Instructor's Manual CREATED EQUAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

Journal – Winter 2002

VOL. VII, NO. 2 WINTER 2002 A NEWSLETTER FOR THE MEMBERS OF THE JUNIOR LEAGUE OF MIAMI, INC. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2002 A Race to Remember Inn Transition By Andria Hanley South The Junior League of Miami filled with energy, support, emotion and time with Ribbon Cutting came out in force to support family and friends; a time to salute those who have the Race for the Cure. More survived the disease and honor those taken because than 75 registration forms of it. The sea of pink shirts made their way to the Tuesday, December 10 were submitted in an effort to stage to stand proud, and to take in all the en- 11:00 a.m. support the Komen Founda- couragement that surrounded them at Bayfront tion, which leads the fight to find a cure for breast Park early that Saturday morning. Come celebrate 10 cancer. This year, more than 203,000 women will Shortly after the survivor ceremony, all participants years of Women be diagnosed with breast cancer. made their way to start the race, outlined by an Building Better The day started early, some women were there be- arc of pink balloons. Some ran, some walked, but Communities as we fore the sun came up, preparing for a morning all made their way to the finish line and were cheered on by fans and friends. open the doors to this amazing new The Junior League of Miami made a difference that day, supporting the women in our commu- facility nity who have faced or will face this disease. -

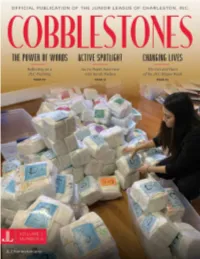

Cobblestones

COBBLESTONES Cobblestones is a member-driven, TABLE OF mission-focused publication that highlights the Junior League of Charleston—both its members and its community partners—through CONTENTS engaging stories using quality design and photography. LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT 5 JLC TRAINING EDITOR + PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE CHAIR: EDUCATION Casey Vigrass 975 Savannah HWY Suite #105 (843) 212-5656 [email protected] 10 PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE 12 PROVISIONAL SPOTLIGHT ASSISTANT CHAIR: Liz Morris SUSTAINER SPOTLIGHT 13 PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Lizzie Cook PRESIDENT SPOTLIGHT Ali Fox 17 Catherine Korizno GIVING BACK DESIGN + ART DIRECTION: 20 06 Brian Zimmerman, Zizzle WOMEN'S SUFFERAGE ACTIVE SPOTLIGHT: COVER IMAGE: SARAH NIELSEN Featuring Alle Farrell 14 Restore. Do More. CHARLESTON RECEIPTS 18 Cryotherapy Whole Body Facials Local CryoSkin Slimming Toning Facials 08 Infrared Sauna IV Drip Therapy The Forward- Thinking Mindset Photobiomodulation (PBM) IM Shots of a Junior League Founder Stretch Therapy Micronutrient Testing DIAPER BANK Compression Therapy Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Book your next event with us! 26 24 VOLUME 1 | NUMBER 6 3 FROM THE EDITOR FROM THE PRESIDENT “We have the responsibility to act and the opportunity to conscientiously act to affect Passionate. Hard-working. Unstoppable. the environment around us.” – Mary Harriman Rumsey, Founder of the Junior League These words, spoken about the Junior League of Charleston, have described our Recently, I was blessed by the opportunity to attend Organizational Development -

