Coastal Kayak Instructor Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix S6 Benthic Habitat Mapping of the Darwin Region

Technical Appendix S6 Ichthys Gas Field Development Project: benthic habitat mapping of the Darwin region—methods of data collection, collation and map production Ichthys Gas Field Development Project: Benthic Habitat Mapping of the Darwin Region— Methods of data collection, collation and map production Rev 0 | 30 March 2011 INPEX Document No. C036-AH-REP-0121 Phone: +61 408 857 056 E-mail: [email protected] Address: 8/260 West Coast Highway Scarborough, WA Web: www.geooceans.com Table of Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................................5 2. Data collection methods ........................................................6 2.1. Towed video survey ................................................................................... 6 2.1.1. Field sampling ............................................................................................ 6 2.1.2. Video transects .......................................................................................... 6 2.1.3. Towed video system .................................................................................. 6 2.1.4. Video data analysis and habitat classification............................................ 7 2.1.5. Quality assurance and quality control ........................................................ 9 2.1.6. Bathymetry ................................................................................................. 9 2.1.7. Depth correction for tide.......................................................................... -

Tide Simplified by Phil Clegg Sea Kayaking Anglesey

Tide Simplified By Phil Clegg Sea Kayaking Anglesey Tide is one of those areas that the more you learn about it, the more you realise you don’t know. As sea kayakers, and not necessarily scientists, we don’t have to know every detail but a simplified understanding can help us to understand and predict what we might expect to see when we are out on the water. In this article we look at the areas of tide you need to know about without having to look it up in a book. Causes of tides To understand tide is convenient to imagine the earth with an envelope of water all around it, spinning once every 24 hours on its north-south axis with the moon on a line parallel to the equator. Moon Gravity A B Earth Ocean C The tides are primarily caused by the gravitational attraction of the moon. Simplifying a bit, at point A the gravitational pull is the strongest causing a high tide, point B experiences a medium pull towards the moon, while point C has the weakest pull causing a second high tide. Because the earth spins once every 24 hours, at any location on its surface there are two high tides and two low tides a day. There are approximately six hours between high tide and low tide. One way of predicting the approximate time of high tide is to add 50 minutes to the high tide of the previous day. The sun has a similar but weaker gravitational effect on the tides. On average this is about 40 percent of that of the moon. -

Issue 1, Summer 1984, Page 6

Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 6: “The Aleut Baidarka” by George Dyson: History, Aleut, Baidarka Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 10: “Anatomy of a Baidarka” by David Zimmerly: History, Baidarka, Line drawing, Aleut Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 13: “Confessions of a Hedonist” by John Ince: Bathing, Beach tubs Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 14: “ Coastal Rewards” by Lee Moyer: Environment, Marine mammals, observation of, Food, Foraging, Low impact Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 16: “Taking Aim” Environment, British Columbia, Logging Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 20: “A Sobering Lesson” by Derek Hutchinson: Safety, Accident report, Britain Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 22: “What If?” by Matt Broze: Safety, Accident report, New Hampshire, British Columbia Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 26: “Northwest Passage” Journey, Northwest Territories Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 34: “ Baby Gray” by Art Hohl: Environment, Safety, Accident report, Marine mammals, Whale collision with kayak Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 37: “San Juans” by Steven Olsen: Destination, Washington, San Juan Islands Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 39: “Getting Started” by David Burch: Navigation, Basic equipment Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 41: “Tendonitis” by Rob Lloyd: Health, Tendonitis, Symptoms and treatment Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 45: “To Feather or Not to Feather” by John Dowd: Technique, Feathering paddles Issue 1, Summer 1984, page 46: “New on the Market” Equipment, Paddle float review Issue 2, Fall 1984, page 6: “Of Baidarkas, Whales and Poison Tipped Harpoons” by George Dyson: History, Aleut, Baidarkas -

WATER ENVIRONMENT A3d.1 INTRODUCTION

Offshore Energy SEA APPENDIX 3d - WATER ENVIRONMENT A3d.1 INTRODUCTION A number of aspects of the water environment are reviewed below in a UK context, and for individual Regional Seas: • The major water masses and residual circulation patterns in UK seas • Density stratification (influenced principally by temperature and salinity) and frontal zones between different water masses – these represent potentially important areas for biological productivity • Tidal flows • Overall patterns of temperature and salinity • Wave climate • Ambient noise Recent assessments of changes in hydrographic conditions are summarised, based mainly on reports by DEFRA (2004a, b) and MCCIP (2007). Overall, significant anomalies and changes have been noted in sea surface temperature (SST), thermal stratification, circulation patterns, wave climate, pH and sea level – many appear to be correlated to atmospheric climate variability as described by the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Larger- scale trends and process changes have also been noted in the North Atlantic (e.g. in the strength of the Gulf Stream and Atlantic Heat Conveyor (more properly characterised as the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC), or the Atlantic Thermohaline circulation (THC) e.g. Trumper 2005), Northern Hemisphere (Weijerman et al. 2005) and globally (IPCC 2007a). There are varying degrees of confidence in the interpretation of observed data and prediction of future trends. Finally, the specific environmental issue of eutrophication is summarised. This is an area of concern in specific geographical areas, notably the southern North Sea and various coastal and estuarine locations. A3d.2 UK CONTEXT The history of broadscale studies of North Sea circulation and hydrographic patterns (e.g. temperature and salinity distribution) was briefly reviewed in SEA 2. -

A1d Water Environment

Offshore Energy SEA 3: Appendix 1 Environmental Baseline Appendix 1D: Water Environment A1d.1 Introduction A number of aspects of the water environment are reviewed below in a UK context, and for individual Regional Seas: • The major water masses and residual circulation patterns • Density stratification (influenced principally by temperature and salinity) and frontal zones between different water masses • Tidal flows • Tidal range • Overall patterns of temperature and salinity • Wave climate • Internal waves • Water Framework Directive ecological status of coastal and estuarine water bodies • Eutrophication • Ambient noise Recent assessments of changes in hydrographic conditions are summarised, based mainly on reports by Defra (2010a, b) and MCCIP (2013) but incorporating a range of other grey and peer reviewed literature sources. Overall, significant anomalies and changes have been noted in sea surface temperature (SST), thermal stratification, circulation patterns, wave climate, pH and sea level – many appear to be correlated to atmospheric climate variability as described by the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Larger-scale trends and process changes have also been noted in the North Atlantic (e.g. in the strength of the Gulf Stream and Atlantic Heat Conveyor (more properly characterised as the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC), or the Atlantic Thermohaline circulation (THC), northern hemisphere and globally. There are varying degrees of confidence in the interpretation of observed data and prediction of future trends. A1d.2 UK context There have been a number of information gathering and assessment initiatives which provide significant information on the current state of the UK and neighbouring seas, and the activities which affect them. These include both UK wide overview programmes and longer term specific monitoring and measuring studies. -

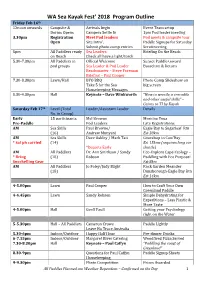

WA Sea Kayak Fest' 2018 Program Version 16

WA Sea Kayak Fest’ 2018 Program Outline Friday Feb 16th 12noon onwards Campsite & Arrivals begin Event Team setup Dorms Opens Campers Settle In 1pm Pod leader meeting 3.30pm Registration Meet Pod leaders Pod meets & campsite tour Open Site Intro’, Paddle Signups for Saturday Submit photo comp entries Scrutineering 5pm All Paddlers ready Sea Leaders Briefing On the Beach on Beach Check all have a light/torch 5.30-7.30pm All Paddlers in Official Welcome Sunset Paddle toward pod groups Sea Leader & Pod Leader Busselton & Return Beachmaster – Steve Foreman Briefing – Paul Cooper 7.30-8.30pm Lawn/Hall BYO BBQ Photo Comp Slideshow on Take 5 for the Sea big screen Housekeeping Messages 8.30-9.30pm Hall Keynote – Dave Winkworth “How to wrestle a crocodile and other useful skills” – Cairns to TI by Kayak Saturday Feb 17th Level (Total Leader/Assistant Leader Details No. in Group) Early 15 participants Mel Browne Morning Yoga Pre-Paddle Pod Leaders Late Registrations AM Sea Skills Paul Browne/ Eagle Bay to Sugarloaf Rtn (16) Andrew Munyard Est 30km AM Sea Skills Dave Oakley / Mark Tait Gnarabup to Cow’Bay * Sat ph carried (14) Est 15kms (requires long car *Departs Early shuttle) AM All Paddlers Dr. Ann Smithson / Sandy Eco-Explore Cape Ecology – * Bring (18) Robson Paddling with Eco Purpose! Snorkelling Gear Est 8km AM All Paddlers Jo Foley/Judy Blight Rock Garden Meander (18) Dunsborough-Eagle Bay Rtn Est 14km 4-5.00pm Lawn Paul Cooper How to Craft Your Own Greenland Paddle 4-4.45pm Lawn Sandy Robson Simple Dehydrating for Expeditions – Less Plastic -

Merging Velocity Measurements and Modeling to Improve Understanding of Tidal Stream Resource in Alderney Race

