Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

A Christian's Map of the Holy Land

A CHRISTIAN'S MAP OF THE HOLY LAND Sidon N ia ic n e o Zarefath h P (Sarepta) n R E i I T U A y r t s i Mt. of Lebanon n i Mt. of Antilebanon Mt. M y Hermon ’ Beaufort n s a u b s s LEGEND e J A IJON a H Kal'at S Towns visited by Jesus as I L e o n Nain t e s Nimrud mentioned in the Gospels Caesarea I C Philippi (Banias, Paneas) Old Towns New Towns ABEL BETH DAN I MA’ACHA T Tyre A B a n Ruins Fortress/Castle I N i a s Lake Je KANAH Journeys of Jesus E s Pjlaia E u N s ’ Ancient Road HADDERY TYRE M O i REHOB n S (ROSH HANIKRA) A i KUNEITRA s Bar'am t r H y s u Towns visited by Jesus MISREPOTH in K Kedesh sc MAIM Ph a Sidon P oe Merom am n HAZOR D Tyre ic o U N ACHZIV ia BET HANOTH t Caesarea Philippi d a o Bethsaida Julias GISCALA HAROSH A R Capernaum an A om Tabgha E R G Magdala Shave ACHSAPH E SAFED Zion n Cana E L a Nazareth I RAMAH d r Nain L Chorazin o J Bethsaida Bethabara N Mt. of Beatitudes A Julias Shechem (Jacob’s Well) ACRE GOLAN Bethany (Mt. of Olives) PISE GENES VENISE AMALFI (Akko) G Capernaum A CABUL Bethany (Jordan) Tabgha Ephraim Jotapata (Heptapegon) Gergesa (Kursi) Jericho R 70 A.D. Magdala Jerusalem HAIFA 1187 Emmaus HIPPOS (Susita) Horns of Hittin Bethlehem K TIBERIAS R i Arbel APHEK s Gamala h Sea of o Atlit n TARICHAFA Galilee SEPPHORIS Castle pelerin Y a r m u k E Bet Tsippori Cana Shearim Yezreel Valley Mt. -

When Palestinians Became Human Shields: Counterinsurgency, Racialization, and the Great Revolt (1936–1939)

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(3):625–654. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:10.1017/S0010417521000219 When Palestinians Became Human Shields: Counterinsurgency, Racialization, and the Great Revolt (1936–1939) CHARLES ANDERSON Department of History, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA, USA On 24 September 1936, Palestinian rebel fighters conducted a multipronged assault on British targets in Nablus. The raid was testament to the growing boldness and reach of the rebels, whose power had waxed in late summer as their months-old insurgency deepened throughout the country. During what the military later purported was only a heavy barrage of sniping, the local commanding officer, Brigadier J. F. Evetts, took an extraordinary step as countermeasure. Fearing a decisive rebel offensive on the city’s garrison, he summoned the mayor, Sulayman Tuqan, to army headquarters. Tuqan believed that he was being brought in for consultation with government officials, but when he arrived, he was escorted to the roof of the building, where he was forced to spend the night as a visible, high-value human shield. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