Woodside World

Mar 5, 2021 Vol. LXXIX Issue 5 Woodside World NEWS of CONGREGATION and COMMUNITY Joyfully Defiant for the Sake of a Just World a congregation of the United Church of Christ, the Alliance of Baptists, and the American Baptist Churches witness to the fire at the Triangle residency, two-thirds of whom only for straight people, born of From the Pastor Shirtwaist Factory in 1911, which were Jews, and 231,884 foreign the grief of a widow who would Pastor Deb was asked by Michigan killed 146 people, mostly young ‘visitors’” (Downey 194). not be eligible for her partner's Conference UCC to write an essay for Women's History Month. This is her women and girls locked into the But she was disliked by labor benefits. contribution. building to prevent them from leaders — men who didn’t think Perkins died in 1965. In 1980, taking unauthorized breaks. She In a book review in East Village women should have cabinet on her 100th birthday, the was 30 years old; the sight of the posts. She was disparaged as Department of Labor Building Magazine last week, Frances inferno and its victims changed Perkins was quoted having a a communist sympathizer, as in DC (c 1934) was named the her, became an impetus for her a radical leftist, as a lesbian. Frances Perkins Building. Trivia: fight with the head of General life’s work. Motors, which made me a fan Worth noting that Roosevelt did Michigan Senator Carl Levin even before I knew anything When the stock market crashed not defend her and kept other was principal sponsor of the else. -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Special Collections Libraries University of Georgia Index 1. Legal Treatises. Ca. 1575-2007 (29). Age of Enlightenment. An Awareness of Social Justice for Women. Women in History and Law. 2. American First Wave. 1849-1949 (35). American Pamphlets timeline with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. American Pamphlets: 1849-1970. 3. American Pamphlets (44) American pamphlets time-line with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. 4. American Pamphlets. 1849-1970 (47). 5. U.K. First Wave: 1871-1908 (18). 6. U.K. Pamphlets. 1852-1921 (15). 7. Letter, autographs, notes, etc. U.S. & U.K. 1807-1985 (116). 8. Individual Collections: 1873-1980 (165). Myra Bradwell - Susan B. Anthony Correspondence. The Emily Duval Collection - British Suffragette. Ablerta Martie Hill Collection - American Suffragist. N.O.W. Collection - West Point ‘8’. Photographs. Lucy Hargrett Draper Personal Papers (not yet received) 9. Postcards, Woman’s Suffrage, U.S. (235). 10. Postcards, Women’s Suffrage, U.K. (92). 11. Women’s Suffrage Advocacy Campaigns (300). Leaflets. Broadsides. Extracts Fliers, handbills, handouts, circulars, etc. Off-Prints. 12. Suffrage Iconography (115). Posters. Drawings. Cartoons. Original Art. 13. Suffrage Artifacts: U.S. & U.K. (81). 14. Photographs, U.S. & U.K. Women of Achievement (83). 15. Artifacts, Political Pins, Badges, Ribbons, Lapel Pins (460). First Wave: 1840-1960. Second Wave: Feminist Movement - 1960-1990s. Third Wave: Liberation Movement - 1990-to present. 16. Ephemera, Printed material, etc (114). 17. U.S. & U.K. -

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a Nurse Researcher Transformed Nursing Theory, Nursing Care, and Nursing Education

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a nurse researcher transformed nursing theory, nursing care, and nursing education • Moved nursing practice beyond the patient to include care of families and the elderly • First nurse and first woman to serve as Deputy Surgeon General Bella Abzug 1920 – 1998 • As an attorney and legislator championed women’s rights, human rights, equality, peace and social justice • Helped found the National Women’s Political Caucus Abigail Adams 1744 – 1818 • An early feminist who urged her husband, future president John Adams to “Remember the Ladies” and grant them their civil rights • Shaped and shared her husband’s political convictions Jane Addams 1860 – 1935 • Through her efforts in the settlement movement, prodded America to respond to many social ills • Received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 Madeleine Korbel Albright 1937 – • First female Secretary of State • Dedicated to policies and institutions to better the world • A sought-after global strategic consultant Tenley Albright 1934 – • First American woman to win a world figure skating championship; triumphed in figure skating after overcoming polio • First winner of figure skating’s triple crown • A surgeon and blood plasma researcher who works to eradicate polio around the world Louisa May Alcott 1832 – 1888 • Prolific author of books for American girls. Most famous book is Little Women • An advocate for abolition and suffrage – the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts in 1879 Florence Ellinwood Allen 1884 – 1966 • A pioneer in the legal field with an amazing list of firsts: The first woman elected to a judgeship in the U.S. First woman to sit on a state supreme court. -

Verdi's Life and Art Rediscovering Gershwin the University Press Humanities Editor's Notes

NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES • VOLUME 8 NUMBER 3 • MAY/JUNE 1987 Verdi's Life and Art Rediscovering Gershwin The University Press Humanities Editor's Notes Musicology Located unobtrusively within the Endowment's standard definition of the humanities is the phrase “history, theory, and criticism of the arts." It is here that musicology finds its niche as a relative newcomer. Most of the im portant texts in music were not generally available as musical scores until the 1950s, writes Joseph Kerman in Contemplating Music. "Readers who are acquainted with other fields of research—in literature or art, history or sci ence—may find it difficult to appreciate the primitive state of musical docu Patrons in the Music Division of the Library mentation in the 1950s___Dozens of Haydn symphonies were published in of Congress "read" the literature of music by score for the first time in this period, as well as minor works by Beethoven examining program notes on the record sleeve and listening to a recorded performance. Be and practically the whole corpus of music by important secondary figures of the hind them is a page from the autograph man Renaissance and Baroque eras___" "(emphasis in original) uscript of the opera Ernani by Giuseppe This issue of Humanities offers several essays on the study of music— Verdi. (Manuscript: University of Chicago both for those who limit its scope to the study of the history of Western art Press. Library photograph: Morton Broffman) music and for those who expand that definition to include ethnomusicology and the study of modern American compositions. -

