Mercia Rocks OUGS West Midlands Branch Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Geological

NEWSLETTER No. 44 - April, 1984 : Editorial : Over the years, pen poised over blank paper, I have sometimes had a wicked urge to write an ed- itorial on the problems of writing an editorial. For this issue I was asked to consider something on the low attendances at a few recent meetings and this would have been a sad topic. In the lic1^ meantime we have had two meetings with large at- tvndances, further renewed subscriptions, and various other problems solved. This leaves your Country editor much happier, and quite willing to ask you to keep it up = Geological This issue has been devoted mainly to the two long articles on the local limestone and its n !''} Q problems, so for this time the feature "From the Papers" is omitted. Next Meeting : Sunday April 15th : Field trip led by Tristram Besterman to Warwick and Nuneaton. Meet 10.00 a.m. at the Museum, Market Place, Warwick, The Museum will be open, allowing us to see the geological displays, some of the reserve collections, and the Geological Locality Record Centre. This will be followed by a visit to a quarry exposing the Bromsgrove Sandstone (Middle Triassic). In the afternoon it is proposed to visit the Nuneaton dis- trict to examine the Precambrian-Cambrian geology, and to see examples of site conservation. Meetings are held in the Allied Centre, Green Ilan Entry, Tower Street, Dudley, behind the Malt Shovel pub. Indoor meetings commence at 8 p.m. with coffee and biscuits (no charge) from 7.15 p.m. Field meetings will commence from outside the Allied Centre unlegs otherwise arranged. -

The Past, Present, and Future of English Dialects: Quantifying Convergence, Divergence, and Dynamic Equilibrium

Language Variation and Change, 22 (2010), 69–104. © Cambridge University Press, 2010 0954-3945/10 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394510000013 The past, present, and future of English dialects: Quantifying convergence, divergence, and dynamic equilibrium WARREN M AGUIRE AND A PRIL M C M AHON University of Edinburgh P AUL H EGGARTY University of Cambridge D AN D EDIU Max-Planck-Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT This article reports on research which seeks to compare and measure the similarities between phonetic transcriptions in the analysis of relationships between varieties of English. It addresses the question of whether these varieties have been converging, diverging, or maintaining equilibrium as a result of endogenous and exogenous phonetic and phonological changes. We argue that it is only possible to identify such patterns of change by the simultaneous comparison of a wide range of varieties of a language across a data set that has not been specifically selected to highlight those changes that are believed to be important. Our analysis suggests that although there has been an obvious reduction in regional variation with the loss of traditional dialects of English and Scots, there has not been any significant convergence (or divergence) of regional accents of English in recent decades, despite the rapid spread of a number of features such as TH-fronting. THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ENGLISH DIALECTS Trudgill (1990) made a distinction between Traditional and Mainstream dialects of English. Of the Traditional dialects, he stated (p. 5) that: They are most easily found, as far as England is concerned, in the more remote and peripheral rural areas of the country, although some urban areas of northern and western England still have many Traditional Dialect speakers. -

Teaching the Art of Poetry Using Dialect in Your Poems

TEACHING THE ART OF POETRY USING DIALECT IN YOUR POEMS by Liz Berry hinny … glinder … jinnyspins … dayclean1 Choosing to write poems using dialect is like finding a locked box full of treasure. You know there’s all sorts of magical things inside, you just have to find the key that will let you in. So put down your notebook, close your laptop, and start listening to the voices around you. For this is the way in, the place where the strongest dialect poetry starts: a voice you can hear. That’s how writing in Black Country dialect started for me - by listening to the voices of the area I’d grown up in. The Black Country dialect has long been mocked as guttural and middle-earthy but to me it’s beautiful because the people I love best have spoken it. None of them are poets but to me their language is the stuff of poetry. I started listening more carefully, rooting around in the past. It was like digging up my own Staffordshire Hoard; a field full of spectacular words, sounds and phrases glinting out of the muck. I was inspired by other poets who’d written using dialect. The brilliant Faber Book of Vernacular Verse edited by Tom Paulin presents a wonderful alternative poetic tradition. It praises the 'springy, irreverent, chanting, often tender and intimate, vernacular voice … which speaks for an alternative community that is mostly powerless and invisible'. Contemporary poets like Kathleen Jamie, Daljit Nagra and Jen Hadfield continue the tradition in fresh and irresistible ways. Reading their work you’re bowled over by the fizz and charm of dialect and how poetry can be a powerful way of protecting and celebrating the spoken language of regions and communities. -

