2015 Edition of Jabberwocky (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

Audition Pack

AUDITION PACK Production details Our production of Alice in Wonderland will take place at Millers Theatre, Seefeldstrasse 225, 8008 Zürich. Production dates Saturday 2nd March 2019 at 2.30pm and 6.30pm Sunday 3rd March 2019 at 2.30pm and 6.30pm Want to audition? If you are aged between 8 and 18 you can book your audition time by signing up at www.simplytheatre.com/productions/audition Audition details Auditions for Alice in Wonderland will take place on the 8th and 9th December 2018 at Gymnos Studios, Gladbachstr. 119, 8044 Zürich. If you are selected for a CALLBACK, you will need to be available on the afternoon of Sunday 9th December. If you want to audition but cannot make these dates please let us know in advance and we may be able to help. Audition times are: Saturday 8th December Sunday 9th December Session 1: 14.45 – 15.45 Session 4: 11.00 – 12.00 Session 2: 15.55 – 16.55 Session 3: 17.00 – 18.00 Recall auditions: 13.00 – 16.00 (by invite only) Please indicate which audition slot you would like when booking your time. 1 What will I be doing in the audition process? As part of your audition, you will be asked to perform a small monologue. These monologues are listed at the end of this pack. This monologue should be memorised. When learning your monologue, remember to consider where you think your character is at the time of this monologue, who (s)he may be talking to, and what they are feeling. How can you get this information over to your audience (audition panel) through your audition? You may feel free to choose any of the monologues for your audition, as no matter what you perform at audition you will still be considered for all parts. -

Table of Contents

On s V·v" tage Artlerican The lth I r- B ater A _.. tP lac!( J ~~ls For Yoll 0llrney d table of Contents: Letter from the Producer ..... ......................................................... 3 Before You Go .......................................................................4 Theater Etiquette ....................................................................... 5 Scenic Breakdown .......................................................................6 Synopsis ................................................................................ ? Touchstones ........................................................................... 8 & 9 After the Show 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 •• 0 000 0 0 00 0 000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 000 0 •• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 •••• 00 •• 10 Interdisciplinary Activities ............................................ ......... 11 & 12 Acrostic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ••• 00 0 0 0 0 0 00 0 00 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.13 Think Theatrically ..................................................................... 14 Fan Letter 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00 00 0 •• 0 00 0 ••• 0 0 00 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 •• 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.15 Theater Vocabulary ..................................................................... 16 Write a Review ..................... ................................................ 17 Careers in the Arts ..................................................................... 18 African Americans in the Performing Arts .................................... 19 & 20 Draw a Picture ............ .................................................................. 21 Crossword ....................................................................................22 Supplemental Reading ..................................................... -

Beets Documentation Release 1.5.1

beets Documentation Release 1.5.1 Adrian Sampson Oct 01, 2021 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Guides..................................................3 1.2 Reference................................................. 14 1.3 Plugins.................................................. 44 1.4 FAQ.................................................... 120 1.5 Contributing............................................... 125 1.6 For Developers.............................................. 130 1.7 Changelog................................................ 145 Index 213 i ii beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 Welcome to the documentation for beets, the media library management system for obsessive music geeks. If you’re new to beets, begin with the Getting Started guide. That guide walks you through installing beets, setting it up how you like it, and starting to build your music library. Then you can get a more detailed look at beets’ features in the Command-Line Interface and Configuration references. You might also be interested in exploring the plugins. If you still need help, your can drop by the #beets IRC channel on Libera.Chat, drop by the discussion board, send email to the mailing list, or file a bug in the issue tracker. Please let us know where you think this documentation can be improved. Contents 1 beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Guides This section contains a couple of walkthroughs that will help you get familiar with beets. If you’re new to beets, you’ll want to begin with the Getting Started guide. 1.1.1 Getting Started Welcome to beets! This guide will help you begin using it to make your music collection better. Installing You will need Python. Beets works on Python 3.6 or later. • macOS 11 (Big Sur) includes Python 3.8 out of the box. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

