The Implementation of the Korean Green Growth Strategy in Urban Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area 2013. 11. Presenter : Dr. Sang Keon Lee Co-author: Dr. Sang Min Lee(KOTI) General Information Seoul (Area=605㎢, 10mill. 23.5%) - Population of South Korea : 51.8 Million (‘13) Capital Region (Area=11,730㎢, 25mill. 49.4%)- Size of South Korea : 99,990.5 ㎢ - South Korean Capital : Seoul 2 Ⅰ. Major changes of recent decades in Korea Korea’s Pathways at a glance 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Economic Economic Heavy-Chem. Stabilization-Growth- Economic Crisis & Post-war recovery Development takeoff Industry drive Balancing-Deregulation Restructuring Development of Balanced Territorial Post-war Growth pole Regional growth Promotion Industrialization regional Development reconstruction development Limit on urban growth base development Post-war Construction of Highways & National strategic networks Environ. friendly Transport reconstruction industrial railways Urban subway / New technology 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Population 20,189 24,989 31,435 37,407 43,390 45,985 48,580 (1,000 pop.) GDP - 1,154 1,994 3,358 6,895 11,347 16,372 ($) No. Cars - - 127 528 3,395 12,059 17,941 (1,000 cars) Length of 25,683 27,169 40,244 46,950 56,715 88,775 105,565 Road(km) 3 Population and Size - Seoul-Metropoliotan Area · Regions : Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi · Radius : Seoul City 11~16 km Metro Seoul 4872 km Population Size Density (million) (㎢) (per ㎢) Seoul 10.36 605.3 17,115 Incheon 2.66 1,002.1 2,654 Gyeonggi 11.11 10,183.3 1,091 Total 24.13 11,790.7 2,047 4 III. -

Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-Do & Seoul Metropolitan Area

Gyeongchun line Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-do & Seoul Metropolitan Area Hoeryong Uijeongbu Ganeung Nogyang Yangju Deokgye Deokjeong Jihaeng DongducheonBosan Jungang DongducheonSoyosan Chuncheon Mangwolsa 1 Starting Point Destination Dobongsan 7 Namchuncheon Jangam Dobong Suraksan Gimyujeong Musan Paju Wollong GeumchonGeumneungUnjeong TanhyeonIlsan Banghak Madeul Sanggye Danngogae Gyeongui line Pungsan Gireum Nowon 4 Gangchon 6 Sungshin Baengma Mia Women’s Univ. Suyu Nokcheon Junggye Changdong Baekgyang-ri Dokbawi Ssangmun Goksan Miasamgeori Wolgye Hagye Daehwa Juyeop Jeongbalsan Madu Baekseok Hwajeong Wondang Samsong Jichuk Gupabal Yeonsinnae Bulgwang Nokbeon Hongje Muakjae Hansung Univ. Kwangwoon Gulbongsan Univ. Gongneung 3 Dongnimmun Hwarangdae Bonghwasan Sinnae (not open) Daegok Anam Korea Univ. Wolgok Sangwolgok Dolgoji Taereung Bomun 6 Hangang River Gusan Yeokchon Gyeongbokgung Seokgye Gapyeong Neunggok Hyehwa Sinmun Meokgol Airport line Eungam Anguk Changsin Jongno Hankuk Univ. Junghwa 9 5 of Foreign Studies Haengsin Gwanghwamun 3(sam)-ga Jongno 5(o)-gu Sinseol-dong Jegi-dong Cheongnyangni Incheon Saejeol Int’l Airport Galmae Byeollae Sareung Maseok Dongdaemun Dongmyo Sangbong Toegyewon Geumgok Pyeongnae Sangcheon Banghwa Hoegi Mangu Hopyeong Daeseong-ri Hwajeon Jonggak Yongdu Cheong Pyeong Incheon Int’l Airport Jeungsan Myeonmok Seodaemun Cargo Terminal Gaehwa Gaehwasan Susaek Digital Media City Sindap Gajwa Sagajeong Dongdaemun Guri Sinchon Dosim Unseo Ahyeon Euljiro Euljiro Euljiro History&Culture Park Donong Deokso Paldang Ungilsan Yangsu Chungjeongno City Hall 3(sa)-ga 3(sa)-ga Yangwon Yangjeong World Cup 4(sa)-ga Sindang Yongmasan Gyeyang Gimpo Int’l Airport Stadium Sinwon Airprot Market Sinbanghwa Ewha Womans Geomam Univ. Sangwangsimni Magoknaru Junggok Hangang River Mapo-gu Sinchon Aeogae Dapsimni Songjeong Office Chungmuro Gunja Guksu Seoul Station Cheonggu 5 Yangcheon Hongik Univ. -

