Some Examples of Central Asian Decorative Elements in Ajanta and Bagh Indian Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Indian Painting

MODULE - V Indian Painting Painting, Performing Arts and Architecture Notes 11 INDIAN PAINTING hen you go to the market or to a museum you will find many paintings, wall hangings or work done on terracotta. Do you know that these paintings have Wtheir origin in ouir ancient past. They depict the life and customs followed by the people of those times. They also show how the kings and queens dressed or how the courtiers sat in the royal assembly. Literacy records which had a direct bearing on the art of painting show that from very early times painting both secular and religious were considered an important form of artistic expression and was practised. This need for expression is a very basic requirement for human survival and it has taken various forms since prehistoric times. Painting is one such form with which you may have been acquainted in some way or the other. Indian painting is the result of the synthesis of various traditions and its development is an ongoing process. However while adapting to new styles, Indian painting has maintained its distinct character. “Modern Indian painting in thus a reflection of the intermingling of a rich traditional inheritance with modern trends and ideas”. OBJECTIVES After reading this lesson you will be able to: trace the origin of painting from the prehistoric times; describe the development of painting during the medieval period; recognise the contribution of Mughal rulers to painting in India; trace the rise of distinct schools of painting like the Rajasthani and the Pahari schools; assess -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

The Gupta Empire: an Indian Golden Age the Gupta Empire, Which Ruled

The Gupta Empire: An Indian Golden Age The Gupta Empire, which ruled the Indian subcontinent from 320 to 550 AD, ushered in a golden age of Indian civilization. It will forever be remembered as the period during which literature, science, and the arts flourished in India as never before. Beginnings of the Guptas Since the fall of the Mauryan Empire in the second century BC, India had remained divided. For 500 years, India was a patchwork of independent kingdoms. During the late third century, the powerful Gupta family gained control of the local kingship of Magadha (modern-day eastern India and Bengal). The Gupta Empire is generally held to have begun in 320 AD, when Chandragupta I (not to be confused with Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire), the third king of the dynasty, ascended the throne. He soon began conquering neighboring regions. His son, Samudragupta (often called Samudragupta the Great) founded a new capital city, Pataliputra, and began a conquest of the entire subcontinent. Samudragupta conquered most of India, though in the more distant regions he reinstalled local kings in exchange for their loyalty. Samudragupta was also a great patron of the arts. He was a poet and a musician, and he brought great writers, philosophers, and artists to his court. Unlike the Mauryan kings after Ashoka, who were Buddhists, Samudragupta was a devoted worshipper of the Hindu gods. Nonetheless, he did not reject Buddhism, but invited Buddhists to be part of his court and allowed the religion to spread in his realm. Chandragupta II and the Flourishing of Culture Samudragupta was briefly succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta, whose reign was short. -

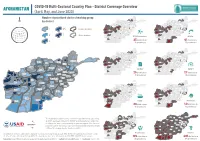

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Indian Art History from Colonial Times to the R.N

The shaping of the disciplinary practice of art Parul Pandya Dhar is Associate Professor in history in the Indian context has been a the Department of History, University of Delhi, fascinating process and brings to the fore a and specializes in the history of ancient and range of viewpoints, issues, debates, and early medieval Indian architecture and methods. Changing perspectives and sculpture. For several years prior to this, she was teaching in the Department of History of approaches in academic writings on the visual Art at the National Museum Institute, New arts of ancient and medieval India form the Delhi. focus of this collection of insightful essays. Contributors A critical introduction to the historiography of Joachim K. Bautze Indian art sets the stage for and contextualizes Seema Bawa the different scholarly contributions on the Parul Pandya Dhar circumstances, individuals, initiatives, and M.K. Dhavalikar methods that have determined the course of Christian Luczanits Indian art history from colonial times to the R.N. Misra present. The spectrum of key art historical Ratan Parimoo concerns addressed in this volume include Himanshu Prabha Ray studies in form, style, textual interpretations, Gautam Sengupta iconography, symbolism, representation, S. Settar connoisseurship, artists, patrons, gendered Mandira Sharma readings, and the inter-relationships of art Upinder Singh history with archaeology, visual archives, and Kapila Vatsyayan history. Ursula Weekes Based on the papers presented at a Seminar, Front Cover: The Ashokan pillar and lion capital “Historiography of Indian Art: Emergent during excavations at Rampurva (Courtesy: Methodological Concerns,” organized by the Archaeological Survey of India). National Museum Institute, New Delhi, this book is enriched by the contributions of some scholars Back Cover: The “stream of paradise” (Nahr-i- who have played a seminal role in establishing Behisht), Fort of Delhi. -

Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company Guest Curated by William Dalrymple