Merging velocity measurements and modeling to improve understanding of tidal stream resource in Alderney Race. Maxime Thiébaut, Alexei Sentchev, Pascal Bailly Du Bois To cite this version: Maxime Thiébaut, Alexei Sentchev, Pascal Bailly Du Bois. Merging velocity measurements and modeling to improve understanding of tidal stream resource in Alderney Race.. Energy, Elsevier, 2019, 178, pp.460-470. 10.1016/j.energy.2019.04.171. hal-02336285 HAL Id: hal-02336285 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02336285 Submitted on 28 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Merging velocity measurements and modeling to improve understanding of tidal stream resource in Alderney Race Maxime Thiébaut1,2 , Alexei Sentchev*1 and Pascal Bailly du Bois3 (1) Univ. Littoral Côte d’Opale, Univ. Lille, CNRS, UMR 8187, LOG, Laboratoire d’Océanologie et de Géosciences, Wimereux, France (2) France Énergies Marines, Technopôle Brest-Iroise, Batîment Cap Océan, 525 Avenue de Rochon, Plouzané, France (3) IRSN/DEI/SECRE/LRC, Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire, Direction de l Environnement et de l Intervention, Laboratoire de Radioécologie de Cherbourg Octeville, France (*) Corresponding author: [email protected] Phone : +33 3 21 99 64 17 Fax : + 33 3 21 99 64 01 Abstract Tidal circulation and tidal stream resource in Aldemey Race (Raz Blanchard) were assessed by using a towed acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP) system and tidal modeling. -

Maine Guide Training

Maine Guide Training 2021 History of Maine Guides ● First hired guides in Maine were Abenaki people who led European explorers, military officials, traders, priests and lumbermen. ● Guiding industry emerged in late 1900s as people in more urban and industrialized regions sought wilderness for recreation ● Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby was first guide licensed in 1897; 1700 others were licensed that year. Maine’s Legal Definition of “Guide” Any person who receives any form of remuneration for his services in accompanying or assisting any person in the fields, forests or on the waters or ice within the jurisdiction of the State while hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, snowmobiling or camping at a primitive camping area. Sea Kayaking Guide Specialization Guides can lead paddlesports trips on the State's territorial seas and tributaries of the State up to the head of tide and out to the three mile limit. This classification includes overnight camping trips in conjunction with those sea-kayaking and paddlesports. Testing Process 1. Criminal Background Check 2. Oral Examination ■ Chart and compass work ■ Catastrophic scenario 3. Written Examination (minimum score of 70 to pass) What Maine Sea Kayak Guides CAn Do ● Lead commercial sea kayaking and SUP trips on Maine’s coastal waters ● Lead overnight camping trips associated with these trips (new as of 2005) ● Lead trips with up to 12 people per guide What Sea Kayak Guides CAN’T Do ● Lead paddling trips on inland waters (by kayak, canoe, SUP or raft) ● Take clients fishing or hunting ● Lead trips that require another type of guide license What are the qualities that you most appreciated in guides you’ve encountered? ● Wilderness Guide Association’s Definition of a Guide A trained and experienced professional with a high level of nature awareness. -

The Long Reach of the Past

SeaTrek The Long Reach of the Past www.vskc.org.au Winter 2016 Issue 86 The VSKC Bass Strait, and take their kayaks its annual general meeting held to remote and interesting areas. as part of a weekend of activities The Victorian Sea Kayak Club Equally, we all love relaxing short on and off the water, with was formed in 1979, aimed at trips in our local waters, with informative training sessions and bringing together sea kayakers in plenty of time to socialise. presentations from interesting our part of the world, creating We welcome new members and speakers. We run a range of club opportunities to meet and encourage a culture in which trips throughout the year for all organise trips, and to promote members help each other with levels of ability, helping members the interests of sea kayakers. skills, gear, safety, trip to improve their proficiency and Club members have done some information and organisation. take part in trip leadership. We marvellous and sometimes very The club runs training courses keep in touch through this challenging trips by sea kayak and has a grading system, website, email news, and our club around our nearby coasts of although training is not aimed at magazine Sea Trek. Victoria and Tasmania and absolute novices. New members For more information read go to further afield. Our founding are expected know something of the Docs and Downloads link members made the first sea sea kayaking, have access to a from the Web page, and kayak circumnavigation of kayak, and be ready to explore download our Operating Tasmania and the first south to the marvellous opportunities Principles and Membership north crossing of Bass Strait. -

