Wellington Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 104. South Herefordshire and Over Severn Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Wildlife Panel Minutes of the Meeting Held on 6 March 2019

Wildlife Panel Minutes of the meeting held on 6 March 2019 In attendance: Johnny Birks, Ann Bowker, Peter Garner, Nigel Hand, Charlie Long, Mel Mason, Pete Watson, Duncan Westbury, Helen Woodman + Andy Pearce, Simon Roberts, Jonathan Bills 1. Appointment of Chair. Jonathan Bills welcomed all to the meeting. Pete Watson was elected as chair for 2019. 2. Apologies were received from: Alison Uren, Peter Holmes, John Michael, Helen Stace, Katey Stephen. 3. Matters arising from the previous meeting: Woodland works — JBiIIs stated how useful last year’s outdoor meeting had been hearing the Panel’s thoughts on woodland management that would be of benefit to currently unmanaged foothill woods. This advice has subsequently been incorporated into Malvern Hills Trust’s (MHT) Countryside Stewardship agreement and work is unden/vay. New panel members — at the last meeting it was agreed that, following the loss of several panel members, we should recruit more members, especially a person with knowledge on invertebrates. Three people have been invited to join — Charlie Long, V\fi|| Watson and Richard Comont. Richard and Charlie have agreed to join and no reply has been received from V\fi||. ACTION — JBiIIs to provide info to new members and add them to the email list. 4. Verbal report of last year’s two outdoor meetings was given by Peter Garner. Peter summarised the visits to Central Hi||s woodlands and a glow- worm search and felt they were most interesting and worthwhile. 5. Reports and recommendations from the Panel. Reports on the various taxa and related projects were given by Panel members. -

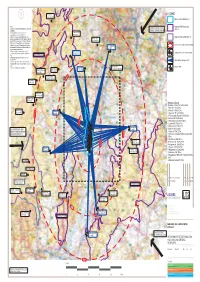

L02-2135-02B-Intervisibilty B

LEGEND Pole Bank 516m AOD (NT) Malvern Hills AONB (Note 3) Notes: Adjacent AONB boundaries LONGER DISTANCE VIEWS 1. Base taken from A-Z Road Maps for Birmingham (Note 3) and Bristol FROM BEYOND BIRMINGHAM 2. Viewpoints have been selected to be Brown Clee Hill representative, and are not definitive 540m AOD 3. Taken from www.shropshirehillsaonb.co.uk Adjacent National Park (Note 7) website, www.cotswoldaonb.com website, Malvern Kinver Edge Hills District Council Local Plan Adopted 12th July 155m AOD (NT) 2006, Forest of Dean District Local Plan Review 30km Distance from spine of Malvern Hills Adopted November 2005, Herefordshire Unitary Clent Hills 280m Development Plan Adopted 23rd March 2007 and AOD (NT) wyevalleyaonb.org.uk website 4. Observer may not nessecarily see all of Titterstone Clee 10 intervening land between viewpoint and Malvern 1 Viewpoint used as visual receptor SHROPSHIRE AONB Hill 500m AOD Hills 14 5. Information obtained from the Malvern Hill Conservators Intervisibility viewing corridor 6. Views outside inner 15km study area graded on Appendix Table 1, but not shown graded on plan L02. M5 alongside 7. Taken from OS Explorer MapOL13. Clows Top Malvern Hills High Vinnals 11 Bromsgrove 100m AOD Harley’s Mountain 231m AOD A 370m AOD 50km 386m AOD Bircher Common 160-280m AOD (NT) Hawthorn Hill 30km 407m AOD Bradnor Hill 391m AOD (NT) Hergest Ridge 426m AOD Malvern Hills (Note 4) 22 peaks including from north to south: A-End Hill 1079ft (329m) 41 Glascwn Hill Westhope B-North Hill 1303ft (397m) 522m AOD Hill 120m C-Sugarloaf -

