Teacher's Resource Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

Background Information on Nevada Nuclear Tests

P I REVADA TEST ORMN~ATIM , 410492 Nevada Test Site # . Memury, N~*a -, . ... , ,., . .’ I ,. ..: BACKGROUND INFORMATIM . :., “ .. l“” on b NEVADA NUCLEAR TESTS ,— — — t A mmmry of previouskmlmsed information provid~ answers to questions concemtig the need for and value of nuclear tests, x8t u9e of the continental test site, on-site opem- tions and controls, public safety, and some phases of organi=tion and progti~ I BEST COPY AVAILABLE . -’0 . ..:,. \ -,. U.-;: .-j t , :. Prepared by .- OFFICE TEST INFORMATION -,-.. OF & 1235 South Xain Street “1 ;.*”*.,“’. Las Vegas, Nevada ~+;”’’j,’.:;;, Revised to July 15, 1957 .-. ,: 1“ .—7 —--— --------- ---- ;—;..,_-: ,- .— ● . , I \ f FOREWORD A large volume of official information has been is- sued concerning Nevada nuclear testing since Nevada Test Site was activated in Januw- 1951. The itio~ation tie public has been contained in official publications and reports of the Atomic Ener~ Commissim, the Department of Defense, the Federal Civil Defense Administration, other Federal organizations, and the joint Nevada Test Organization. ● Prior to the Spring 1952 series, the Test Organiza- tion received many requests from newsmen, from public officials, and from representatives of Federal agencies for a compilation of officially-approved basic inform- ationto be used M a source book. As a result the first compilation of Background Information was issued during the 1952 series. In order to meet similar requests, the information sumnary has been brought up-to-date for each subsequent Nevada Series, incorporating data released officially in the interim period. The present Background Information is such a compi- lation. It does not attempt to be all-inclusive. Many supplementary details are available elsewhere, for in- stance in the 1957 revision of *’AtomicTests in Nevada,w the various semiannual reports of the AEC to Congress, and the Government publication “The Effects of Atac Weapons.n Such publications are usually available in public libraries. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Judgment for Copyright Infringement and Permanent Injunction with the 16 Consent and on the Advice of Such Independent Legal Counsel

UMG Recordings, Inc. v. BCD Music Group, Inc. et al Doc. 199 1 JEFFREY D. GOLDMAN (SBN 155589) [email protected] 2 ROBERT J. CATALANO (SBN 240654) [email protected] 3 LOEB & LOEB LLP 10100 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 2200 4 Los Angeles, California 90067-4120 Tel: 310-282-2000/Fax: 310-282-2200 5 Attorneys for Plaintiff JS-6 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 UMG RECORDINGS, INC., a Case No. CV 07-05808 SJO (FFMx) 11 Delaware corporation Assigned to the Hon. S. James Otero 12 Plaintiff, JUDGMENT FOR COPYRIGHT 13 v. INFRINGEMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION 14 BCD MUSIC GROUP, INC., a Texas corporation; and DOES 1-10, inclusive 15 Defendants. 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 LA1837611.1 JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION 212374-10008 Dockets.Justia.com Based on the stipulation by and between plaintiff UMG Recordings, Inc., a 1 Delaware corporation (“UMG”), and BCD Music Group, Inc., a Texas corporation 2 (“BCD”), and for good cause appearing, 3 4 IT IS ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DECREED THAT: 5 6 1. BCD infringed UMG’s copyrights in the following forty-three (43) 7 sound recordings (the “43 Sound Recordings”): 8 9 1. “War with God” (Ludacris) from the album Release Therapy. 10 2. “My House” (Lloyd Banks). 3. “Over and Over” (Nelly) from the album Suit. 11 4. “3 Kings” (Slim Thug). 12 5. “Say I” (Christina Milian). 6. “Bang Bang” (Young Buck), from the album Straight Outta 13 Cashville. 14 7. “Diamonds” (Fabolous). 8. -

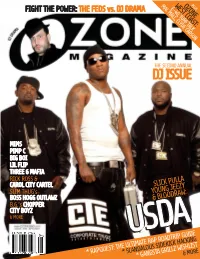

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

Native American Heritage Commission 40Th Anniversary Gala

“Itu ~(/; W/is ~the ~policy 4of ~the ~state Uwd/;that Native~ Americansll/~ remains ~ ~~~~JwJU~~JJand associated grave goods shall be repatriated.” - California Public Resources Code 5097.991 Table of Contents Event Agenda ....................................................................................................................1 Welcome Letter – Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. ...........................................................2 2016 Native American Day Proclamation ...........................................................................3 Welcome Letter – NAHC Chairperson James Ramos ...................................................... 4 Welcome Letter – NAHC Executive Secretary Cynthia Gomez .........................................5 Keynote Speaker Biography ............................................................................................6 State Capitol Rotunda Displays .......................................................................................7 Native American Heritage Commission’s Mission Statement .............................................8 Tribal People of California Map .......................................................................................13 California Indian Seal ...................................................................................................... 14 The Eighteen Unratifed Treaties of 1851-1852 between the California Indians and the United States Government .................................................................................15 NAHC Timeline -

The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY VOL. 6 NO. 2 THE GEOGRAPHY AND DIALECTS OF THE MIWOK INDIANS. BY S. A. BARRETT. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction.--...--.................-----------------------------------333 Territorial Boundaries ------------------.....--------------------------------344 Dialects ...................................... ..-352 Dialectic Relations ..........-..................................356 Lexical ...6.................. 356 Phonetic ...........3.....5....8......................... 358 Alphabet ...................................--.------------------------------------------------------359 Vocabularies ........3......6....................2..................... 362 Footnotes to Vocabularies .3.6...........................8..................... 368 INTRODUCTION. Of the many linguistic families in California most are con- fined to single areas, but the large Moquelumnan or Miwok family is one of the few exceptions, in that the people speaking its various dialects occupy three distinct areas. These three areas, while actually quite near together, are at considerable distances from one another as compared with the areas occupied by any of the other linguistic families that are separated. The northern of the three Miwok areas, which may for con- venience be called the Northern Coast or Lake area, is situated in the southern extremity of Lake county and just touches, at its northern boundary, the southernmost end of Clear lake. This 334 University of California Publications in Am. Arch. -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections.