A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kennel Club Breed Health Improvement Strategy: a Step-By-Step Guide Improvement Strategy Improvement

BREED HEALTH THE KENNEL CLUB BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY WWW.THEKENNELCLUB.ORG.UK/DOGHEALTH BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE 2 Welcome WELCOME TO YOUR HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY TOOLKIT This collection of toolkits is a resource intended to help Breed Health Coordinators maintain, develop and promote the health of their breed.. The Kennel Club recognise that Breed Health Coordinators are enthusiastic and motivated about canine health, but may not have the specialist knowledge or tools required to carry out some tasks. We hope these toolkits will be a good resource for current Breed Health Coordinators, and help individuals, who are new to the role, make a positive start. By using these toolkits, Breed Health Coordinators can expect to: • Accelerate the pace of improvement and depth of understanding of the health of their breed • Develop a step-by-step approach for creating a health plan • Implement a health survey to collect health information and to monitor progress The initial tool kit is divided into two sections, a Health Strategy Guide and a Breed Health Survey Toolkit. The Health Strategy Guide is a practical approach to developing, assessing, and monitoring a health plan specific to your breed. Every breed can benefit from a Health Improvement Strategy as a way to prevent health issues from developing, tackle a problem if it does arise, and assess the good practices already being undertaken. The Breed Health Survey Toolkit is a step by step guide to developing the right surveys for your breed. By carrying out good health surveys, you will be able to provide the evidence of how healthy your breed is and which areas, if any, require improvement. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Characteristics of a Good Breeder

WHAT CHARACTERIZES A GOOD BREEDER? By Carissa Kuehn Looking for a German Shepherd puppy? It can be a daunting task; there are endless numbers of “breeders” out there with all sorts of claims to fame: “specializing in blacks and black sables”, “top-rated show line dogs”, “top- rated working dogs”, “specializing in huge „Old World‟ German Shepherds”. How does one make sense of it all? fter spending a total of six years A searching for and investigating my GSD breeder—and finally getting a puppy from her that I have since taken all the way from BH to IPO3 at the Regional and National championship levels as a first time handler—I have learned many things about good breeders that I wish to share. There are several key characteristics and attributes that set a GOOD BREEDER apart from all those other “breeders” out there. My hope is that this article helps guide you in selecting a good breeder who works tirelessly to produce good German Shepherd Dogs that are all a German Shepherd should be. I hope that it also helps you avoid those breeders who are either just in it for the money, or have no real knowledge about and experience in breeding good German Shepherd Dogs. The author with “Axel”, competing at the 2013 USCA GSD IPO3 National Whether you want a stable, well-bred Championship (first National event as a first-time handler with her first GSD German Shepherd Dog for a companion, ever. A combination of a good breeder, a good dog, and a good training team!). -

Pho300007 Risk Modeling and Screening for Brcai

?4 101111111111 PHO300007 RISK MODELING AND SCREENING FOR BRCAI MUTATIONS AMONG FILIPINO BREAST CANCER PATIENTS by ALEJANDRO Q. NAT09 JR. A Master's Thesis Submitted to the National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology College of Science University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City As Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY March 2003 In memory of my gelovedmother Mrs. josefina Q -Vato who passedaway while waitingfor the accomplishment of this thesis... Thankyouvery inuchfor aff the tremendous rove andsupport during the beautifil'30yearstfiatyou were udth me... Wom, you are he greatest! I fi)ve you very much! .And.. in memory of 4 collaborating 6reast cancerpatients who passedaway during te course of this study ... I e.Vress my deepest condolence to your (overtones... Tou have my heartfeligratitude! 'This tesis is dedicatedtoa(the 37 cofla6oratingpatients who aftruisticaffyjbinedthisstudyfor te sake offuture generations... iii This is to certify that this master's thesis entitled "Risk Modeling and Screening for BRCAI Mutations among Filipino Breast Cancer Patients" and submitted by Alejandro Q. Nato, Jr. to fulfill part of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology was successfully defended and approved on 28 March 2003. VIRGINIA D. M Ph.D. Thesis Ad RIO SUSA B. TANAEL JR., M.Sc., M.D. Thesis Co-.A. r Thesis Reader The National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology endorses acceptance of this master's thesis as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. -