Passed Walks Programmes

WALKING INFORMATION FOR WEDNESDAY AND THURSDAY WALKING GROUPS 2014 DATE LEADER WALK INFORMATION WE MEET AT THE BRIDGE STREET SPORTS CENTRE CAR PARK AT 0930 UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED WEDNESDAY WALKING GROUP -- 5 TO 7 MILES: THE DAY AFTER THE MAIN U3A MEETING 22ND JAN. 19th FEB. 19TH MARCH HEATHER/RICHARD STOKESAY. 6.25 MILES. MAYBE REFRESHMENTS AT CAFÉ IN CASTLE. TAKE A PACKED LUNCH 16TH APRIL DAVID WEOBLEY, GARNSTONE WOOD, BURTON HILL. GOOD FOR BLUEBELLS. 6 MILES. TAKE A PACKED LUNCH 21ST MAY MIKE ORLETON, WYSON COMMON, HEREFORDSHIRE TRAIL. 6 MILES. TAKE A PACKED LUNCH 18TH JUNE JOHN CRAVEN ARMS TO LOWER DINCHOPE, FLOUNDERS FOLLY, AND HALFORD. THERE ARE 2 CLIMBS OF 100 & 135 METRES. 6.5 MILES. TAKE LUNCH 16TH JULY MIKE BODENHAM, MARCHES WAY, AND DODENHAM MOOR. 6 MILES. TAKE A PACKED LUNCH 20TH AUG. RICHARD/BARBARA CRAVEN ARMS, HOPESAY. 7 MILES. 10:07 TRAIN FROM LEO. OR 10:00 AT COMM. CENTRE. RENDEZVOUS CRAVEN TRN. STN. 10:30. TAKE LUNCH 17TH SEPT. DAVID BOCKLETON, CADMORE BROOK, AND FISHPOOL COTTAGES. 6.4 MILES. A LITTLE BIT HILLY BUT THE VIEWS ARE GREAT. TAKE A PACKED LUNCH 22ND OCT. MIKE "WATER BREAK ITS NECK" NEAR NEW RADNOR. 7 MILES, MODERATE, SOME HILLS, WATERFALL, AND SUPURB VIEWS. TAKE A PACKED LUNCH 19TH NOV. RICHARD DRIVE TO KINGTON, THEN BUS 41 AT 1010 TO TITLEY MONUMENT, WALK BACK TO KINGTON ON BEAUTIFUL PATHS. 6 MILES. TAKE LUNCH 17TH DEC. WILL/WENDY A SHORT WALK TO CELEBRATE OUR YEAR OF WALKING. DRINKS ETC. AT A LOCAL CAFÉ THURSDAY WALKING GROUP -- 3 TO 4 MILES: THE FIRST THURSDAY IN THE MONTH 2ND JAN. -

People... Heritage... Belief VISIT HEREFORDSHIRE CHURCHES

Visit HEREFORDSHIRE CHURCHES 2018-2019 www.visitherefordshirechurches.co.uk St Margarets People... Heritage... Belief VISIT HEREFORDSHIRE CHURCHES Churches tell a story, many stories - of families, of political intrigue and social change, of architecture, and changes in belief. Herefordshire Churches Tourism Group is a network of some of the best churches and chapels in the county that Wigmore have dominated the landscape and life of communities for more than a thousand years. What will you find when you enter the door? A source of fascination, awe, or a deep sense of peace? Here people have come and still come, generation on generation, seeking the place of their ancestors or solace for the present. Our churches still play a significant part in the life of our communities. Some act as community centres with modern facilities, others have developed their churchyards to attract wild life, all serve as living monuments to our heritage and history. Visiting our churches Mappa Mundi can enhance your appreciation and enjoyment of Herefordshire. Come and share. Shobdon Mappa Mundi, one of the world’s unique medieval treasures, Hereford Cathedral. Reproduced by kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Hereford and the Mappa Mundi Trustees. www.visitherefordshirechurches.co.uk Parking Disabled WC Refreshments Hereford Cathedral PASTORAL HEREFORD CITY Herefordshire is one of England’s most rural, natural, peaceful and relaxing counties with Belmont Abbey an abundance of lovely places to stay; local food and drink; things to do and explore every season of the year. Hereford is the historic cathedral city of Herefordshire and lies on the River Wye with fine walks along the river bank and a wide range of places to eat and drink. -