Choosing the Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing the Right Location

Choosing The Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing The Right Location Geography The Korean Peninsula lies in the north-eastern part of the Asian continent. It is bordered to the north by Russia and China, to the east by the East Sea and Japan, and to the west by the Yellow Sea. In addition to the mainland, South Korea comprises around 3,200 islands. At 99,313 sq km, the country is slightly larger than Austria. It has one of the highest population densities in the world, after Bangladesh and Taiwan, with more than 50% of its population living in the country’s six largest cities. Korea has a history spanning 5,000 years and you will find evidence of its rich and varied heritage in the many temples, palaces and city gates. These sit alongside contemporary architecture that reflects the growing economic importance of South Korea as an industrialised nation. In 1948, Korea divided into North Korea and South Korea. North Korea was allied to the, then, USSR and South Korea to the USA. The divide between the two countries at Panmunjom is one of the world’s most heavily fortified frontiers. Copyright © 2013 IMA Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Generated from http://www.southkorea.doingbusinessguide.co.uk/the-guide/choosing-the-right- location/ Tuesday, September 28, 2021 Choosing The Right Location Page 2 of 4 Surrounded on three sides by the ocean, it is easy to see how South Korea became a world leader in shipbuilding. Climate South Korea has a temperate climate, with four distinct seasons. Spring, from late March to May, is warm, while summer, from June to early September is hot and humid. -

Republic of Korea Hoeyang Lake

1 1 1 1 1 2 S2 unchon 2 2 2 5 6 7 8 9 ? Sukchon ? Sinchang-ni ? ? ? Pyongwon Sunan Okpyong-ni Songchon National Capital Kangdong Yangdok Yangdog-up Wonsan Pyongyang Provincial Capital ? City, town ? 9 Sungho-dong 9 3 Major Airport 3 Roads Chunghwa Nampo Democratic People's Railroad Songnim River Hwangju Republic of Korea Hoeyang Lake Anag-up International Boundary Anak Sariwon Demarcation Line Hungsu-ri Pyonggang Sinchon Chaeryong Sinmak Provincial Boundary Changyon 0 5 10 20 30 40 Ayang-ni Kilometers Miles Haeju 0 4 8 16 24 32 ? ? 8 Kaesong 8 3 Pyoksong 3 Dongducheon Ongjin Chuncheon SEA OF Sigyo-ri Gangneung Euijeongbu JAPAN Hongcheon Seoul KANG-WON-DO Mugho Bucheon SEOUL Samcheog Incheon Hoengseon Anyang KYONGGI-DO INCHON Weonju Jeongseon Suweon Jecheon Osan Yeongweol Chechon ? Pyeongtaeg Jungju ? 7 7 3 3 Eumseong Chungju CHUNGCHONGBUK-DO Cheonan Yeongju Oncheon-ri CHUNGCHONGNAM-DO Yeongyang Yesar Jeoneui Cheongju Hongseong Jeomchon Yecheon Cwangcheon Hamchang Andong Yeonghae TAEJON KYONGSANGBUK-DO Gongju Sangju Yeongdeog Daecheon Daejeon Euiseong Gyuam Buyeo Ogcheon Nonsan Seonsan Gunwi Ganggyeong Yeanmudae Yeongdong Gimcheon Seocheon Gumi Jacheon Pohang ? Geumsan Yangmog ? 6 6 3 Janghang 3 YELLOW SEA Muju Yeongcheon Kunsan Gunsan TAEGU Samnye Taegu Hayang RJeoenjupublic of KoreaDaegu Gyeongsan Gyeongju Gimje Jinan Janggye Geochang Goryeong CHOLLABUK-DO Hyeopung Cheongdo Aneui Ulsan Byeongyeong Hahcheon Changyeong Eonyang Hamyang Miryang Bangeojin Sancheong Gimhae Yangsan KWANGJU KYONGSANGNAM-DO Gupo Jinju Masan Kwangju Jinhae Pusan Sacheon Ungcheon ? Naju Chinhae ? 5 5 3 Goseong PUSAN 3 Yeongsanpo Suncheon CHOLLANAM-DO Samcheongpo Mogpo KOREA STRAIGHT Yeongam Beqlgyo Namhae Byeongyeong Yeosu Gangjin Jangheung Haenam Jindo ? ? 4 4 3 3 Repu blic Cheju Jeju of Korea Seogwipo Moseulpo Maetsuyoshi CHEJU-DO ? JAPAN ? 3 3 3 3 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Fukue Tomie ? ? ? ? ? 5 6 7 8 9 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Contact Details of the Support Centers for Foreign Workers in the Republic of Korea Name of the Center Region Tel