Geofest 2014 Download FINAL

Where booking details are given, bookings are essential GeoFest June 2014 26th May to 31st August Monday 26th May: Family Event Saturday 7th June: Family Event ‘Rock On!’. Come and learn about rocks, building stones ‘Building Stones Roadshow’. Lots of fun and family friendly and minerals as part of the Brilliant Building Stones project geology and building stones activities to make and do. What’s On! with experts from the Earth Heritage Trust. Enjoy making Displays and experts at the event throughout the day. your own dinosaurs and meet Vernon the Velociraptor. Start: 11am at Bewdley Museum, Load Street, DY12 2AE Start: 11am at Worcestershire County Museum, Hartlebury Finish: 3pm Cost: Free to attend Castle, Hartlebury, DY11 7XZ Finish: 5pm Cost: Museum admission fee Thursday 12th June: Illustrated Talk ‘Minerals of the Malvern Hills’. A feast of photos and a 17th May - 22nd June sprinkling of history which reveal the hidden ingredients of Exhibition the Malvern Hills. From the Mountains to the Sea Start: 7.30pm at Malvern Hills GeoCentre, Walwyn Road, Upper Colwall nr Malvern, WR13 6PL Finish: 8.30pm An exhibition of work by Textile artist Georgia Jacobs Cost: £3 Booking: 01905 855184 / [email protected] based upon geological locations in the British Isles. Monday 16th June: Painting Workshop Saturday 31st May & Sunday 1st June With local artist Diane Jennings, create your own beautiful Textile technique demonstrations by Georgia Jacobs oil or acrylic painting. You don't need any previous experience in painting or drawing. Diane provides all the Bewdley Museum, Load Street, Bewdley, DY12 2AE equipment, paint, canvas and instructions. -

The Life & Times of Mortimer Forest

The Life & Times of Mortimer Forest Mortimer Forest Marked trails All Ability Trail - 1.6 km (1 mile) Vinnalls Loop Trail - 4.8 km (3 miles) Whitcliffe Climbing Jack Trail - 4.5 km (9 miles) Car Park Black Pool Loop Trail - 2.4 km (1.5 miles) Whitcliffe Loop Trail - 3.3 km (2 miles) Vinnalls Car Park Black Pool Car Park 1 km Foreword Woodlands are important places for butterflies and moths with 16 of Britain’s butterflies considered woodland specialists and 380 of the larger moths. Butter- flies and moths form an important part of the food chain for bats and birds, have a key role to play as pollinators and are good biodiversity indicators as they respond rapidly to changing environments. The Mortimer Forest is a significant area of woodland because of its size, the range of butterflies and moths that have been recorded, and its location in a larger wooded landscape. I first visited when I carried out survey work for fritil- lary butterflies, which are in serious decline nationally, in the early 1990s and it is somewhere I have grown to appreciate more and more on subsequent visits. While there have been occasional butterfly and moth records from Mortimer Forest since then, the Forest has never had the equivalent levels of recording of other forests of similar size, largely as a result of its rural position and the lack of a local recording group. For the past three years, Butterfly Conservation has been working in close partnership with the Forestry Commission with the aim of engaging with communities and encouraging them to become involved with the surveying of butterflies and moths and with practical conservation work. -

