Rhythm in the Speech and Music of Jazz and Riddim Musicians Angela C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Imaginary, Identity and Representation: the Case of Gentleman the German Reggae Luminary

Ali 1 Musical Imaginary, Identity and Representation: The Case of Gentleman the German Reggae Luminary A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction in Comparative Studies in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University By Raghe Ali April 2013 The Ohio State University Project Advisors Professor Barry Shank, Department of Comparative Studies Professor Theresa Delgadillo, Department of Comparative Studies Ali 2 In 2003 a German reggae artist named Gentleman was scheduled to perform at the Jamworld Entertainment Center in the south eastern parish of St Catherine, Jamaica. The performance was held at the Sting Festival an annual reggae event that dates back some twenty years. Considered the world’s largest one day reggae festival, the event annually boasts an electric atmosphere full of star studded lineups and throngs of hardcore fans. The concert is also notorious for the aggressive DJ clashes1 and violent incidents that occur. The event was Gentleman’s debut performance before a Jamaican audience. Considered a relatively new artist, Gentleman was not the headlining act and was slotted to perform after a number of familiar artists who had already “hyped” the audience with popular dancehall2 reggae hits. When his turn came he performed a classical roots 3reggae song “Dem Gone” from his 2002 Journey to Jah album. Unhappy with his performance the crowd booed and jeered at him. He did not respond to the heckling and continued performing despite the audience vocal objections. Empty beer bottles and trash were thrown onstage. Finally, unable to withstand the wrath and hostility of the audience he left the stage. -

Lila Iké | Biography Lila Ike (Pronounced Lee-Lah Eye-Kay) Is on the Brink of Stardom. the 26-Year-Old Jamaican Songbird

Lila Iké | Biography Lila Ike (pronounced Lee-lah Eye-kay) is on the brink of stardom. The 26-year-old Jamaican songbird has an edge and ease in her voice that creates an immediate gravitational pull with her listener, fusing contemporary reggae with elements of soul, hip-hop and dancehall. The free-spirited, easy-going singer has already released a handful of velvety smooth songs through In.Digg.Nation Collective, a record label and talent pool for Jamaican creatives, founded by reggae star Protoje. The ExPerience will be Lila Iké’s debut EP for Six Course/RCA Records in a new partnership with In.Digg.Nation Collective. She breathes a delicate testimony of love, infatuation, and spiritual guidance in the 7-track release out this Spring. The EP is padded with previously-released songs such as “Where I’m Coming From” and “Second Chance.” Pivoting from the singles that earned her international acclaim in 2018 and 2019, Lila Iké unveils playful seduction on “I Spy,” her first release of 2020 produced by Izy Beats (the hitmaker behind Koffee’s “Toast”). Beckoning with innocent flirtation over soft guitar licks, Lila in a sweet falsetto sings, “I spy I spy, that you see something you might like. Won’t you come over if you really mean it.” The layers to Lila are in full bloom as she opens up about the daily pressures she faces through her interaction with people and wanting peace of mind in “Solitude” — . On “Stars Align,” Lila flips the instrumental from Protoje’s “Bout Noon” into an anthem about falling in love through the metaphor of making music. -

Read Or Download

afrique.q 7/15/02 12:36 PM Page 2 The tree of life that is reggae music in all its forms is deeply spreading its roots back into Afri- ca, idealized, championed and longed for in so many reggae anthems. African dancehall artists may very well represent the most exciting (and least- r e c o g n i z e d ) m o vement happening in dancehall today. Africa is so huge, culturally rich and diverse that it is difficult to generalize about the musical happenings. Yet a recent musical sampling of the continent shows that dancehall is begin- ning to emerge as a powerful African musical form in its own right. FromFrom thethe MotherlandMotherland....Danc....Danc By Lisa Poliak daara-j Coming primarily out of West Africa, artists such as Gambia’s Rebellion D’Recaller, Dancehall Masters and Senegal’s Daara-J, Pee GAMBIA Froiss and V.I.B. are creating their own sounds growing from a fertile musical and cultural Gambia is Africa’s cross-pollination that blends elements of hip- dancehall hot spot. hop, reggae and African rhythms such as Out of Gambia, Rebel- Senegalese mbalax, for instance. Most of lion D’Recaller and these artists have not yet spread their wings Dancehall Masters are on the international scene, especially in the creating music that is U.S., but all have the musical and lyrical skills less rap-influenced to explode globally. Chanting down Babylon, than what is coming these African artists are inspired by their out of Senegal. In Jamaican predecessors while making music Gambia, they’re basi- that is uniquely their own, praising Jah, Allah cally heavier on the and historical spiritual leaders. -