Insights Into Breed Standards Written by Dr Al Grossman and Reprinted with Permission

Breeders’ Briefcase by Amy & Bonnie Insights Into Breed Standards Written by Dr Al Grossman and reprinted with permission We have all heard a variety of finish its championship. references to soundness. It may be, “I It is practically impossible to divorce don’t care for so and so’s dog but he type from soundness completely, is sound”, or “isn’t so and so lovely, for it might be said that soundness and so sound too.” Various words have is the cause and type the effect. I been used to define “sound.” Some have always used the analogy from of them are (1) free from flaw, defect home building that soundness is or decay, undamaged or unimpaired, the basement and framework of (2) healthy, not weak or diseased, the building. Type is the goodies robust of body and mind. Continuing, added on to make it a livable house. there are flawless, perfect, sturdy, Expression, coat, etc. define your dependable, reliable, etc. Are you final impression of the dog. beginning to get the picture? It should be pointed out that a sound Most breeds have been bred for a dog is not necessarily championship purpose, and as such, is required to material, since the word “show” have the stamina and traits necessary itself connotes that a little more is to perform its function, coupled required. with the necessary instincts. Thus, soundness should mean that the Generally speaking, when a breeder animal is able to carry out the job for describes a sound specimen, he which it is intended. It should mean means a dog without a major fault. -

Crossbreeding Systems for Small Beef Herds

~DMSION OF AGRICULTURE U~l_}J RESEARCH &: EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA3055 Crossbreeding Systems for Small Beef Herds Bryan Kutz For most livestock species, Hybrid Vigor Instructor/Youth crossbreeding is an important aspect of production. Intelligent crossbreed- Generating hybrid vigor is one of Extension Specialist - the most important, if not the most ing generates hybrid vigor and breed Animal Science important, reasons for crossbreeding. complementarity, which are very important to production efficiency. Any worthwhile crossbreeding sys- Cattle breeders can obtain hybrid tem should provide adequate levels vigor and complementarity simply by of hybrid vigor. The highest level of crossing appropriate breeds. However, hybrid vigor is obtained from F1s, sustaining acceptable levels of hybrid the first cross of unrelated popula- vigor and breed complementarity in tions. To sustain F1 vigor in a herd, a a manageable way over the long term producer must avoid backcrossing – requires a well-planned crossbreed- not always an easy or a practical thing ing system. Given this, finding a way to do. Most crossbreeding systems do to evaluate different crossbreeding not achieve 100 percent hybrid vigor, systems is important. The following is but they do maintain acceptable levels a list of seven useful criteria for evalu- of hybrid vigor by limiting backcross- ating different crossbreeding systems: ing in a way that is manageable and economical. Table 1 (inside) lists 1. Merit of component breeds expected levels of hybrid vigor or het- erosis for several crossbreeding sys- 2. Hybrid vigor tems. 3. Breed complementarity 4. Consistency of performance Definitions 5. Replacement considerations hybrid vigor – an increase in 6. -

PLANT BREEDING David Luckett and Gerald Halloran ______

CHAPTER 4 _____________________________________________________________________ PLANT BREEDING David Luckett and Gerald Halloran _____________________________________________________________________ WHAT IS PLANT BREEDING AND WHY DO IT? Plant breeding, or crop genetic improvement, is the production of new, improved crop varieties for use by farmers. The new variety may have higher yield, improved grain quality, increased disease resistance, or be less prone to lodging. Ideally, it will have a new combination of attributes which are significantly better than the varieties already available. The new variety will be a new combination of genes which the plant breeder has put together from those available in the gene pool of that species. It may contain only genes already existing in other varieties of the same crop, or it may contain genes from other distant plant relatives, or genes from unrelated organisms inserted by biotechnological means. The breeder will have employed a range of techniques to produce the new variety. The new gene combination will have been chosen after the breeder first created, and then eliminated, thousands of others of poorer performance. This chapter is concerned with describing some of the more important genetic principles that define how plant breeding occurs and the techniques breeders use. Plant breeding is time-consuming and costly. It typically takes more than ten years for a variety to proceed from the initial breeding stages through to commercial release. An established breeding program with clear aims and reasonable resources will produce a new variety regularly, every couple of years or so. Each variety will be an incremental improvement upon older varieties or may, in rarer circumstances, be a quantum improvement due to some novel gene, the use of some new technique or a response to a new pest or disease. -