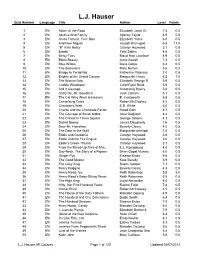

AR Quizzes for L.J. Hauser

L.J. Hauser Quiz Number Language Title Author Level Points 1 EN Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet Gr 7.4 0.5 2 EN All-of-a-Kind Family Sydney Taylor 4.9 0.5 3 EN Amos Fortune, Free Man Elizabeth Yates 6.0 0.5 4 EN And Now Miguel Joseph Krumgold 6.8 11.0 5 EN "B" is for Betsy Carolyn Haywood 3.1 0.5 6 EN Bambi Felix Salten 4.6 0.5 7 EN Betsy-Tacy Maud Hart Lovelace 4.9 0.5 8 EN Black Beauty Anna Sewell 7.3 0.5 9 EN Blue Willow Doris Gates 6.4 0.5 10 EN The Borrowers Mary Norton 5.6 0.5 11 EN Bridge to Terabithia Katherine Paterson 7.0 0.5 12 EN Brighty of the Grand Canyon Marguerite Henry 6.2 7.0 13 EN The Bronze Bow Elizabeth George S 5.9 0.5 14 EN Caddie Woodlawn Carol Ryrie Brink 5.6 0.5 15 EN Call It Courage Armstrong Sperry 5.0 0.5 16 EN Carry On, Mr. Bowditch Jean Latham 5.1 0.5 17 EN The Cat Who Went to Heaven E. Coatsworth 5.8 0.5 18 EN Centerburg Tales Robert McCloskey 5.2 0.5 19 EN Charlotte's Web E.B. White 6.0 0.5 20 EN Charlie and the Chocolate Factor Roald Dahl 6.7 0.5 21 EN The Courage of Sarah Noble Alice Dalgliesh 4.2 0.5 22 EN The Cricket in Times Square George Selden 4.3 0.5 23 EN Daniel Boone James Daugherty 7.6 0.5 24 EN Dear Mr. -

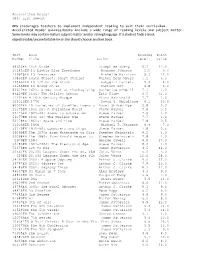

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Lewis Carroll 'The Jabberwocky'

Lewis Carroll ‘The Jabberwocky’ 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. "Beware the Jabberwock, my son The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun The frumious Bandersnatch!" He took his vorpal sword in hand; Long time the manxome foe he sought— So rested he by the Tumtum tree, And stood awhile in thought. And, as in uffish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, And burbled as it came! One, two! One, two! And through and through The vorpal blade went snicker-snack! He left it dead, and with its head He went galumphing back. "And hast thou slain the Jabberwock? Come to my arms, my beamish boy! O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!" He chortled in his joy. 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. Rudyard Kipling ‘The Way Through The Woods’ They shut the road through the woods Seventy years ago. W eather and rain have undone it again, And now you would never know There was once a road through the woods Before they planted the trees. It is underneath the coppice and heath And the thin anemones. Only the keeper sees That, where the ring-dove broods, And the badgers roll at ease, There was once a road through the woods. Yet, if you enter the woods Of a summer evening late, When the night-air cools on the trout-ringed pools Where the otter whistles his mate, (They fear not men in the woods, Because they see so few) You will hear the beat of a horse’s feet, And the swish of a skirt in the dew, Steadily cantering through The misty solitudes, As though they perfectly knew The old lost road through the woods… But there is no road through the woods. -

Twas Brillig, and the Slithy Toves Did Gyre and Gimble in the Wabe; All Mimsy Were the Borogoves, and the Mome Raths Outgrabe