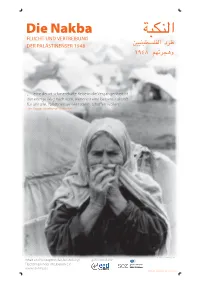

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

United Nations Conciliation.Ccmmg3sionfor Paiestine

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION.CCMMG3SIONFOR PAIESTINE RESTRICTEb Com,Tech&'Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX J$ NON - JlXWISHPOPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARXESHELD BY THE ISRAEL DBFENCEARMY ON X5.49 AS ON 1;4-,45 IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SUMMARY..,,... 1 ACRE SUB DISTRICT . , , . 2 - 3 SAPAD II . c ., * ., e .* 4-6 TIBERIAS II . ..at** 7 NAZARETH II b b ..*.*,... 8 II - 10 BEISAN l . ,....*. I 9 II HATFA (I l l ..* a.* 6 a 11 - 12 II JENIX l ..,..b *.,. J.3 TULKAREM tt . ..C..4.. 14 11 JAFFA I ,..L ,r.r l b 14 II - RAMLE ,., ..* I.... 16 1.8 It JERUSALEM .* . ...* l ,. 19 - 20 HEBRON II . ..r.rr..b 21 I1 22 - 23 GAZA .* l ..,.* l P * If BEERSHEXU ,,,..I..*** 24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH'POPULATION Within the boundaries held 6~~the Israel Defence Army on 1.5.49 . AS ON 1.4.45 Jrr accordance with-. the Palestine Gp~ernment Village ‘. Statistics, April 1945, . SUB DISmICT MOSLEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11,150 6,940 65,380 SAFAD 44,510 1,630 780 46,920 TJBERIAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 Xl, 040 3 38,500 BEISAN lT,92o 650 20 16,590 HAXFA 85,590 30,200 4,330 120,520 JENIN 8,390 60 8,450 TULJSAREM 229310, 10 22,320' JAFFA 93,070 16,300 330 1o9p7oo RAMIIEi 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 I 47,740 HEBRON 19,810 10 19,820 GAZA 69,230 160 * 69,390 BEERSHEBA 53,340 200 10 53,m TOT$L 621,030 92,060 13,710 7z6,8oo . -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons Inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures

Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures Nihad Bokae’e February 2003 Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights PO Box 728 Bethlehem, Palestine [email protected] www.badil.org Socio-historical Overview Internally displaced Palestinians inside Israel are part of the larger Palestinian refugee population that was displaced/expelled from their villages and homes during the 1948 conflict and war in Palestine (i.e., al-Nakba). Most of the refugees were displaced to the Arab states and the Palestinian territories that did not fall under Israeli control (i.e., the West Bank and Gaza Strip). At the end of the war, some 150,000 Palestinians remained in the areas of Palestine that became the state of Israel. This included approximately 30- 40,000 Palestinians who were also displaced during the war. Like the approximately 800,000 Palestinian refugees who were displaced/expelled beyond the borders of the new state, Israel refused to allow internally displaced Palestinians (IDPs) to return to their homes and villages. Displacement did not end with the 1948 war. In the years following the establishment of Israel, internally displaced Palestinians, a small number of refugees who had returned spontaneously to their villages, and Palestinians who had not been displaced during the war were expelled for security and other reasons. Israeli officials also carried out forced transfer of Palestinians from one village to another within the borders of the state in order to facilitate colonization of these areas. This included, for example, Palestinians from the villages of Iqrit, Bir’am, al-Ghabsiyya, Krad al-Baqqarah and Krad al- Ghannamah. -

From the South

VOICES FROM THE SOUTH ewsletter -May 2015 E-N Founded in 1985, the The Karibu Foundation is Karibu Foundation is an an independent founda- independent foundation Acknowledging the Nakba and tion that supports voices that supports voices from from the Global South the Global South that that provide alternatives Struggling for Justice: provide alternatives to to the dominant para- the dominant paradigms Jewish South Africans travel to Lubya digms of power, distribu- of power, distribution, tion, and development. In June 2013, the documentary film “The Village Under the Forest” had its and development. world premiere in Cape Town, South Africa. The film, by Jewish South Africans Mark J. Kaplan and Heidi Grunebaum, presents an example of Visit our website to how a Jewish diaspora has been implicated in the erasure of the memory http://www.karibu.no sign-up for “Voices from of the mass depopulation of Palestinians. [email protected] the South,” our monthly Nearly two years later to the date, in May 2015, a group of Jewish South Afri- e-newsletter. cans (many of whom had been anti-apartheid activists) traveled to Palestine The Karibu Foundation and Israel, in particular to the destroyed Palestinian village of Lubya in the Kirkens Hus http://www.karibu.no Galilee. The aim of their trip was to visit this village under the forest that the Rådhusgt 1-3 documentary described, to stand in solidarity with the village’s Palestinian [email protected] descendants who are still displaced, and to take responsibility for the actions 0151 Oslo being done in their name. Norway This month’s “Voice from the South” features a reflection from Heidi Grune- The Karibu Foundation baum on the South Africans’ visit to Lubya.