Variety Selection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting the Most out of Your New Plant Variety

1 INTERNATIONALER INTERNATIONAL UNION VERBAND FOR THE PROTECTION UNION INTERNATIONALE UNIÓN INTERNACIONAL ZUM SCHUTZ VON OF NEW VARIETIES POUR LA PROTECTION PARA LA PROTECCIÓN PFLANZENZÜCHTUNGEN OF PLANTS DES OBTENTIONS DE LAS OBTENCIONES VÉGÉTALES VEGETALES GENF, SCHWEIZ GENEVA, SWITZERLAND GENÈVE, SUISSE GINEBRA, SUIZA Getting the Most Out of Your New Plant Variety By UPOV New varieties of plants (see Box 1) with improved yields, higher quality or better resistance to pests and diseases increase quality and productivity in agriculture, horticulture and forestry, while minimizing the pressure on the environment. The tremendous progress in agricultural productivity in various parts of the world is largely based on improved plant varieties. More so, plant breeding has benefits that extend beyond increasing food production. The development of new improved varieties with, for example, higher quality, increases the value and marketability of crops. In addition, breeding programs for ornamental plants can be of substantial economic importance for an exporting country. The breeding and exploitation of new varieties is a decisive factor in improving rural income and overall economic development. Furthermore, the development of breeding programs for certain endangered species can remove the threat to their survival out in nature, as in the case of medicinal plants. While the process of plant breeding requires substantial investments in terms of money and time, once released, a new plant variety can be easily reproduced in a way that would deprive its breeder of the opportunity to be rewarded for his investment. Clearly, few breeders are willing to spend years making substantial economic investment in developing a new variety of plants if there were no means of protecting and rewarding their commitment. -

EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska- Extension Lincoln Extension 2006 EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Lindgren, Dale T., "EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon" (2006). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 4802. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/4802 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. - CYT vert . File NeBrasKa s Lincoln EXTENSION 85 EC1255 E 'Z oro n~ 1255 ('r'lnV 1 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon (2006) Cooperative Extension Service Extension .circular Received on: 01- 24-07 University of Nebraska, Lincoln - - Libraries Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln 00IANR This is a joint publication of the American Penstemon Society and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. We are grateful to the American Penstemon Society for providing the funding for the printing of this publication. ~)The Board of Regents oft he Univcrsit y of Nebraska. All rights reserved. Table -

William T. Stearn Prize 2010* the Tree As Evolutionary Icon

Archives of natural history 38.1 (2011): 1–17 Edinburgh University Press DOI: 10.3366/anh.2011.0001 # The Society for the History of Natural History www.eupjournals.com/anh William T. Stearn Prize 2010* The tree as evolutionary icon: TREE in the Natural History Museum, London NILS PETTER HELLSTRO¨ M Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, Free School Lane, Cambridge, CB2 3RH, UK (e-mail: [email protected]). ABSTRACT: As part of the Darwin celebrations in 2009, the Natural History Museum in London unveiled TREE, the first contemporary artwork to win a permanent place in the Museum. While the artist claimed that the inspiration for TREE came from Darwin’s famous notebook sketch of branching evolution, sometimes referred to as his “tree of life” drawing, this article emphasises the apparent incongruity between Darwin’s sketch and the artist’s design – best explained by other, complementary sources of inspiration. In the context of the Museum’s active participation in struggles over science and religion, the effect of the new artwork is contradictory. TREE celebrates Darwinian evolutionism, but it resonates with deep-rooted, mythological traditions of tree symbolism to do so. This complicates the status of the Museum space as one of disinterested, secular science, but it also contributes, with or without the intentions of the Museum’s management, to consolidate two sometimes conflicting strains within the Museum’s history. TREE celebrates human effort, secular science and reason – but it also evokes long- standing mythological traditions to inspire reverence and remind us of our humble place in this world. -

The Kennel Club Breed Health Improvement Strategy: a Step-By-Step Guide Improvement Strategy Improvement