Outsiders' Music: Progressive Country, Reggae

CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s Chapter Outline I. The Outlaws: Progressive Country Music A. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, mainstream country music was dominated by: 1. the slick Nashville sound, 2. hardcore country (Merle Haggard), and 3. blends of country and pop promoted on AM radio. B. A new generation of country artists was embracing music and attitudes that grew out of the 1960s counterculture; this movement was called progressive country. 1. Inspired by honky-tonk and rockabilly mix of Bakersfield country music, singer-songwriters (Bob Dylan), and country rock (Gram Parsons) 2. Progressive country performers wrote songs that were more intellectual and liberal in outlook than their contemporaries’ songs. 3. Artists were more concerned with testing the limits of the country music tradition than with scoring hits. 4. The movement’s key artists included CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s a) Willie Nelson, b) Kris Kristopherson, c) Tom T. Hall, and d) Townes Van Zandt. 5. These artists were not polished singers by conventional standards, but they wrote distinctive, individualist songs and had compelling voices. 6. They developed a cult following, and progressive country began to inch its way into the mainstream (usually in the form of cover versions). a) “Harper Valley PTA” (1) Original by Tom T. Hall (2) Cover version by Jeannie C. Riley; Number One pop and country (1968) b) “Help Me Make It through the Night” (1) Original by Kris Kristofferson (2) Cover version by Sammi Smith (1971) C. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

The Spirit of Dancehall: Embodying a New Nomos in Jamaica Khytie K

The Spirit of Dancehall: embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown Transition, Issue 125, 2017, pp. 17-31 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/686008 Access provided by Harvard University (20 Feb 2018 17:21 GMT) The Spirit of Dancehall embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown As we approached the vicinity of the tent we heard the wailing voices, dominated by church women, singing old Jamaican spirituals. The heart beat riddim of the drums pulsed and reverberated, giving life to the chorus. “Alleluia!” “Praise God!” Indecipherable glossolalia punctu- ated the emphatic praise. The sounds were foreboding. Even at eleven years old, I held firmly to the disciplining of my body that my Catholic primary school so carefully cultivated. As people around me praised God and yelled obscenely in unknown tongues, giving their bodies over to the spirit in ecstatic dancing, marching, and rolling, it was imperative that I remained in control of my body. What if I too was suddenly overtaken by the spirit? It was par- ticularly disconcerting as I was not con- It was imperative that vinced that there was a qualitative difference between being “inna di spirit I remained in control [of God]” and possessed by other kinds of my body. What if of spirits. I too was suddenly In another ritual space, in the open air, lacking the shelter of a tent, heavy overtaken by the spirit? bass booms from sound boxes. The seis- mic tremors radiate from the center and can be felt early into the Kingston morning. -

1 Julian Henriques Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems

Julian Henriques Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques & Ways of Knowing Preamble: Thinking Through Sound It hits you, but you feel no pain, instead, pleasure.1 This is the visceral experience of audition, to be immersed in an auditory volume, swimming in a sea of sound, between cliffs of speakers towering almost to the sky, sound stacked up upon sound - tweeters on top of horns, on top of mid, on top of bass, on top of walk-in sub bass bins (Frontispiece). There is no escape, not even thinking about it, just being there alive to, in and as the excess of sound. Trouser legs flap to the base line and internal organs resonate to the finely tuned frequencies, as the vibrations of the music excite every cell in your body. This is what I call sonic dominance.2 This explodes with all the multi sensory intensity of image, touch, movement and smell - the dance crews formations sashaying across the tarmac in front of the camera lights, the video projection screens and the scent of beer rum, weed, sweat and drum chicken floating on the tropical air. The sound of the reggae dancehall session calls out across the city blocks, or countryside hills to draw you in. It brings you to yourself, to and through your senses and it brings you to and with others sharing these convivial joys - out on the street under the stars in downtown Kingston, Jamaica. Such a scene is literally the dance of the sonic bodies to which this book attends. Sonic bodies are fine-tuned, as with the phonographic instrument of the sound system “set” of equipment. -

For Immediate Release Papa Rosko Announces Debut

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PAPA ROSKO ANNOUNCES DEBUT ALBUM OUT OCTOBER 16, 2020 THE SELF‐TITLED ALBUM FUSES REGGAE WITH ELEMENTS OF ROCK, POP, LATIN, AND COUNTRY MUSIC FEATURES COLLABS WITH REGGAE LEGENDS TOOTS & THE MAYTALS, DANCEHALL STAR GYPTIAN, AND THIRD WORLD LEAD SINGER AJ BROWN Introducing the multi-genre recording and performing artist Papa Rosko, who will be releasing his self-titled debut album on October 16, 2020. Papa Rosko pulls together a wide spectrum of genres on his debut album, fusing elements of rock, pop, alternative, Latin, and country music into a seamless reggae sound. The self-titled album was recorded over the course of two and half years between studios in South Florida and Kingston, Jamaica. The results are an impressive album filled with original songs and a pair of country-reggae fusion covers featuring reggae and dancehall legends. The album kicks off with Papa Rosko’s take on the classic Johnny Cash song “Folsom Prison Blues,” featuring Toots Hibbert of Toots & the Maytals as special guest vocalist (Toots famously wrote his own prison song “54-46 That’s My Number,” which gets a shout out at the end of the song here.) Another cover on the album is of the timeless song “When You Say Nothing At All,” featuring Jamaican dancehall star Gyptian as guest vocalist. The song has been an international hit for three different artists (Keith Whitley, Alison Krauss & Union Station, Ronan Keating) spanning three different decades. The iconic tune has always been done as a slow ballad, but Papa Rosko brings his unique style to it, picking up the tempo and immersing it in an island vibe. -