Mary Harriman Rumsey, Beta Epsilon, Founded the First Junior League Chapter in New York in 1901

March 2011 March has been designated as Women’s History Month. Who are some notable Kappas of whom we should be aware? Mary Harriman Rumsey, Beta Epsilon, founded the first Junior League chapter in New York in 1901. Since its founding, the organization has spread to virtually every large city in the United States. Inspired by a lecture on the settlement movement, Mary, along with several friends, began volunteering at the College Settlement on Rivington Street in New York City's Lower East Side, a large immigrant enclave. Through her work at the College Settlement, Mary became convinced that there was more she could do to help others. Subsequently, Mary and a group of 80 debutantes established the Junior League for the Promotion of Settlement Movements in 1901, while she was still a student at Barnard College. The purpose of the Junior League was to unite interested debutantes in joining the Settlement Movement in New York City. As word of the work of the young Junior League women in New York spread, women throughout the country and beyond formed Junior Leagues in their communities. In time, Leagues would expand their efforts beyond settlement house work to respond to the social, health and educational issues of their respective communities. In 1921, approximately 30 Leagues banded together to form the Association of Junior Leagues of America to provide support to one another. With the creation of the Association, it was Mary who insisted that, although it was important for all Leagues to learn from one another and share best practices, each League was ultimately beholden to their respective community and should thus function to serve that community’s needs. -

JUNIOR LEAGUE of GREATER WINTER HAVEN Women Building Better Communities

JUNIOR LEAGUE OF GREATER WINTER HAVEN Women building better communities JUNIOR LEAGUE OF GREATER WINTER HAVEN Promoting Volunteerism, Developing the Potential of Women, Improving the Community Board Members 2016-17 President Jennifer Schaal President-Elect Anna Bostick Membership Vice President Aleah Pratt Finance Vice President Courtney Pate Finance Vice President Elect Ashley Adkinson Communications Vice President April Ann Spaulding Community Vice President Leigh-Anne Pou Provisional Class Chair Christi Holby Community Research & Project Development Allison Futch Fund Development Rhonda Todd Past President & Sustainer Liaison Katie Barris MISSION The Junior League of Greater Winter Haven, Inc. is an organization of women committed to promoting volunteerism, developing the potential of women, and to improving the community through the effective action and leadership of trained volunteers. Its purpose is exclusively education- al and charitable. FUTURE VISION The Junior League of Greater Winter Haven, Inc. will be recognized as a civic leader that effectively impacts our community individually and collectively. With a pioneering spirit, the Junior League of Greater Winter Haven will work to meet the needs of our community through trained volunteers, education, funding and collaboration. OUR COMMITMENT The Junior League of Greater Winter Haven Inc. welcomes all women who value our Mission. We are committed to an inclusive environment of diverse individuals. 3 AJLI Finance Report Junior League Legacy The Junior League of Greater 6/1/16-5/31/16 Over the years, The Junior League has had a profound effect on what Winter Haven is one of the it means to live in modern society. The League experience cultivates 293 leagues with membership women into thoughtful and seasoned leaders and teaches them how to Net Fundraiser Income - $21,252.40 take on the toughest problems of the day and work collaboratively with in the Association of Junior • Light up the Lanes - $5,639 Leagues International, Inc. -