Contact details of the Support Centers for Foreign Workers in the Republic of Korea Name of the Center Region Tel. Shelter facilities Seoul Migrant Workers Center Seoul 02-3672-9472 ✓ Seoul Migrant Workers House/Korean Chinese Seoul 02-863-6622 ✓ House Sungdong Migrant Workers Center Seoul 02-2282-7974 Elim Mission Center Seoul 02-796-0170 Association for Foreign Migrant Workers Human Seoul 02-795-5504 Rights Yongsan Nanum House Seoul 02-718-9986 ✓ Won Buddism Seoul Foregin Center for Migrant Seoul 02-2699-9943 Workers Migrant Workers Welfare Society Seoul 02-858-4115 With community Migrant Center Gangwon 070-7521-8097 ✓ Osan Migrant Workers Center Osan 031-372-9301 ✓ Pyeongtek Migrant workers Center Pyeongtaek 031-652-8855 ✓ Bucheong Migrant Workers Center Wonmi 032-654-0664 ✓ Korea Migration Foundation Gwanju 031-797-2688 ✓ Cathalic Diocese of Ujeongbu Executive Center Guri 031-566-1142 ✓ EXODUS Gimpo Immigration Center Gimpo 031-982-7661 Anyang immigration Center Anyang 031-441-8502 ✓ Ansan Foreign Workers Support Center 031-4750-111 Ansan Foreign Workers house Ansan 031-495-2288 ✓ Kyungdong Presbyterian Church Pohan 054-291-0191 ✓ Catholic Diocese of Masan Migrant Committee Changwon 055-275-8203 Immigration center Changwon Gumi Maha Migrant Center Gumi 052-458-0755 Sungnam Migrant Workers House/Korean- Kyunggi ,Sung 031-756-2143 Chinese House nam Foreign Workers Cultural Center Gwangju 062-943-8930 ✓ Catholic Social welfare immigrants Pastoral in Gwangju 062-954-8003 ✓ Gwanju Gwnagju Migrant Workers Center Gwangju 062-971-0078 Daejeong -

![Rubber Flooring Sales Record [Korea] 2013-2009](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1221/rubber-flooring-sales-record-korea-2013-2009-491221.webp)

Rubber Flooring Sales Record [Korea] 2013-2009

1/16 Rubber Flooring Sales Record [Korea] 2013-2009 ◐ Part of Public Facilities (more than 180 in total) 2013.12. updated No. Application Year/ Month Location Project No. Application Year/ Month Location Project 1 Public 2013.08 Incheon Haksan Culture Foundation 32 Airport 2011.06 Gyeonggi Gimpo Airport International line 2 facilities 2012.02 Seosan Sweage Treatment Plant 33 facilities 2009.11 Seoul Gimpo Airport 3 2011.12 Seoul Lifelong Learning Center 34 2008.10 Incheon Incheon International Airport 4 2011.12 Chungnam Chungnam Sweage Treatment Plant 35 Government 2013.10 Seoul Yeongdeungpo Post Office 5 2011.08 Gyeonggi Gyeonggi Workforce Development Center 36 office 2013.07 Ansan Ansan Credit Guarantee Funds 6 2010.12 Seoul Eunpyeong Child Development Center 37 2013.07 Daejeon National Fusion Research Institute 7 2010.12 Chonnam Naro Space Center 38 2013.07 Cheongju Cheongju Cultural Center 8 2009.12 Gyeongbuk Uljin Sweage Treatment Plant 39 2013.06 Daejeon Credit Guarantee Funds 9 2009.11 Chungbuk Yeongdong Waste Disposal 40 2013.06 Bucheon Bucheon City Hall 10 2009.11 kangwon Chuncheon Women's Center 41 2013.06 Busan National Oceanographic Research Institute 11 2009.08 Gyeonggi Munsan Filtration Plant 42 2013.05 Chilgok Chilgok Counties Center 12 Cultural 2013.08 Ulsan Hyundai Motor Co., Cultural Center 43 2013.01 Seoul Gangseo Office of Education 13 facilities 2013.07 Gwacheon Gwacheon National Science Museum 44 2013.01 Daegu Daegu Suseong-gu(ward) Office 14 2012.11 Daegu Student Cultural Center 45 2012.12 Jeungpyeong Jeungpyeong -

