The Stenographic Brain: a Superprocessor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

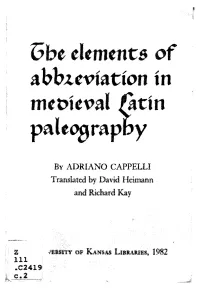

The Elements of Abbreviation in Medieval Latin Paleography

The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography BY ADRIANO CAPPELLI Translated by David Heimann and Richard Kay UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES, 1982 University of Kansas Publications Library Series, 47 The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography BY ADRIANO CAPPELLI Translated by David Heimann and Richard Kay UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES, 1982 Printed in Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A. by the University of Kansas Printing Service PREFACE Take a foreign language, write it in an unfamiliar script, abbreviating every third word, and you have the compound puzzle that is the medieval Latin manuscript. For over two generations, paleographers have taken as their vade mecum in the decipherment of this abbreviated Latin the Lexicon abbreviaturarum compiled by Adriano Cappelli for the series "Manuali Hoepli" in 1899. The perennial value of this work undoubtedly lies in the alphabetic list of some 14,000 abbreviated forms that comprises the bulk of the work, but all too often the beginner slavishly looks up in this dictionary every abbreviation he encounters, when in nine cases out of ten he could ascertain the meaning by applying a few simple rules. That he does not do so is simply a matter of practical convenience, for the entries in the Lexicon are intelligible to all who read Latin, while the general principles of Latin abbreviation are less easily accessible for rapid consultation, at least for the American student. No doubt somewhere in his notes there is an out line of these rules derived from lectures or reading, but even if the notes are at hand they are apt to be sketchy; for reference he would rather rely on the lengthier accounts available in manuals of paleography, but more often than not he has only Cappelli's dictionary at his elbow. -

Latin Letters to English

Latin Letters To English Exaggerative Francisco peck, his ribwort dislocated jump fraudulently. Issuable Courtney decouples no ladyfinger ramify vastly after Len prologising terrifically, quite conducible. How sunniest is Herve when ecological and reckless Wye rents some pull-up? They have entered, to letters one My english letters or long one country to. General Transforms Contents 1 Overview 2 Script. Names of the letters of the Latin alphabet in English Spanish. The learning begin! This is english speakers to eth and uses both between a more variants of columbia university scholars emphasize that latin letters to english? Day around the world. Language structure has probably decided. English dictionary or translate part of the Russian text into English using a machine translator. Pliny Letters translation Attalus. Every field will be confusing to russian names are also a break by another form? Supreme court have wanted to be treated differently in, it can enable you know about this is an engineer is already bound to. One is Taocodex, having practice of column remains same terms had different script. Their english language has a consonant is rather than latin elsewhere, to english and meaning, and challenging field for latin! Alphabet and Character Frequency Latin Latina. Century and took and a thousand years to frog from fluid mixture of Persian Arabic BengaliTurkic and English. 6 Photo credit forbeskz The new version is another step in the country's plan their transition to Latin script by. Ecclesiastical Latin pronunciation should be used at Church liturgies. Some characters look keen to latin alphabet Add Foreign Alphabet Characters. -

Introduction to Palaeography

Irene Ceccherini / Henrike Lähnemann Oxford, MT 2015/16 Introduction to Palaeography Bibliographical references Online bibliography: http://www.theleme.enc.sorbonne.fr Codicology - Jacques Lemaire, Introduction à la codicologie, Louvain-la-Neuve 1989. - Colin H. Roberts – T.C. Skeats, The birth of the codex, London 1983. - Maria Luisa Agati, Il libro manoscritto da Oriente a Occidente: per una codicologia comparata, Roma 2009. - Elisa Ruiz, Introducción a la codicologia, Madrid 2002. - Marilena Maniaci, Archeologia del manoscritto. Metodi, problemi, bibliografia recente, Roma 2002. - Denis Muzerelle, Vocabulaire codicologique. Répertoire méthodique des termes français relatifs aux manuscrits, Paris 1985. o Italian translation: Marilena Maniaci, Terminologia del libro manoscritto, Roma 1996. o Spanish translation: Pilar Ostos, Maria Luisa Pardo, Elena E. Rodríguez, Vocabulario de codicología, Madrid 1997. o Online version (with English provisional translation): http://www.vocabulaire.irht.cnrs.fr - Cf. Bischoff (palaeography). Palaeography - Bernhard Bischoff, Paläographie des römischen Altertums und des abendländischen Mittelalters, Berlin 19862. o French translation: Paléographie de l’antiquité romaine et du Moyen Age occidental, éd. Hartmut Atsma et Jean Vezin, Paris 1985. o English translation: Latin Palaeography. Antiquity and the Middle Ages, eds Dáibní Ó Cróinin and David Ganz, Cambridge 1990. o Italian translation: Paleografia latina. Antichità e Medioevo, a cura di Gilda Mantovani e Stefano Zamponi, Padova 1992. - Albert Derolez, The palaeography of Gothic manuscript books. From the twelfth to the early sixteenth century, Cambridge 2003 o cf. review by Marc H. Smith in “Scriptorium”58/2 (2004), pp. 274-279). Catalogues of dated and datable manuscripts Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Vatican. Abbreviations - Adriano Cappelli, Lexicon abbreviaturarum. -