Studies of Marine Mammals in Welsh High Tidal Waters

Assessment of Risk to Marine Mammals from Underwater Marine Renewable Devices in Welsh waters Phase 2 - Studies of Marine Mammals in Welsh High Tidal Waters On Behalf of Welsh Assembly Government Date: 28th March 2011 Our Ref: JER3688 RPS Conrad House Beaufort Square Chepstow Monmouthshire NP16 5EP Tel: (0)1291 621 821 Fax: (0)1291 627 827 Email: [email protected] This document is Printed on FSC certified, 100% post-consumer recycled paper, bleached using an elemental chlorine- free process. JER3688 Welsh Assembly Government Planning & Development th 28 March 2011 IMS J 0014v0 Studies of Marine Mammals in Welsh High Tidal Waters Quality Management Prepared by: Jonathan Gordon (Ecologic UK Ltd.) Prepared by: Dave Thompson (SMRU) Prepared by: Russell Leaper (University of Aberdeen) Prepared by: Douglas Gillespie (SMRU) Prepared by: Chris Pierpoint (Eurydice) Prepared by: Susannah Calderan Prepared by: Jamie Macaulay (Ecologic UK Ltd.) Prepared by: Thomas Gordon (Vanishing Point) Authorised by: Nicola Simpson Date: 28th March 2011 Revision: 5 Project Number: JER3688 Document Reference: JER3688R110408JG Phase 2 - Studies of Marine Mammals in Welsh High Tidal Energy Waters v5.doc Document File Path: O:\JER3688 - Marine renewable Strategy for Wales\STAGE 2\Project File\Task 1&2 Marine Mammals Collision Risk\JER3688R110408JG Phase 2 - Studies of Marine Mammals in Welsh High Tidal Energy Waters v5.doc JER3688 Welsh Assembly Government Planning & Development i 28th March 2011 Studies of Marine Mammals in Welsh High Tidal Waters DISCLAIMER The -

Oceans 11 Teaching Resources Vol 1

Oceans 11 A Teaching Resource Volume 1 1 Foreword Oceans 11 curriculum was developed by the Nova Scotia Department of Education as part of a joint project with the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans. This curriculum reflects the framework described in Foundation for the Atlantic Canada Science Curriculum. Oceans 11 satisfies the second science credit requirement for high school graduation. Oceans 11 includes the following modules: Structure and Motion, Marine Biome, Coastal Zone, Aquaculture, and Fisheries. Oceans 11: A Teaching Resource, Volume 1 is intended to complement the curriculum guide, Oceans 11. The sample activities in this resource address the outcomes described in Oceans 11 for the three compulsory modules: Structure and Motion, Marine Biome, and Coastal Zone. Oceans 11: A Teaching Resource, Volume 2 is intended to complement Oceans 11. The sample activities in it address the outcomes for the modules Aquaculture and Fisheries. Teachers may choose to do one of these units or to divide their class into groups that focus on a unit. 2 Contents Structure and Motion Introduction Materials The Ocean Industry in Nova Scotia The Ocean Industry in Nova Scotia, Teacher Notes When Humans and the Ocean Meet When Humans and the Ocean Meet, Teacher Notes Bodies of Water Bodies of Water, Teacher Notes Bathymetric Profile Sketching Bathymetric Profile Sketching, Teacher Notes Water Facts Water Facts, Teacher Notes Comparing Densities of Fresh Water and Seawater Comparing Densities of Fresh Water and Seawater, Teacher Notes The Effects -

Enon Valdez Oil Spill Restoration Project Final Report Site Specific

Enon Valdez Oil Spill Restoration Project Final Report Site Specific Archaeological Restoration at SEW-440 and SEW-488 Restoration Project 95007B Final Report Linda Finn Yarborough United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Chugach National Forest 3301 C St., Suite 300 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 October 1997 Site Specific Archaeological Restoration at SEW440 and SEW488 Restoration Project 95007B Final Report Siw:The project effort was initiated under Restoration Project 94007B.An annual progress report was issued in January, 1995 by Yarborough, L., under the title Restoration ~ -1995. Theproject continued under Restoration Project 95007B, the subject of annual this report. A second progress report was prepared in September 1995 by Yarborough, L., under the title 1s Reuort. Seutember 1995. FY 95 wasthe last field season for this project. Data analysis and project report preparation took place in FY 96 and FY97.Papers were prepared for presentation and peer reviewed publication, and results were presented to the public in FY 97. Abstract: Project 94007 provided for restoration of two archaeological sites damaged during the Exxon Vuldez Oil Spill and its subsequent cleanup program. Test excavations were carried out at both SEW-440 and SEW-488 during 1994. Analysis and completion of excavations at SEW-488 took place in 1995. Analysis continued in 1996 and 1997. Each site was assessed in the field and mapped prior to testing. Data recovery work yielded both environmental and cultural information. Both sites appear to have been intermittently occupied, SEW-440 over a period of almost 2000 years, and SEW-488 for up to 3000 years. Artifact and zooarchaeological analyses resulted in information on prehistoric technology, subsistence, seasonality and site use.