Jeju Island Rambling: Self-Exile in Peace Corps, 1973-1974

Jeju Island Rambling: Self-exile in Peace Corps, 1973-1974 David J. Nemeth ©2014 ~ 2 ~ To Hae Sook and Bobby ~ 3 ~ Table of Contents Chapter 1 Flying to Jeju in 1973 JWW Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1, 2013) ~17~ Chapter 2 Hwasun memories (Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 2 (January 8, 2013) ~21~ Chapter 3 Hwasun memories (Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 3 (January 15, 2013) ~25~ Chapter 4 Hwasun memories (Part 3) JWW Vol. 1, No. 4 (January 22, 2013) ~27~ Chapter 5 The ‘Resting Cow’ unveiled (Udo Island Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 5 (January 29, 2013) ~29~ Chapter 6 Close encounters of the haenyeo kind (Udo Island Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 6 (February 5, 2013) ~32~ Chapter 7 Mr. Bu’s Jeju Island dojang (Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 7 (February 12, 2013) ~36~ Chapter 8 Mr. Bu’s dojang (Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 8 (February 19, 2013) ~38~ Chapter 9 Mr. Bu’s dojang (Part 3) JWW Vol. 1, No. 9 (February 26, 2013) ~42~ Chapter 10 Mr. Bu’s dojang (Part 4) JWW Vol. 1, No. 10 (March 5, 2013) ~44~ Chapter 11 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 11 (March 12, 2013) ~46~ Chapter 12 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 12 (March 19, 2013) ~50~ Chapter 13 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 3) JWW Vol. 1, No. 13 (March 26, 2013) ~55~ Chapter 14 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 4) JWW Vol. -

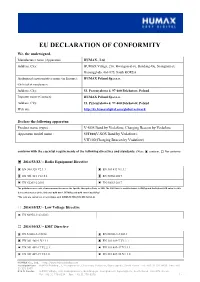

EC Declaration of Conformity

EU DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY We, the undersigned, Manufacturer name (Apparatus) HUMAX., Ltd Address, City: HUMAX Village, 216, Hwangsaeul-ro, Bundang-Gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, 463-875, South KOREA Authorized representative name (in Europe): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. (On behalf of manufacturer) Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Importer name (Contact): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Web site http://kr.humaxdigital.com/global-network Declare the following apparatus: Product name (type) : V-SOS Band by Vodafone, Charging Beacon by Vodafone Apparatus model name : VIT100(V-SOS Band by Vodafone), VIT100(Charging Beacon by Vodafone) conform with the essential requirements of the following directives and standards: (Note: ▣ conform, □ Not conform) ▣ 2014/53/EU - Radio Equipment Directive ▣ EN 300 328 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 303 413 V1.1.1 ▣ EN 301 511 V12.5.1 ▣ EN 50566:2017 ▣ EN 62209-2:2010 ▣ EN 50663:2017 The guidelines use a unit of measurement known as the Specific Absorption Rate, or SAR. The SAR limit for mobile devices is 4W/kg and the highest SAR value for this device when tested at the limb was GSM 900 1.567W/kg and GSM 1800 1.922W/kg*. *The tests are carried out in accordance with [CENELEC EN50566] [IEC 62209-2]. □ 2014/35/EU - Low Voltage Directive ▣ EN 60950-1/A2:2013 □ 2014/30/EU - EMC Directive ▣ EN 61000-3-2:2014 ▣ EN 61000-3-3:2013 ▣ EN 301 489-1 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-7 V1.3.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V2.2.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V3.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-19 V2.1.0 ▣ EN 301 489-52 V1.1.0 HUMAX Co., Ltd. -

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea's Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Jeongmuk Kang Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Uppsala University, Department of Earth Sciences Master Thesis E, in Sustainable Development, 30 credits Printed at Department of Earth Sciences, Master’s Thesis Geotryckeriet, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2012. E, 30 credits Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Supervisor: Gloria Gallardo Evaluator: Anders Larsson Contents List of Tables ......................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................ iii Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. -