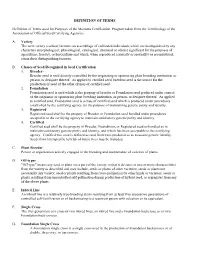

Definition of Terms

DEFINITION OF TERMS Definition of Terms used for Purposes of the Montana Certification Program taken from the Terminology of the Association of Official Seed Certifying Agencies. A. Variety The term variety (cultivar) denotes an assemblage of cultivated individuals which are distinguished by any characters (morphological, physiological, cytological, chemical or others) significant for the purposes of agriculture, forestry, or horticulture and which, when reproduced (sexually or asexually) or reconstituted, retain their distinguishing features. B. Classes of Seed Recognized in Seed Certification 1. Breeder - Breeder seed is seed directly controlled by the originating or sponsoring plant breeding institution, or person, or designee thereof. As applied to certified seed, breeders seed is the source for the production of seed of the other classes of certified seed. 2. Foundation Foundation seed is seed which is the progeny of breeder or Foundation seed produced under control of the originator or sponsoring plant breeding institution, or person, or designee thereof. As applied to certified seed, Foundation seed is a class of certified seed which is produced under procedures established by the certifying agency for the purpose of maintaining genetic purity and identity. 3. Registered Registered seed shall be the progeny of Breeder or Foundation seed handled under procedures acceptable to the certifying agency to maintain satisfactory genetic purity and identity. 4. Certified Certified seed shall be the progeny of Breeder, Foundation, or Registered seed so handled as to maintain satisfactory genetic purity and identity, and which has been acceptable to the certifying agency. Certified tree seed is defined as seed from trees produced so as to assure genetic identity. -

Review of the Current State of Genetic Testing - a Living Resource

Review of the Current State of Genetic Testing - A Living Resource Prepared by Liza Gershony, DVM, PhD and Anita Oberbauer, PhD of the University of California, Davis Editorial input by Leigh Anne Clark, PhD of Clemson University July, 2020 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 I. The Basics ......................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Modes of Inheritance ....................................................................................................................... 7 a. Mendelian Inheritance and Punnett Squares ................................................................................. 7 b. Non-Mendelian Inheritance ........................................................................................................... 10 III. Genetic Selection and Populations ................................................................................................ 13 IV. Dog Breeds as Populations ............................................................................................................. 15 V. Canine Genetic Tests ...................................................................................................................... 16 a. Direct and Indirect Tests ................................................................................................................ 17 b. Single -

Expectation of Means and Variances of Backcross Individuals and Their

Heredity 59 (1987) 105—115 The Genetical Society of Great Britain Received 2 October 1986 Expectation of means and variances of testcrosses produced from F2 and backcross individuals and their selfed progenies A. E. Meichinger Institute of Plant Breeding, Seed Science and Population Genetics, University of Hohenheim, P.O. Box 70 05 62, D-7000 Stuttgart 70, F.R.G. A biometrical genetic model is presented for the testcross performance of genotypes derived from a cross between two pure-breeding lines. The model is applied to obtain the genetical expectations of first andseconddegree statistics of testcrosses established from F2, first and higher backcross populations and their selfing generations. Theoretically, the testcross mean of these populations is expected to be a linear function of the percentage of germplasm from each parent line in the absence of epistasis. In both F2 and backcross populations, the new arising testcross variance between sublines is halved with each additional generation of selfing. Special consideration is given to the effects of linkage and epistasis, and tests for their presence are provided. The results are discussed with respect to implications in "second cycle" breeding. It is concluded that the choice of base populations between F2 and first backcrosses can be made on the distributions of testerosses from the first segregating generation. Schnell's (1983) "usefulness" criterion is recommended for choosing the optimum type of base population. INTRODUCTION solution to the problem of choosing the most promising lines for improving the parents of a Inan advanced stage of hybrid breeding e.g., in single cross. Theoretical results for comparing F2 maize (Zea mays L.), new lines are predominantly and backcross populations with regard to per se developed either from advanced populations performance were provided by Mather, Jinks and undergoing recurrent selection or from ad hoc co-workers (see Mather and Jinks, 1982). -