Land Management Plan Part 3: Vision, Objectives and Work Programme

MHT LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN PART 3: VISION, OBJECTIVES AND WORK PROGRAMME Parts 1 and 2 have identified what is present on the MHT holding, what is most important, what MHT would ideally achieve and the factors present. Using the preceding sections, Part 3 draws up a picture of what we want to achieve (guiding principles and objectives) and prescribes the tasks necessary to help get there over the next 5 years (work programme). 63 Contents of Part 3: 3.1 Vision, Guiding Principles and Objectives Page 65 3.2 Objectives for features & qualities Page 68 Objective 1: Landscape character Page 68 Objective 2: Earth heritage Page 69 Objective 3: Herefordshire Beacon Camp Page 70 Objective 4: The Shire Ditch & burial mounds Page 71 Objective 5: Listed buildings and structures Page 72 Objective 6: Public access Page 72 Objective 7: Broad-leaved Woodland Page 74 Objective 8: Acid grassland with heath Page 75 Objective 9: Neutral grasslands Page 77 Objective 10: Calcareous grasslands Page 78 Objective 11: Mire and bog Page 78 Objective 12: Adder Page 79 Objective 13: Grayling Page 80 Objective 14: Ponds Page 81 3.3 Work Programme Whole holding Pages 83-87 Management units map Page 88 Zone 1 Northern Hills Pages 90-96 Zone 2 Central Hills Pages 98-104 Zone 3 Southern Hills Pages 106-122 Zone 4 Hollybed Common Pages 124-128 Zone 5 Castlemorton Common Pages 130-133 Zone 6 Enclosed Lowlands Colwall Green, Bowling Green meadow and the roadside verges Pages 134-179 Zone 7 Old Hills Pages 180-184 Zone 8 Wells, Malvern and Link Commons Pages 186-191 3.4 Projects Plan Pages 192-194 64 3.1 Vision and Guiding Principles Part 2 identified MHT’s ideal outcomes for the landscape. -

KINGTON AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2019-2031 Kington Town Kington Rural and Lower Harpton Group Parish Huntington Parish

KINGTON AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2019-2031 Kington Town Kington Rural and Lower Harpton Group Parish Huntington Parish KINGTON AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2019-2031 1 Contents Page 1. What is a Neighbourhood Plan? 3 2. The Kington Area Neighbourhood Plan 4 3. Aims of the Kington Area Neighbourhood Plan 5 4. Description of the Neighbourhood Plan Area 6 5. Development Requirements 13 6. Kington Area Neighbourhood Plan Local Issues 17 7. Vision Statement 19 8. Kington Area Neighbourhood Plan Objectives 20 9. Kington Neighbourhood Plan Policies 22 KANP ENV 1: A Valued Natural Environment 22 KANP ENV 2: Dark Skies 23 KANP ENV 3: A Valued Built Environment 26 KANP SB1: Settlement Boundaries 29 KANP H1: Housing Delivery Kington Town 36 KANP H2: Housing Delivery Land South of Kington 40 KANP H3: Housing Delivery: Kington Rural and 45 Lower Harpton Group Parish KANP H4: Housing Delivery: Huntington Parish 49 KANP H5: Housing Design Criteria 50 KANP E1: A Thriving Rural Economy 52 KANP E2: Large Scale Employment Activities 53 KANP KTC 1: Kington Town Centre 57 KANP T1: Sustainable Tourism and Leisure 61 KANP INF1: Local Infrastructure 63 KANP LGS1: Green Spaces 67 KANP G1: Green Infrastructure 68 KANP CF1: Community Facilities 71 10. Community Projects 72 11. Review and Monitoring the Plan 73 Appendices: 75 Photographs by A. Compton, R. Cotterill and J.Gardner KINGTON AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2019-2031 2 1 WHAT IS A NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN? 1. In 2011 Parliament agreed the Localism Act which devolved a number of powers to local communities including direct involvement in strategic planning. -

The Worcestershire Beacon Race Walk

The Worcestershire Beacon Race Short Walk The Worcestershire Beacon Race Walk This is an abridged version of walk 5, taken from the ‘Pictorial Guide to the Malvern Hills’ Book Two: Great Malvern. This walk seeks to avoid where ever possible very steep slopes and steps. However, this is a walk on the Malvern Hills and this means there is no avoiding some fairly tough sections along the walk. Copies of the book are available from the Tourist Information Centre, Malvern Book Co- operative, Malvern Gallery, Malvern Museum and Malvern Priory. Priced £8.50 This 5 mile circular walk mostly follows the route of the Worcestershire Beacon Race and provides an interesting, if strenuous, route from Rose Bank Gardens via St Ann’s Well, past the Goldmine and up to the summit of the Worcestershire Beacon. After soaking up the incredible panorama of the Herefordshire and Worcestershire countryside the return journey circumnavigates North Hill before returning to Great Malvern. Allow a whole morning or afternoon for this scenic walk, or if enjoying refuelling stops probably 5 hours is nearer the mark. Turn right out of the Abbey hotel passing through the Priory Gatehouse and as the Post Office is reached, take the sharp left up to the Wells Road with Belle Vue Terrace to the right. Taking care at this junction of the busy Wells Road cross-over to the entrance of Rose Bank Gardens with Malvern’s newest sculpture the eye catching ‘Buzzards’. Belle Vue Terrace Shops 1 The Worcestershire Beacon Race Short Walk Every year since 1953, on the second Saturday in October, Malvern’s most popular running event, the Worcestershire Beacon Race takes place from the Rose Bank Gardens next to the Mount Pleasant Hotel (Map Reference SO 7746 4577). -