GS Energy Brochure Download

Company Introduction COPYRIGHT © 2012 GS ENERRGY. All RIGHTS RESERVED GS Energy Profile p.03 Subsidiaries p.04 Business Portfolio Refining & Petrochemicals p.05 Gas & Power p.07 Exploration & Production p.12 Green Growth p.14 GS Energy R&D Center p.18 Financial Information p.19 Contact Us p.20 History p.21 COPYRIGHT © 2012 GS ENERRGY. All RIGHTS RESERVED Corporate Profile GS Energy was incorporated on January 3, 2012 as a result of GS Holdings’ spinoff of GS Caltex, its refining, marketing, chemicals and transportation arm, creating a new independent Korean energy company. Subsequently, GS Energy assumed the high growth businesses previously operated by GS Caltex including, exploration & production and renewable energy operations. Further, by acquiring GS Caltex’s electric & gas utilities operations, GS Energy has solidified its position as an integrated energy-specialized holding company. Value chain integration and operational agility are fundamental to GS Energy’s long term growth strategy. GS Energy is organized into four interrelated segments: Exploration & Production, Refining & Petrochemicals, Gas & Power and Green Growth. Our integrated business model allows us to capture synergies among our different segments and activities. Our upstream businesses include the development of oil & gas projects across the globe, from the Middle East to the Americas and Southeast Asia. Further downstream, GS Energy is currently constructing a Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminal in South Chungcheong Province to optimize value chain integration and to ultimately provide a steady flow of electric power and gas to customers through various subsidiaries and affiliates. Furthermore, given our focus on sustainable growth, we have been actively developing our technical know-how in the alternative energy sector. -

World Bank Document

.) SC'13 -1 L:;lPA._ E. Public Disclosure Authorized LSUrSD Lic) C..L\.JI8 | YNLF Pt{FORAANCU OF LOCAL GUVBRNAENTS LI TIUE <~)(EGLOt'4: ftiF_'LC: PIUJNS £00. LIeA ECO&CE 1ITRATfUNq POIC,IU Public Disclosure Authorized by Douig t,oon Chlu Kvung-iLan Kim and Kyu 3ik Lee Public Disclosure Authorized November 1985 et-r Spply -m- b Deve lor.n)-etLt De p aC:ie Up.raIL`ons t-3licy Staff Thle. -iorid Barl Public Disclosure Authorized LL- r t:C L c -eUi, ct :3 ;-;i 'I.-,1U E oLf)i.s lin n. t ; - ''.-.oip- r.....-.i id-'E ; . .-it0l¢.'', ''41. Doio. ilooni Cr!uni. Associate Prof&ssor of -conroinicu at K(,ailng, iee UJniversity, Seoul, worked on this paper w7hiik he 1J7as a consultant at the 'lorld Bank. ry.-un';g-A{wan Kim is a Ph.D. candidate in Economrics at Princ,aon University. Kyu Sik Lee, a :Senior E ':oiomist in the Water Supply and Urban DeveloumeTit, The World B3ank, s rectcd tne industrial Locatiton Policies Research Project. Kyuee-ria Pehk participated in compiling various data used. MIrs. Morallina F. George typed the manuscript. .L\ies'-: aLCc Project No . RPo 672-91 .LK.esaeLcl Project Name: An Evaluation of Industrial Location Policies for Urban Deconcentration Abstract This paper analyzes the avai Lable data on local finances for Seoul and its satellite cities. The paper documents the trends of revenues and expenditures for 1973-1982 to study the fiscal performance of individual local governments compared with that of Seoul. The findings indicate that the rapidly growing satellite cities outperformed Seoul in terms of their ability to generate revenues owing largely to thte increased tax bases. -

Air Quality Measures in South Korea

Air Quality Measures South Korea 2016.12 Ministry of Environment Current Air Quality Status in South Korea Ministry of Environment Current Air Quality Status in South Korea According to NASA Satellite Air Quality Map*, South Korea is one of the most concerned countries regarding air pollution (averaged over 2014). * Its major index is NOx mostly caused by power plants and automobiles. Source: NASA Source: NASA Current Air Quality Status in South Korea Transboundary particles Influence from Neighboring Countries exacerbate Korea’s PM concentrations (Source: OECD performance review draft) For an high concentration episode (24 Feb 2014), the contribution rate of neighboring countries was analyzed as 51.94%(Source: KOSAE) * Besides, high population density and rapid industrialization led high density of fine dust Source: Korean Society for Atmospheric Environment(KOSAE) Current Air Quality Status in South Korea In terms of premature deaths caused by outdoor air pollution, South Korea is one the vulnerable countries. Premature Deaths from Outdoor Air Pollution(Unit: deaths per 100,000 capita) 80 70 76 60 50 40 49 30 33 20 23 24 10 17 12 0 Korea Japan China India USA Germany France Source: WHO(2016), Ambient Air Pollution: A Global Assessment ofSource: exposure NASA and burden of disease Source Analysis on PM2.5 Ministry of Environment Source Analysis on PM2.5 With aggravating air pollution, Korea puts an high importance on clear cause analysis (domestic sources + influence from other countries) in preparing actions to improve its aggravating air quality. • Domestic polluting-sources Baecknyeongdo Emission statistics Seoul Super-Sites (Intensive monitoring station network) Daejeon Based on the dedicated information Ulsan above, secondary formation and Gwangju contribution rate of each local part are also reflected in preparing actions.