The Sacred Tree of the Ancient Maya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

On the Present-Day Veneration of Sacred Trees in the Holy Land

ON THE PRESENT-DAY VENERATION OF SACRED TREES IN THE HOLY LAND Amots Dafni Abstract: This article surveys the current pervasiveness of the phenomenon of sacred trees in the Holy Land, with special reference to the official attitudes of local religious leaders and the attitudes of Muslims in comparison with the Druze as well as in monotheism vs. polytheism. Field data regarding the rea- sons for the sanctification of trees and the common beliefs and rituals related to them are described, comparing the form which the phenomenon takes among different ethnic groups. In addition, I discuss the temporal and spatial changes in the magnitude of tree worship in Northern Israel, its syncretic aspects, and its future. Key words: Holy land, sacred tree, tree veneration INTRODUCTION Trees have always been regarded as the first temples of the gods, and sacred groves as their first place of worship and both were held in utmost reverence in the past (Pliny 1945: 12.2.3; Quantz 1898: 471; Porteous 1928: 190). Thus, it is not surprising that individual as well as groups of sacred trees have been a characteristic of almost every culture and religion that has existed in places where trees can grow (Philpot 1897: 4; Quantz 1898: 467; Chandran & Hughes 1997: 414). It is not uncommon to find traces of tree worship in the Middle East, as well. However, as William Robertson-Smith (1889: 187) noted, “there is no reason to think that any of the great Semitic cults developed out of tree worship”. It has already been recognized that trees are not worshipped for them- selves but for what is revealed through them, for what they imply and signify (Eliade 1958: 268; Zahan 1979: 28), and, especially, for various powers attrib- uted to them (Millar et al. -

Metaphors of Relative Elevation, Position and Ranking in Popol Vuh

METAPHORS OF RELATIVE ELEVATION, POSITION AND RANKING IN POPOL VUH Nathaniel TARN and Martin PRECHTEL Rutgers University This paper is an account of work very much in progress on the textual analysis of Popol V uh, and is one study among others (since this theme is attracting a number of students today) of inter-con nections and mutual illuminations between Popol Vuh and the con temporary ethnographic record in Highland Guatemala and Chiapas. For some considerable time now Popol Vuh has been considered as the major extant text of the Mesoamerican literary traditions, and as one of the most remarkable of all human creation stories, both for its beauty and for the complexity of its cosmological and mythical messages. While it may or may not have had a hieroglyphic original, the present alphabetic version of Po pol V uh wars written down some where between 1545 and 1558 by an anonymous member of the Cavek lineage of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. This lineage had been a ruling house until it fell to the Spaniards in 1524. The manu script was copied by Francisco de Ximenez, a Spanish priest, some 150 years later. While there are references to Christianity in the text, these are few and it is generally regarded as one of the purest extant accounts of prehispanic Maya world-view. At the end of the hook, what we call mythical history shades into the historical history of the Quiche, so that the hook can serve as an illustration of the extent to which these two kinds of history are not held a,part by Maya generally. -

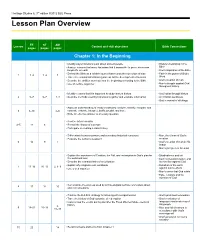

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

Introducing Izapa

Ancient Mesoamerica, 29 (2018), 255–264 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2018 doi:10.1017/S0956536118000494 INTRODUCING IZAPA Robert M. Rosenswiga and Julia Guernseyb aDepartment of Anthropology, State University of New York at Albany, Albany, New York 12222 bDepartment of Art and Art History, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78705 Abstract This paper introduces the articles that comprise this Special Issue on Izapa. First, we review early reporting and assessments of Izapa’s monuments as well as archaeological investigations undertaken at the site during the twentieth century. Next, we describe more recent developments in interpretation and new archeological excavations and survey data collected during the past two decades. The papers in this Special Issue present new information that contribute to our evolving understanding of Izapa during the millennium that stretches from the Middle Formative period through the Middle Classic period (700 b.c.–a.d. 600). They serve as a status report on our understanding of the still largely enigmatic ancient kingdom, its regional structure, and connections to contemporaneous Isthmian sites. INTRODUCTION Blanca collapsed after a few centuries, and population declined in the immediate region. Its demise was a continuation of a millennium Izapa followed a trajectory of settled life that began at the beginning of political volatility characterized by a succession of polities coa- of the second millennium b.c. in the Soconusco region of Chiapas lescing and collapsing on the coastal plain (Love 2002b, 2007, and neighboring Guatemala (Figure 1). A series of Early Formative 2011). This rise-and-fall sequence provided the context in which (1900–1000 b.c., all dates calibrated) centers characterize the mounded architecture was adopted at Izapa sometime around 800 Mazatán zone of the Soconusco region (Clark and Pye 2000; b.c. -

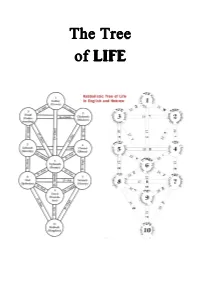

The Hexagonal Geometry of the Tree of Life July 5, 2008

The Hexagonal Geometry of the Tree of Life July 5, 2008 The Hexagonal Geometry Of the Tree of Life By Patrick Mulcahy This short treatise explores (using polyhex mathematics) the special relationship that exists between the kabbalistic Tree of Life diagram and the geometry of the simple hexagon. It reveals how the ten sefirot and the twenty- two pathways of the Tree of Life are each individually and uniquely linked to the hexagonal form. The Hebrew alphabet is also shown to be esoterically associated with the geometry of the hexagon. This treatise is intended to be a primer for the further study and esoteric application of polyhex mathematics. First Edition (Expanded) Copyright 2008 © Patrick Mulcahy AstroQab Publishing 2008 Email: [email protected] Website: http://members.optusnet.com.au/~astroqab 2 The Hexagonal Geometry of the Tree of Life July 5, 2008 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................. 6 General Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Introduction to the Polyhex Tree of Life ................................................................................ 9 The Polyhex Tree of Life ...................................................................................................... 13 The Three Highest Sefirot ................................................................................................ 13 The Seven Lower -

