Chapter 11. Our Moment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Moment Is Now

173 Our Moment Is Now Ambassador Melanne Verveer and Kim Azzarelli In 1848, Charlotte Woodward was earning a pittance stitching gloves in her home in Waterloo, New York.1 Like other women of her era, the former schoolteacher, not yet twenty years old, had been denied prop- erty ownership rights, citizenship, and political representation. In some states, if a woman married, everything she owned or earned belonged to her husband. That July, Woodward was intrigued by an announcement she read in the newspaper about a meeting of women to be held in a chapel forty miles away, in the town of Seneca Falls. Looking for an opportunity to better her life and that of her family, she did what women have done throughout history and to this day: she joined a network. Woodward’s experience and those of others contextualize the movement for women’s rights and equal participation from a historical perspective, both in the Ambassador Melanne Verveer serves as the Co-Founder of Seneca Women and Executive Director of Georgetown University›s Institute for Women, Peace and Security. She is co-author with Kim Azzarelli of the new book Fast Forward: How Women Can Achieve Power and Purpose and a Founding Partner of Seneca Point Global. In 2009 President Obama appointed Melanne Verveer to be the first ever Ambassador- at-Large for Global Women’s Issues at the U.S. State Department. Ambassador Verveer has a B.A. and M.A. from Georgetown University. She is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and has served as the 2013 Humanitas Visiting Professor at Cambridge University. -

MIT Museum Announces New Exhibition of Holograms and the 9Th International Symposium on Display Holography

Press Advisory Contact Josie Patterson 617-253-4422, [email protected] Press Images - PDF MIT Museum Announces New Exhibition of Holograms and the 9th International Symposium on Display Holography CAMBRIDGE, MA - The MIT Museum announces the opening on June 27, 2012 of The Jeweled Net: Views of Contemporary Holography, an exhibition created in conjunction with the 9th International Symposium on Display Holography, co-sponsored by the MIT Museum and the MIT Media Lab. Over 20 holograms created by international artists, as well as several from the MIT Museum collections, will be on display, and will remain open to the public through September 28, 2013. The exhibition presents a rare opportunity to view selected works from the world-wide community of practicing display holographers. The MIT Museum holds the world’s largest and most comprehensive collection of holograms and regularly invites artists to showcase new work at the Museum. "This new exhibition is an example of our expanded commitment to support public engagement with practicing artists through exhibitions and programs," says Seth Riskin, who will give talks and tours throughout the coming year in his role as the MIT Museum’s Manager of Emerging Technologies and Holography/Spatial Imaging Initiatives. The Jeweled Net: Views of Contemporary Holography surveys state-of-the-art display holography, and showcases the artistic and technical merit of individual works of art. Selected by a panel of experts, the holograms on display represent artists from Germany, Italy, the UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, and the US. Holography has given birth to a new field of science during the past six decades, and as well, to a group of 'pioneers' who have found a new media upon which human vision in three dimensions is transferred. -

Reciu'rernents F°R ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV

THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC A written work submitted to the faculty of ^ ^ San Francisco State University - 7 ' In partial fulfillment of 7o l£ RecIu'rernents f°r ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV Master of Arts In English: Creative Writing By Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Miah Joseph Jeffra 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Violence Almanac by Miah Joseph Jeffra, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written creative work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Arts in English: Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Professor of Creative Writing THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California 2018 The Violence Almanac addresses the relationships between natural phenomena, particularly in geology and biology, and the varied types of violence experienced in American society. Violence is at the core of the collection—how it is caused, how it effects the body and the body politic, and how it might be mitigated. Violence is also defined in myriad ways, from assault to insult to disease to oppression. Many issues of social justice are explored through this lens of violence, and ultimately the book suggests that all oppressive forces function similarly, and that to understand our nature is to understand our culture, and its predilection for oppression. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. ' Chair, Written Creative Work Committee Date ACKNO WLEDG EMENT Thank you to Lambda Literary, Ragdale and the Hub City Writers Project, for allowing me the space to write these stories. -