Great Malvern Circular Or from Colwall)

The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular) The Malvern Hills (Colwall to Great Malvern) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 20th July 2019 21st July 2019 Current status Document last updated Monday, 22nd July 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular or from Colwall) Start: Great Malvern Station or Colwall Station Finish: Great Malvern Station Great Malvern station, map reference SO 783 457, is 11 km south west of Worcester, 165 km north west of Charing Cross, 84m above sea level and in Worcestershire. Colwall station, map reference SO 756 424, is 4 km south west of Great Malvern, 25 km east of Hereford, 129m above sea level and in Herefordshire. -

20Th-23Rdseptember 2018

20 th -23 rd September 2018 www.kingtonwalks.org T 07752 087786 WElCOME TO KingTOn WalKs 2018 Our sEvEnTh fEsTival ingTOn is one of the great small market towns of Britain. situated close to the Welsh border it was for centuries a centre Kfor cattle drovers, so a web of footpaths and byways, accessible on foot from the town centre await discovery by present day walkers. The Offa's Dyke Path national Trail, the herefordshire Trail, Mortimer Trail from ludlow, and the Wyche Way from Broadway all pass through (or start/finish) in the town. Welcome to our seventh annual festival. This year the programme is as extensive as ever with walks covering history, natural history, geology, industry, landscapes and a pub or two. This year, in additon to some old favourites, we have introduced many new walks including a creative walk around Kington, a nordic Walk over hergest ridge to gladestry, a walk from the masterpiece of English rococo shobdon Church and many more. We are opening the year's festival on Thursday night with a Tagine Evening provided by David Pickersgill of Weobley ash. saturday night will feature the Whiskey river Band at the Burton hotel with their inimitable brand of Cajun, Blues and Country music. no matter how far you have walked, it is impossible to sit still! Due to a clash with several other national events, we have decided to stage the eight peaks Challenge on 15th of September (the weekend before the main festival). Kington Walks is a charity registered in England and Wales (1172022). -

Newsletter No. 248 April 2018

NewsletterNewsletter No.No. 248248 AprilApril 20182018 Contents: Future Programme 2 Other Societies and Events 4 Committee AGM Report 6 Chairman Editorial 7 Graham Worton More on the Brierley Hill Road Cutting 8 Vice Chairman Andrew Harrison Field Report: South Malverns 10 Hon Treasurer Geoconservation Reports: Alan Clewlow Barrow Hill, Saltwells, Wren's Nest 12 Hon Secretary Robyn Amos The Abberley and Malvern Hills Geopark 14 Field Secretary Mike's Musings No.14: Andrew Harrison Disasters are nothing new! 15 Meetings Secretary Vacant Members' Forum: Newsletter Editor UK Onshore Geophysical Library 16 Julie Schroder Social Media Déjà vu? - read on! Peter Purewal Webmaster John Schroder Other Members Christopher Broughton Bob Bucki Dave Burgess Copy date for the next Newsletter is Friday 1 June Newsletter No. 248 The Black Country Geological Society April 2018 Robyn Amos, Andy Harrison, Julie Schroder, Honorary Secretary, Field Secretary, Newsletter Editor, 42 Billesley Lane, Moseley, ☎ ☎ 07595444215 Mob: 07973 330706 Birmingham, B13 9QS. ☎ 0121 449 2407 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] For enquiries about field and geoconservation meetings please contact the Field Secretary. To submit items for the Newsletter please contact the Newsletter Editor. For all other business and enquiries please contact the Honorary Secretary. For further information see our website: bcgs.info, Twitter: @BCGeoSoc and Facebook. Future Programme Indoor meetings will be held in the Abbey Room at the Dudley Archives, Tipton Road, Dudley, DY1 4SQ, 7.30 for 8.00 o'clock start unless stated otherwise. Visitors are welcome to attend BCGS events but there will be a charge of £1.00.