Management of Replacement Heifers for a High Reproductive and Calving Rate

B - 1213 Management of Replacement Heifers for a High Reproductive and Calving Rate L. R. Sprott and T. R. Troxel * A profitable beef operation involves producing the low group and 19 pounds more than the medium maximum pounds of beef at the least possible cost. group. Notice that 70 percent of these heavier, Profitability is primarily dependent on reproductive faster gaining calves were born in the first 20 days performance, which is best measured by percent of the calving season. calf crop. "Percent calf crop", is the number of calves weaned, divided by the number of cows in In addition to weaning heavier calves, cows calving the breeding herd at the start of the breeding early in the calving season have better rebreeding season. rates than cows calving late in the calving season (4, 5, 6). The herd should be managed to increase This statistic varies widely in Texas, with some the proportion of early calving cows. Such things as herds having 30 to 50 percent calf crops and others disease control, adequate nutrition, annual culling of 90 percent or greater. Obviously, the closer the calf open and late calving cows, and proper heifer crop is to 100 percent, the more calves there are to management are essential elements of market and the better the recovery of direct costs management for earliness of calving. Good heifer associated with the cow herd. management maybe the most critical management tool. It produces a uniform group of heifers that, In many beef operations calves are weaned at a when given an opportunity to conceive early in the given time; therefore, cows calving late in the first breeding season, will calve early in the first calving season wean smaller calves than do cows calving season. -

Puppy Guarantee

Bullies 4 The Brave, Inc. PUPPY GUARANTEE I ________________________________________________ have read the below information (First Name/Last Name) regarding the puppy guarantee and agree to all within,____________________. (Date) Please copy, print and sign that you have read and understand the below Health Guarantee. It must be mailed or emailed to us before your puppy leaves. REGULAR MONTHLY VET CHECKS WILL ALLOW THIS GUARANTEE TO BE DOCUMENTED BY YOUR VET- YOU MUST HAVE A PAPER TRAIL FOR YOUR PUPPY'S HEALTH GUARANTEE INCLUDING VET WORMING & SHOT RECORDS. WEIGHT AND HEIGHT OF YOUR PUPPY MUST BE DOCUMENTED AS WELL AS VETS COMMENTS FOR HIS/HER OVERALL HEALTH. YOU MUST KEEP AND FURNISH REGULAR MONTHLY VET VISIT RECORDS AND FOOD RECEIPTS FOR THE FIRST YEAR OF LIFE. IF YOU HAVE NOT DONE THIS THE HEALTH GUARANTEE IS NULL AND VOID, WE WILL NOT COVER YOUR PET BECAUSE IT IS THAT IMPORTANT FOR A HEALTHY PUPPY THAT THESE THINGS BE DONE. WE ALSO HAVE THE RIGHT TO CALL YOUR VET AND VERIFY INFORMATION ABOUT YOUR PUPPY IF THERE IS A PROBLEM THAT ARISES. Health Guarantee The Olde English Bulldogge is quickly becoming well respected in many working venues such as weight pull, therapy training, obedience and several others. They have become excellent breathers and do not have to be kept in an air conditioned environments on most days; as with any breed heat stroke can happen if proper care is not taken with your pet. The Olde English Bulldogge may be a healthier breed of dog than many modern Bulldog breeds; HOWEVER, the Bulldogge has been recreated using its counterpart the English bulldog and certain genes can pull from generations long ago so it is important to read and understand about these types of bulldog defects.