English Language Literature I - LETRAS - Prof. Daniel Derrel Santee - UFMS 2010 BRITISH By Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) `Twas brillig, and the slithy toves One, two! One, two! And through and through Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; The vorpal blade went snicker-snack! All mimsy were the borogoves, He left it dead, and with its head And the mome raths outgrabe. He went galumphing back. `Beware the Jabberwock, my son! `And has thou slain the Jabberwock? The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! Come to my arms, my beamish boy! Beware the Jujub bird, and shun O frabjous day! Calloh! Callay! The frumious Bandersnatch!' He chortled in his joy. He took his vorpal sword in hand: `Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Long time the manxome foe he sought -- Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; So rested he by the Tumtum gree, All mimsy were the borogoves, And stood awhile in thought. And the mome raths outgrabe. And as in uffish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, Came whiffling through the tulgey wook, And burbled as it came! Made More Stir Than Anything Else By Eleanor Graham "Jabberwocky", the strange nonsense poem those in Through The Looking Glass, so the transla- printed in Looking-Glass characters, made more stir tion read: "It was evening, and the smooth active than anything else in the book and some wild asser- badgers were scratching and boring holes in the hill- tions were made about its origin. The truth was, side, all unhappy were the parrots and the grave tur- however, that Dodgson had made up the first verse tles squeaked out". -

FSK-Freigabe- Bescheinigung

Freigabebescheinigung FSK FREIWILLIGE SELBSTKONTROLLE DER FILMWIRTSCHAFT GmbH Prüf-Nr.: 28197(VV) Video Der Bildträger Stereophonics - A Decade In The Sun Originaltitel - Programmanbieter Universal Music GmbH, Berlin Herstellungsland - Herstellungsjahr - Laufzeit 24fps: - 25fps: 145:56 wurde im Auftrag der Obersten Landesjugendbehörden von der FSK Freiwilligen Selbstkontrolle der Filmwirtschaft GmbH nach § 12 i.V.m. § 14 JuSchG geprüft. Die Prüfung hatte das Ergebnis, dass der Bildträger für die Altersstufe „Freigegeben ab 12 (zwölf) Jahren“ freigegeben werden kann. Wiesbaden, den 07.10.2008 Inhalt Laufzeit Freigabe More Life In A Tramp's Vest 002:17 o.Al. A Thousand Trees 003:11 ab 12 Traffic 004:20 o.Al. Local Boy In The Photograph 003:15 o.Al. The Bastard & The Thief 003:57 ab 6 Just Looking 004:06 ab 6 I Wouldn't Believe In Your Radio 004:09 ab 6 Hurry Up And Wait 004:28 ab 6 Mama Told Me Not To Come 004:38 o.Al. Mr. Writer 004:25 ab 12 Have A Nice Day 003:30 ab 6 Step On My Old Size Nines 003:57 o.Al. Handbags & Gladrags 004:38 o.Al. Vegas Two Times 003:33 o.Al. Madame Helga 003:59 o.Al. Maybe Tomorrow 005:54 ab 6 Since I Told You It's Over 003:58 o.Al. Moviestar 004:03 ab 6 Dakota 004:02 o.Al. Superman 003:52 ab 6 Devil 004:46 ab 12 Rewind 004:52 ab 6 It Means Nothing 003:40 o.Al. You're My Star 004:04 ab 6 I Wouldn't Believe Your Radio (Live) 005:15 o.Al. -