The Toltec Invasion and Chichen Itza

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: Breaking the Maya Code Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs Angkor and the Khmer Civilization India: A Short History The Incas The Aztecs See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com 7 THE POSTCLASSIC By the close of the tenth century AD the destiny of the once proud and independent Maya had, at least in northern Yucatan, fallen into the hands of grim warriors from the highlands of central Mexico, where a new order of men had replaced the supposedly more intellectual rulers of Classic times. We know a good deal about the events that led to the conquest of Yucatan by these foreigners, and the subsequent replacement of their state by a resurgent but already decadent Maya culture, for we have entered into a kind of history, albeit far more shaky than that which was recorded on the monuments of the Classic Period. The traditional annals of the peoples of Yucatan, and also of the Guatemalan highlanders, transcribed into Spanish letters early in Colonial times, apparently reach back as far as the beginning of the Postclassic era and are very important sources. But such annals should be used with much caution, whether they come to us from Bishop Landa himself, from statements made by the native nobility, or from native lawsuits and land claims. These are often confused and often self-contradictory, not least because native lineages seem to have deliberately falsified their own histories for political reasons. Our richest (and most treacherous) sources are the K’atun Prophecies of Yucatan, contained in the “Books of Chilam Balam,” which derive their name from a Maya savant said to have predicted the arrival of the Spaniards from the east. -

The Rulers of Palenque a Beginner’S Guide

The Rulers of Palenque A Beginner’s Guide By Joel Skidmore With illustrations by Merle Greene Robertson Citation: 2008 The Rulers of Palenque: A Beginner’s Guide. Third edition. Mesoweb: www. mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/PalenqueRulers-03.pdf. Publication history: The first edition of this work, in html format, was published in 2000. The second was published in 2007, when the revised edition of Martin and Grube’s Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens was still in press, and this third conforms to the final publica- tion (Martin and Grube 2008). To check for a more recent edition, see: www.mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/rulers.html. Copyright notice: All drawings by Merle Greene Robertson unless otherwise noted. Mesoweb Publications The Rulers of Palenque INTRODUCTION The unsung pioneer in the study of Palenque’s dynastic history is Heinrich Berlin, who in three seminal studies (Berlin 1959, 1965, 1968) provided the essential outline of the dynasty and explicitly identified the name glyphs and likely accession dates of the major Early and Late Classic rulers (Stuart 2005:148-149). More prominent and well deserved credit has gone to Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1974), who summarized the rulers of Palenque’s Late Classic and gave them working names in Ch’ol Mayan (Stuart 2005:149). The present work is partly based on the transcript by Phil Wanyerka of a hieroglyphic workshop presented by Schele and Mathews at the 1993 Maya Meet- ings at Texas (Schele and Mathews 1993). Essential recourse has also been made to the insights and decipherments of David Stuart, who made his first Palenque Round Table presentation in 1978 at the age of twelve (Stuart 1979) and has recently advanced our understanding of Palenque and its rulers immeasurably (Stuart 2005). -

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

Silk Cotton Vs. Bombax Vs. Banyan

Ceiba pentandra Kopok tree, Silk-cotton tree Ta Prohm, Cambodia By Isabel Zucker Largest known specimen in Lal Bagh Gardens in Bangalore, India. http://scienceray.com/biology/botany/amazing-trees-from-around-the-world-the-seven-wonder-trees/ Ceiba pentandra Taxonomy • Family: Malvaceae • Sub family: Bombacaceae -Bombax spp. in same family - much online confusion as to which tree is primarily in Ta Praham, Cambodia. • Fig(Moraceae), banyan and kapok trees in Ta Praham • Often referred to as a banyan tree, which is quite confusing. Distribution • Originated in the American tropics, natural and human distribution. • Africa, Asia. – Especially Indonesia and Thailand • Indian ocean islands • Ornamental shade tree • Zone – Humid areas, rainforest, dry areas – Mean annual precipitation 60-224 inches per year – Temperatures ranging from 73-80 unaffected by frost – Elevation from 0-4,500 feet – Dry season ranging from 0-6 months Characteristics • Rapidly growing, deciduous • Reaches height up to 200 feet • Can grow 13 feet per year • Diameter up to 9 feet above buttress – Buttress can extend 10 feet from the trunk and be 10 feet tall • large umbrella-shaped canopies emerge above the forest canopy • http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/caribarch/ceiba.htm • Home to many animals – Birds, frogs, insects – Flowers open in the evening, pollinated by bats • Epiphytes grow in branches • Compound leaves with 5-8 lance- shaped leaflets 3-8 inches long • Dense clusters of whitish to pink flowers December to February – 3-6 inch long, elliptical fruits. – Seeds of fruit surrounded by dense, cottony fibers. – Fibers almost pure cellulose, buoyant, impervious to water, low thermal conductivity, cannot be spun.