LINGUISTIC CONTEXT of H-DROPPING Heinrich RAMISCH University of Bamberg Heinrich

Dialectologia. Special issue, I (2010), 175-184. ISSN: 2013-22477 ANALYSING LINGUISTIC ATLAS DATA: THE (SOCIO-) LINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF H-DROPPING Heinrich R AMISCH University of Bamberg [email protected] Abstract This presentation will seek to illustrate how linguistic atlas data can be employed to obtain a better understanding of the mechanisms of linguistic variation and change. For this purpose, I will take a closer look at ‘H-dropping’ – a feature commonly found in various European languages and also widely used in varieties of British English. H-dropping refers to the non-realization of /h/ in initial position in stressed syllables before vowels, as for example, in hand on heart [ 'ænd ɒn 'ɑː t] or my head [m ɪ 'ɛd]. It is one of the best-known nonstandard features in British English, extremely widespread, but also heavily stigmatised and commonly regarded as ‘uneducated’, ‘sloppy’, ‘lazy’, etc. It prominently appears in descriptions of urban accents in Britain (cf. Foulkes/Docherty 1999) and according to Wells (1982: 254), it is “the single most powerful pronunciation shibboleth in England”. H-dropping has frequently been analysed in sociolinguistic studies of British English and it can indeed be regarded as a typical feature of working-class speech. Moreover, H-dropping is often cited as one of the features that differentiate ‘Estuary English’ from Cockney, with speakers of the former variety avoiding ‘to drop their aitches’. The term ‘Estuary English’ is used as a label for an intermediate variety between the most localised form of London speech (Cockney) and a standard form of pronunciation in the Greater London area. -

The Black Country Annual Economic Review 2019

THE BLACK COUNTRY Annual Economic Review THE BLACK COUNTRY - A PLACE TO WORK, LIVE, INVEST 01 Introduction “The Black Country Economic Review is produced annually by the Black Country Consortium’s Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU) to provide an overview of the Black Country’s economic performance during the year. The report measures success as set out in our Performance Management Framework and enables us to monitor real progress towards delivery of the Black Country Strategic Economic Plan (SEP). Significant developments in 2018 include the development of a West Midlands Local Industrial Strategy (LIS), a unique opportunity to drive increased productivity and inclusive growth across the region. The Black Country Economic Intelligence Unit has played a fundamental role in the development of the West Midlands LIS, in particular utilising experienced skill sets to provide the deep, diverse and robust evidence base that underpins the strategy. The EIU is Stewart Towe CBE DL also a key delivery partner in the recently launched Midlands Engine Observatory.” Chairman of the Black Country Consortium How We Measure Success The Black Country Performance Management Framework The Black Country Performance Management Framework (PMF) set out on page 3, provides a clear framework to monitor progress and the changes required to achieve our 30-year Vision and the ambitions across the twelve programmes in our Strategic Economic Plan (SEP). This framework was politically endorsed by the Association of Black Country Local Authorities in 2004 and is updated and reported annually. The PMF is maintained and updated by the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU) of Black Country Consortium Ltd who provide in depth cross-thematic spatial analysis on the Black Country economy on behalf of the Black Country Consortium and the Local Enterprise Partnership. -

Murchison in the Welsh Marches: a History of Geology Group Field Excursion Led by John Fuller, May 8 – 10 , 1998

ISSN 1750-855X (Print) ISSN 1750-8568 (Online) Murchison in the Welsh Marches: a History of Geology Group field excursion led by John Fuller, May 8th – 10th, 1998 John Fuller1 and Hugh Torrens2 FULLER, J.G.C.M. & TORRENS, H.S. (2010). Murchison in the Welsh Marches: a History of Geology Group field excursion led by John Fuller, May 8th – 10th, 1998. Proceedings of the Shropshire Geological Society, 15, 1– 16. Within the field area of the Welsh Marches, centred on Ludlow, the excursion considered the work of two pioneers of geology: Arthur Aikin (1773-1854) and Robert Townson (1762-1827), and the possible train of geological influence from Townson to Aikin, and Aikin to Murchison, leading to publication of the Silurian System in 1839. 12 Oak Tree Close, Rodmell Road, Tunbridge Wells TN2 5SS, UK. 2Madeley, Crewe, UK. E-mail: [email protected] "Upper Silurian" shading up into the Old Red Sandstone above, and a "Lower Silurian" shading BACKGROUND down into the basal "Cambrian" (Longmynd) The History of Geology Group (HOGG), one of below. The theoretical line of division between his the specialist groups within the Geological Society Upper and Lower Silurian ran vaguely across the of London, has organised a number of historical low ground of Central Shropshire from the trips in the past. One was to the area of the Welsh neighbourhood of the Craven Arms to Wellington, Marches, based at The Feathers in Ludlow, led by and along this line the rocks and faunas of the John Fuller in 1998 (8–10 May). -