The Ghost in the Machine: Frances Perkins' Refusal to Accept Marginalization

THE GHOST IN THE MACHINE: FRANCES PERKINS’ REFUSAL TO ACCEPT MARGINALIZATION A THESIS in History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas city in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS By Patrick French B.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2011 Kansas City, Missouri 2014 © 2014 PATRICK FRENCH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE GHOST IN THE MACHINE: FRANCES PERKINS’ REFUSAL TO ACCEPT MARGINALIZATION Patrick French, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2014 ABSTRACT Frances Perkins was the United States Secretary of Labor from 1933-1945, yet she has received little attention from historians. There are countless works that study President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s years in office, but Perkins’ achievements have yet to enter the mainstream debate of New Deal scholarship. Perkins did not “assist” with the New Deal; she became one of the chief architects of its legislation and a champion of organized labor. Ever mindful of her progressive mentor, Florence Kelley, Perkins stared her reform work at Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago. By the end of FDR’s tenure as president, the forty-hour workweek became standard, child labor was abolished, and she was instrumental in the work-relief programs under the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the popular Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and most notably Section 7a of the National Industrial Recovery Administration that allowed for collective bargaining for organized labor. FDR’s controversial appointment marked the first time a female had attained such a powerful position in government, and she wrestled with cross-sections of class, gender, and ethnicity during her tenure as FDR’s Labor Secretary. -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Subject Image Description Author Publisher, date Item Type Pro/Con Country The Delineator, Jan 1910; pgs. 37, 38, 70; Daggett, Mabel Potter; "Suffrage Enters the Women's Suffrage Baggett, Mabel Potter The Delineator, 1910 Article Pro US Drawing Room."; 39 x 26 cm Harper's Weekly, July 25, 1914, back of cover page; Fisher, Katharine Rolston; "The 'Anti' Women's Suffrage Fisher, Katharine Rolston Fisher, Katharine Rolston, 1914 Article Con US Speaks"; 34 x 19 cm Harper's Weekly, n.d., pg. 8; Brooks, Sydney, London Correspondent for Harper's Weekly; Women's Suffrage Brooks, Sydney Harper's Weekly Article Con US "The Conquest of the English Channel"; 38 x 24 cm The Illustrated American, May 19, 1894, pgs. 577, 578; "Shall Women be Granted Full Women's Suffrage Suffrage?"; 30 x 22 cm The Illustrated American, 1894 Article Pro US Lucy Hargrett Draper Center Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law The Ladies' Home Journal, January 1921, pgs. 20, 78, 81; Jordan, Elizabeth; "The Big Things for Women's Suffrage Women in Politics: Employ the Ballot Early and Often for Your Community's Betterment."; 34 Jordan, Elizabeth The Ladies' Home Journal, 1921 Article Pro US x 26.5 cm The Ladies' Home Journal, January 1921, pgs. 29, 30; "What Do the Women Want Now," pg. Women's Suffrage 29; Penfield, E. Jean Nelson; "The Twentieth Amendment," pg. 30, Article with decorations by Penfield, E. Jean Nelson The Ladies' Home Journal, 1921 Article Pro US Nat Little; [article is continued on pg. -

Annual Report 2014

Post Office Box 7161 Winter Haven, Florida 33883-7161 863.583.7659 [email protected] www.JLGWH.com Annual Report www.facebook.com/JLGWH Instagram: JLGWH 2014 - 2015 Grow Yourself, Grow the League Grow Yourself, Grow the League BOARD MEMBERS 2014-2015 Provisionals report Jill Dunlop, President 2014-2015 Provisional Class Katie Barris, President-Elect Jennifer Schaal, Finance VP Ashley Adkinson Laura Moisa April Porter, Finance VP-Elect Courtney Boynton Marie Prisco Jill Bentley, Membership VP Stephanie Fritzgerald Natalie VanHook Adrienne Richardson, Community VP Amy Hopkins Brittany Ward Holly Hughes, Communications VP Jenni Lingenfelter Amy Miles, Public Relations Jaime Bonifay, Fund Development What an amazing group of woman we have had for a provisional class this year! Each and every provisional found a place in the League that Blair Brooks, Community Research & Project Development they truly have a passion for and gave it their all. Courtney and Hannah Taylor, Provisional Class Chair Stephanie helped with our KIK on most Wednesdays, Brittany, Jenni, Amy and Marie shined with LUTN giving many hours of service, Ashley, Laura and Natalie helped at a number of the Mobile Food MISSION Banks and even brought extra volunteers to offer a helping hand. They were all eager to help each time the League reached out for The Junior League of Greater Winter Haven, Inc. is an organization of donation requests including donating prom dress to toiletries women committed to promoting volunteerism, developing the and helping sell our wonderful cookbook “A Splash of Citrus”. potential of women and to improving the community through the effective action and leadership of trained volunteers.