BREED HEALTH THE KENNEL CLUB BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY WWW.THEKENNELCLUB.ORG.UK/DOGHEALTH BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE 2 Welcome WELCOME TO YOUR HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY TOOLKIT This collection of toolkits is a resource intended to help Breed Health Coordinators maintain, develop and promote the health of their breed.. The Kennel Club recognise that Breed Health Coordinators are enthusiastic and motivated about canine health, but may not have the specialist knowledge or tools required to carry out some tasks. We hope these toolkits will be a good resource for current Breed Health Coordinators, and help individuals, who are new to the role, make a positive start. By using these toolkits, Breed Health Coordinators can expect to: • Accelerate the pace of improvement and depth of understanding of the health of their breed • Develop a step-by-step approach for creating a health plan • Implement a health survey to collect health information and to monitor progress The initial tool kit is divided into two sections, a Health Strategy Guide and a Breed Health Survey Toolkit. The Health Strategy Guide is a practical approach to developing, assessing, and monitoring a health plan specific to your breed. Every breed can benefit from a Health Improvement Strategy as a way to prevent health issues from developing, tackle a problem if it does arise, and assess the good practices already being undertaken. The Breed Health Survey Toolkit is a step by step guide to developing the right surveys for your breed. By carrying out good health surveys, you will be able to provide the evidence of how healthy your breed is and which areas, if any, require improvement. -

Advances on Research Epigenetic Change of Hybrid and Polyploidy in Plants

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 10(51), pp. 10335-10343, 7 September, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB DOI: 10.5897/AJB10.1893 ISSN 1684–5315 © 2011 Academic Journals Review Advances on research epigenetic change of hybrid and polyploidy in plants Zhiming Zhang†, Jian Gao†, Luo Mao, Qin Cheng, Zeng xing Li Liu, Haijian Lin, Yaou Shen, Maojun Zhao and Guangtang Pan* Maize Research Institute, Sichuan Agricultural University, Xinkang road 46, Ya’an, Sichuan 625014, People’s Republic of China. Accepted 15 April, 2011 Hybridization between different species, and subsequently polyploidy, play an important role in plant genome evolution, as well as it is a widely used approach for crop improvement. Recent studies of the last several years have demonstrated that, hybridization and subsequent genome doubling (polyploidy) often induce an array of variations that could not be explained by the conventional genetic paradigms. A large proportion of these variations are epigenetic in nature. Epigenetic can be defined as a change of the study in the regulation of gene activity and expression that are not driven by gene sequence information. However, the ramifications of epigenetic in plant biology are immense, yet unappreciated. In contrast to the ease with which the DNA sequence can be studied, studying the complex patterns inherent in epigenetic poses many problems. In this view, advances on researching epigenetic change of hybrid and polyploidy in plants will be initially set out by summarizing the latest researches and the basic studies on epigenetic variations generated by hybridization. Moreover, polyploidy may shed light on the mechanisms generating these variations. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Plant Variety Rights Summary Plant Variety Rights Summary

Plant Variety Rights Summary Plant Variety Rights Summary Table of Contents Australia ................................................................................................ 1 China .................................................................................................... 9 Indonesia ............................................................................................ 19 Japan .................................................................................................. 28 Malaysia .............................................................................................. 36 Vietnam ............................................................................................... 46 European Union .................................................................................. 56 Russia ................................................................................................. 65 Switzerland ......................................................................................... 74 Turkey ................................................................................................. 83 Argentina ............................................................................................ 93 Brazil ................................................................................................. 102 Chile .................................................................................................. 112 Colombia .......................................................................................... -