The Wallace Collection - New Exhibition Announcement: Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company Guest Curated by William Dalrymple 4 December 2019 – 19 April 2020 Tickets on sale from 16 September 2019 In partnership with DAG New Delhi-Mumbai-New York In December 2019, the Wallace Collection presents Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company. Curated by renowned writer and historian William Dalrymple, this is the first UK exhibition of works by Indian master painters commissioned by East India Company officials in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is an unprecedented opportunity to see these vivid and highly original paintings together for the first time, recognising them as among the greatest masterpieces of Indian painting. Comprising works from a wide variety of Indian traditions, the exhibition moves the emphasis from the Company commissioners onto the brilliance of the Indian creators. It belatedly honours historically overlooked artists including Shaikh Zain ud-Din, Bhawani Das, Shaikh Mohammad Amir of Karriah, Sita Ram and Ghulam Ali Khan and sheds light on a forgotten moment in Anglo-Indian history. Reflecting both the beauty of the natural world and the social reality of the time, these dazzling and often surprising artworks offer a rare glimpse of the cultural fusion between British and Indian artistic styles during this period. The exhibition highlights the conversation between traditional Indian, Islamic and Western schools and features works from Mughal, Marathi, Punjabi, Pahari, Tamil and Telugu artists. They were commissioned by a diverse cross-section of East India Company officials, ranging from botanists and surgeons, through to members of the East India Company civil service, diplomats, governors and judges, and their wives, as well as by more itinerant British artists and intellectuals passing through India for pleasure and instruction. -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Indian Folk Paintings

Exhibition: September 28, 2014 –January 11, 2015 East-West Center Gallery, Honolulu, Hawai‘i The East-West Center Arts Program presents INDIAN FOLK COLORFUL STORIES PAINTINGS Curator: Michael Schuster | Installation: Lynne Najita | Artist-in-Residence and Consultant: Gita Kar SUSHAMA CHITRAKAR NARRATES SCROLL | W. BENGAL, 2013 | PHOTO: GAYLE GOODMAN. Narrative paintings tell stories, either great epics, local regional heroes, telling painting to be exhibited include as one episode or single moment in and contemporary issues important the scrolls of the Patua from West a tale, or as a sequence of events to villagers such as HIV prevention. Bengal and the Bhopa of Rajasthan, unfolding through time. The retelling Traditionally, scroll painters and the small portable wooden of stories through narrative painting and narrative bards wandered from temples of the Khavdia Bhat, also can be seen throughout India in village to village singing their own from Rajasthan. In addition, the various forms. This exhibition focuses compositions while unwinding their exhibition will highlight narrative folk on several unique folk art forms that scroll paintings or opening their story paintings from the states of Odisha, tell the stories of deities from the boxes. Examples of this type of story - Bihar and Andhra Pradesh. Kavad Bhopa and Phad The kavad is a small mobile wooden Phad , or par , a 400-year old picture temple, made in several sizes with story-telling tradition from the desert several doors. It is constructed and state of Rajasthan, illustrates a panoply painted in the village Basi, known for of characters and scenes from medieval its wood craftsmen (called Kheradi). -

79-20 Rorient 73 Z. 1-20.Indd

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXXIII, Z. 1, 2020, (s. 119–153) DOI 10.24425/ro.2020.134049 RAJESH KUMAR SINGH (Ajanta Caves Research Programme, Dharohar, SML, Udaipur, India) ORCID: 0000-0003-4309-4943 The Earliest Two and a Half Shrine-antechambers of India Abstract The shrine antechamber is a standard component of the Indian temple architecture. It was originated in the Buddhist context, and the context was the rock-cut architecture of the Deccan and central India. The first antechamber was attempted in circa 125 CE in the Nasik Cave 17. It was patronised by Indrāgnidatta, a yavana, who possibly hailed from Bactria. The second antechamber was created in Bāgh Cave 2 in ca. late 466 CE. The patron remains unknown. The third antechamber was initiated in Ajanta Cave 16 within a few months. It was patronised by Varāhadeva, the Prime Minister of Vākāṭaka Mahārāj Hari Ṣeṇa. When the third antechamber was only half excavated, the plan was cancelled by the patron himself due to a sudden threat posed by the Alchon Hūṇs led by Mahā-Ṣāhi Khingila. The Nasik antechamber was inspired from Bactria, the Bāgh antechamber was inspired from the parrallels in the Greater Gandhāra region, whereas the Ajanta Cave 16 antechamber was inspired from Bāgh Cave 2. Keywords: Buddhist rock-cut architecture, Nasik caves, Bagh caves, Ajanta caves, shrine antechamber, central pillar, Gandhara, Alchon Hun Khingila, Vakataka Introduction This article shows how the earliest two and a half shrine-antechambers of India were developed. The shrine antechamber, as we know, is an integral part of the Indian temple architecture. -