Extreme Customization

William J. Mitchell, Frank T. Piller, Mitchell Tseng, Ryan Chin, Betty Lou McClanahan (Editors) Extreme Customization Proceedings of the MCPC 2007 World Conference on Mass Customization & Personalization October 7-9, 2007 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology October 11-12, 2007 at the HEC Business School Montreal www.mcpc2007.com Notes 2 Proceedings of the 2007 World Conference on Mass Customization & Personalization Contents Welcome to the MCPC 2007 .......................................................................................................6 MCPC 2007 Conference Overview & Schedule ........................................................................7 About the MCPC Conference Series .......................................................................................12 MCPC 2007 Conference Team..................................................................................................13 MCPC 2007 Hosting Organizations .........................................................................................16 MCPC 2007: Sponsors & Supporters of the MIT Conference ...............................................17 The MIT Smart Customization Group ......................................................................................18 MCPC 2007 Conference Presentations ...................................................................................19 1 Keynote Plenary Presentations.......................................................................................20 2 MCP Showcase & Panel Sessions ..................................................................................24 -

Case 3:15-Cv-30024-MGM Document 1 Filed 02/12/15 Page 1 of 32

Case 3:15-cv-30024-MGM Document 1 Filed 02/12/15 Page 1 of 32 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS WESTERN DIVISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF THE DEAF, on behalf of its members, C. WAYNE DORE, CIVIL ACTION NO. CHRISTY SMITH, LEE NETTLES, and DIANE NETTLES, on behalf of themselves and CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR a proposed class of similarly situated persons DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE defined below, RELIEF Plaintiffs, v. MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, Defendant. Plaintiffs, the National Association of the Deaf, on behalf of its members, and C. Wayne Dore, Christy Smith, Lee Nettles, and Diane Nettles, on behalf of themselves and a proposed class defined below, by and through undersigned counsel, file their Class Action Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief and respectfully allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. Defendant Massachusetts Institute of Technology (“MIT” or “the Institute” or “Defendant”) makes available a variety of online content on websites that have received, to date, at least 125 million visitors.1 MIT makes thousands of videos and audio tracks publicly available for free to anyone with an Internet connection, on broad-ranging topics of educational or general interest. With only a few keystrokes, anyone can access videos ranging from campus talks by President Obama, Noam Chomsky and other “Laureates and Luminaries,” to introductory classes 1 MIT, About OpenCourseWare, http://ocw.mit.edu/about/ (accessed February 3, 2015). Case 3:15-cv-30024-MGM Document 1 Filed 02/12/15 Page 2 of 32 in topics such as computer programming, to higher-level classes in topics such as business and mathematics, to educational videos made by MIT students for use by K-12 students. -

2019Community Involvement Report

MIT LINCOLN LABORATORY COMMUNITY 2019 INVOLVEMENT REPORT Outreach Office MI T LINCOL N LABORATORY A Decade // of Achievement 2018 Lincoln LaboratoryTA Outreach T 6 April 2007– 6 April 20192017 NUMBERS Donated to the American Military Fellows at AScientistsNNUAL & R engineersEPORTS WHoursEBSITE per year supportingLAUNCHED IN CAPABILITIES TECHNICAL Heart Association Lincoln Laboratory volunteering STEM BROCHURES EXCELLENCE AWARDS 300 11 12,15 20080 5,21117 55 10 Care packages Dollars given to the Jimmy Fund Dollars raised for Alzheimer Dollars raised by Laboratory ACTS OOKS EPORTS DAUGHTERS & SONS DAYS DIRECTOR’S OFFICE Fsent to troops B byMIT Laboratory R cyclists Support Community since 2009 employees in 2019 since 2015 MEMOS PROOFREAD 1607 110,792 20+ 549,283 10 1,20620,175$0 Students seeing Students touring Charities receiving Lincoln Laboratory OUTREACH PLAQUES & STUDENTS IN SSTEMTUDENTS demonstrations IN OUR STEM PROGRAMS Lincoln Laboratory donations K-12 STEM programs REWARDS PROGRAMS FAIRS CREATED NOW IN STEM COORDINATED MAJORS 14,00080,000+ 2560+ Money donated to Summer Internships Staff in Lincoln PEN LINCOLN ToysMI Tfor OTots drive STEM PROGRAMS Scholars LABORATORY 37 HOUSE 120 JOURNALS 940 2 274 50 1,0007 200 9 JAC BOOKLETS LLRISE CYBERPATRIOT Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR 02 - 03 04 - 37 01 ∕ EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH 06 K–12 Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Outreach 23 Partnerships with MIT 28 Community Engagement 38 - 59 02 ∕ EDUCATIONAL COLLABORATIONS 40 University Student Programs 45 MIT Student Programs 52 Military Student Programs 58 Technical Staff Programs 60 - 85 03 ∕ COMMUNITY GIVING 62 Helping Those in Need 73 Helping Those Who Help Others 79 Supporting Local Communities A Message From the Director Lincoln Laboratory has built a strong program of educational outreach activities that encourage students to explore science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). -