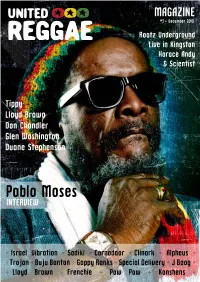

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

Jazzweek World Music Albums Feb

airplay data JazzWeek World Music Albums Feb. 2, 2009 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 24 – 1 Hendrik Meurkens Samba To Go! Zoho 130 28 102 2 48 36 2 4 7 2 Novalima Coba Coba Cumbancha 116 100 16 5 37 10 3 5 4 2 The Wayne Wallace Latin Jazz Quintet Infinity Patois 97 100 -3 12 41 2 4 6 5 1 Taj Mahal Maestro Kan-Du/Heads Up 77 83 -6 18 33 0 5 20 74 5 Cocoa Tea Barack Obama [Single] Roaring Lion/VP 76 34 42 16 47 16 6 8 11 3 Femi Kuti Day By Day Mercer Street 63 67 -4 12 26 0 7 9 13 2 Buena Vista Social Club Buena Vista Social Club At Carnegie Hall World Circuit/Nonesuch 58 66 -8 16 23 1 8 13 12 1 Various Artists The Biggest Reggae One-Drop Anthems Greensleeves 51 48 3 7 24 0 2008 9 18 – 9 Mark Weinstein Lua E Sol Jazzheads 48 37 11 2 29 16 10 15 8 6 Various Artists Strictly The Best 39 VP 47 40 7 7 30 0 11 43 30 1 Hot Club Of Detroit Night Town Mack Avenue 46 19 27 32 37 0 12 48 – 12 Beausoleil Alligator Purse Yep Rock 45 18 27 2 21 14 13 32 26 1 Burning Spear Jah Is Real Burning 44 22 22 25 14 0 14 27 17 7 Beres Hammond A Moment In Time VP 39 26 13 26 27 0 15 11 14 3 El Guincho Alegranza XL 38 54 -16 13 14 1 15 10 10 5 Randy Brecker Randy In Brasil MAMA 38 61 -23 20 10 0 17 7 40 7 The Very Best Esau Mwamwaya + Radioclit : The Very Best Green Owl 37 68 -31 3 21 9 18 25 22 13 Senor Coconut And His Orchestra Around The World Essay/Nacional 32 27 5 13 16 1 19 – – 19 Chango Spasiuk Pynandi - Los Descalzos Harmonia Mundi/World 31 0 0 1 30 30 Village 20 17 3 2 Various Artists Calypsoul 70: Caribbean Soul -

Black Prophet

Fomjam-Music Page 1 of 4 Black Prophet Black Prophet is an Afro - Reggae artist from Ghana and is among one of the first musicians who made conscious reggae from Ghana internationally known. His unique, harmonious reggae beat combined with a glamorous African cadence offers a very distinctive sound to his rhythm. This text will be replaced Repertoire: file://C:\FJ_WEB\Black_Prophet\Black_Prophet.htm 15.01.2013 Fomjam-Music Page 2 of 4 Reggae Biografie: In 2003, the singer and songwriter made his first tour to Europe, where he played on various festivals in the Netherlands and Belgium. In 2006 he released the Album ‘Legal Stranger’ which contains besides hits like ‘Mama Africa’ and ‘Tell me why’ the song ‘Doubting me’ which was nominated ‘Best reggae song of the year’ at the Ghana national Music Awards. In 2008 his third album “Prophecy” was published which was a compilation of powerful songs such as “No pain no gain”, “Give me back all the natural resources” or the hit tune “Hot and Cold” featuring the British – Ghanaian Rapper Sway. As his reputation further grew across continental Europe, Black Prophet has been constantly invited to play at various shows and festivals, such as the Oland Roots festival (Sweden), Rottodom Sunsplash Festival (Spain), Reggae Geel Festival (Belgium) or the Rastaplas Festival (Netherlands). In 2010 the gifted reggae artist won the Benelux – Final of the European Reggae Contest. During his latest European tour with the Jamaican Artist Turbulence in February 2012 the conscious reggae musician showcased his newest album “Tribulations” which offers a unique fusion of African and Jamaican Reggae elements with traditional African music and hip – hop beats.