Proposed Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark

Great things to see and do in the Proposed Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark Project The layers lying above these are grey muddy Welcome to the world-class rocks that contain seams of ironstone, fireclay heritage which is the Black and coal with lots of fossils of plants and insects. These rocks tell us of a time some 310 million Country years ago (called the Carboniferous Period, The Black Country is an amazing place with a named after the carbon in the coal) when the captivating history spanning hundreds of Black Country was covered in huge steamy millions of years. This is a geological and cultural rainforests. undiscovered treasure of the UK, located at the Sitting on top of those we find reddish sandy heart of the country. It is just 30 minutes from rocks containing ancient sand dunes and Birmingham International Airport and 10 minutes pebbly river beds. This tells us that the landscape by train from the city of Birmingham. dried out to become a scorching desolate The Black Country is where many essential desert (this happened about 250 million years aspects of the Industrial Revolution began. It ago and lasted through the Permian and Triassic was the world’s first large scale industrial time periods). landscape where anything could be made, The final chapter in the making of our landscape earning it the nick-name the ‘workshop of the is often called the’ Ice Age’. It spans the last 2.6 world’ during the Industrial Revolution. This million years of our history when vast ice sheets short guidebook introduces some of the sites scraped across the surface of the area, leaving and features that are great things to see and a landscaped sculpted by ice and carved into places to explore across many parts of The the hills and valleys we see today. -

Wildlife Panel Minutes of the Meeting Held on 6 March 2019

Wildlife Panel Minutes of the meeting held on 6 March 2019 In attendance: Johnny Birks, Ann Bowker, Peter Garner, Nigel Hand, Charlie Long, Mel Mason, Pete Watson, Duncan Westbury, Helen Woodman + Andy Pearce, Simon Roberts, Jonathan Bills 1. Appointment of Chair. Jonathan Bills welcomed all to the meeting. Pete Watson was elected as chair for 2019. 2. Apologies were received from: Alison Uren, Peter Holmes, John Michael, Helen Stace, Katey Stephen. 3. Matters arising from the previous meeting: Woodland works — JBiIIs stated how useful last year’s outdoor meeting had been hearing the Panel’s thoughts on woodland management that would be of benefit to currently unmanaged foothill woods. This advice has subsequently been incorporated into Malvern Hills Trust’s (MHT) Countryside Stewardship agreement and work is unden/vay. New panel members — at the last meeting it was agreed that, following the loss of several panel members, we should recruit more members, especially a person with knowledge on invertebrates. Three people have been invited to join — Charlie Long, V\fi|| Watson and Richard Comont. Richard and Charlie have agreed to join and no reply has been received from V\fi||. ACTION — JBiIIs to provide info to new members and add them to the email list. 4. Verbal report of last year’s two outdoor meetings was given by Peter Garner. Peter summarised the visits to Central Hi||s woodlands and a glow- worm search and felt they were most interesting and worthwhile. 5. Reports and recommendations from the Panel. Reports on the various taxa and related projects were given by Panel members. -