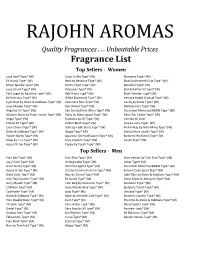

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

The Legacy of Norbert Wiener: a Centennial Symposium

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/pspum/060 Selected Titles in This Series 60 David Jerison, I. M. Singer, and Daniel W. Stroock, Editors, The legacy of Norbert Wiener: A centennial symposium (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, October 1994) 59 William Arveson, Thomas Branson, and Irving Segal, Editors, Quantization, nonlinear partial differential equations, and operator algebra (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, June 1994) 58 Bill Jacob and Alex Rosenberg, Editors, K-theory and algebraic geometry: Connections with quadratic forms and division algebras (University of California, Santa Barbara, July 1992) 57 Michael C. Cranston and Mark A. Pinsky, Editors, Stochastic analysis (Cornell University, Ithaca, July 1993) 56 William J. Haboush and Brian J. Parshall, Editors, Algebraic groups and their generalizations (Pennsylvania State University, University Park, July 1991) 55 Uwe Jannsen, Steven L. Kleiman, and Jean-Pierre Serre, Editors, Motives (University of Washington, Seattle, July/August 1991) 54 Robert Greene and S. T. Yau, Editors, Differential geometry (University of California, Los Angeles, July 1990) 53 James A. Carlson, C. Herbert Clemens, and David R. Morrison, Editors, Complex geometry and Lie theory (Sundance, Utah, May 1989) 52 Eric Bedford, John P. D'Angelo, Robert E. Greene, and Steven G. Krantz, Editors, Several complex variables and complex geometry (University of California, Santa Cruz, July 1989) 51 William B. Arveson and Ronald G. Douglas, Editors, Operator theory/operator algebras and applications (University of New Hampshire, July 1988) 50 James Glimm, John Impagliazzo, and Isadore Singer, Editors, The legacy of John von Neumann (Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York, May/June 1988) 49 Robert C. Gunning and Leon Ehrenpreis, Editors, Theta functions - Bowdoin 1987 (Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine, July 1987) 48 R. -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Cybernetic Apparatus: Media

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Cybernetic Apparatus: Media, Liberalism, and the Reform of the Human Sciences A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Screen Cultures By Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2012 2 © Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan All rights reserved 3 Abstract The Cybernetic Apparatus: Media, Liberalism, and the Reform of the Human Sciences Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan The Cybernetic Apparatus: Media, Liberalism, and the Reform of the Human Sciences examines efforts to reform the human sciences through new forms of technical media. It demonstrates how nineteenth-century political ideals shaped mid-twentieth-century programs for cybernetic research and global science sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation. Through archival research and textual analysis, it reconstructs how and why new media, especially digital technologies, were understood as part of a neutral and impartial apparatus for transcending disciplinary, ethnic, regional, and economic differences. The result is a new account of the role of new media technologies in facilitating international and interdisciplinary collaboration (and critique) in the latter half of the twentieth century. Chapter one examines how political conceptions of communications and technology in the United States in the nineteenth century conditioned the understanding and deployment of media in the twentieth century, arguing that American liberals conceived of technical media as part of a neutral apparatus for overcoming ethnic, geographic, and economic difference in the rapidly expanding nation. Chapter two examines the development of new media instruments as technologies for reforming the natural and human sciences from the 1910s through the 1940s, with particular attention to programs administered by the Rockefeller Foundation. -

MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2Nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected]

2014–2015 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Dani DeSteven About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily contents Photograph by Christopher Brown navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Discover more articles, tips and local business information by visiting the online guide at: www.universityparent.com/mit MIT Guide The presence of university/college logos and marks in this guide does not mean the school | Comprehensive advice and information for student success endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 6 | Welcome to MIT 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 8 | MIT Parents Association Boulder, CO 80301 www.universityparent.com 10 | MIT Parent Giving Top Five Reasons to Join Advertising Inquiries: 11 | (855) 947-4296 12 | 100 Things to Do before Your Student Graduates MIT [email protected] 20 | Academics Top cover photo by Christopher Harting. 21 | Resources for Academic Success 22 | Supporting Your Student 24 | Campus Map 27 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 28 | MIT Police and Campus Safety SARAH SCHUPP PUBLISHER 30 | Housing MARK HAGER DESIGN MIT Dining 32 | MICHAEL FAHLER AD DESIGN 33 | Health Care What to Do On Campus Connect: 36 | 39 | Navigating MIT facebook.com/UniversityParent 41 | Academic Calendar MIT Songs twitter.com/4collegeparents 43 | 45 | Contact Information © 2014 UniversityParent Photo by Tom Gearty 48 | MIT Area Resources 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 5 www.universityparent.com/mit 5 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

Fragrance List 2016

FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 1 Fragrance List 2016 Family Owned & Operated FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 2 LUXURY TUBING ROLLON MEET YOUR OILS NEW BEST FRIENDS B0010 B0011 Starting at only $5.99/Dozen 1 FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 3 LatestLatest FragrancesFragrances PDCT# PRODUCT NAME 1 OZ 2 OZ 4 OZ 8 OZ 1 LB F1530 Always Red For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1557 Amor Amor For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1549 Amor Amor For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1543 Aramis Black For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1515 Ariana Grande Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1561 Bebe Glam Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1511 Black Axe For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1532 Bold For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1535 Born Original For Her Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1536 Born Original For Him Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1559 Br Wildbloom For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1548 Cabotine Fleur De Passion Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1544 Cabotine For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1542 Chrome Intense For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1513 D&G Exotic Leather Type $5.99 $11.98 $14.50 $18.50 $27.50 F1514 D&G Velvet Love Women Type $5.99 $11.98 $14.50 $18.50 $27.50 F1554 Decadence For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1527 Dior Sauvage For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1497 Fire & Ice For Men Type $4.95 $9.00 -

Initiative for a Competitive Brooklyn: Seizing Our Moment

Initiative For A Competitive Brooklyn: Seizing Our Moment Brooklyn Economic Development Corporation Initiative for a Ron Melichar, Director of District Marylin Gelber, Executive Patrick Condren, Management Competitive Brooklyn Management Services and Director, Independence Consultant, Travel/Transportation Committees and Teams Investment, NYC Department of Community Foundation & Economic Development Small Business Services Colvin Grannum, Director, Executive Committee Ellen Oettinger, Economic Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Action Team: Food Processing Development Specialist, Corporation Co-chairs: Co-chairs: Brooklyn Borough Hall Bill Grinker, Chairman, Seedco Adam Friedman, Executive Stanley Brezenoff, President and Dan Wiley, Congresswoman Edison Jackson, President, Director, New York Industrial CEO, Continuum Health Partners Nydia Velazquez’s Office, Medgar Evers College Retention Network Hon. Marty Markowitz, U.S. House of Representatives Stuart Leffler, Manager of Bill Solomon, Owner, Brooklyn Borough President Economic Development for Serengeti Consulting Strategy Board Brooklyn, ConEd Members: Hon. Jim Brennan, New York Jeanne Lutfy, President, Brooklyn Action Team: Health Services Kenneth Adams, President, State Assemblyman Academy of Music LDC Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce Co-chairs: Jonathan Bowles, Research Regina Peruggi, President, Norman Brodsky, President, Director, Center for an Stanley Brezenoff, President and Kingsborough Community CitiStorage Urban Future CEO, Continuum Health Partners College Maurice Coleman, Senior