Afghanistan: Floods

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Afghanistan: Floods DREF Operation n° MDRAF008 Glide n°: FL-2021-000050-AFG Expected timeframe: 6 months For DREF; Date of issue: 16/05/2021 Expected end date: 30/11/2021 Category allocated to the disaster or crisis: Yellow EPoA Appeal / One International Appeal Funding Requirements: - DREF allocated: CHF 497,700 Total number of people affected: 30,800 (4,400 Number of people to be 14,000 (2,000 households) assisted: households) 6 provinces (Bamyan, Provinces affected: 16 provinces1 Provinces targeted: Herat, Panjshir, Sar-i-Pul, Takhar, Wardak) Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS) has around 2,027 staff and 30,000 volunteers, 34 provincial branches and seven regional offices all over the country. There will be four regional Offices and six provincial branches involved in this operation. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: ARCS is working with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) and International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) with presence in Afghanistan. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: (i) Government ministries and agencies, Afghan National Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Committees (PDMCs), Department of Refugees and Repatriation, and Department for Rural Rehabilitation and Development. (ii) UN agencies; OCHA, UNICEF, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Organization for Migration (IOM) and World Food Programme (WFP). (iii) International NGOs: some of the international NGOs, which have been active in the affected areas are including, Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR), Danish Refugee Council (DRC), International Rescue Committee, and Care International. -

Itinerary 21 Days

THE SILK ROUTE IN CENTRAL ASIA: TAJIKISTAN Depart Sunday August 19th – September 3rd 2012 Aug.19th Sun 11.25 Depart London Heathrow on Turkish Airlines Flight 1980 via Istanbul Day 01 Aug. 20th 03.20 Arrive Dushanbe Flight TA254 Hotel Taj Palase 3* Mon : Dushanbe Half day sightseeing tour in Dushanbe including visit of famous Museum of National Antiquities, which opened in 2001. Featuring artefacts from Tajikistan's Islamic and pre- Islamic history (Greek/Bactrian, Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Hindu), the museum shows that Tajikistan was an important crossroads in Central Asia. The centrepiece is the 14m reclining Buddha in Nirvana, a 1,400 year-old statue created by the same Kushan civilisation that made the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan. Lunch at local restaurant Excursion to Hissor town (23 km from Dushanbe) to see ancient fortress of Hissor - one of the most precious historical sites of Tajikistan . Comfortably located near Dushanbe Hissor Fortress combines the traditional elements of power, trade and culture of the ancient Tajik nation. Visit Medrassah Kuhna (16th c) and Museum of Tajik Way of life there, 19c Medrassah nearby and mausoleum of Sufi saint Mahdumi Azam. Later visit picturesque Varzob gorge and enjoy short rest by the mountain river side. Varzob Gorge is a beautiful alpine mountain region within easy driving distance of Dushanbe. The main road north out of Dushanbe follows the route of the rushing Varzob River for about 70 Km, before climbing steeply to Anzob Pass (3,373 m). There are also natural thermal springs at Khoja Obi Garm. Varzob is perfect for walking, rock climbing or just a quiet picnic. -

AFGHANISTAN MAP Central Region

Chal #S Aliabad #S BALKH Char Kent Hazrat- e Sultan #S AFGHANISTAN MAP #S Qazi Boi Qala #S Ishkamesh #S Baba Ewaz #S Central Region #S Aibak Sar -e Pul Islam Qala Y# Bur ka #S #S #S Y# Keshendeh ( Aq Kopruk) Baghlan-e Jadeed #S Bashi Qala Du Abi #S Darzab #S #S Dehi Pul-e Khumri Afghan Kot # #S Dahana- e Ghori #S HIC/ProMIS Y#S Tukzar #S wana Khana #S #S SAMANGAN Maimana Pasni BAGHLAN Sar chakan #S #S FARYAB Banu Doshi Khinjan #S LEGEND SARI PUL Ruy-e Du Ab Northern R#S egion#S Tarkhoj #S #S Zenya BOUNDARIES Qala Bazare Tala #S #S #S International Kiraman Du Ab Mikh Zar in Rokha #S #S Province #S Paja Saighan #S #S Ezat Khel Sufla Haji Khel District Eshqabad #S #S Qaq Shal #S Siyagerd #S UN Regions Bagram Nijrab Saqa #S Y# Y# Mahmud-e Raqi Bamyan #S #S #S Shibar Alasai Tagab PASaRlahWzada AN CharikarQara Bagh Mullah Mohd Khel #S #S Istalif CENTERS #S #S #S #S #S Y# Kalakan %[ Capital Yakawlang #S KAPISA #S #S Shakar Dara Mir Bacha Kot #S Y# Province Sor ubi Par k- e Jamhuriat Tara Khel BAMYAN #S #S Kabul#S #S Lal o Sar Jangal Zar Kharid M District Tajikha Deh Qazi Hussain Khel Y# #S #S Kota-e Ashro %[ Central Region #S #S #S KABUL #S ROADS Khord Kabul Panjab Khan-e Ezat Behsud Y# #S #S Chaghcharan #S Maidan Shar #S All weather Primary #S Ragha Qala- e Naim WARDAK #S Waras Miran Muhammad Agha All weather Secondary #S #S #S Azro LOGAR #S Track East Chake-e Wnar dtark al RegiKolangar GHOR #S #S RIVERS Khoshi Sayyidabad Bar aki Bar ak #S # #S Ali Khel Khadir #S Y Du Abi Main #S #S Gh #S Pul-e Alam Western Region Kalan Deh Qala- e Amr uddin