all European universities, and most early modern scholars published their research and conducted international correspondence in Latin. Latin had continued in use in Western Europe long after the fall of the Roman empire as the lingua franca of the educated classes and of law, diplomacy, religion and university teaching. The flight of Greek scholars to the West after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 gave impetus to the study of ancient Greek literature and the Greek New Testament. Eventually, just as nineteenth-century reforms of university curricula were beginning to erode this ascendancy, developments in textual criticism and linguistic analysis, and new ways of studying ancient societies, especially archaeology, led to renewed enthusiasm for the Classics. This collection offers works of criticism, interpretation and synthesis by the outstanding scholars of the nineteenth century. A Short History of Greek Mathematics James Gow’s Short History of Greek Mathematics (1884) provided the first full account of the subject available in English, and it today remains a clear and thorough guide to early arithmetic and geometry. Beginning with the origins of the numerical system and proceeding through the theorems of Pythagoras, Euclid, Archimedes and many others, the Short History offers in-depth analysis and useful translations of individual texts as well as a broad historical overview of the development of mathematics. Parts I and II concern Greek arithmetic, including the origin of alphabetic numerals and the nomenclature for operations; Part III constitutes a complete history of Greek geometry, from its earliest precursors in Egypt and Babylon through to the innovations of the Ionic, Sophistic, and Academic schools and their followers.