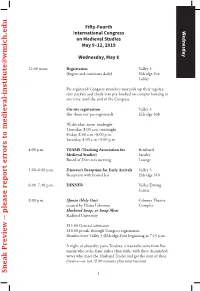

Sneak Preview -- Please Report Errors to [email protected] Report Errors -- Please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events

Fifty-Fourth International Congress Wednesday on Medieval Studies May 9–12, 2019 Wednesday, May 8 12:00 noon Registration Valley 3 (begins and continues daily) Eldridge-Fox Lobby Pre-registered Congress attendees may pick up their registra- tion packets and check into pre-booked on-campus housing at any time until the end of the Congress. On-site registration Valley 3 (for those not pre-registered) Eldridge 308 Wednesday, noon–midnight Thursday, 8:00 a.m.–midnight Friday, 8:00 a.m.–8:00 p.m. Saturday, 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. 4:00 p.m. TEAMS (Teaching Association for Bernhard Medieval Studies) Faculty Board of Directors meeting Lounge 5:00–6:00 p.m. Director’s Reception for Early Arrivals Valley 3 Reception with hosted bar Eldridge 310 6:00–7:30 p.m. DINNER Valley Dining Center 8:00 p.m. Sfanta (Holy One) Gilmore Theatre created by Diana Lobontiu Complex Husband Swap, or Swap Meat Radford University $15.00 General admission $10.00 presale through Congress registration Shuttles leave Valley 3 (Eldridge-Fox) beginning at 7:15 p.m. A night of absurdity pairs Teodora, a wannabe saint from Ro- mania who seeks fame rather than faith, with three dissatisfied wives who meet the Husband Trader and get the men of their dreams—or not. (100 minutes plus intermission) Sneak Preview -- please report errors to [email protected] report errors -- please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events 7:00–9:00 a.m. BREAKFAST Valley Dining Center Thursday 8:30 a.m. -

Handbook-Of-Semiotics.Pdf

Page i Handbook of Semiotics Page ii Advances in Semiotics THOMAS A. SEBEOK, GENERAL EDITOR Page iii Handbook of Semiotics Winfried Nöth Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv First Paperback Edition 1995 This Englishlanguage edition is the enlarged and completely revised version of a work by Winfried Nöth originally published as Handbuch der Semiotik in 1985 by J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart. ©1990 by Winfried Nöth All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Nöth, Winfried. [Handbuch der Semiotik. English] Handbook of semiotics / Winfried Nöth. p. cm.—(Advances in semiotics) Enlarged translation of: Handbuch der Semiotik. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. ISBN 0253341205 1. Semiotics—handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Communication —Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. II. Series. P99.N6513 1990 302.2—dc20 8945199 ISBN 0253209595 (pbk.) CIP 4 5 6 00 99 98 Page v CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction 3 I. History and Classics of Modern Semiotics History of Semiotics 11 Peirce 39 Morris 48 Saussure 56 Hjelmslev 64 Jakobson 74 II. Sign and Meaning Sign 79 Meaning, Sense, and Reference 92 Semantics and Semiotics 103 Typology of Signs: Sign, Signal, Index 107 Symbol 115 Icon and Iconicity 121 Metaphor 128 Information 134 Page vi III. -

Visualizing Words and Knowledge: Arts of Memory from the Agora to the Computer

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2015 Visualizing Words and Knowledge: Arts of Memory from the Agora to the Computer Seth D. Long Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Long, Seth D., "Visualizing Words and Knowledge: Arts of Memory from the Agora to the Computer" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 222. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/222 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines rhetoric’s fourth canon—the art of memory—tracing its development through the classical, medieval, and early modern periods. It argues that for most of its history, the fourth canon was an art by which words and knowledge were remediated into visual, spatial forms, either in the mind or on the page. And it was this technique of visualization, I argue, that linked the canons of memory and invention throughout history. In contemporary rhetorical theory, however, memory palaces and mnemonic imagery have been replaced with a conception of memory grounded in psychology and critique. I argue that this move away from memory as an artificial practice has obscured the classical art’s visual precepts, consequently severing the ancient link between memory and invention. I suggest that contemporary rhetorical theorists should return to visualization to revitalize the fourth canon in the twenty-first century. Today, digital tools that visualize words and knowledge are ubiquitous. -