L02-2135-02B-Intervisibilty B

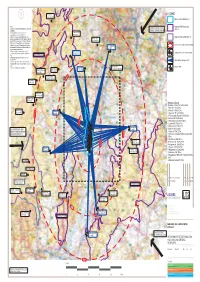

LEGEND Pole Bank 516m AOD (NT) Malvern Hills AONB (Note 3) Notes: Adjacent AONB boundaries LONGER DISTANCE VIEWS 1. Base taken from A-Z Road Maps for Birmingham (Note 3) and Bristol FROM BEYOND BIRMINGHAM 2. Viewpoints have been selected to be Brown Clee Hill representative, and are not definitive 540m AOD 3. Taken from www.shropshirehillsaonb.co.uk Adjacent National Park (Note 7) website, www.cotswoldaonb.com website, Malvern Kinver Edge Hills District Council Local Plan Adopted 12th July 155m AOD (NT) 2006, Forest of Dean District Local Plan Review 30km Distance from spine of Malvern Hills Adopted November 2005, Herefordshire Unitary Clent Hills 280m Development Plan Adopted 23rd March 2007 and AOD (NT) wyevalleyaonb.org.uk website 4. Observer may not nessecarily see all of Titterstone Clee 10 intervening land between viewpoint and Malvern 1 Viewpoint used as visual receptor SHROPSHIRE AONB Hill 500m AOD Hills 14 5. Information obtained from the Malvern Hill Conservators Intervisibility viewing corridor 6. Views outside inner 15km study area graded on Appendix Table 1, but not shown graded on plan L02. M5 alongside 7. Taken from OS Explorer MapOL13. Clows Top Malvern Hills High Vinnals 11 Bromsgrove 100m AOD Harley’s Mountain 231m AOD A 370m AOD 50km 386m AOD Bircher Common 160-280m AOD (NT) Hawthorn Hill 30km 407m AOD Bradnor Hill 391m AOD (NT) Hergest Ridge 426m AOD Malvern Hills (Note 4) 22 peaks including from north to south: A-End Hill 1079ft (329m) 41 Glascwn Hill Westhope B-North Hill 1303ft (397m) 522m AOD Hill 120m C-Sugarloaf -

Annual Report 1998

HEREFORDSHIRE ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB ~AKER TILLY NNUAL BIRD REPORT 1998 Volume 5 Number 8 £5.00 HEREFORDSHIRE ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB ANNUAL REPORT 1998 Founded 1950 Volume 5 Number 8 Edited by Paul Downes Published October 1999 by Herefordshire Ornithological Club Price £5.00 Illustrations by Paul Downes Copyright - HOC 1999 HEREFORDSHIRE ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB ANNUAL REPORT 1998 Volume 5 Number 8 CONTENTS Officers and Committee 1998 .492 Editor's Report 1998 .493 Club Meetings Held in 1998 .495 Weather Report 1998 - Bob Bishop .497 Bird Calendar 1998 - Paul Downes 500 Ringing Report 1998 - Paul Scriuen 503 Herefordshire Nature Trust Nestbox Scheme 1998 - C. W Sheldrake 506 County Surveys 507 The HOC and Titley Court Farm - Peter Eldridge 509 The Herefordshire Garden Birdwatch - Ray Mellish 510 Tars Coppice 1998 -Anne Russell 511 Systematic List 1998 513 Escapes 558 List of Contributors to Systematic List 1998 559 County Locations 560 Earliest and Latest Dates for Summer Migrants 1998 562 Latest and Earliest Dates for Winter Migrants 1998 562 White Stork at Bridge Sollars - Paul Downes 563 Red-necked Phalarope at Wellington Gravel Pits - Paul Downes 565 County Bird List for Herefordshire 567 Herefordshire County Rarities 570 Report Exchanges 571 Affiliated Associaions 571 Income and Expenditure Account 572 "All maps based upon the Ordnance Survey Map with the permission of The Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright. C4/85-88" HEREFORDSHIRE ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB Founded 1950 OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1998 President Vice-President J. Vickerman Mrs J. M. Bromley Chairman Vice-Chairman J. R. Pullen G. R. Parker Hon. Secretary I. B. Evans 12, Brockington Drive, Tupsley, Hereford, HR1 1TA Tel: 01432 265509 Hon.