By Song Title

Solar Entertainments Karaoke Song Listing By Song Title 3 Britney Spears 2000s 17 MK 2010s 22 Lily Allen 2000s 39 Queen 1970s 679 Fetty Wap 2010s 711 Beyonce 2010s 1973 James Blunt 2000s 1999 Prince 1980s 2002 Anne Marie 2010s #ThatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 2010s 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & The Aces 1960s 1 800 273 8255 Logic & Alessia Cara & Khalid 2010s 1 Thing Amerie 2000s 10/10 Paolo Nutini 2010s 10000 Hours Dan & Shay & Justin Bieber 2010s 18 & Life Skid Row 1980s 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 1990s 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 2000s 20th Century Boy T Rex 1970s 21 Guns Green Day 2000s 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 2000s 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard 2000s 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 2010s 24K Magic Bruno Mars 2010s 2U David Guetta & Justin Bieber 2010s 3 AM Busted 2000s 3 Nights Dominic Fike 2010s 3 Words Cheryl Cole 2000s 30 Days Saturdays 2010s 34+35 Ariana Grande 2020s 4 44 Jay Z 2010s 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 2000s 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2000s 5 Colours In Her Hair McFly 2000s 5,6,7,8 Steps 1990s 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be) Proclaimers 1980s 7 Rings Ariana Grande 2010s 7 Things Miley Cyrus 2000s 7 Years Lukas Graham 2010s 74 75 Connells 1990s 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 1980s 90 Days Pink & Wrabel 2010s 99 Red Balloons Nena 1980s A Bad Dream Keane 2000s A Blossom Fell Nat King Cole 1950s A Change Would Do You Good Sheryl Crow 1990s A Cover Is Not The Book Mary Poppins Returns Soundtrack 2010s A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers 1990s A Different Beat Boyzone 1990s A Different Corner George Michael 1980s -

500 Drugstore Feat. Thom Yorke El President 499 Blink

500 DRUGSTORE FEAT. EL PRESIDENT THOM YORKE 499 BLINK 182 ADAMS SONG 498 SCREAMING TREES NEARLY LOST YOU 497 LEFTFIELD OPEN UP 496 SHIHAD BEAUTIFUL MACHINE 495 TEGAN AND SARAH WALKING WITH A GHOST 494 BOMB THE BASS BUG POWDER DUST 493 BAND OF HORSES IS THERE A GHOST 492 BLUR BEETLEBUM 491 DISPOSABLE HEROES TELEVISION THE DRUG OF THE OF... NATION 490 FOO FIGHTERS WALK 489 AIR SEXY BOY 488 IGGY POP CANDY 487 NINE INCH NAILS THE HAND THAT FEEDS 486 PEARL JAM NOT FOR YOU 485 RADIOHEAD EVERYTHING IN ITS RIGHT PLACE 484 RANCID TIME BOMB 483 RED HOT CHILI MY FRIENDS PEPPERS 482 SANTIGOLD LES ARTISTES 481 SMASHING PUMPKINS AVA ADORE 480 THE BIG PINK DOMINOS 479 THE STROKES REPTILIA 478 THE PIXIES VELOURIA 477 BON IVER SKINNY LOVE 476 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE MY GIRLS 475 FILTER HEY MAN NICE SHOT 474 BRAD 20TH CENTURY 473 INTERPOL SLOW HANDS 472 MAD SEASON SLIP AWAY 471 OASIS SOME MIGHT SAY 470 SLEIGH BELLS RILL RILL 469 THE AFGHAN WHIGS 66 468 THE FLAMING LIPS FIGHT TEST 467 ALICE IN CHAINS MAN IN THE BOX 466 FAITH NO MORE A SMALL VICTORY 465 THE THE DOGS OF LUST 464 ARCTIC MONKEYS R U MINE 463 BECK DEADWEIGHT 462 GARBAGE MILK 461 BEN FOLDS FIVE BRICK 460 NIRVANA PENNYROYAL TEA 459 SHIHAD YR HEAD IS A ROCK 458 SNEAKER PIMPS 6 UNDERGROUND 457 SOUNDGARDEN BURDEN IN MY HAND 456 EMINEM LOSE YOURSELF 455 SUPERGRASS RICHARD III 454 UNDERWORLD PUSH UPSTAIRS 453 ARCADE FIRE REBELLION (Lies) 452 RADIOHEAD BLACK STAR 451 BIG DATA DANGEROUS 450 BRAN VAN 3000 DRINKING IN LA 449 FIONA APPLE CRIMINAL 448 KINGS OF LEON USE SOMEBODY 447 PEARL JAM GETAWAY 446 BEASTIE