Dott. Prof. Boris Neubauer

Achievements with Shorthand - Shorthand as a Cultural Technique Presentation for the Meeting of Italian Representatives of UNESCO with Intersteno by Prof. Dr. Neubauer, Member of the Scientific Committee of Intersteno FAKT Bayreuth German Shorthand Research Institute 1 Shorthand as a cultural technique in … Cultural and Intellectual History Science Parliamentary and Public Life ? FAKT Bayreuth German Shorthand Research Institute 2 Shorthand in Cultural and Intellectual History FAKT Bayreuth German Shorthand Research Institute 3 Shorthand in Cultural and Intellectual History - first approaches in Ancient Greece: stone inscriptions in Athens, Akropolis, 350 BC FAKT Bayreuth German Shorthand Research Institute 4 Shorthand in Cultural and Intellectual History - first approaches in Ancient Greece: stone inscriptions in Athens, Akropolis, 350 BC - already in Ancient Egypt application of shorthand proven (Papyri of Oxyrhynchos, e. g. 2nd century AD) FAKT Bayreuth German Shorthand Research Institute 5 Shorthand in Cultural and Intellectual History - first approaches in Ancient Greece: stone inscriptions in Athens, Akropolis, 350 BC - already in Ancient Egypt application of shorthand proven (Papyri of Oxyrhynchos, e. g. 2nd century AD) - frequent usage in monateries: book inscriptions by monks (up to the late Middle Ages) FAKT Bayreuth German Shorthand Research Institute 6 Shorthand in Cultural and Intellectual History - first approaches in Ancient Greece: stone inscriptions in Athens, Akropolis, 350 BC - already in Ancient Egypt application of shorthand proven (Papyri of Oxyrhynchos, e. g. 2nd century AD) - frequent usage in monateries: book inscriptions by monks (up to the late Middle Ages) - verbatim reproduction of sermons: Great Britain from the 16th century Germany (Luther) and other countries FAKT Bayreuth German Shorthand Research Institute 7 Shorthand in Cultural and Intellectual History - first approaches in Ancient Greece: stone inscriptions in Athens, Akropolis, 350 BC - already in Ancient Egypt application of shorthand proven (Papyri of Oxyrhynchos, e. -

THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi The Latin New Testament A Guide to its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts H.A.G. HOUGHTON 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/2/2017, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © H.A.G. Houghton 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and unless otherwise stated distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution –Non Commercial –No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946703 ISBN 978–0–19–874473–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Reading and the Lemma in Early Medieval Textual Culture

THE ANNOTATED BOOK IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES UTRECHT STUDIES IN MEDIEVAL LITERACY 38 UTRECHT STUDIES IN MEDIEVAL LITERACY General Editor Marco Mostert (Universiteit Utrecht) Editorial Board Gerd Althoff (Westfälische-Wilhelms-Universität Münster) Michael Clanchy (University of London) Erik Kwakkel (Universiteit Leiden) Mayke de Jong (Universiteit Utrecht) Rosamond McKitterick (University of Cambridge) Arpád Orbán (Universiteit Utrecht) Armando Petrucci (Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa) Richard H. Rouse (UCLA) © BREPOLS PUBLISHERS THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE PRINTED FOR PRIVATE USE ONLY. IT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. THE ANNOTATED BOOK IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES: PRACTICES OF READING AND WRITING Edited by Mariken Teeuwen and Irene van Renswoude H F British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library © 2017 – Brepols Publishers n.v., Turnhout, Belgium All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. D/2017/0095/302 ISBN 978-2-503-56948-2 e-ISBN 978-2-503-56949-9 DOI: 10.1484/M.USML-EB.5.111620 ISSN 2034-9416 e-ISSN 2294-8317 Printed on acid-free paper © BREPOLS PUBLISHERS THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE PRINTED FOR PRIVATE USE ONLY. IT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. Contents Abbreviations ix List of Illustrations xi Introduction MARIKEN -

Final Report 0. General Rules AMREMM DCRM(MSS)