Pho300007 Risk Modeling and Screening for Brcai

?4 101111111111 PHO300007 RISK MODELING AND SCREENING FOR BRCAI MUTATIONS AMONG FILIPINO BREAST CANCER PATIENTS by ALEJANDRO Q. NAT09 JR. A Master's Thesis Submitted to the National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology College of Science University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City As Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY March 2003 In memory of my gelovedmother Mrs. josefina Q -Vato who passedaway while waitingfor the accomplishment of this thesis... Thankyouvery inuchfor aff the tremendous rove andsupport during the beautifil'30yearstfiatyou were udth me... Wom, you are he greatest! I fi)ve you very much! .And.. in memory of 4 collaborating 6reast cancerpatients who passedaway during te course of this study ... I e.Vress my deepest condolence to your (overtones... Tou have my heartfeligratitude! 'This tesis is dedicatedtoa(the 37 cofla6oratingpatients who aftruisticaffyjbinedthisstudyfor te sake offuture generations... iii This is to certify that this master's thesis entitled "Risk Modeling and Screening for BRCAI Mutations among Filipino Breast Cancer Patients" and submitted by Alejandro Q. Nato, Jr. to fulfill part of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology was successfully defended and approved on 28 March 2003. VIRGINIA D. M Ph.D. Thesis Ad RIO SUSA B. TANAEL JR., M.Sc., M.D. Thesis Co-.A. r Thesis Reader The National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology endorses acceptance of this master's thesis as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. -

Technical Working Party for Ornamental Plants and Forest Trees

TWO/30/4 ORIGINAL: English DATE: March 12, 1997 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NEW VARIETIES OF PLANTS GENEVA TECHNICAL WORKING PARTY FOR ORNAMENTAL PLANTS AND FOREST TREES Thirtieth Session Svendborg, Denmark, September 1 to 5, 1997 TESTING THE FIRST VARIETY IN A SPECIES AND THE IDENTIFICATION OF VARIETIES OF COMMON KNOWLEDGE Document prepared by experts from New Zealand n:\orgupov\shared\document\two\two27 to 37\30\30-04.doc TWO/30/4 page 2 TESTING THE FIRST VARIETY IN A SPECIES AND THE IDENTIFICATION OF VARIETIES OF COMMON KNOWLEDGE Chris Barnaby, Examiner of Fruit and Ornamental Varieties, Plant Variety Rights Office, P O Box 24, Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand Introduction New Zealand has experienced a number of problems in the DUS testing of the first variety in a species. In particular, a variety belonging to a species that is not present in New Zealand. When a variety is claimed as a first variety in the species, it is assumed that there are no varieties of common knowledge. This probably will be correct from a national view, however from an international view there may be varieties of common knowledge. The problem then is should the overseas varieties be considered and if yes, how can they be accurately and practically utilized as varieties for comparative DUS testing? In the course of tackling this problem in New Zealand, more general problems associated with the identification of varieties of common knowledge for all varieties under test were identified. From reports at the TWO, other countries are encountering similar problems. This document is intended to generate discussion and perhaps some practical solutions that would be useful to all UPOV member States. -

Crossbreeding Systems for Small Beef Herds

~DMSION OF AGRICULTURE U~l_}J RESEARCH &: EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA3055 Crossbreeding Systems for Small Beef Herds Bryan Kutz For most livestock species, Hybrid Vigor Instructor/Youth crossbreeding is an important aspect of production. Intelligent crossbreed- Generating hybrid vigor is one of Extension Specialist - the most important, if not the most ing generates hybrid vigor and breed Animal Science important, reasons for crossbreeding. complementarity, which are very important to production efficiency. Any worthwhile crossbreeding sys- Cattle breeders can obtain hybrid tem should provide adequate levels vigor and complementarity simply by of hybrid vigor. The highest level of crossing appropriate breeds. However, hybrid vigor is obtained from F1s, sustaining acceptable levels of hybrid the first cross of unrelated popula- vigor and breed complementarity in tions. To sustain F1 vigor in a herd, a a manageable way over the long term producer must avoid backcrossing – requires a well-planned crossbreed- not always an easy or a practical thing ing system. Given this, finding a way to do. Most crossbreeding systems do to evaluate different crossbreeding not achieve 100 percent hybrid vigor, systems is important. The following is but they do maintain acceptable levels a list of seven useful criteria for evalu- of hybrid vigor by limiting backcross- ating different crossbreeding systems: ing in a way that is manageable and economical. Table 1 (inside) lists 1. Merit of component breeds expected levels of hybrid vigor or het- erosis for several crossbreeding sys- 2. Hybrid vigor tems. 3. Breed complementarity 4. Consistency of performance Definitions 5. Replacement considerations hybrid vigor – an increase in 6. -