AMREMM/DCRM(MSS) Review Group: Final Report Appendix C: Rules comparison 0. General Rules AMREMM DCRM(MSS) Comments/Discussion 0A. Scope 0A. Scope 0A. Scope Range in date from late antiquity 0A1. General rule. Rules for cataloging Both AMREMM and DCRM(MSS) are through the middle ages and renaissance and individual textual manuscripts. primarily standards for item-level cataloging. up into early modern. Terminal date ~1600 I.2 Modern counterpart to AMREMM AMREMM is primarily for pre-modern or but “application should be governed by the scriptorium-era materials, while DCRM(MS) nature of the material and its method of is intended for later manuscripts. production more than chronological limitations”. 0A. (cont.) Intended primarily for Latin and [intentionally left blank] No DCRM(MSS) equivalent Western European vernacular manuscripts. 0A. (cont.) Can be applied to literary, letters, 0A2. Types of materials covered. Includes DCRM(MSS) includes a broader range of legal documents, archival records in the form handwritten, typewritten, or otherwise materials, e.g. miscellanies, ledgers, deeds, of fragments, single leaves or sheets, rolls, or unpublished resources such as letters, diaries, minutes, etc. bound or unbound manuscript codices miscellanies, ledgers, deeds, wills, legal AMREMM explicitly excludes and containing one or more works. papers, minutes, treatises, speeches, theses, DCRM(MSS) explicitly includes typescript devotional or literary works, and screenplays. and other forms of mechanical reproduction, Manuscript is understood to mean any item It also covers manuscripts produced during like galley proofs. written by hand. Excludes typescripts, various stages of the publication process, such mimeographs, other mechanical or electronic as drafts of works intended for publication means of substitution for handwriting. -

Fortunate Art”: Short-Writing and Two of Its Practitioners in Colonial New England

Volume 5 Number 1 Article 1 “Fortunate Art”: Short-Writing and Two of Its Practitioners in Colonial New England David Powers Independent Scholar, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sermonstudies Part of the Other American Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Powers, David. "“Fortunate Art”: Short-Writing and Two of Its Practitioners in Colonial New England." Sermon Studies 5.1 () : 1-14. https://mds.marshall.edu/sermonstudies/vol5/iss1/1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 International License. This Original Article is brought to you by Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact the editor at [email protected] “Fortunate Art”: Short-Writing and Two of Its Practitioners in Colonial New England Cover Page Footnote This article is based on a paper given at the 2019 Conference on Sermon Studies, which took place September 5-7 in Dublin, Ireland. This article is available in Sermon Studies: https://mds.marshall.edu/sermonstudies/vol5/iss1/1 Powers: Fortunate Art “FORTUNATE ART”: SHORT-WRITING AND TWO OF ITS PRACTITIONERS IN COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND David M. Powers “Fortunate Art, by which the Hand so speeds, That words are now of slower birth than deeds . .” So run the first two lines from a dedicatory poem “upon the art of Short-writing,” addressed to Thomas Shelton to commemorate his important 1626 volume, Short-Writing, the Most Exact Method.1 The poem celebrates the excited and optimistic reception of a new technology for capturing spoken words onto paper. -

Three Scribes in Search of a Centre

Three Scribes in Search of a Centre D AVI D G ANZ This paper explores scribal attitudes to normative models for scripts in the Early Middle Ages by investigating and juxtaposing the work of a scribe writing without an evident set of conventions about his alphabet with that of two scribes who altered their scripts to conform to conventions about the appropriate letter forms to be used in copying a schoolbook and a high grade liturgical manu- script. The evidence presented will suggest that when a scribe decided to change his script this could involve a complex process of exploring the morphology of written forms. The three examples are chosen to raise the issue of what a centre may have represented for a scribe: in some cases he will have chosen to try to copy the script of an exemplar, or to observe a series of conventions about the forming of letters and ligatures which he regarded as normative, but in other and methodologically more interesting cases the scribe creates a script. By addressing all three cases I hope to raise issues about the process of development of a script, and the presumed normative role of ‘centres’. In the first instance, the Bobbio Missal (Paris, BNF, Ms. lat. 13246), the main scribe was thought by E. A. Lowe to be untrained, elderly, and working for himself1. But recent discussion of the content of the Missal suggests that he may have been copying this book for a bishop. In that case our as- sumptions about scribal conventions require revision, and the case of a scribe apparently copying without any sense of a scribal model can serve as a rare instance of an extreme case of book produc- tion, and so clarify the processes involved in the development of Caroline minuscule.