![The Arithmetic of Genus Two Curves Arxiv:1209.0439V3 [Math.AG] 6 Sep](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2518/the-arithmetic-of-genus-two-curves-arxiv-1209-0439v3-math-ag-6-sep-702518.webp)

The Arithmetic of Genus Two Curves Arxiv:1209.0439V3 [Math.AG] 6 Sep

The arithmetic of genus two curves 1 T. SHASKA 2 Department of Mathematics, Oakland University L. BESHAJ 3 Department of Mathematics, University of Vlora. Abstract. Genus 2 curves have been an object of much mathematical interest since eighteenth century and continued interest to date. They have become an important tool in many algorithms in cryptographic applications, such as factoring large numbers, hyperelliptic curve cryp- tography, etc. Choosing genus 2 curves suitable for such applications is an important step of such algorithms. In existing algorithms often such curves are chosen using equations of moduli spaces of curves with decomposable Jacobians or Humbert surfaces. In these lectures we will cover basic properties of genus 2 curves, mod- uli spaces of (n,n)-decomposable Jacobians and Humbert surfaces, mod- ular polynomials of genus 2, Kummer surfaces, theta-functions and the arithmetic on the Jacobians of genus 2, and their applications to cryp- tography. The lectures are intended for graduate students in algebra, cryptography, and related areas. Keywords. genus two curves, moduli spaces, hyperelliptic curve cryptography, modular polynomials 1. Introduction Genus 2 curves are an important tool in many algorithms in cryptographic ap- plications, such as factoring large numbers, hyperelliptic curve cryptography, etc. arXiv:1209.0439v3 [math.AG] 6 Sep 2012 Choosing such genus 2 curves is an important step of such algorithms. Most of genus 2 cryptographic applications are based on the Kummer surface Ka;b;c;d. Choosing small a; b; c; d makes the arithmetic on the Jacobian very fast. However, only a small fraction of all choices of a; b; c; d are secure. -

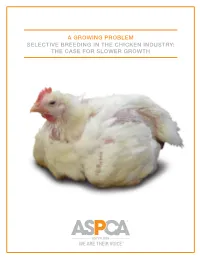

A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry

A GROWING PROBLEM SELECTIVE BREEDING IN THE CHICKEN INDUSTRY: THE CASE FOR SLOWER GROWTH A GROWING PROBLEM SELECTIVE BREEDING IN THE CHICKEN INDUSTRY: THE CASE FOR SLOWER GROWTH TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................. 2 SELECTIVE BREEDING FOR FAST AND EXCESSIVE GROWTH ......................... 3 Welfare Costs ................................................................................. 5 Labored Movement ................................................................... 6 Chronic Hunger for Breeding Birds ................................................. 8 Compromised Physiological Function .............................................. 9 INTERACTION BETWEEN GROWTH AND LIVING CONDITIONS ...................... 10 Human Health Concerns ................................................................. 11 Antibiotic Resistance................................................................. 11 Diseases ............................................................................... 13 MOVING TO SLOWER GROWTH ............................................................... 14 REFERENCES ....................................................................................... 16 COVER PHOTO: CHRISTINE MORRISSEY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In an age when the horrors of factory farming are becoming more well-known and people are increasingly interested in where their food comes from, few might be surprised that factory farmed chickens raised for their meat—sometimes called “broiler”